Since December 8, 2022, nationwide protests have erupted in Peru after former president José Pedro Castillo Terrones (hereafter, Castillo) was impeached by Congress and detained by police. While protesters strongly demand Castillo’s release and new elections to choose a president, according to Amnesty International, as of February 2023 at least 60 people had died in connection with the protests, and it condemns the government’s violent crackdown as a humanitarian issue.

Behind the current protests lie not only the former president’s arrest but also Peru’s social and political problems. This article takes a closer look at that background.

Scenes from a protest march in the capital (Photo: Mayimbú / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

Peru’s political system

First, let us look at Peru’s political history. Peru is a country in Latin America with a population of about 33,000,000. It is believed that civilization existed more than 10,000 years ago, and amid the rise and fall of many cultures, in the 11th century the unprecedentedly large Inca Empire was established. By 1500, the Inca Empire had expanded its power, absorbing other civilizations, from what is now Ecuador in the north to as far south as Santiago, the capital of present-day Chile.

However, in 1532 the Inca Empire was conquered by invading forces from Spain. Spain colonized the region, and many settlers moved in. The Indigenous peoples living in what is now Peru saw their populations plummet due to diseases brought from abroad. Although the country gained independence from Spain in 1821, the political and economic structures dominated by a small Spanish-descended elite did not change, and Indigenous peoples continued to be oppressed. Power within the government remained fragmented, and even after independence, instability such as conflicts between former military leaders from the independence movement and conservative economic elites persisted. Even so, from around the 1840s the country also showed signs of growth, including the beginnings of modernization through the development of guano, used as a raw material for fertilizer and gunpowder.

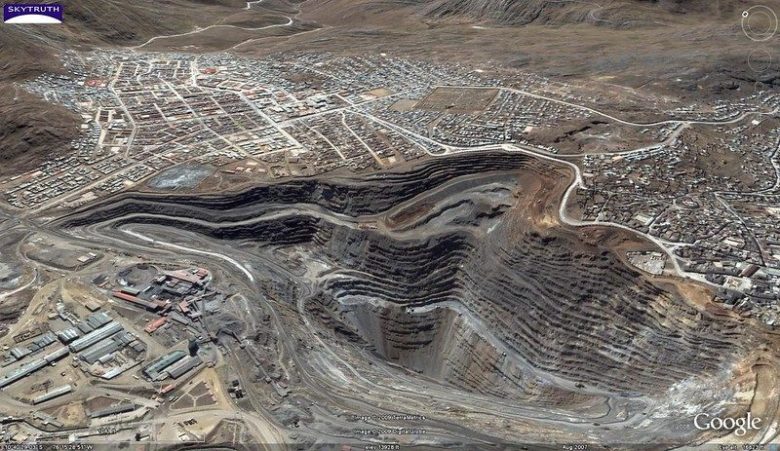

From 1879 an armed conflict with neighboring Chile broke out over mineral resources. As a result of this war, Peru lost sovereignty over resource-rich Tarapacá, which stripped away a major economic foundation. In response, to rebuild the nation, the government in the early 20th century expanded fiscal spending on public works financed by U.S. capital. Around the same time, U.S. international oil companies acquired oil fields in Peru, and from 1908 through the 1930s the Peruvian regime increasingly relied on foreign investment and built an authoritarian political system. From this period, Peru pursued growth with an economic structure based on exporting domestic products such as oil, copper, and rubber.

Zinc, silver, and lead mines in Peru (Photo: SkyTruth (Google Earth image) / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Even as the economy expanded, the gap between urban and rural areas did not narrow. The structure in which elites—descendants of settlers—forced Indigenous people to work as serfs on plantations remained, and Indigenous people and peasants had difficulty accessing education and health care. In 1969, the then left-wing government implemented land reform to redistribute land and enacted policies such as dispatching government teachers to communities that established school buildings, but protections for Indigenous rights and rural infrastructure remained insufficient. Moreover, voting rights for illiterate people were recognized only ten years after land reform, and up to that point Indigenous people and peasants—among whom literacy was not widespread—were excluded from elections.

In the 1980s, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry advanced neoliberal policies, but due to issues such as reduced fishery production from natural disasters like El Niño (※1) and global price declines, Peru’s economic situation worsened. This hit people’s livelihoods hard, with rising unemployment, and the poor were forced into even harsher conditions. Capitalizing on this social discontent, an anti-government group called the Shining Path (Communist Party of Peru) emerged in rural areas. They carried out assassinations and acts of terror, plunging the country into turmoil.

In the 1990s, Alberto Ken’ya Fujimori Inomoto (hereafter, Fujimori) was elected president. While he implemented policies such as fiscal austerity, in 1992 he dissolved Congress and suspended the constitution, building a strong dictatorship. During this roughly 10-year regime, there were cases of indiscriminate massacres of people deemed “terror suspects,” and Fujimori was found responsible for ordering them; in 2009 he was handed a 25-year prison sentence.

Even after Fujimori resigned, political instability continued, with 7 presidents serving in the 6 years from 2016 to 2022.

The Castillo administration

Pedro Castillo, who won the election in July 2021 and became president, was an anomaly in Peru’s political history. He was only the second president since 1956 not born in urban Lima, and, as a peasant by origin, the first in history. Until then, the presidency was held mostly by elites such as descendants of settlers, and people living in rural Indigenous communities had been economically and politically excluded. Even today, many rural areas remain impoverished, and facilities such as hospitals and schools—basic infrastructure—are often insufficient. In response, as the first left-wing government in decades, Castillo pledged to expand spending on social protections like health and education to reduce the extreme disparities between rural areas and the cities, earning strong support from rural communities.

Castillo delivering a speech (Photo: OEA-OAS / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Castillo also signaled a shift in policy on Peru’s mineral resources. Minerals still have a major impact in Peru’s resource-dependent economy, but most of the profits flow to foreign firms. Companies such as the world’s three largest mining firms—BHP Group, Rio Tinto, and Glencore—and oil major Shell have invested heavily in Peru’s mining sector. Castillo argued that such foreign corporations were “plundering” the country and emphasized that the bulk of profits from domestic natural resources should be used for Peru. To that end, he planned to develop domestic industry by improving gas infrastructure and expanding domestic demand.

However, when he took office, only about one-third of the legislature supported him, with the rest dominated by elite, conservative right-wing parties (※2). These lawmakers actively blocked Castillo’s agenda, making it difficult to implement the policies described above. Congress also pursued corruption allegations against him; as of February 2023 there were 6 investigations underway. Castillo denied the accusations, asserting that right-wing forces controlled state institutions such as the prosecutor’s office and that he had been under constant attack politically. In his first year in office he survived two previous impeachment attempts by Congress and was forced to undertake four cabinet reshuffles. It is also said that he faced political pressure from the right through smear campaigns by mainstream media seen as speaking for the elite.

But the instability of his administration was not only due to opposition forces. The fact that Castillo had no prior political experience before becoming president is also seen as a factor. For example, he called for the nationalization of the mining sector and for a constituent assembly to amend the constitution—pledges he had made during the campaign. Yet he showed little willingness to compromise, attempting to introduce policies that would bring major changes without first consolidating a political base.

Castillo (center) attending a ceremony (Photo: Ministerio de Defensa del Perú / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The “coup” and the ensuing protests

On December 1, 2022, Peru’s Congress initiated a third round of impeachment proceedings against Castillo over multiple corruption allegations. The previous two attempts had failed for lack of votes, and this one was likely to fail as well. However, the situation changed dramatically when Castillo, in a televised address to the nation, declared that he would temporarily close Congress and establish a provisional government to draft a new constitution (※3). Cabinet ministers did not follow his lead; almost all immediately resigned after the announcement and condemned his decision. Given the precedent that Fujimori’s 1992 dissolution of Congress paved the way for his dictatorship, the Constitutional Court claimed it had averted Castillo’s “coup.” Similarly, Peru’s judiciary and military deemed the decision unconstitutional.

Citing Article 113 of the Peruvian Constitution—which allows the president to be removed for “permanent moral incapacity” with a two-thirds vote of lawmakers—on December 8, 2022 Congress removed Castillo from office, and the judiciary charged him with “rebellion,” after which police moved to arrest him. In response to the congressional decision, Castillo sought asylum at the Mexican Embassy, but he was detained by police en route and imprisoned without judicial proceedings. To complete Castillo’s term through 2026, Vice President Dina Ercilia Boluarte Zegarra (hereafter, Boluarte) was sworn in as president, and Congress formed a new cabinet, but this transition did not involve democratic electoral procedures and was decided entirely within Congress.

Boluarte after becoming president (Photo: Presidencia Perú / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

In response to these developments, many people across Peru expressed full support for Castillo and launched protests nationwide. Arguing that he was the victim of a congressional “coup,” they demanded Boluarte’s resignation and early elections, blocking major highways and marching in Lima.

However, the government’s repression of demonstrators was severe. In 2022, in the three weeks after Castillo was removed, there were reported to be 500 injuries and 26 deaths related to the protests. Attacks on protesters—and at times on civilians unconnected to the demonstrations—were reported, and the government’s response caused ripples even within Boluarte’s cabinet, with two ministers resigning because “the death of our compatriots cannot be justified.” Although Boluarte, four days after taking office, declared a state of emergency in some regions, the protests did not subside, and she later declared a nationwide state of emergency.

At the same time, Boluarte called for a truce from protesters and appealed for peace. In response to demands for early elections, she proposed as a compromise to shorten by 2 years the term that Castillo was originally set to complete.

International responses to Peru

Countries’ reactions to Peru’s situation have been divided. Among neighboring Latin American nations, at least 14 countries, including Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina, supported Castillo and even refused to recognize the current government. Furthermore, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, and Bolivia stated in a joint declaration supporting Castillo that “from the day he took office, Castillo was subjected to anti-democratic harassment by Congress.” Indeed, there was an incident in which Peru’s Congress refused to allow Castillo to attend an international conference he was supposed to attend as president. The confrontation between Congress and Castillo was thus clear on the international stage as well.

These moves by Latin American countries are seen as rooted in the regional divide between right- and left-leaning governments. In Latin America, right-wing governments are generally pro-U.S. and adopt many neoliberal policies, whereas left-wing governments often espouse anti-imperialism (※3) and put forward measures to expand social welfare. The trend of more leftist governments is known as the “pink tide” (※4), and this trend has reemerged since around 2022. The countries that backed Castillo may have seen significance in asserting leftist solidarity in a region where the right–left divide is in flux.

By contrast, the United States supports the current government. After Castillo announced the dissolution of Congress, U.S. Ambassador to Peru Lisa Kenna posted a tweet stating that his actions were unconstitutional and that the U.S. firmly rejected such moves. Immediately after the change of government in Peru, the U.S. State Department expressed support for the Boluarte administration.

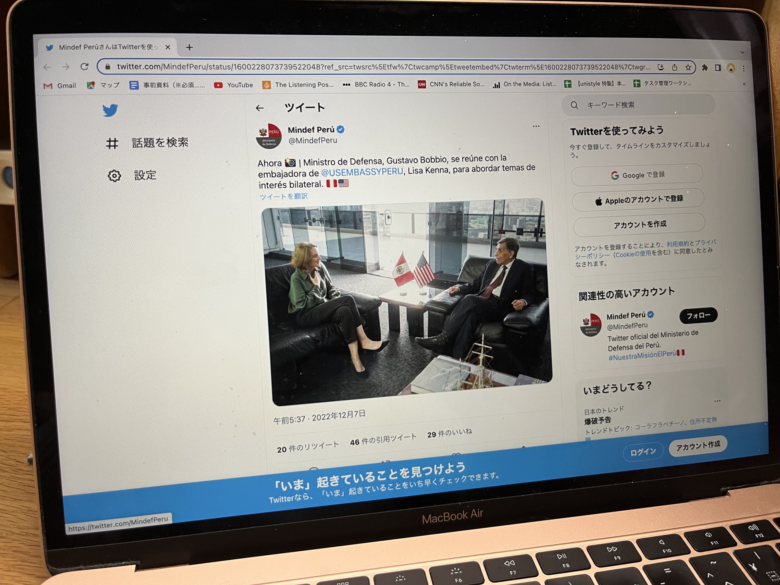

These U.S. moves have prompted speculation about Washington’s motives. Kenna is a former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) official, and it was reported that she met with Peru’s defense minister the day before Castillo’s arrest. The next day, that minister ordered the military to defy the sitting president, Castillo. This has fueled suggestions of U.S. involvement in Peru’s regime change.

Tweet by Peru’s Ministry of Defense about the meeting between the U.S. ambassador and Peru’s defense minister (Photo: Maika Ito)

Even after the transition to the Boluarte government, Kenna has continued to meet regularly with top officials, and on January 18, 2023 it was announced that she discussed investment in Peru’s energy sector and the expansion of industrial development with the energy and mines minister. Unlike Castillo, who sought to nationalize mining operations, the current government is actively welcoming foreign investment and is seen as aligned with U.S. interests in expanding access to Peru’s resources.

Outlook

As of March 2023, protests were continuing but diminishing. For example, with roads reopened after earlier blockades by demonstrators, Peru’s copper exports, which had been stagnating, were expected to normalize. At the same time, Peru’s attorney general announced that Boluarte had been questioned about the crackdown that led to protesters’ deaths. She was summoned because several members of the current government were reportedly being considered for indictment on murder charges. She made no comment to reporters. According to a survey by the Institute of Peruvian Studies (IEP), 75% of respondents did not support Boluarte, and 90% did not support Congress. Taken together, it is hard to say the Boluarte administration is on a stable trajectory.

Many are raising concerns about the rural–urban divide underlying this “coup” and a political system in which the right controls state institutions. Yet without compromise and a willingness to cede power from the small domestic elite, a fundamental resolution may be out of reach. We will need to keep watching to see whether the Peruvian government adopts such an attitude.

※1 El Niño is a phenomenon in which sea surface temperatures in normally cold-water regions become higher than average due to warm water flowing in from the equatorial area.

※2 There was also a systemic political problem in Peru’s Congress, which has more than 10 parties: party strength tends to be diluted, making it difficult to build a strong support base.

※3 According to Castillo, his move was based on Article 134 of the Peruvian Constitution, which allows the president to dissolve Congress if it twice refuses confidence, but this action is widely viewed as not meeting the constitutional conditions.

※4 Anti-imperialism refers to opposing imperialism, in which one country exploits another politically and economically for its own benefit. In this article, anti-imperialism refers to opposition to U.S. intervention in Latin America.

※5 “Pink tide: The term contrasts with ‘red tide,’ which denotes the spread of communism. In Latin America, the shift toward left-leaning governments did not go as far as full communism; because these governments are socialist to a lesser degree, the lighter color pink—rather than red—is used, hence ‘pink tide.’”

Writer: Maika Ito

Graphics: Yudai Sekiguchi

0 Comments