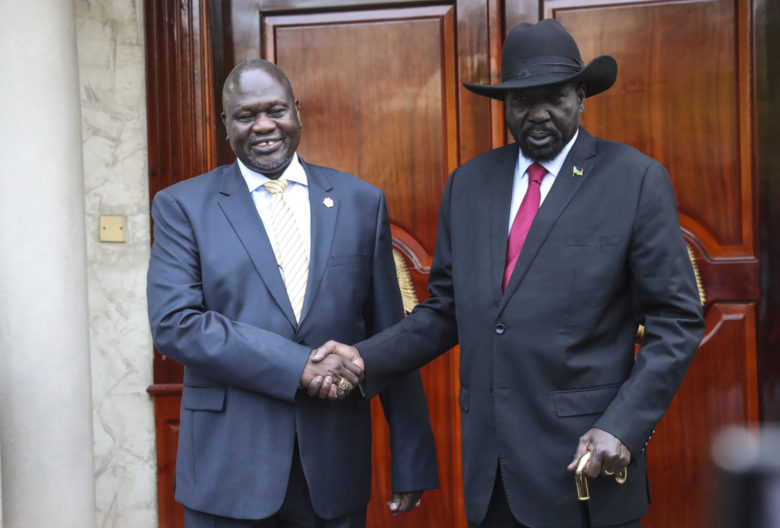

In April 2022 in South Sudan, President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar—who had been rivals until recent years—agreed to unify the commanders of their respective forces, marking a milestone toward peace in the country. This unification had been envisaged under the 2018 peace agreement, yet continued rivalry after the accord stalled progress until it was finally achieved in 2022. Furthermore, in August (8) of the same year, a 2-year extension of the peace deal was decided. The original deadline had been until 2/2023, raising the possibility that many important provisions planned under the accord—such as a presidential election—would expire without being implemented; however, the two sides successfully agreed to extend the deadline.

Thus, while the rapprochement between the president and vice president seemed to be progressing smoothly in 2022, clashes between their camps have still persisted in some areas, and distinct types of conflict have continued at the regional level as well. In addition to these conflicts, civilians across South Sudan are also suffering from widespread flooding and the ensuing food crisis. With a presidential election scheduled for 2024, how will developments unfold as the country moves toward the vote? This article explores these issues.

President Kiir and Vice President Machar clasp hands upon agreeing to unify the forces and other measures (Photo: UNMISS / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

South Sudan’s journey so far

“Sudan” originally refers to the region upstream on the Nile south of Egypt. In ancient times there were the Kingdoms of Kush and Meroe; in the 16th century Islamic states such as the Funj Sultanate and the Sultanate of Darfur emerged. In the 19th century Sudan was invaded and occupied by Egypt, and later became a British colony when Britain colonized Egypt. During this period, Britain favored northern Sudan over the south, sowing the seeds of north–south antagonism.

In 1956, Sudan achieved independence from the United Kingdom. However, conflict between the country’s north and south had raged even before independence, and large-scale north–south wars broke out from 1955 to 1972 and again from 1983 to 2005. In 2005, a Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed between north and south, ending the war. Under the CPA, southern independence would be deferred for 6 years in exchange for the establishment of a regional government with autonomy, and a referendum on independence would be held in 2011—6 years later. As a result of that referendum, South Sudan became independent in 2011, with Kiir as president and Machar as vice president.

Despite independence, the two countries were left with various legacies of the long war and issues such as the concentration of oil resources in South Sudan. The dispute over the Abyei area (Note 1) along the Sudan–South Sudan border has persisted, and its final status remains undecided. In 2011, the United Nations established the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) and the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA). The former protects civilians, monitors and reports on human rights, supports humanitarian aid, and assists implementation of peace agreements, while the latter monitors the border.

Political conflict

Having experienced conflict with Sudan, South Sudan also saw political infighting at home after independence. In December 2013, President Kiir dismissed Vice President Machar, triggering fierce fighting between the Kiir and Machar camps over political power. Although this conflict is considered primarily a struggle for power, ethnic divisions—between Kiir’s Dinka background and Machar’s Nuer background—also played a role. Civilians were targeted, and sexual violence, destruction of property, and looting occurred. In response, the United Nations increased the peacekeeping force it had deployed since 2011 by about 6,000 troops, adding to approximately 7,000 already in-country, to protect civilians. In August 2015, the two sides agreed to reinstate Machar as vice president, offering a glimpse of reconciliation, but fighting reignited in July 2016, after which Machar fled the country.

Peacekeepers newly reinforced to respond to the outbreak of intense conflict (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In June 2018, the two leaders met for the first time in two years and signed a peace agreement; Machar was reinstated as vice president, and a unity government was agreed. In February 2020, that unity government was formally established. It was to be a transitional arrangement through 2023, during which critical steps toward peace—such as drafting a constitution and unifying the armed forces—would be undertaken. Implementation has lagged, however, and fighting still breaks out from time to time. As noted above, unification of the forces was finally implemented in 4/2022, roughly 4 years after the peace accord was signed. A presidential election was initially to be held in early 2023 to end the transitional government, but in 8/2022 it was postponed to 12/2024, extending the transitional government’s tenure by a further 2 years. On the ground, sporadic fighting flared in early 2022 in Upper Nile, Unity, and elsewhere. According to the UN, between February and May 2022, 173 people were killed and about 44,000 were displaced by the violence.

Thus, while the two sides have made some progress toward reconciliation, the recurrence of conflict and delays in implementing the peace accord indicate that many challenges remain.

Regional-level conflicts

Beyond the high-level political power struggle outlined above, multiple conflicts have also erupted at the regional level in South Sudan. These local conflicts are often framed simply as clashes grounded in interethnic identities. While that is sometimes the case, many local conflicts are in fact stoked by elites who instrumentalize ethnic divisions, with elite power struggles lurking in the background. According to Dan Watson, a researcher at the US-based NGO ACLED (Note 2), such conflicts can be understood as a continuum of three tiers: elite-level rivalry, state- or regional-level competition, and ethnicized conflict. Below are concrete examples of such local conflicts.

In Warrap State, there had long been tensions between the Rek Dinka and Luanyjang Dinka. Both groups primarily practice pastoralism, and clashes have involved cattle raiding—targeting what is an essential asset in their livelihoods—and attacks on those protecting the herds. Elites who took advantage of this included Lt. Gen. Aluk Koa and President Kiir, who are political rivals. Koa provided military support to his own Rek Dinka, while Kiir—under the banner of a “civilian disarmament campaign”—backed the Luanyjang Dinka to attack the Rek Dinka. The fighting peaked in 8/2020, leaving 148 people dead.

Dinka herders grazing cattle (Photo: BVA / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

In Jonglei State, the Bor massacre of 1991 (Note 3) sparked enduring tensions among the Dinka, Nuer, and Murle. In 2020 this conflict intensified again, with an alliance of Dinka and Nuer groups and Murle groups engaging in cycles of attack and reprisal. Hidden within this was an elite power struggle—namely, competition within a single organization, the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF). Specifically, the SSPDF Military Intelligence Directorate supported Murle groups, while the SSPDF 8th Division backed Dinka and Nuer groups. With elite involvement, the 2020 fighting escalated into a major conflict in which at least 1,058 people were killed.

The main causes of such elite-level rivalries include widespread corruption within government and the concentration of oil-derived wealth in the hands of those in power—factors that drive struggles over power and resources not only at the national level but also down to the regional level.

In these regional conflicts, ethnic rivalries are intertwined with elite power contests, taking on the character of proxy wars and leading to the increased sophistication of weaponry used and the worsening of harm caused by conflict.

Severe flooding

On top of these conflicts, people in South Sudan are suffering from severe extreme weather—most notably flooding in the northern part of the country. In 2021 alone, devastating floods forced around 500,000 people to flee to the Equatoria region in the south.

South Sudan sits on floodplains along the Nile, with heavy rainfall during the August–October rainy season; seasonal flooding had long occurred. Since around 2019, however, flood severity has increased dramatically. During the 2021 rainy season, the area inundated nationwide reached about 6,000 square kilometers—roughly 6 times larger than in 2018. Normally the ground dries out completely during the dry season from January to March, but the rains in 2021 were so extreme that flooding did not fully recede in the 2022 dry season. When the rains returned in 2022, areas that usually do not flood—such as Western Equatoria—were also hit, and by October of that year the number of people affected nationwide had reached 900,000. One contributing factor appears to be abnormal proliferation of riverine vegetation: years of conflict reduced human activity along riverbanks, allowing vegetation to overgrow, obstruct flows, and cause rivers to overflow. Climate change is also cited: as elsewhere, average temperatures in South Sudan are rising rapidly, and rainfall has increased sharply as well.

People in Unity State affected by flooding (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Because of such severe flooding, some residents of the northern regions have been forced to flee south. However, in the south—where poverty is already widespread and resources are limited—displaced people are not necessarily welcomed. Along the way, there have been incidents of bandit attacks in which cattle were stolen. Even upon reaching their destinations after such harsh journeys, safety is not guaranteed. In the Equatoria region—where many flee—clashes have erupted between newcomers fleeing northern floods and long-term residents. Over the past year, such clashes have led to the deaths of dozens of people. New arrivals often end up competing with long-time farming communities over scarce resources.

In short, South Sudan is facing unprecedented flood damage, and the situation surrounding those forced to flee is dire.

The food crisis

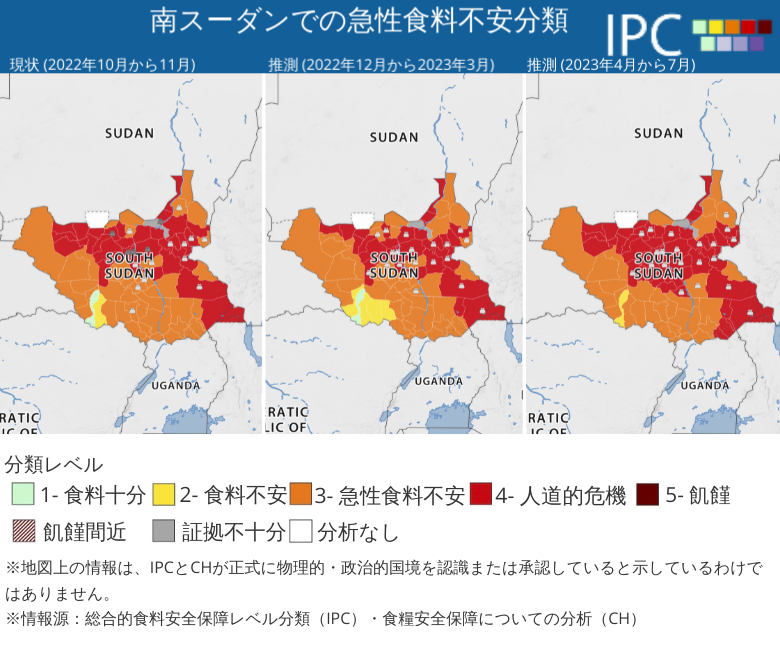

In addition to the conflicts and flood damage outlined above, the people of South Sudan are facing a severe food crisis. According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), between October and November 2022, about 6.6 million people were in acute food insecurity—roughly 54% of South Sudan’s population. A UN report estimates that between April and July 2023, this number could rise to about 7.8 million. Furthermore, about 1.4 million children are already malnourished. Prolonged child malnutrition is said to impair the normal development of the brain, nervous system, and body tissues. This food shortage is reportedly even more severe than during the peak conflict years of 2013 and 2016.

IPC acute food insecurity classification for South Sudan (translated by GNV from the English original)

Why has the food crisis deteriorated so badly? There are multiple causes. First is flooding: affected people have lost homes, fields, livestock, and grazing lands, which drives food shortages. Conflict is another major cause; people whose assets and crops were destroyed by violence, or who lost livelihoods as they fled, face severe barriers to accessing food. In contrast to the flooding across much of the country, some areas are also suffering from drought. Along the border with Kenya in Eastern Equatoria State, dry conditions have depleted water sources and degraded pastures, leading to shortages of food—and possibly fueling robberies and attacks in the border area.

Although extreme weather and conflict have deepened food insecurity, humanitarian aid has been insufficient. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), funds delivered to South Sudan fall short by more than 30% of what is required. The World Food Programme (WFP) has long provided food aid to South Sudan, but in 6/2022 it suspended some assistance due to insufficient funding. One reason for the funding gap is the lack of global attention to South Sudan. In its annual ranking that considers political responses and other factors, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) listed South Sudan among the top 10 “most neglected” displacement crises in 2021. By contrast, NRC noted that funding needs for Ukraine were met in just a single day. Rising global food prices have also hampered aid: when prices surge, the same amount of money buys less food. Although this problem predates the Ukraine war, that conflict has exacerbated it.

Outlook for South Sudan

Since the peace accord in 2018, conflict in South Sudan has eased to some extent, and in 2022 some commitments—such as unifying the forces—were at least partially realized. While the country appears to be inching toward peace, a closer look reveals delays in implementing agreed measures and continued conflict at both national and regional levels. Severe flooding and the associated food crisis have also created a harsh environment for civilians.

Economically, the situation is unfavorable as well. The oil industry accounts for most of the economy, but investment from abroad has declined due to instability and political corruption, and the global shift toward decarbonization has further contributed to a downward trend in oil revenues. As a result, government income has also fallen, raising concerns about the stability of state functions.

As noted at the outset, the 2018 peace agreement’s timeline has been extended by two years. Despite ongoing conflict, natural disasters, and economic crisis, the key will be how much progress can be made in implementing the agreement’s processes over these 2 years.

Note 1: The referendum to determine whether the Abyei area belongs to Sudan or South Sudan has long been postponed, due to disagreements between the two countries over who qualifies as a “resident.” Sudan argues that the Misseriya—nomadic herders who move seasonally between Sudan and Abyei—should be included as residents of Abyei, while South Sudan argues they should not.

Note 2: ACLED stands for the “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.”

Note 3: The Bor massacre was a mass killing of civilians in 1991. It was carried out by a Nuer group led by Machar shortly after he split from the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, and about 2,000 Dinka were killed.

Writer: Koki Ueda

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

民族どうしで代理戦争させるとか最悪ですね、。

それはそう。

南スーダンの他の国でも聞きますが、歴史的に民族対立を引き起こしてきた大国は、解決に向けての責任を負うべきだと感じます。。

今、ウクライナ戦争が注目されています。ウクライナ戦争でこれ以上犠牲者が出ないことを願っています。一方、ウクライナ以外でも、戦争が起きている国がたくさんあり、それらについても、知る必要があると思いました。