The Government of Kenya announced that, due to security concerns, it will close by June 30, 2022 the 2 refugee camps in Kenya that were once the largest, Kakuma and Dadaab. Together, 430,000 refugees live there under harsh conditions. It is still unclear what impact the closure of these camps will have on the refugees.

Recently, attention has also focused on refugees generated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As of May 2022, the number of people who have crossed borders from Ukraine is said to exceed 7 million. It is undeniable that they are fleeing life-threatening danger; however, it is also true that compared to other refugees, they are in a relatively more favorable situation. This article explores the realities of refugee camps, which are less frequently covered, and the widening inequalities within them.

Scene from the Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh (Russell Watkins / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

What is a refugee?

How is “refugee” defined in the first place? In the 1950 Statute of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Note1) (UNHCR), the 1951 Refugee Convention, and the 1967 Protocol, “refugees” are defined as people who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, are outside their country and require international protection. However, this definition does not include those displaced by armed conflict, and in practice the number of people treated as “refugees/displaced persons” is greater than this definition. In recent years, in addition to the above (often called “Convention refugees”), there has been recognition of a broader category of “refugees under an expanded definition”, who are also persons of concern to UNHCR. That said, those who are displaced for similar reasons but have not crossed borders—so-called “internally displaced persons” (IDPs)—are not included in that definition. In certain crises, IDPs may also receive support from UNHCR, but many remain without protection.

How many refugees are there in the world today? According to UNHCR, in 2020 there were 82.4 million people forcibly displaced by conflict and persecution worldwide—equivalent to 1 in 100 people. Of these, refugees number about 30.3 million (including 20.7 million under UNHCR’s mandate and 5.7 million under the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) (Note2)), internally displaced persons about 48 million, and asylum-seekers about 4.1 million. As of 2021, the top 3 countries producing refugees are Syria, Venezuela, and Afghanistan, while the top 3 host countries are Turkey, Colombia, and Uganda (Note 3). As this shows, host countries are often low-income, and the lack of resources frequently hampers the establishment of adequate support systems.

So where do these 30.3 million refugees live? Those living in what are commonly called refugee camps are a minority—about 22%. The remaining 78% live with acquaintances or sponsors, rent houses or apartments on their own, occupy vacant or unused buildings, or pitch tents in open areas. Below, we take a closer look at what refugee camps—home to more than roughly 6 million people by simple calculation—are like.

Refugee camps and their challenges

Refugee camps are collective settlements established by host governments or by the UNHCR and other organizations at the request of host governments, and are places where refugees are guaranteed safety and receive assistance with shelter (tents or temporary housing), food, water, clothing, medicine, and daily necessities. Refugee camps are, by design, temporary places of refuge and are not intended for permanent residence; the goal is repatriation when conditions in the home country are safe.

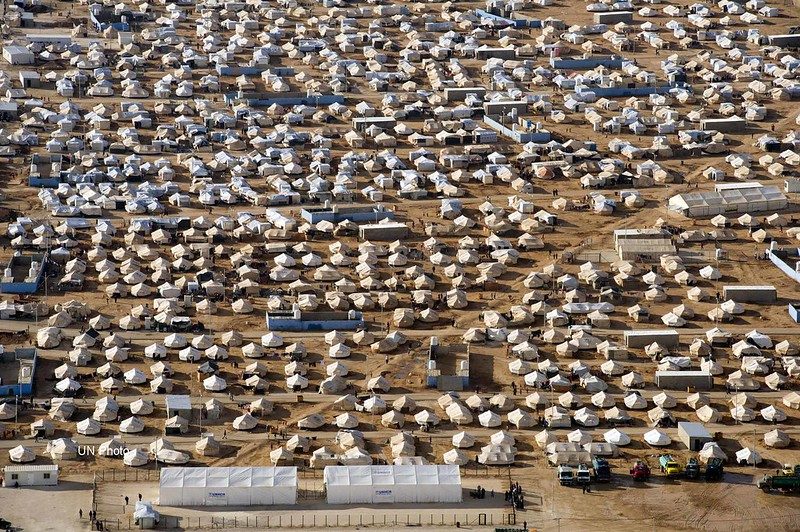

Countless tents lined up in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan (United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Although refugee camps are meant to protect refugees and provide an environment for temporary living, they often fail to fully realize this purpose and in practice face a variety of problems. Below we discuss these issues.

First is the shortage of food and water. This is a persistent problem for most refugee camps and arguably the single biggest factor preventing camps from fulfilling their original purpose. Host countries themselves often lack ample supply, making it hard to secure the quantities needed for refugees. Water in particular may not reach people because local water infrastructure is underdeveloped, causing camp logistics to break down. Moreover, camps are often set up on barren land near borders, making self-sufficiency in food difficult and drinking water hard to secure. There are also limits to the food aid UN agencies can provide. While this has been a chronic issue, in recent years rising food prices due to the situation in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, and climate change have made provision even more difficult.

Next is poor sanitation. Refugee camps are extremely densely populated. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh—home to one of the world’s largest refugee settlements—the population density is about 33,000 people/km², exceeding that of Dhaka, the capital with one of the highest densities globally. High density directly increases the spread of contagious diseases, so refugee camps constantly carry the risk of pandemics of various infections. As noted in the water section above, the lack of developed water infrastructure—poor water and sewage systems—also worsens sanitary conditions. Shortages of sanitation and medical staff and related supplies are further major causes.

Children fetching water at the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan (Mustafa Bader / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Another set of issues arises from prolonged stays in refugee camps. As noted above, camps are intended as “temporary” places of refuge until it is safe to return home. Accordingly, planning typically provides for simple facilities intended for short-term residence. In reality, however, recent studies indicate that the average duration of exile exceeds 20 years, and problems associated with this have become frequent.

First is lack of education. Many camps provide opportunities for schooling. Yet a report finds that, as refugee children age, the gap with global averages widens. While the global average primary school attendance is 91%, among refugees it is 61%; at the secondary level, the world average is 84% versus 23% for refugees. This is the average for all refugees; in low-income countries specifically, it drops to about 9%.

Employment is another issue. The Refugee Convention recognizes the right of registered refugees to engage in wage-earning employment, but in many camps refugee employment is heavily restricted. There are also racial restrictions: in Turkey, for example, refugees from Europe in camps may work, while non-Europeans face major restrictions.

There are also mental health issues. Being forced from one’s home already inflicts severe psychological trauma. Many have lost family members or faced mortal danger themselves. If life in what was thought to be a temporary refuge in a camp drags on, the damage grows: being unable to work and build a career, being unable to provide children with adequate education, and the uncertainty about the future all place heavy burdens on mental health. For example, a doctor serving the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos reported an overwhelming number of psychiatric patients, and one survey found that 1 in 4 children in the camp had considered suicide.

Syrian refugees lining up to cross the border between Austria and Hungary (Mstyslav Chernov / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Examples of refugee camps

Here we explain the realities of refugee camps by looking at major examples in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

First, in Asia, the Kutupalong refugee settlement located in the Cox’s Bazar region of Bangladesh. As noted in the sanitation section above, this agglomeration of camps shelters Rohingya refugees from Myanmar; across 26 camps, about 770,000 refugees live there, more than half of them children. The geography leaves the area highly vulnerable to natural disasters. Each monsoon season, the camps themselves suffer devastating damage, including flooded shelters. In March 2021, a large fire broke out in the settlement, destroying 9,500 shelters and temporarily leaving more than 45,000 people homeless. This illustrates how natural disasters in densely populated areas can cause massive damage at once. The settlement also faces a severe food crisis. As Bangladesh is not a wealthy country, people rely on food from other countries for most of their needs, but such aid cannot cover the vast population of 770,000 refugees.

Next, in Africa, the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. This camp hosts more than 180,000 refugees from 15 countries, including South Sudan and Somalia. The biggest problem is overcrowding, leading to shortages of infrastructure and resources. Water scarcity is particularly severe; some people purchase water traded informally because the water supplied by the camp is insufficient. Meanwhile, as noted at the outset, the Kenyan government has announced the closure of these camps. The government says the reason is that they have become gathering points for armed groups and pose a security threat to surrounding areas, though there is no conclusive evidence. In conjunction with the closure, the Kenyan government has announced options for the affected refugees: 1) voluntary repatriation, 2) alternative stay in camps provided by the East African Community (EAC) (Note 4), 3) naturalization as Kenyan citizens, and 4) promotion of resettlement to third countries. However, this plan does not appear capable of accommodating the 430,000 people in Kakuma and Dadaab combined. Although closure has not yet occurred, we should watch closely what problems emerge if and when it does.

A school in Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp (D. Willetts / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO])

Finally, in the Middle East, the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. Established in 2012, it is the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp. In 2013 the population peaked, with about 200,000 people living in a camp with a capacity of 60,000, making it the 4th largest “city” in Jordan. It remains a large camp of about 80,000 residents. The camp was set up in just nine days to respond to the Syrian conflict, so initially lifelines and housing were not well organized. Illegal employment is a problem: informal jobs that do not comply with Jordanian labor laws, including wage issues and child labor, are widespread. Some employers exploit refugees as cheap labor compared to local Jordanians. Yet given the difficulty of obtaining formal employment, this is a very hard problem to remedy.

Inequalities pervasive in refugee assistance

There is a reality in which, depending on where people are received, their nationality, or their race, some refugees cannot secure even a minimal standard of living. Here we discuss such inequalities in refugee assistance.

Broadly, inequalities in refugee assistance fall into 2 categories: “disparities at the global scale” and “differences in treatment within the same host country.” The former refers to disparities among refugees in different countries, while the latter refers to differences in treatment based on nationality or race among refugees in the same country.

First, the former—“disparities at the global scale.” According to data on emergency humanitarian assistance via the UN, as of June 15, 2022, Ukraine had received 70% of the funding requested by UN agencies, whereas most other countries had generally received less than 30%. As a result, Ukrainian refugees have enjoyed comparatively safe living conditions with access to water, food, and health services secured, while many of the refugees discussed above live day to day without knowing how they will survive tomorrow. Many countries are allocating large budgets to aid for Ukraine, but overall official development assistance (ODA) has not increased dramatically, raising concerns that budgets for other regions are being reduced.

A charity concert in the United States in support of Ukraine (Photo: Alec Wolvec / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

A similar case occurred over 20 years ago with refugees from the conflict in Kosovo, also in Europe. At the same time, conflicts were occurring in countries including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, and Angola. The situation in the DRC was particularly dire, resulting in 1.7 million deaths over two years, while in Kosovo 2,000 people died over two years. Yet, as with Ukraine today, Kosovo—which was widely reported and drew significant attention—received funding equal to or exceeding requirements, while the seven poorest countries, including the DRC, received only 17% to 44% of what was needed.

Next, the latter—“differences in treatment within the same host country.” Even within one country, treatment can differ by refugees’ country of origin or skin color. For example, Poland has accepted the majority of Ukrainian refugees. The Polish deputy interior minister said they are actively promoting placement with host families, unlike previous refugee responses. Yet the Polish government has a past record of refusing refugees from the Middle East and Africa along with Hungary in 2015. A public opinion poll also showed that 75% of Poles oppose accepting refugees from the Middle East and Africa. In contrast, a survey found that 90% believed Ukraine’s refugees should be accepted in Poland, highlighting the disparity.

In Switzerland, an S permit was issued to Ukrainian refugees. The S permit exempts individuals from lengthy asylum procedures, such as case-by-case assessment of reasons for flight, enabling rapid admission. It also confers benefits unavailable to other refugees. This was not issued even during the Syrian crisis, and it allows Ukrainians to receive various advantages.

Japan has historically taken a relatively cold stance toward refugees; in 2021 it recognized only 74 out of 2,413 applicants—less than 1%. Yet it has taken an exceptional stance toward Ukrainians, announcing the swift acceptance of 1,000 refugees. The government also announced robust support after arrival: initial hotel accommodation upon entry, a lump-sum payment upon leaving the hotel, and living expenses. For visas, entry is first on a 90-day visa, with permission to switch to a visa valid for 1 year. This is highly unusual given Japan’s past refugee policy.

There are also cases, apart from Ukraine, where the same country treats refugees differently by nationality—Turkey, for example. Although Turkey has accepted many Syrians, their right to work is heavily restricted. This stems from Turkey’s distinct policy of granting “refugee” status only to people from Europe. As a result, Syrians from a non-European country are treated as “conditional refugees,” and many are forced into informal, low-wage jobs that do not require work permits.

Syrian refugees in Turkey (European Parliament / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]])

Why do these disparities arise?

We have examined the current situation of refugees and these disparities. While support for Ukrainian refugees has reached astonishing levels, many others are forced to live harsh lives due to insufficient aid. Considering these disparities, various possibilities and critiques have been raised. One factor thought to be strongly related is white prioritization in humanitarianism. One commentary notes that such racial discrimination is evident at both the individual and national levels. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus also pointed out, in light of the treatment of Ukrainian refugees, that “the world does not treat black and white lives the same when it comes to emergencies.”

Media coverage is also closely tied to inequality. Constantly sympathetic reporting focused only on Ukraine has brought in large amounts of aid there, while other humanitarian crises receive relatively little coverage and less attention, resulting in a persistent lack of support.

What measures are needed to correct inequalities in refugee assistance, especially in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia? We cannot overlook the reality that some people who have fled persecution are facing fresh persecution and discrimination in the places they sought refuge.

Note 1 UNHCR was established in 1950 after the war to help millions of Europeans forced to flee or who had lost their homes. It was initially planned to complete its work in three years and disband, but more than half a century later it continues to address refugee issues worldwide.

Note 2 UNRWA is a UN agency separate from UNHCR, established in 1949 to respond to the Palestine crisis and support Palestinian refugees. Some argue it became unnecessary after UNHCR was founded, but UNRWA still has jurisdiction over Palestinian refugees.

Note 3 The top 10 countries producing refugees are Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Somalia, the Central African Republic, and Eritrea. The top 10 host countries are Turkey, Colombia, Uganda, Pakistan, Germany, Sudan, Bangladesh, Lebanon, Ethiopia, and Iran.

Note 4 EAC is an intergovernmental regional organization comprising Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, headquartered in Tanzania.

Writer: Yusui Sugita

人口密度の高い難民キャンプでは、コロナの流行も相当なものだったと推測されます。しかし実情は知りません。ここで改めて、コロナ報道で取り上げられる地域にも差があるのだなと感じました。

ウクライナ情勢に対して過敏な反応を示していることは感じていたが、ここにも報道される世界とされない世界とでの格差が存在しているということがよく分かる記事でした。