On 2022–4–2, the parties to the Yemen conflict began a comprehensive two-month truce by mutual agreement. Since the truce was agreed, reductions in frontline hostilities and increased imports of previously scarce fuel have brought improvements to the humanitarian crisis. And from 6–2, when the truce agreement was due to expire, it was decided to extend the truce for another 2 months. In addition, Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who had long held the post of interim president, resigned on 4–7, and presidential powers were transferred to a newly formed presidential council in Saudi Arabia, outside Yemen.

The Yemen conflict is an armed conflict that began in 2014, primarily between the Houthi movement, which expelled interim President Hadi and seized the capital, and the Hadi government that was driven from the capital together with Saudi Arabia–centered Arab states that support it. In addition to these forces, multiple other actors are involved, and after 7 years of intense warfare, Yemen has fallen into what is called the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, including food insecurity and the spread of disease due to a lack of medical services.

Although this has been a topic covered several times before on GNV, we would like to revisit not only the latest developments but also the conflict’s background, complexity, and humanitarian crisis.

A building destroyed by an airstrike near Aden (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] )

目次

A brief history of the Yemen conflict

First, a brief history of the Yemen conflict. The northern Yemen region became independent as a kingdom in 1918 from Ottoman Turkish rule, and then in 1962 the monarchy was abolished and the Yemen Arab Republic was established. In the south, Aden had been British territory since the 19th century, but in 1967 it became independent as the People’s Republic of South Yemen. The Republic of Yemen was formed in 1990 when North and South Yemen unified. Soon after unification, differences in power and resources between north and south led to confrontation, and the situation was unstable, including an armed conflict from 1990 to 1994.

In 2004, the Houthi movement, a Zaydi branch of Shi’a Islam, took up arms and began an anti-government campaign against the regime led by President Ali Abdullah Saleh. As the first president of the Republic of Yemen, Saleh had maintained an authoritarian system since 1990. In addition to grievances over the economy and politics, the Saleh government’s support for U.S.-led wars such as the 2003 invasion of Iraq intensified the confrontation between the Houthis and the Saleh regime, and the Houthis repeatedly staged anti-government uprisings. However, the battlefield at that time was largely limited to Saada governorate in northern Yemen, the Houthis’ stronghold.

In 2011, the wave of pro-democracy movements across the Middle East and North Africa known as the “Arab Spring” toppled President Saleh. Hadi, who had been serving as acting president, then assumed the presidency, but it was an interim administration with only a two-year term (※1).

In 2014, the Houthis seized the capital, Sana’a, and began advancing south toward Aden, the second city. The government’s base was moved to the southern city of Aden, and the following year, 2015, President Hadi fled to Saudi Arabia. With the president absent from Aden, it became increasingly difficult for the government (hereafter, the interim government) to function and govern. In response to the Houthi advance, Saudi Arabia formed a coalition with other Arab countries, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), claiming the goals of containing the Houthis and restoring the Hadi government (hereafter, the Saudi-led coalition). It took the interim government’s side and began deploying ground forces and launching airstrikes. Seeing an opportunity to return to power, former president Saleh sided with the Houthis. Taking advantage of the chaos, extremist groups such as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State (IS), which had been based in Iraq and Syria, also expanded their presence in Yemen.

Royal Saudi Air Force F-15C (Photo: Saudi88hawk / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

In 2017, former President Saleh and the Houthis split. In 2016, relations had already become unstable after the Houthis condemned Saleh for calling them “militia,” and ties deteriorated rapidly when a senior official and close aide in Saleh’s party was shot dead. In 2017, Saleh announced in a speech that he was formally severing ties with the Houthis and said he was open to dialogue with the Saudi-led coalition; a few days later, he was killed by the Houthis. In 2018, Saleh’s supporters joined the Saudi-led coalition.

There were also divisions among anti-Houthi forces. Separatists advocating independence for the south had fought the Houthis for years alongside the interim government and the Saudi-led coalition, but relations deteriorated over the 2 years from 2017. In 4 of 2017, tensions rose when Hadi dismissed Aden governor Aidarus al-Zubaidi. The following month, thousands of Aden residents took to the streets to protest Hadi and the Southern Movement, which demands autonomy or independence for southern Yemen, resurfaced. The dismissed al-Zubaidi formed the Southern Transitional Council (STC), and confrontation with the interim government intensified.

In 1 of 2018, the STC took control of almost all of Aden and surrounded the presidential palace, triggering fighting between the two sides, and the UAE began backing the STC. The rift between the STC and the interim government/Saudi-led coalition also created a crack between the coalition’s main members, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In 8 of 2019, clashes again broke out in Aden between STC forces and the interim government/Saudi-led coalition, and both sides repeatedly advanced and counterattacked, causing many deaths. However, in 10 of the same year, the UAE announced the withdrawal of its ground forces from Aden.

In 2021, the Houthis launched an offensive on Marib governorate, the government’s last northern stronghold and center of an oil-rich region. In response, Hadi-government/Saudi-led coalition forces intensified airstrikes in Marib; many Houthi fighters were killed, and civilian casualties in Marib in 2021 reached 344 , more than the total for the previous 3 years.

In 1 of 2022, the Houthi push to capture Marib was set back by counterattacks from the interim government/Saudi-led coalition backed by the UAE . In response, the Houthis began launching drone and missile attacks on the UAE. Since 2018, the Houthis had been conducting missile strikes against airports and oil facilities inside Saudi Arabia, and they further increased the frequency of attacks. Saudi Arabia also intensified airstrikes on Sana’a and densely populated areas. In 1 of 2022, a Saudi-led coalition airstrike on a prison facility in Saada governorate killed 91 detainees and injured 226, becoming the deadliest incident for civilians in Yemen in the past 3 years. Due to this escalation between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia/the UAE, 1 of 2022 is estimated to have been the deadliest month for civilians in Yemen since the conflict began in 2015 overall.

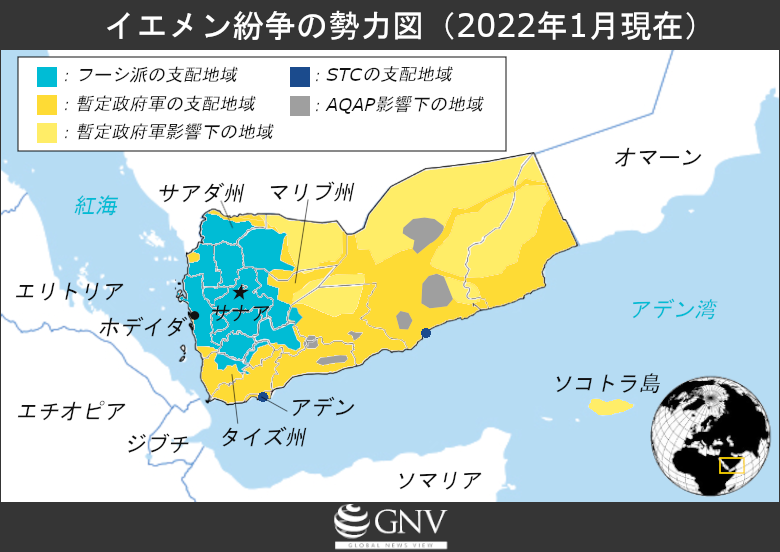

Map of forces in the Yemen conflict (as of January 2022) (based on Al Jazeera data)

Here it is important to note the asymmetry between Houthi attacks and those of the interim government/Saudi-led coalition. The coalition led by Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest arms importer, is backed by Western countries, led by the United States, the world’s largest arms exporter, and possesses far greater military power than the Houthis, who have no fighter aircraft. Indeed, Houthi attacks on oil facilities and other targets have been far fewer in number and lower in destructive power, and the coalition has intercepted their missiles and reportedly kept major damage limited.

Multiple actors involved

The conflict is sometimes described as a “proxy war” between Saudi Arabia and Iran because Saudi Arabia backs the interim government while Iran supports the Houthis. However, the ways in which Saudi Arabia and Iran are involved differ greatly, and the participation of many other countries and armed groups gives the conflict a complex structure. Below we look at these actors as well.

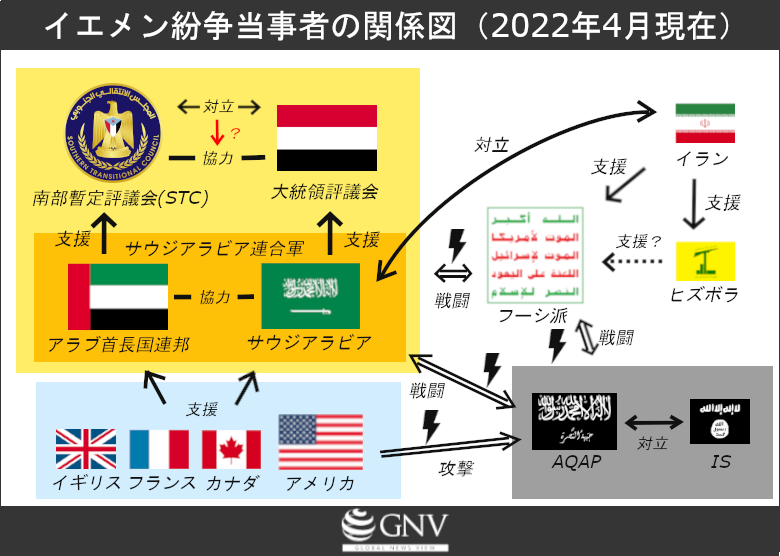

Diagram of relationships among parties to the Yemen conflict (as of April 2022)

First, the forces on the side of the interim government that governed Yemen until 2014: the Yemeni interim government, the Saudi-led coalition, the STC, and Western countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Canada.

The Yemeni interim government, after the Houthis advanced into Sana’a, saw interim President Hadi flee to Saudi Arabia and established its base in the southern city of Aden. It lost influence over anti-Houthi forces and has exercised very little leadership; as a government it has barely functioned.

As of 2015, the Saudi-led coalition included Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco (until 2019), Qatar (until 2017), Sudan, and the UAE, which participated in air and ground operations in Yemen. Somalia also provided its airspace, territorial waters, and military bases to the coalition, and the coalition recruited mercenaries from Colombia—but many countries have since left the coalition.

The Southern Transitional Council (STC) is a force seeking autonomy or independence for South Yemen prior to unification, formed in 2017 after Hadi’s moves in Aden. It has been supported mainly by the UAE and currently controls the southern region around Aden. While it has been at odds with the interim government, the new presidential council that has held presidential authority since 4 of 2022 has stronger influence over anti-Houthi forces than former interim President Hadi, and relations may improve going forward.

The United States provides technical assistance, arms sales, and intelligence, thereby supporting the Saudi-led coalition from behind. Most of the weapons imported by Saudi Arabia are from the United States, and in one way or another the U.S. military has been involved in a significant portion of the strikes in air operations led by Saudi Arabia—such as target selection and aircraft maintenance.

Other Western countries, such as the United Kingdom and France, have also supplied weapons to the Saudi-led coalition to reap economic benefits from the arms trade. The UK and France account for 9% and 4% respectively of Saudi Arabia’s imports after the United States, and Canada is also said to be complicit in the conflict through arms exports.

Flag bearing the Houthi slogan (Photo: Abdullah Sarhan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]) (※2)

Next, the forces opposing the interim government and Saudi-led coalition include the Houthis, Iran, and Hezbollah.

The Houthis began an anti-government campaign in 2004 and now control northern Yemen centered on the capital, Sana’a.

Iran is said to have repeatedly provided economic and military support to the Houthis. Unlike Saudi and UAE air campaigns, it is not believed to be directly participating in operations or openly endorsing Houthi attacks, but rather is thought to be limiting itself to indirect assistance only.

Hezbollah is an organization formed in 1982 after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, and has received funding and weapons from Iran since its inception. Saudi Arabia alleges Hezbollah is involved on the Houthi side in the Yemen conflict, but the extent of Hezbollah’s involvement in Yemen has not been clarified.

Finally, there are other armed groups that do not fit neatly into either of the two camps above.

AQAP is al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. It has expanded its influence mainly in the east, opposes both the interim government side and the Houthis, and has carried out many terrorist attacks across Yemen; in response, the United States has conducted drone and other strikes.

IS is an extremist group that was based in Iraq and Syria. IS has also carried out attacks nationwide, similarly to AQAP. It is said that IS has been much smaller in scale and influence than AQAP and is believed to be in conflict with AQAP.

Humanitarian crisis

The Yemen conflict has produced not only combatant casualties but also many civilian victims, to the point that it is called “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.” The total estimated deaths, direct and indirect, reached 377,000 by the end of 2021, and 4.2 million people became displaced. The types of harm caused by conflict are not uniform. Here, we divide the causes of humanitarian harm into direct violence and indirect, non-violent causes.

A refugee camp in Lahij governorate in southwestern Yemen (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] )

Direct causes are those stemming from conflict-related violence, which has claimed many civilian victims as well as combatants. Both the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition bear responsibility for the damage, but Saudi airstrikes are said to have caused the most severe harm. According to data from 2015 through 3 of 2022, there have been more than 25,000 documented airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, and nearly 20,000 civilians have been killed or injured. Cluster munitions, which scatter small bomblets over a wide area, cause severe harm to civilians; in 2015 and 2016, 91% of cluster munition casualties were civilians, injured not only at the time of attack but also by unexploded ordnance.

More troubling in this conflict, however, are the indirect causes. The vast majority of the estimated 377,000 deaths by the end of 2021 were due to indirect causes such as shortages of food, water, and medical services, which have caused vast harm. The most vulnerable to these causes of death are young children, who are particularly susceptible to undernutrition; in 2021, among children under 5, one child every 9 minutes died because of this conflict.

In 2022, approximately 20.7 million people needed humanitarian assistance, which is roughly equivalent to for every 3 people, 2 in Yemen. In addition, more than half of the population—17.4 million people—are experiencing food insecurity. Since its emergence in 2016, cholera—an intestinal bacterial infection that causes acute watery diarrhea and vomiting—has affected many people. From 10 of 2016 to 12 of 2020, there were more than 2.5 million suspected cases of cholera reported, the largest number in the world since the World Health Organization began cholera recordkeeping in 1949.

A doctor examines a child’s nutritional status (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The humanitarian crisis from indirect causes has been made more severe by the blockade of ports and cities by parties to the conflict, causing shortages of food, medical supplies, aid, and fuel, and driving up the prices of essentials. Since 2015, the Saudi-led coalition has used its military to block flights from landing and ships from docking in Yemen, ostensibly to prevent weapons smuggling to the Houthis. The fuel blockade at Hodeidah port has been particularly problematic; the port had handled more than half of Yemen’s commercial fuel. Airstrikes on energy production areas also made access impossible and caused fuel shortages. Fuel shortages not only hinder the transport of medical and aid supplies; they also prevent the use of generators, impairing hospital operations and access to clean water, and leading to increases in diseases such as cholera and acute watery diarrhea. In addition to the fourth wave of COVID-19, increases in preventable diseases like diphtheria have collapsed an already fragile healthcare system.

Recent global developments have also greatly affected the humanitarian crisis. Rising global food prices combined with funding shortfalls have forced the World Food Programme (WFP) to cut the food aid it can deliver. In addition, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent fuel and food prices soaring. Ukraine accounted for 31% of Yemen’s wheat imports, and as of 3 of 2022 prices were about 7 times higher than in 2015 on average. Funding from other countries has also been limited: as of July 2022, only 27% of the amount requested for Yemen through the United Nations had been raised.

Achieving a truce

After bringing about the tragic humanitarian toll described above since 2015, on 4–1–2022 UN Special Envoy for Yemen Hans Grundberg announced that a two-month truce in the conflict had been secured, which took effect at 7 p.m. Yemen time on 4–2. The UN had previously tried to mediate a truce, but agreement had not been reached due to opposition from the interim government and the Houthis.

Among the factors leading to the truce was that both sides had become exhausted to the point that they could benefit from it. A series of escalations between the Houthis and the interim government side since 2022 led to a military stalemate. When a conflict is stalemated, there is no pressure to tilt the terms of a truce in favor of one side. The economic impact on both territories from soaring global commodity prices is also considered one factor.

Since the truce began, civilian deaths have fallen significantly and the situation has improved. Because the truce required all parties to cease military operations, the number of civilian casualties in Yemen fell from 456 in the two months before the truce to 265 in the two months after—a 41% decrease. Airstrikes, which accounted for most attacks affecting civilian infrastructure in the three months before the truce in 2022, ceased, leading to a substantial reduction in impacts on civilian infrastructure since the truce began.

The easing of the fuel embargo on Hodeidah port imposed by Saudi Arabia also helped, with 18 fuel shipments permitted during the two-month truce period. As a result, food and clothing were delivered to Hodeidah port.

Furthermore, commercial flights from Sana’a airport—banned for nearly 6 years—resumed, with 2 weekly flights to Jordan and Egypt. The interim government/Saudi-led coalition allowed the use of passports issued by Houthi authorities in Sana’a for travel. With safer means of movement, access to essentials and medical services becomes easier.

And from June 2, it was decided to extend the truce agreed in April. Given the improvements noted above, extending the truce is expected to bring further gains.

On the other hand, as access has expanded into areas previously off-limits, casualties from landmines and unexploded ordnance increased in the two months after the truce compared with the two months before it. Although hostilities have generally decreased, both sides have repeatedly reported violations of the truce. In Taiz governorate, roads have been blocked since 2016 in areas under Houthi control, and although reopening these roads was among the truce conditions, progress on reopening has yet to be made.

The Yemen conflict as a global issue

As described above, multiple actors with political aims are entangled in the Yemen conflict, and each bears responsibility for the tragic outcomes.

The United States and other Western countries continue military support centered on arms supplies, and even countries that do not supply weapons—such as Japan, which relies on Saudi oil—have been reluctant to strongly criticize or condemn the Saudi-led coalition’s military actions. One reason is that Saudi Arabia’s cooperation is essential to managing global oil prices. Amid this context, U.S. President Joe Biden is visiting Saudi Arabia in 7 of 2022. In light of sanctions on Russia and countering China, Biden is putting focus on stable energy supplies from the Middle East, and given that the United States has long been complicit on the Saudi side of the conflict, it seems unlikely that Washington will exert significant pressure on Saudi Arabia to resolve the war.

After nearly 7 years, the Yemen conflict has entered a new phase in which improvement on the battlefield can be expected. We should keep a big-picture view and pay attention not only to the status of the truce but also to the actions of multiple actors and the effects of global developments on this conflict.

※1 The term was subsequently extended by one year.

※2 Flag bearing the Houthi slogan — in Arabic it reads “God is great, death to America, death to Israel, curse the Jews, and victory to Islam,” as noted.

Writer: Chika Kamikawa

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

イエメンで働く医師の友達がいます。彼は日本で生まれ両親の交通事故に、より孤児となり海外に、渡り勉強して医師に、なりました。彼は,足を銃で打たれ食事もなく薬だけの生活助けてあげたい気持ち有るが,何も出来ない現状助けて下さい!日本に、帰りたがっています。日本に、帰りちゃんと治療させてあげたい