In recent years, growing attention has been paid to the conditions under which fast fashion and sports brand products sold around the world are manufactured and by whom before they reach consumers. In Asia, apparel production is thriving in countries such as China and Vietnam, but companies are also expanding into Cambodia and Bangladesh in search of lower labor costs and looser labor regulations.

In January 2023, Cambodia raised the minimum wage in the textile sector to 200 US dollars per month. This was an increase of 6 US dollars from the previous monthly wage of 194 US dollars. Will this improve workers’ lives? This article looks at the light and shadows of Cambodia’s textile industry.

“MADE IN CAMBODIA” goods being packed and shipped (Photo: U.S. Embassy Phnom Penh / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

目次

Cambodia, a textile powerhouse

Cambodia is a country in Southeast Asia with a population of about 17 million. From 2010 until the COVID-19 pandemic, its gross domestic product (GDP) grew by around 7% annually, making it one of the countries that have seen remarkable economic development in recent years. For Cambodia’s history and political system, see GNV’s previous article, “Cambodia: A Hotbed of Illegal Trade.”

Next, let’s look at the structure of its industries. As of 2021, the composition of GDP was 37% manufacturing, 34% services, and 23% agriculture. Within manufacturing, the mainstay is the textile industry, which is said to generate more than 1/3 of Cambodia’s overall GDP. Much of this output is produced for export. As of 2021, exports of clothing and footwear totaled about 10 billion US dollars, accounting for about 60% of all exports. More than 1 million people are involved in the textile industry, giving it a major impact on the domestic economy. Another feature is that about 90% of these workers are women.

There are mainly three reasons why the textile industry has developed in Cambodia: special arrangements with the United States and the European Union (EU), low-cost domestic labor, and government policy. Let’s look at each in detail. First, the background to the special arrangements with the United States and the European Union (EU) goes back to 1974. That year, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Council approved the Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA), which established quotas to regulate the influx of low-cost textile products produced in low-income countries into importing countries. While textile exporters in Asia, such as China, were heavily restricted by quotas, Cambodia was not subject to quotas for the United States and the EU. In other words, compared with other countries, Cambodia could export a relatively large volume of clothing to Western countries, which are major consumer markets.

Second, the availability of cheap domestic labor meant that wages could be kept lower than producing in high-income countries, contributing to the development of Cambodia’s textile industry. In fact, as of 2015, the labor cost to produce one cotton shirt was roughly 7 US dollars in the United States, compared with 0.33 US dollars in Cambodia—less than 1/20. Because of these factors, since the mid-1990s Cambodia has been chosen as a production site for textiles, and many foreign-owned companies have moved in. Although the MFA was abolished in 2004, quota restrictions on China remained in many countries, creating a favorable environment for Cambodia’s textile industry to continue to grow. In 2008, quotas on China were lifted; however, wage increases and labor shortages occurred in China and Vietnam around this time, bringing additional tailwinds as some orders flowed to Cambodia.

Third, in addition to these international conditions, government policies also contributed to the further development of the textile industry. The government actively courted foreign companies and revised the tax system to favor the textile sector. In this way, an industry that grew through both domestic and international factors has driven Cambodia’s economic growth.

Given this background, looking at the top 10 export destinations for Cambodia’s textiles as of 2020, the United States accounts for about 33%, EU countries for about 28%, and Japan for about 10%. This export destination mix is distinctive compared with other textile-exporting countries. For example, in 2020 Vietnam’s textile export destinations—the United States, Japan, China, and South Korea—accounted for over 70% of the total, and the share going to the EU is not as large as in Cambodia.

Women receiving vocational training (Photo: International Labor Organization / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The dark side of Cambodia’s textile industry

As noted above, measured in terms of GDP, the textile industry has greatly contributed to Cambodia’s economic development. However, GDP is merely an indicator of the size of the economy and does not show how the value added is distributed. In other words, if the profits generated through the textile industry are concentrated in the hands of government officials and management/shareholders—the so-called elite—it may not translate into “development” for the majority of citizens, including workers. Thus, national development via the textile industry is not necessarily positive for workers. In fact, since the industry developed in Cambodia, numerous negative reports have emerged—up to the present day—of low wages and poor working conditions. Of course, there are some mechanisms to protect workers’ rights. Cambodia enacted a Labor Law in 1997 that sets out labor relations and working conditions. In 2001, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) established Better Factories Cambodia (BFC), an organization expected to monitor factories from a third-party standpoint. Even so, what can only be called sweatshops—situations in which workers are employed at low wages and under harsh conditions—persist in Cambodia’s textile industry. Below, we examine the current situation from the perspectives of wages, working conditions, and work environments.

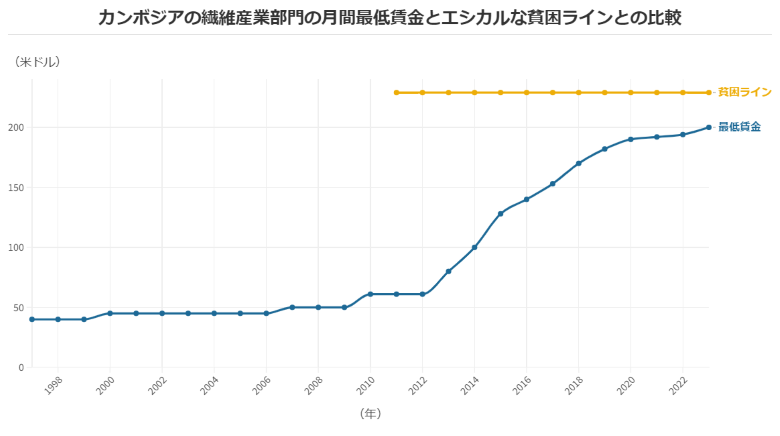

The foremost problem facing Cambodia’s textile industry is extremely low pay. Since the minimum wage was first set in 1997, the monthly minimum wage in the textile sector has been gradually improved from 40 US dollars, and in 2022 it was decided to raise it to 200 US dollars per month. However, as the graph below shows, this remains low relative to the ethical poverty line (Note 1) of about 229 US dollars per month. Even when working full-time and long hours in such factories, workers cannot support their families—in fact, the workers themselves remain in poverty. As a result, income from the textile industry plays only a supplementary role in household budgets, and about 90% of those employed are women (Note 2).

Violations of workers’ rights arise not only from low wages but also from poor working conditions and environments. Regarding working conditions, 2014 data found violations of overtime regulations in 94% of factories monitored by BFC. Furthermore, as of 2015, forced long hours and denial of breaks or sick leave were reported. In fact, in 2017, workers in the textile industry reportedly worked on average around 220 hours per month. The Labor Law permits a maximum of 192 hours per month, meaning actual hours far exceed the legal limit.

From the perspective of the work environment, incidents have shown that safety and security at the workplace have not been adequately ensured. In 2013, in apparel factories supplying brands such as Adidas, there were three mass fainting incidents in quick succession, likely caused by inadequate indoor ventilation, with dozens of workers collapsing at once. 2014 data also showed temperature-control violations in 64% of factories monitored by BFC. As of 2015, there were reports of child labor, maternity harassment, and sexual harassment as well, and examples of poor working environments are too numerous to list. Regarding child labor, a 2018 BFC survey reported a reduction from 74 cases in 2014 to 10, but in reality child labor likely persists in subcontracted factories or homes not covered by BFC monitoring, meaning reported cases are probably only part of the picture.

Behind these problems lie the complexity and opacity of textile supply chains. Not all clothing manufactured in Cambodia is made in factories directly run by foreign companies. Large factories and vendors producing for export often seek even cheaper labor by subcontracting to smaller factories; subcontractors may then hire other workers by the hour or outsource to home-based workers. As a result, foreign companies and the Ministry of Labor often have limited oversight of actual working conditions, and workers’ rights are neglected. Arguably, foreign companies, in their pursuit of cheap labor, may knowingly turn a blind eye to the realities of subcontracting and outsourcing because they are difficult to fully grasp.

Inside a garment factory in Cambodia (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Mixed progress toward improvement

Is there any movement toward improvement in this situation? It is worth emphasizing that the continuous wage increases since the 2000s were not automatic; they were gradually won by workers who took action despite the risks of dismissal, arrest, and violence. Indeed, since the 2000s, there have been dozens of strikes and demonstrations every year, as many workers resisted existing working conditions and environments. Yet such strikes and demonstrations, though officially recognized as workers’ rights under the Labor Law, have consistently faced repression. At times, 1,000 participants in a strike were fired, or participants were arrested by the authorities. There have even been cases where not only the police but also the national military were deployed against demonstrations. In 2014, soldiers fired rifles at demonstrators supporting a strike, resulting in deaths in a horrific incident. The serious issue here is that this repression has consistently been carried out by the government, which should be protecting workers’ rights.

Repression of efforts to restore workers’ rights is not limited to direct violence but also includes more insidious tactics. For example, officially sanctioned demonstrations and strikes can be applied for and carried out by approved labor unions. However, the Ministry of Labor, which oversees the Labor Law, is believed to deliberately complicate the process of union approval, making official demonstrations and strikes harder to organize. In 2022, Cambodia also introduced an internet censorship system, which likely makes it more difficult to voice dissent and organize gatherings online.

Fundamentally, this persistent repression is tied to the country’s governance structure. Looking at the political system, the government appears more interested in the interests of elites—government officials, management, and shareholders—than in the realities faced by the country’s own workers. Since 1979, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) led by Prime Minister Hun Sen has remained in power. Although Cambodia is nominally a constitutional monarchy, in practice it is effectively ruled by Hun Sen. In the 2017 election, when the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party gained the upper hand, the authorities detained its leader for treason and dissolved the party. The Hun Sen family holds interests in 114 companies across various domestic industries, reflecting a dominant position in the economy. Thus, the current government, clinging to power, seems more concerned with maintaining good relations with foreign and domestic large companies that bring them greater profits than with protecting workers’ rights.

Scenes from a strike in Cambodia (Photo: International Labor Organization / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has dealt a further blow to Cambodia’s textile industry. As demand for clothing in high-income countries shrank, manufacturing orders to Cambodia declined. In some cases, even orders that had already been placed were suddenly canceled, leaving factories with large amounts of unsold inventory. The “inventory” for these factories was not only goods, but also facilities, foreign investors, and the workers in the textile sector who had long contributed greatly to companies and the national economy. Factories that were not paid by foreign brands for canceled orders were forced to dismiss hundreds of workers, halt wage payments, or reduce working hours. As of 2020, more than 110 garment factories had closed and over 50,000 workers lost their jobs, according to one view. In response, unions called on the foreign brands that had placed the orders to pay at least the minimum wage, and it appears that some companies provided compensation.

Cambodia’s path forward

We have shown that Cambodia’s textile industry is rife with problems and that solving them will not be simple. What paths forward are conceivable? Fundamentally, unless the share of apparel prices and revenues going to labor increases—and the so-called “unfair trade” status quo improves—the plight of workers will not be resolved. The fact that the heads of major fashion brands with factories in Cambodia are among the wealthiest people in the world illustrates this imbalance. For example, in 2015 ZARA founder Amancio Ortega ranked No. 1 on the global rich list; in 2022 Nike (NIKE) founder Phil Knight ranked 27th in the world; and Tadashi Yanai, president of UNIQLO (UNIQLO) and holding company Fast Retailing, ranked No. 1 in Japan.

Prime Minister Hun Sen and others displayed on a billboard (Photo: Michael Coghlan / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

At the same time, Cambodia’s economy has grown through courting foreign companies, and the government may intend to enrich the nation and indirectly return benefits to citizens through this. However, the trickle-down theory (Note 3) has been shown not to occur in reality; even when the economy grows, it often merely means more wealth for elites. Given that labor movements are currently being suppressed and the minimum wage demanded by workers has not been achieved, focusing on citizens’ livelihoods should be an urgent priority for the government. Furthermore, this issue is by no means limited to Cambodia’s textile industry. Although there has been slight improvement in the apparel sector, the construction industry remains even more difficult for workers, and the protection of workers’ rights requires improvements across the entire country, not just in specific sectors. In any case, Cambodia needs political and economic activity that truly benefits its citizens.

Note 1: At GNV we adopt the ethical poverty line (US$7.4/day) rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line (US$1.90/day). For details, see the GNV article “How should we read the world’s poverty situation?”

Note 2: In Cambodia, in most households the man is the breadwinner.

Note 3: Trickle down refers to the economic theory that “when the rich become richer, economic activity intensifies, and wealth trickles down to the poor, redistributing benefits.”

Writer: Yosuke Asada

Graphics: Yosuke Asada

就活してて「ブラック企業」とかに敏感になってたけど、カンボジアの現状を見ると日本のブラック企業はそうでもないなと感じてしまうほどだ

自分の服のタグを見返してみます