In 2021, a mobile money startup based in Senegal called Wave(Wave) raised 200 million US dollars in funding, as reported. At first glance, Wave’s service looks similar to traditional payment services like PayPal(PayPal) in that users can easily deposit and withdraw money, transfer funds, and pay bills on a smartphone screen. However, Wave is groundbreaking compared with conventional cashless payments because all services can be used simply by creating an account, even without a bank account or credit card. Since opening bank accounts is difficult for low-income people, bank account ownership rates are low in Africa; this makes services enabling cashless payments without a bank account highly sought after.

In 2021, eight other startups across the African continent also achieved fundraising rounds of over 100 million US dollars, ushering in a “mega-round(※1) era” for African startups. As will be discussed later, recent investments in Africa can be seen as a positive trend, qualitatively different from previous investment patterns by high‑income countries that were considered exploitative. At the same time, startups are facing Africa-specific, formidable challenges. This article explores both the bright prospects and the shadows.

Wave’s website, photographed on July 21, 2022 (Photo: Koki Ueda)

目次

From exploitation to mutual benefit

It is well known that during the eras of the slave trade and colonialism, Africa suffered unjust exploitation by the high-income nations then known as the great powers. Even after African nations gained independence in the 1960s, certain types of investment by high‑income countries arguably continued to lead to exploitation. This is the phenomenon commonly called “neo-colonialism.” For example, in sectors like mining and agriculture, foreign companies with ample capital have been seen engaging in unfair dealings that amount to resource extraction. There have also been problems of illicit capital flight through practices such as foreign firms’ tax avoidance tied to such investments and trade.

By contrast, recent investments in startups tend to grant African businesses a meaningful degree of operational control, which is favorable compared with traditional investment patterns. The promising business models themselves are recognized by global investors; companies can use investors’ capital to build, scale, and monetize their businesses, while investors receive distributions in return—creating a mutually beneficial relationship.

The remarkable rise of African startups

Startups are companies in the earliest stages of their business. Typically, such companies have limited revenue but need significant capital to launch operations, necessitating fundraising from sources like venture capital(※2). In 2020, no African startup raised over 100 million US dollars, but in 2021, alongside fiscal stimulus and monetary easing by governments and central banks in response to the pandemic, the global money supply expanded, and mega-rounds of 100 million dollars proliferated.

This trend did not begin only in 2021. In recent years, the number of African companies securing substantial funding has surged. According to a study by consulting firm BCG, the number of African startups securing venture capital has been growing at around 46% annually between 2015 and 2020. Compared to the global average growth rate of about 8% per year, that’s roughly six times faster.

Focus on tech companies

In particular, tech companies are attracting large sums from globally renowned institutional investors. In 2021, the total raised by African tech startups reached 2 billion US dollars, three times the previous year. Nigeria-based fintech (※3) firm OPay(OPay) provides POS machines as a lightweight alternative to ATMs and handles QR code payments. It raised 400 million US dollars from Japan’s SoftBank, China’s Sequoia Capital China(Sequoia Capital China), and five other firms. Another Nigeria-based fintech, Flutterwave(Flutterwave), offers a platform enabling payments between users of different payment services. It raised 170 million US dollars from Avenir Growth Capital(Avenir Growth Capital), Tiger Global Management(Tiger Global Management), and others. There is also investment from within Africa: MFS Africa(MFS Africa), which provides a platform similar to Flutterwave’s, raised about 100 million US dollars from investors including South Africa’s AfricInvest(AfricInvest).

Why has funding flowed into African tech startups in recent years? There are multiple reasons. First, Africa has a population of over 1 billion with a low median age and strong growth prospects. Rising consumer numbers naturally boost company revenues. Internet penetration is also improving: between 2000 and 2021, Africa’s total internet user base increased 130-fold. In addition, markets for electronic payments, e-commerce, and software have high growth potential. For example, Kenya’s mobile money service M‑Pesa(M-pesa), launched in 2007, saw its number of accounts reach 90% of the country’s adult population by 2016. The application of technology goes beyond fintech to areas such as agriculture and healthcare. For these reasons, global investors appear increasingly drawn to African tech firms.

A long road to business stabilization

From the foregoing, one might assume African companies are all progressing smoothly, but that is not the case. They face steep hurdles. Some challenges are visible when we look at which stages of fundraising startups are reaching, so let’s begin with that perspective.

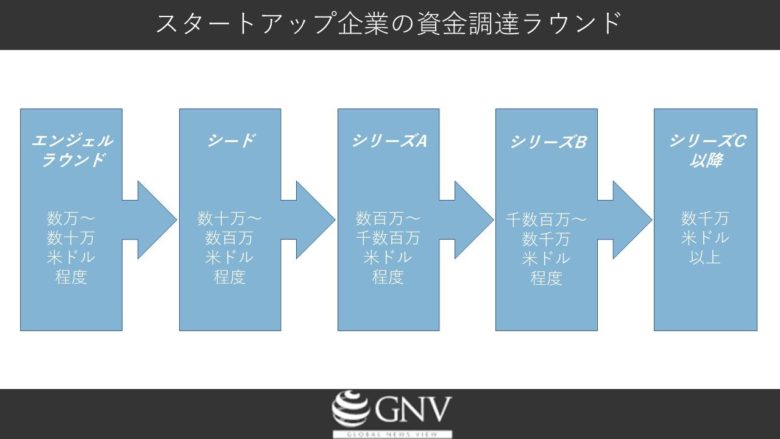

Here is how startups typically progress through funding rounds.

Startup funding rounds (created based on information from utokyo-ipc)

The first stage involves angel or seed investment. Next is Series A, conducted after a prototype is complete and product delivery has begun. Then comes Series B, for scaling once the business is on track. After that are Series C and beyond, typically when profitable operations have stabilized.

Many African startups have not yet gotten their businesses on track or achieved stable profitability. In fact, most startups reportedly have not been able to raise Series B rounds or later.

According to BCG’s study, in 2019 a few firms in Africa did manage to raise Series C or later, but even compared to 2014, the share of companies reaching Series B and beyond remains small. Compared with the United States, the proportion is clearly lower. Thus, only a very small number of African startups are achieving business stabilization and sustained profitability.

What lies behind this

There are multiple reasons why African companies struggle to stabilize their businesses. First, private consumption is weak. In 2017, Africa’s average GDP per capita was 1,809 US dollars—much lower than the 2017 global average of 10,830 US dollars. Some argue that poverty in African countries has been easing when viewed through the World Bank’s GDP and related criteria for low-income countries, as claimed by some, but the World Bank’s thresholds are extremely low and do not adequately capture Africa’s poverty. Using an “ethical poverty line”—which considers income and life expectancy to gauge whether people can realistically survive—92% of people in Sub‑Saharan Africa live below that line. Most Africans live on the edge. The consumer environment surrounding African businesses is markedly worse than in high-income countries.

Next is the fragile data communications infrastructure. Africa connects to the global internet via submarine cables, but landlocked countries benefit less, and even coastal countries often have only 1 or 2 cable landing stations. As a result, every time a cable cracks or other issues occur, regular slowdowns or outages happen. Over the past 10 years, high‑income countries have adopted fiber‑optic communications to move vast amounts of data, but installing fiber is extremely expensive, so it remains limited in Africa and its benefits are not widely enjoyed.

A submarine cable landing from Kenya that brings internet to all of East Africa (Photo: Jon Evans / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

There are also problems with power supply. Excluding South Africa, the total simultaneous generation capacity of Sub‑Saharan Africa is 68 gigawatts, which is less than that of Spain alone. The resulting power shortages and outages hinder people’s access to the internet. Furthermore, telecom costs are an issue. Japan’s average monthly subscription fee is 47 US dollars, while in Sub‑Saharan African countries it is about 30–99 US dollars per month. As noted, most people in African countries suffer from poverty, yet face telecom costs comparable to or higher than Japan’s. The barrier to internet use is high.

Conflict and political turmoil are further factors. According to data from ACLED, a research organization that collects and analyzes data on conflicts and violence worldwide, in 2021 there were 7 countries in Sub‑Saharan Africa with 100 or more deaths. Political instability is also serious: in West Africa alone, there were 8 coups or attempted coups in the past 1 and a half years. Conflicts and turmoil can force companies to suspend business, and the uncertainty makes investors wary of deploying capital in Africa.

Other factors include the fragmentation of African markets across regions, a shortage of digital talent, and the presence of powerful competitors from large companies outside Africa. In addition, the legal environment for doing business is not always well developed. The Ease of Doing Business index measures whether processes and costs for starting businesses, contracting, and paying taxes are appropriate from a regulatory standpoint. African countries typically rank around 100–190 out of 190 countries worldwide, indicating a less-than-ideal legal environment relative to the world as a whole.

Efforts toward solutions

For startups facing such a range of challenges to achieve business stabilization and sustained profitability, support from national governments through policy and other measures is essential—and such efforts are beginning.

First is the rollout of national innovation strategies. Concretely, governments analyze domestic strengths and identify priority industrial sectors accordingly. For example, Egypt is focusing on its abundant deserts to promote technological innovation in renewable solar and wind energy. Next are policies to stimulate innovation, such as allowing open access to research facilities and data, and providing tax incentives and grants. For instance, Kenya offers corporate tax incentives to firms conducting technological research.

Another key is building an environment conducive to innovation. This includes establishing legal and regulatory frameworks for intellectual property protection and improving learning environments to expand access to STEM education(※4)in science and technology. South Africa launched the technology advancement program “mLab(mLab)” to promote startups and has begun training initiatives for digital health workers(※5).

Student internet café at Lesotho University (Photo: OER Africa / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The African market holds great potential, and indeed substantial capital has begun flowing to startups. These investments are also different from the traditional forms that resulted in exploitation, which is a positive sign. However, challenges such as poverty, fragile data communications infrastructure, uncertain conflict dynamics, and political turmoil create a much harsher environment than in high‑income countries, making business stabilization difficult. While we look to African governments’ support measures, it will also be necessary for countries and companies outside Africa to work together to build an environment in which African firms can compete with the world on a fairer footing.

※1 Mega-rounds refer to the stage at which a startup has raised 100 million US dollars or more.

※2 Venture capital refers to organizations that provide funding—via private equity—to startups and venture companies with high growth potential.

※3 Fintech refers to innovative services that combine finance(Finance) and technology(Technology). Examples include smartphone-based money transfer services.

※4 STEM is an acronym for science(Science), technology(Technology), engineering(Engineering), and mathematics(Mathematics).

※5 Digital health is the application of technology to healthcare. Examples include electronic medical records and telemedicine.

Writer: Koki Ueda

これまで高所得国が負の部分・マイナスの部分をどんどん外部化してうまみを得てきましたが、

その負の部分を負わされてきた低所得国は、今もまだその影響を受けていることがよくわかりました。

グローバル化と言うように世界が容易に繋がれる時代になったからこそ、マイナスの部分・都合の悪い部分をだれかに押し付けて見えなくすることはもう難しいです。

あと、これまでビジネスはハード面が強かった(工場というハコをたてる等)と思いますが、今はITの時代でソフト・無形のものが重要な時代です。なので、大きな資源や土地を持っていなくてもビジネスで勝ちやすい環境があると思います。希望もあるなと感じました。

発展途上国が、豊かな国になるために、自分には何ができるか考えたいと思いました。