[This article contains content related to alcohol and alcohol dependence. Please be mindful of your physical and mental condition as you read.]

People cheerfully drinking alcoholic beverages to upbeat music and pleasant backdrops. In countries where alcohol is consumed, such commercials and advertisements are frequently disseminated. However, the number of deaths attributable to alcohol is about 3 million people worldwide each year. Moreover, deaths and disabilities attributable to alcohol account for 1 in 20 of the combined total. This is roughly the same as those attributable to tobacco and 5 times the number attributable to illicit drug abuse. In a study conducted in the UK that assessed alcohol, legal drugs, and illegal drugs to determine which causes the greatest physical and social harm to users and non-users, alcohol ranked first, ahead of heroin, cocaine, tobacco, and cannabis. Why, even as regulations on drugs and tobacco tighten around the world, is alcohol largely left unchecked? We delve into the reality.

Alcoholic beverages lined up throughout a store (Photo: Toronto Eaters / StockSnap.io [CC0 1.0])

目次

Physical effects of alcohol

The negative effects of alcohol can be broadly divided into 2 types: physical effects and social effects. Here, we analyze alcohol’s impact from these 2 perspectives.

First, as for physical effects, drinking is said to cause a variety of diseases. As a premise, alcohol is a toxin that should be eliminated from the body. Human alcohol metabolism occurs in two stages: once ingested, alcohol is metabolized into the relatively toxic compound acetaldehyde, and then into the relatively non-toxic acetate. When alcohol is consumed and converted to acetaldehyde, signs of intoxication such as facial flushing, headache, nausea, and increased heart rate occur. Diseases caused by the accumulation of drinking include cirrhosis, acute and chronic pancreatitis, heart failure, hypertension, depression, stroke, and cancer. A dangerous aspect of drinking is that harm to the body accumulates gradually over the long term, so the body may be crying out while the person doesn’t notice.

Alcohol also stimulates the brain and triggers the release of dopamine, a reward-related chemical. This links positive feelings with drinking in the brain and creates a desire to drink more. In other words, once alcohol enters the body, the likelihood of becoming dependent on it becomes very high. Of course, consuming alcohol once does not immediately cause addiction; there are various other factors ((※1)). And because it is a brain disease, a person’s lack of willpower is not the issue. When alcohol dependence develops, drinking becomes habitual and intake tends to increase as a result. This greatly raises the risk of the above diseases and can also significantly affect mental health, including triggering depression. As with other addictions, when blood alcohol levels drop in alcohol dependence, patients develop withdrawal symptoms such as trembling, headache, and anxiety. To escape these symptoms, people may repeat a cycle of drinking again even when they know it’s not good to do so.

Beyond the long-term dependence described above, there is also acute alcohol intoxication, which has short-term effects. Acute intoxication can cause vomiting and headaches and, in the worst cases, death due to hypotension, coma, or respiratory distress caused by elevated blood alcohol levels, or suffocation from aspirating one’s own vomit. It is also said that the effects of drinking are far greater on young people whose bodies are not yet fully mature compared to physically mature adults. The impact of alcohol on the young brain is particularly large and can be a cause of brain atrophy.

The physical effects of alcohol do not fall only on the person who drinks. Drinking during pregnancy affects the fetus before birth and can lead to developmental disabilities and congenital anomalies after birth. This is known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (commonly FASDs). Infants can also be affected via breast milk from a drinking mother.

A poster warning against drinking during pregnancy in English and Spanish (Photo: Angie Linder / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Social effects of alcohol

Thus far we have outlined the effects of alcohol on the body, but its social impact is also immense. Here we look at alcohol’s social effects.

First among social effects is the association between crime and alcohol. Two alcohol-related crimes to highlight are “drunk driving crashes” and the link between alcohol and violence.

First, regarding drunk driving: In 2016, 10,497 people died in alcohol-impaired traffic crashes in the United States. This accounted for 28% of all traffic deaths in the country. Many countries strictly crack down on drunk driving, and license revocation and even imprisonment are not uncommon. Nevertheless, the harm persists. It should be noted that the victims of drunk driving crashes are often not only the perpetrators themselves but also unrelated people who are caught up in these incidents.

A banner raising awareness about drunk driving crashes (Thailand) (Photo: Nathan LeClair / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Next, the link between alcohol and violent crime. Research has shown a strong association between excessive alcohol consumption and violence research. Alcohol weakens the brain mechanisms that normally suppress impulsive behaviors such as aggression, leading to inappropriate judgment and overreactions. For example, an intoxicated person might mistakenly feel threatened by something trivial, become aggressive toward the other party, and escalate to violence. Since alcohol can heighten not only anger but other emotions, there is also a risk of suicide and errors in judgment arising from intense sadness or agitation as indicated. In a 2007 study in Australia, about 4.5% of Australians aged 14 and over were victims of alcohol-related violence. Alcohol-related domestic and intimate-partner violence is also a serious problem.

In extreme cases, alcohol-related violence can escalate to homicide. One study concluded that about half (47%) of all homicides in Australia between 2000 and 2006 were alcohol-related.

Drinking also contributes to various forms of harassment. In Japan, alcohol coercion has become such a problem that there is even a term for it: “aluhara (alcohol harassment).” While about 10% reported having perpetrated aluhara, about 40% reported having experienced it, according to a survey.

There are also claims of a strong relationship between drinking and poverty. Many people experiencing poverty or social difficulties want to escape daily stress and anxiety, and some turn to alcohol because it is inexpensive and readily available. This is related to alcohol being a depressant (“downer”) that acts on the parasympathetic nervous system. However, while alcohol may temporarily distract them, the factors driving them into poverty and making social life difficult are structural, so the root causes are not removed and the stress and anxiety continue. If drinking becomes a habit to seek temporary relief, intake gradually increases. Then health problems may arise, and the risk of dependence increases, making it difficult to work as before. Or the cost of alcohol may begin to strain the household budget, resulting in a worsening of poverty. Even for those not initially in poverty, using alcohol as a response to stress can be one factor leading to poverty.

There is also a proven causal link between harmful drinking and the incidence of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS. This is believed to be due to engaging in risky sexual behavior or contact without proper judgment while intoxicated, increasing the risk of infection.

Problems with alcohol marketing and its impact

Why, despite causing so many harms, has alcohol become so widespread and established as a luxury/pleasure good? A major reason is the extremely strong, privileged position of alcohol marketing. Here we highlight the scale of the problem.

Alcohol is advertised on a very large scale and in highly impactful ways. In terms of scale, AB InBev, the world’s largest brewer, is the world’s 9th-largest advertiser, with global ad spend of 6.2 billion USD in 2017. This easily exceeds the 4 billion USD spent by Coca-Cola, a company known for its massive global marketing. A common feature of these ads is that they portray alcohol as attractive and associate it with good times, good feelings, friendship, and success. By linking alcohol with images such as sports and youthful moments, they instill positive impressions in consumers.

Mexican beer promoted with sports-related advertising (United States) (Photo: beavela / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Alcohol marketing employs many tactics, notably featuring drinks in entertainment such as movies and TV dramas. In the top 100 highest-grossing Hollywood films each year from 1996 to 2015—that is, 2,000 films in total—alcohol appeared in 87%. Is the frequent appearance of alcohol in films a coincidence, or part of alcohol companies’ marketing? While not every movie that features drinking is funded by alcohol companies, there are confirmed cases where companies sponsor films in which their brands appear. Given that specific alcohol brand names appeared in 44% of those 2,000 films, it is clear that some of this is indeed part of marketing.

Such portrayals of alcohol in movies are said to significantly influence young people’s drinking ((※2)). Alcohol marketing also clearly employs strategies that target youth. Young people are potential future customers for alcohol companies. For example, a study of U.S. middle school students found that the more alcohol ads eighth graders had seen, the more likely they were to drink in eighth grade. Another study found that teens who owned promotional items such as caps or T-shirts with alcohol brand logos were nearly 2 times as likely to drink as those who did not, showing how effectively alcohol marketing works on youth. The industry also actively engages in sports marketing, targeting young viewers who make up a large share of the audience.

There is also a social issue in equating people with above-average alcohol metabolism—those said to be “good at holding their liquor”—with being strong. In particular, because companies often see a business opportunity among women, who drink at lower rates, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that “alcohol marketers often portray women’s drinking as a symbol of empowerment and equality.”

How marketing differs from tobacco

How does the marketing of the tobacco industry, which is similarly criticized for physical and social harms, differ? Due to strong social headwinds, advertising and other regulations have become stringent globally for tobacco, especially in high-income countries. In the United States, under the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, the four major tobacco companies agreed not to market to minors under 18. This includes bans on tobacco brand sponsorships of sports and entertainment events, free tobacco giveaways, and sales via vending machines—strict regulations by any measure. By contrast, even in the U.S., there are virtually no agreements restricting alcohol marketing to young people; the law merely prohibits drinking under the age of 21.

Cigarettes and beer (Photo: Alex Brown / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

There is also a big difference in how tobacco and alcohol are treated in movies and TV shows. In 2000, depictions of smoking appeared in 98 of the top 100 box-office films in Hollywood, but after regulation, that number fell to 22 in 2002. The downward trend in smoking depictions has continued slowly to the present. Meanwhile, the number of films featuring alcohol increased by an average of 5% annually over 20 years.

Two harmful commodities—why the disparity in treatment? There are mainly 3 reasons.

First is the difference in perceived harmfulness. Alcohol has been shown to have harmfulness comparable to tobacco ((※3)). But for alcohol, there is a gap between scientifically established harms and commonly perceived harms. It is now common knowledge that tobacco use greatly increases smokers’ mortality risk. This perception is far removed from that of alcohol. In addition, because there is essentially no safe level of tobacco use, the focus of regulation is “cessation.” By contrast, with alcohol, some claim that moderate drinking can be healthy in some cases, which prevents widespread recognition of its harms.

The second is the difference in the networks advocating regulation. Groups seeking to regulate alcohol became fragmented into three approaches (public health, moral responsibility, and medical issues), dispersing their advocacy. This stems from the policy failures of the Prohibition era. From the late 19th to the 20th century, moves to regulate alcohol emerged in Western countries and prohibitions were enacted, but they largely failed. Since then, advocacy for alcohol regulation has been split among the three approaches above, diluting the message. Tobacco, by contrast, avoided such fragmentation and pressed for regulation with a more unified voice, helping drive progress. Another reason is that international cohesion around tobacco control emerged much earlier than for alcohol.

The third is the policy environment. In tobacco control negotiations, the tobacco industry was not only excluded but formally recognized as an obstacle. Thus, in the international tobacco control context, there was no need to accommodate the industry by weakening regulation, even if it could not be entirely ignored. Learning from tobacco’s experience, the alcohol industry chose to support regulatory frameworks and succeeded in maintaining a certain degree of standing within policymaking, continuing to acknowledge the dangers of excessive drinking while working to prevent the notion that alcohol is wholly harmful from taking hold.

Why alcohol marketing is favored

Why is the alcohol industry favored to such an extent?

The biggest reason is likely the economic impact of alcohol. People who drink alcohol account for 42% of the world’s population. Global retail sales of alcohol in 2018 are estimated to have exceeded 1.5 trillion USD, about twice Japan’s national budget of 860 billion USD that year. In the U.S., annual tax revenue from alcohol is about 69 billion USD, comparable to five years of funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The Chinese distiller Kweichow Moutai ranked 16th worldwide by market capitalization across all sectors in 2021, underscoring the massive economic impact. This enormous scale makes regulating the alcohol industry difficult.

Alcoholic beverages lined up in a bar (Taiwan) (Photo: weichen_kh / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

As in other industries, lobbying ((※4)) is also active in the alcohol industry—and can even cross borders. For example, when Kenya proposed adopting warning labels for alcoholic beverages in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in light of alcohol’s effects, European Union (EU) countries expressed concerns and blocked the policy, reportedly influenced by industry-led lobbying.

Countries that prohibit alcohol

Thus far, we have mainly discussed how alcohol use affects societies where alcohol is consumed. There are also countries that prohibit alcohol.

Most countries that prohibit alcohol do so based on Islamic teachings. In particular, Saudi Arabia strictly prohibits alcohol; there are cases where foreigners possessing alcohol have been arrested and sent to prison. In the Quran, Islam’s holy book, God acknowledges that alcohol may have some benefits, but judges that its harms outweigh any benefits, and therefore “God has forbidden intoxicating drinks.” While most Muslims interpret “intoxicants” to mean alcohol itself is prohibited, in reality a certain number of Muslims do consume alcohol.

However, many countries that prohibit alcohol allow non-Muslims and foreigners to drink legally. There are also countries with Muslim majorities but no national prohibition, such as the United Arab Emirates (except in the emirates of Sharjah and Dubai).

Prohibition is not limited to countries whose laws are based on Islam. In parts of India, alcohol is banned to improve public health. This is based on Article 47 of the Indian Constitution, “The Duty of the State to raise the level of nutrition and the standard of living and to improve public health,” and is considered part of fulfilling that duty.

A government-licensed alcohol store (India) (Photo: Michael Cannon / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Responses being taken

Not everyone is silently overlooking these realities about alcohol. Various efforts are underway—from the international level to national governments and even grassroots civil society.

One international initiative is the “Global Status Report on Alcohol Policy” released by the WHO in 2004. However, this merely summarized the international situation and did not push forward an international agreement to regulate alcohol. In 2018, the WHO also launched “SAFER”, a movement to raise alcohol prices through excise taxes and pricing policies. The WHO is urging governments to impose price measures to regulate alcohol. Nevertheless, alcohol regulation is heavily influenced by national laws and customs, making a large initiative within an international framework unlikely in the near term.

A meeting on alcohol policy in the EU (Estonia) (Photo: EU2017EE Estonian Presidency / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

There are also examples of national-level regulation. The most common is age-based control. In many countries, drinking by people below a certain age—around 20—is prohibited. However, many countries have no legal drinking age at all, and even where laws exist, they are often widely ignored, raising doubts about effectiveness.

Some countries regulate by raising purchase hurdles through alcohol taxes or price increases. Higher prices can curb consumer alcohol purchases. The WHO Regional Office for Europe led 53 countries in adopting targets to reduce alcohol consumption, resulting in strengthened policies and interventions across much of Europe. However, price increases carry a major concern: they may contribute to the “negative cycle of poverty” described above.

Restrictions on where and when alcohol can be sold can also be useful. For example, in South Africa, when alcohol sales were temporarily banned as part of COVID-19 measures, hospital admissions for trauma declined. While the sales ban was only one factor, experts believe a causal relationship exists. Similarly, in Germany, a causal link has been found between nighttime sales restrictions and reduced hospitalizations. In Latin America, some countries implement temporary alcohol bans around elections. As noted above, crackdowns on drunk driving have also been strengthened. However, in Scotland, a stricter legal limit on drunk driving had no significant effect on the number of crashes.

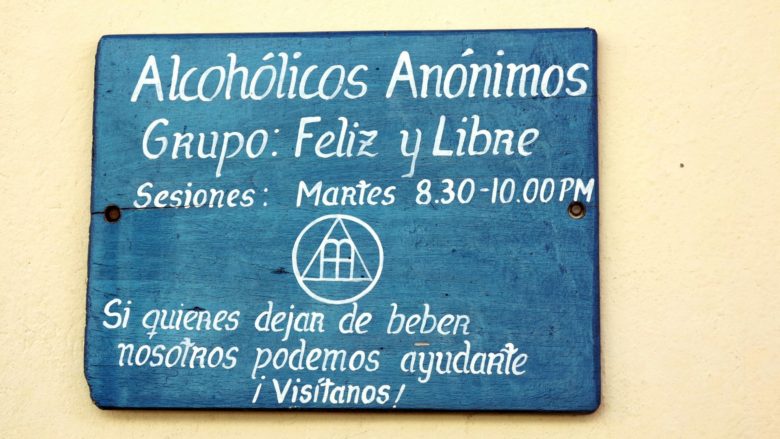

Finally, at the grassroots level, consider Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which operates in about 160 countries worldwide. AA is a mutual-help group in which people with alcohol dependence gather and share their experiences to support one another, and anyone can participate. In the U.S., research has shown that treating men for alcohol dependence significantly reduced both physical and psychological violence toward their wives.

A sign announcing an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting (Cuba) (Photo: Reinhardt König / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

There is also a trend toward reducing alcohol’s inherent harm. Out of concern for alcohol’s effects on the body, the share of low- and no-alcohol products continues to grow. In 2020, these products accounted for 3% of the alcoholic beverage market across the top 10 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, South Africa, Spain, the UK, and the U.S.), which together consume 75% of alcohol, and this share is forecast to grow by 31% by 2024. It is unclear whether this trend is purely a response to consumer demand or a preemptive move by companies anticipating stricter regulations.

Outlook and conclusion

This article has examined the harms of alcohol and the current situation in which it remains largely unchecked. Certainly, moderate drinking may have aspects of a pleasure good. However, given the wide-ranging physical and social harms alcohol causes, is it not odd that it is not strictly regulated? Through overt marketing, alcohol turns large numbers of people—especially children and youth with their futures ahead—into people with alcohol dependence. Even as national and grassroots regulations exist, we must not lose our critical gaze in the face of a complete lack of regulation within an international framework.

※1 The factors that lead to addiction fall into four broad categories: biological, environmental, social, and psychological.

※2 A study of French youth examined whether portrayals of alcohol in films affected desire to drink depending on context. When alcohol appeared in positive scenes—tokens of friendship or celebrations—it increased the desire to consume; when portrayed in negative contexts—addiction or violence—it deterred consumption.

※3 In terms of deaths, tobacco causes more (alcohol causes about 3 million; tobacco causes about 8 million, including around 1.2 million from secondhand smoke). However, as noted in the introduction, the combined number of deaths and disabilities attributable to the two is roughly similar, hence the description.

※4 Lobbying refers to all activities carried out with the aim of directly or indirectly influencing the formulation or implementation of policies and decision-making related to legislation or regulation.

Writer: Yusui Sugita

yes, you are right.

It is Haram in Islam