In September (9), 2022, an important ruling on Maasai land use was handed down in Tanzania, Africa. Regarding the eviction of the Maasai from their ancestral lands by the Tanzanian government in 2017, the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) (※1) found the government’s actions to be lawful. The government had long demanded that Maasai residents leave on the grounds of protecting the ecosystem in Serengeti National Park. The violent evictions carried out in 2017 are said to have affected 20,000 Maasai people and 5,800 households. Even after 2017, there were reports of violent acts such as burning the homes of Maasai who refused to leave and firing on protesters.

With regard to these actions by the Tanzanian government, the court ultimately ruled them lawful. It has been pointed out that this decision could encourage rights violations in the name of conservation. Although the government invokes conservation, it is doubtful whether evicting residents actually leads to protecting nature. In fact, this kind of case is not limited to Tanzania. Violent evictions under the banner of conservation are occurring elsewhere in Africa as well. Why is this happening? This article explores the background and the reality.

A Maasai pastoralist (Photo: safaritravelplus / Wikimedia [CC0 1.0])

History of evictions

Let us first look back at the history of the Maasai in East Africa. The Maasai have historically been pastoralists leading a nomadic way of life. Today, many Maasai who maintain this traditional lifestyle live mainly in northern Tanzania and southern Kenya. It is said that the Maasai once lived in the lower Nile region near present-day northwestern Kenya. They began moving south around the 15th century, and by the mid-17th century had migrated to what is now East Africa, where they live today.

Evictions under colonial rule began around the 19th century. At the Berlin Conference held between 1884 and 1885, European powers drew borders for African colonies, and the region corresponding to mainland Tanzania was occupied by Germany. In 1895, the German Land Ordinance was enacted, placing all lands deemed “unused” under the control of the German crown. The Maasai, on the grounds that they were nomadic, were denied rights to the lands where they lived and were forced to vacate, except for a few areas. The German Land Commission established in 1907 declared, “The Maasai committed robbery and were expelled, so they have no rights to the land,” and seized Maasai lands as crown land. The dispossession of Maasai land and rights dates back to this period. In addition, because agricultural policies in these lands did not go as well as the German government had hoped, the establishment of nature parks was considered as an alternative land use. Although the plan was ultimately abandoned, it is noteworthy that the concept of “conservation” existed even then.

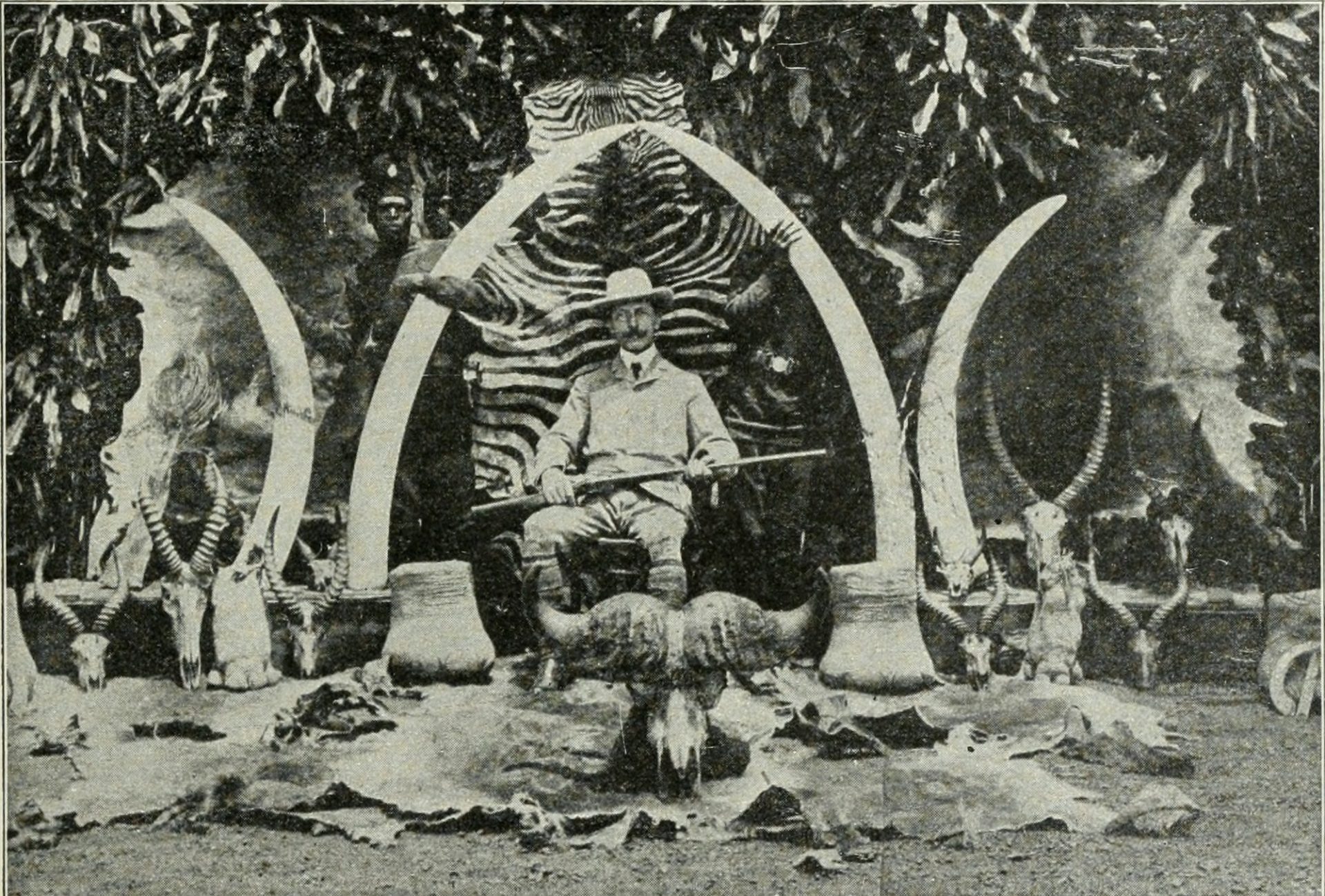

Illustration of hunting in the colonial era (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images / Flickr [CC0 1.0])

During World War I, Britain defeated Germany and took control of the territory. After the war, present-day mainland Tanzania was placed under British administration (※2). Under British colonial rule, a Hunting Ordinance was enacted in 1940. This ordinance created Serengeti National Park and game reserves in areas where the Maasai lived, and restricted uses such as settlement and grazing. However, because the ordinance did not apply to people originally residing within national parks, the Maasai were not significantly affected at that time.

Further regulations followed in the name of conservation. In 1957, Serengeti National Park was split into two: Serengeti National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, and all human habitation was banned within the national park to protect flora and fauna. As a result, the Maasai were confined to living within the conservation area. In 1959, the National Parks Ordinance was enacted. It authorized the colonial governor to establish national parks in Tanzania and simultaneously extinguished all rights within those parks held by anyone other than the governor. This law meant the complete extinguishment of Maasai rights within the parks.

That same year, an ordinance was also enacted for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (Ngorongoro Conservation Area: NCA), to which the Maasai were relocated. It explicitly recognized the Maasai’s right to reside within the conservation area. Nevertheless, the NCA’s management body was given the authority to restrict various activities in the area, such as cultivation and grazing. Moreover, although Maasai were initially included in the NCA’s governance structure, they were excluded in the 1960s.

Mainland Tanzania gained independence in 1961, but residents’ rights continued to be suppressed, for example with the enactment of the Wildlife Conservation Act restricting activities in game areas. The Ngorongoro Conservation Area was inscribed as a World Heritage site in 1979, and Serengeti National Park in 1981, and both were increasingly used as tourism resources. The Maasai thus saw their living areas further narrowed and their livelihoods progressively restricted.

In this way, the rights of residents such as the Maasai were continually stripped away by the government during the colonial era and even after independence. In 2017, the Tanzanian government demanded that residents living in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area move out, citing the need to protect nature. The government carried out violent evictions against Maasai who refused, leading to a case before the EACJ. This is the incident that led to the ruling mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Triggered by this lawsuit, the court battle over Maasai rights and government-led evictions continued for 5 years. In 2018, in response to the Maasai’s complaint, the court once issued an injunction against the Tanzanian government’s evictions. Nevertheless, even after that ruling, the government did not stop the violent evictions. And in September (9), 2022, the court handed down its final decision that the evictions were lawful. The government claims that the 2017 evictions were carried out in accordance with the law and with due respect for residents, while Maasai representatives assert they suffered harm from violent evictions. The court ultimately concluded that the evidence supporting the Maasai’s claims was insufficient and ruled “lawful” in favor of the government’s position.

Why does the government demand evictions?

Why is the government going so far to expel residents? Germany and Britain once pursued colonial policies to control land in Africa, including Tanzania, with the aim of securing mineral resources, vast fertile lands, and the people living there as a labor force. Tanzania has abundant gold resources, which are now a major export. Agriculture is also thriving on its fertile land, with over 40% of the country used as farmland for the production of crops such as maize. During the colonial era, a hut tax was introduced that required payment per dwelling. Residents who had previously lived self-sufficiently now needed cash to pay the tax and were forced to work in construction and mining as demanded by the colonial government.

In addition, there was likely an aim to secure hunting grounds for valuable trade goods from animals, such as ivory. Trophy hunting as a sport also took place in Tanzania, and hunting grounds were secured for that purpose as well. For colonial governments, obtaining game animals and hunting grounds was extremely important, and they promoted “conservation” to protect those animals. During the colonial period, residents such as the Maasai were expelled from their traditional lands primarily for these reasons.

Maasai and wildlife in Tanzania (Photo: David Roberts / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

What, then, is the intention behind the evictions carried out by the Tanzanian government after independence? One of the reasons the current government demands evictions is the profit obtained from tourism, including hunting and safaris. Tourism has played a crucial role in Tanzania’s economic development. According to the World Bank, as of 2019 tourism was Tanzania’s largest source of foreign exchange and the second-largest contributor to GDP. The number of tourists visiting Tanzania that year reached 1.5 million, underscoring the importance of tourism to the country.

Benefiting from such tourism, the government is said to be evicting residents from national parks and conservation areas—tourism resources—so that more tourists can visit. In conservation areas, long-established residents such as the Maasai have long coexisted with nature and ecosystems. Nonetheless, the government, under the banner of protecting nature, is trying to drive out residents and place these areas under its control. Under the Multiple Land Use Model (MLUM) plan proposed by the Tanzanian government, it has been estimated that if the Maasai manage the Ngorongoro Conservation Area and the government cannot fully utilize it as a tourism resource, it would lose half of projected profits by 2038. The desire to avoid such losses is likely another factor behind the evictions.

Close relationships between the government and hunting companies are also said to drive evictions. Tanzania attracts many tourists for hunting, and numerous companies provide such services. The government grants these companies hunting areas and rights and in return receives funds. For example, the UAE-based hunting company OBC (Otterlo Business Corporation) was first granted land by the Tanzanian government in 1993. In return, the government is said to have received millions of US dollars.

Such ties, which generate profits for the government, can become reasons to force the Maasai out. There is also a hunting company called Green Mile that committed serious violations of conservation regulations yet later again received hunting permits from the government. This suggests the Tanzanian government may be conducting evictions that violate residents’ rights not for conservation, but for its own benefit.

A safari in Tanzania (Photo: Colin J. McMechan / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Similar cases in other countries

Cases in which residents’ rights are violated in the name of conservation are not limited to Tanzania. For example, in Kenya there is a history of Maasai land and rights being continuously taken away. As in Tanzania, residents were forced to move during British colonization. Maasai living in what is now Kenya were stripped of their ancestral lands by settlers and moved to “reserves.” Britain claims these relocations were based on two treaties signed in 1904 and 1911. However, some argue that the Maasai did not fully understand the treaties when they signed them due to language and other issues. Moreover, the reserves to which they were moved were far from ideal. Residents were strictly controlled, subjected to forced labor such as road construction, compulsory schooling, and quarantine restrictions. As in Tanzania, the introduction of a hut tax burdened Kenyan residents as well.

In recent years, residents have been removed to implement the Natural Resource Management Project (NRMP) funded by the World Bank. Under the guise of conservation, boundaries of existing forest reserves were changed and residents living there were evicted. Kenya’s constitution, revised in 2010, stipulates that the customs, lands, and rights of communities that have lived in forests since time immemorial must be protected. Nevertheless, the government made decisions without any consultation, burned homes, and forced people out. Receiving support from the World Bank, the Kenyan government also seeks to justify evictions by labeling forest residents as “illegal squatters,” equating them with internally displaced persons in its statements to the press.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, residents have also been violently evicted in the name of conservation. In 1970, Kahuzi–Biega National Park was established in eastern DRC. At its creation, approximately 6,000 Batwa people, who had lived there since their ancestors’ time, were evicted without consultation or compensation. The park was inscribed as a World Heritage site in 1980. Various species live in the park, including gorillas listed as endangered on the Red List (※3). Under the pretext of protecting such species, violent evictions against residents have continued. According to a report investigating violence from 2019 to 2021, park rangers and the Congolese army burned villages and used heavy weapons against residents, and at least 20 Batwa people were killed over 3 years.

People photographing gorillas in Kahuzi–Biega National Park (Photo: Advantage Lendl / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

In Cameroon, the government—supported by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), an international NGO dedicated to conservation—has been accused of violating the rights of the Baka people, who traditionally live in Cameroon. Many endangered species inhabit the country’s national parks. The Baka living in these parks are hunters, yet their hunting is said to have very little impact on nature. Despite this, they have been banned from entering hunting grounds and their livelihoods have become untenable. Meanwhile, the forests taken from them are used for poaching or as land for tourist safaris. WWF provides funding to the national parks and to a group called eco-guards that patrol to prevent poaching. Although they are supposed to protect nature, these eco-guards have repeatedly engaged in violence by destroying Baka homes, forcibly evicting residents, and seizing property.

“Conservation” as a pretext

Across Africa, long-established residents continue to be forcibly removed, and “conservation” is used as the pretext. One rationale for demanding evictions in the name of conservation is the overpopulation theory: the idea that increases in human and livestock populations harm the environment, and that removing people and livestock from nature will solve the problem.

But some argue this lacks scientific basis. The Maasai have in fact coexisted with local ecosystems without imposing a heavy burden on nature and wildlife, and their stewardship has been credited with fostering biodiversity. Traditional communities have accumulated knowledge of managing and conserving local nature, water, and land through agricultural techniques. Government eviction demands that ignore this cannot be said to be legitimate. Far from harming nature, many of those who have been forced out have protected it and lived in harmony with it. Although people who maintain traditional lands and customs account for less than 5% of the world’s population, they safeguard about 80% of global biodiversity.

It has also been pointed out that hunting can harm conservation. While hunting generates substantial economic benefits that some say can be reinvested in conservation, there are ethical issues and concerns that an anthropocentric mindset will increase harm to wildlife. Moreover, unless the government strictly manages national parks, illegal hunting may become widespread, undermining conservation.

Maasai dwellings in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (Photo: George Lamson / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

What should the government truly “protect”?

As we have seen, the government has used “conservation” to expel residents who have long lived in harmony with nature. Many residents have had their inherent rights trampled, while the government and tourism-related companies reap the benefits. In response, the Pan Afrikan Living Cultures Alliance (PALCA) was established to protect residents’ rights. This is an NGO led by African communities that engages in activities such as protecting residents’ rights, preserving languages, and promoting community-led management of natural resources. A gathering has also been held in which multiple organizations, including PALCA, and community representatives come together to address these issues through film.

There is also an argument that government interests and Maasai rights need not be in conflict. In one reserve in northern Kenya, residents are provided with pasture under certain restrictions. Because planned pastoralism is possible, residents can avoid increasing livestock beyond what is necessary, minimizing impacts on nature. Furthermore, residents are employed in tourism within the reserve and receive a share of the profits. This shows that Maasai pastoral livelihoods and tourism can be successfully balanced, and that solutions are not necessarily either-or.

However, without understanding the tragic reality of evictions, solving the problem will be difficult. Many people tend to imagine beautiful nature as “nature without people.” Tourists expect that kind of landscape, and governments try to provide it to promote tourism. We must first recognize that tourists’ expectations also relate to interventions carried out in the name of conservation. As noted above, it is questionable whether government-led evictions actually lead to the conservation they purport to serve. Evictions rooted in the colonial era run deep in these regions. We must not overlook the violence hidden behind the sweet words of conservation, and we must protect the rights of residents who safeguard nature and live in harmony with it. In doing so, we may hope to protect both “people” and “nature.”

※1 A judicial body of the East African Community based on its treaty, located in Tanzania

※2 After World War 1, the League of Nations designated present-day mainland Tanzania as Tanganyika and granted its mandate to Britain. Tanganyika later gained independence in 1961, and in 1964 united with Zanzibar—which had become independent from Britain in 1963—to form present-day Tanzania

※3 The Red List of threatened wildlife compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources : IUCN)

自然保護と聞くとそれが完全に善だと思い込んでしまうので、その裏で酷い人権侵害が起こっているなど考えもしなかったので驚きでした。

マサイ人が立場の弱い人々であることを悪用して、政府の都合によって追い払われた事実に衝撃を受けました。法廷でも政府寄りの見方をしているので、マサイ人がどのような救済を受けることができるのか気になります。

「という名のもとに」系は要注意。

「SDGs」も一部でひどい使われ方をしている。