Since the start of the 21st century, Mongolia’s economy has grown rapidly. In 2011, it was said to be the fastest-growing country in the world, recording about 17% economic growth. A major factor behind this has been the extraction and export of mineral resources. Mongolia’s exports increased from about 6.2 hundred million US dollars in 2003 to, as of 2019, about 76. 1 hundred million US dollars. About 80 percent of those exports are minerals. There are several large mines for copper ore, gold ore, and coal, and mining is also conducted for various other minerals such as silver ore, iron ore, tungsten, uranium, fluorspar, rare earths, and oil. At present, it is no exaggeration to say that mining supports Mongolia’s economy. However, are mineral resources truly making Mongolia prosperous? Behind the boom there are also various problems. Tax avoidance, corruption, and environmental pollution are also negatively affecting the lives of Mongolian people. In this article, we would like to unpack the reality of mining in Mongolia.

Mongolian mining landscape (Photo: bazarsadbayarsaikhan / Pixabay [Pixabay License])

目次

Mongolia’s history and mining

Mongolia is a landlocked country sandwiched between Russia and China. The south is covered by the Gobi Desert, the northwest by cold mountain ranges, and the rest is high plateau. Surrounded mainly by mountains, it is shielded from wind and rain and enjoys about 250 days of sunshine annually. Winters are very long and cold, lasting from November to late April. The population is about 3.22 million, making it one of the countries with the lowest population density in the world. Mongolia has a long history of nomadism, and sheep, goats, and camels are mainly herded.

The Mongol Empire acquired vast territories from the 13th to 14th centuries and ruled much of the Eurasian continent. The empire eventually fragmented and declined. In the 17th century, Mongolia became part of China’s Qing dynasty. Coal mining began in the 1900s. After the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, Mongolia declared independence, and with Russian support achieved independence in 1921. In 1924 it became the socialist state of the Mongolian People’s Republic. During this period, Mongolia’s economy was supported mainly by pastoral nomadism and remained sluggish. Until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, it was a Soviet satellite, heavily dependent on economic, military, and political support. As part of its economic aid, the Soviet Union began joint copper extraction with Mongolia in the 1970s.

After the Soviet collapse, Mongolia transitioned to democracy and a market economy. This spurred investment from abroad into mining. Thanks to foreign investment, Mongolia’s economy, which had relied on pastoralism and agriculture, underwent a major transformation. Since the 1990s, foreign companies have entered, conducting exploration and extraction.

Mine workers collecting coal (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Major mines

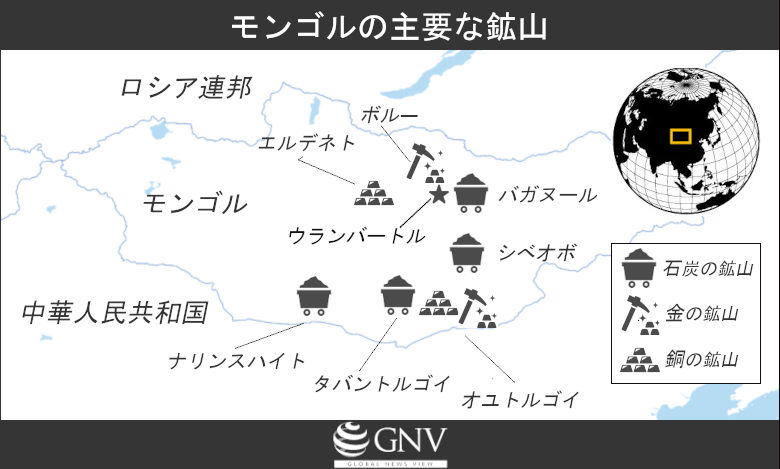

So where and what kind of mining is being conducted today? Below is a summary of the major mines.

The main coal mines are Tavan Tolgoi, Nariin Sukhait, Baganuur, and Shivee-Ovoo. Mining began at the Tavan Tolgoi coal mine in 2006. The deposit is estimated at about 6.4 billion tons, and in the first half of 2018 it exported 6.9 million tons of coal. About 70% of the coking coal exported by Mongolia is produced at Tavan Tolgoi and exported to China. Currently, the mining rights are held by the Tavan Tolgoi joint-stock company owned by the government and private sector, the 100% privately owned Energy Resources LLC, and the 100% state-owned Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi JSC mining rights.

At the Nariin Sukhait coal mine (also known as the Ovoot Tolgoi coal mine), coal extraction began in 2008. The deposit is said to be around 380 million tons. The current holders of the mining rights are Mongolia’s Mongolian Alt LLC and Usukh Zoos LLC, the China–Mongolia joint venture Chinhua MAK Nariin Sukhait LLC, and Canada’s SouthGobi Sands LLC. China is the main export destination, and a railway connecting the mine to the Chinese border was built in 2007.

The Baganuur coal mine has been in operation since 1997. The mining rights are held by Baganuur JSC, with a 75% government and 25% private-sector share. The mine has been developed with funding from Japan’s International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank. In 2020, 4.05 million tons of coal were mined.

The Shivee-Ovoo coal mine has also been operating since 1997, and the mining rights are held by Shivee-Ovoo JSC, Erdenes Mongol LLC, and Eigsol LLC, with shares of 90% government and 10% private sector. The Shivee-Ovoo mine has also been developed with funding from JICA and the World Bank. From 2021, it is planned to mine 300,000 tons of coal annually. There are currently plans to build a coal-fired power plant next to the Shivee-Ovoo mine to use the coal for power generation. Construction is scheduled to start in 2023 and the plant is expected to supply electricity within Mongolia and to China.

Gold is also mined in Mongolia. At the Boroo Gold Mine, extraction began in 2003 by the Canadian company Centerra Gold. Mining continues today, but since 2018 the mining rights have been transferred to Singapore’s OZD Group. From 2004 to 2017, 56.7 tons of gold were mined.

Copper is another major mineral product. In 1978, based on an intergovernmental agreement between Mongolia and the Soviet Union, Erdenet Mining Corporation was established and extraction began at the Erdenet copper mine, which continues to operate today. About 32 million tons of copper ore and 530,000 tons of copper concentrate are mined annually. At the Oyu Tolgoi mine, some of the world’s largest copper and gold deposits have been discovered. In 2011, the multinational Rio Tinto, based in the UK and Australia, began open-pit mining. Underground mining also began in January 2022, with plans to extract up to 500,000 tons of copper ore per year.

In addition to coal, gold, and copper, there are also deposits of fluorspar and uranium. Fluorspar is a mineral used in aluminum smelting and metallurgy, and in 2011 Mongolia was the world’s third-largest producer of fluorspar. In Dornogovi Province, located in the southeast, uranium deposits have been discovered, and the French state-owned Orano mining group and Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation are currently conducting exploratory mining.

Impact on the economy

In 2000, mining accounted for about 10% of GDP, but by 2021 this had increased significantly to about 25%. The share of mining in foreign investment was 44% in 2000, rising to 73% in 2019. From 2016 to 2021, mining accounted for about 70% of Mongolia’s total exports. Mining employs 3.6% of the population, and mine workers and truck drivers who transport mineral products can earn two to three times the Mongolian average income.

Since mining became the main industry in Mongolia, the economy has grown while repeatedly cycling through booms and busts. In 2004, the economy grew by about 10% from the previous year, and in 2011 it reached a record growth rate of 17%, continuing rapid growth until 2015. A major factor was Chinese demand for minerals, but in 2016, as China’s economic growth slowed, Mongolia’s mining growth also declined. The Mongolian currency, the tugrik, fell by about 80% against the US dollar from 2013 to 2017, government bonds increased, and the country fell into a fiscal crisis. In 2017, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved financial support. Even now, Mongolia’s mining sector tends to be easily influenced by China’s economy. As of 2020, over 95% of coal and copper are exported to China.

China’s downturn was not the only reason for the increase in government debt. Another was pre-election largesse. A study comparing public expenditures before (1998–2003) and after (2004–2019) the development of mining found that in the election years of 2008, 2012, and 2016, spending on public investment, welfare, and civil servants’ salaries and pensions increased compared to typical years. In 2016, when the economy was sluggish, it is said that some additional spending was financed by borrowing. If most of the profits from mineral exports are used by the ruling party for election measures, it will be difficult to achieve stable economic development.

An open-pit coal mine in southern Mongolia (Photo: Bankwatch / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Political and economic challenges

Mineral resources are also intertwined with Mongolia’s political and economic issues. First is tax avoidance by foreign companies and others participating in mining projects. For example, in the case of the Oyu Tolgoi mine, Rio Tinto is said to have engaged in tax avoidance by shifting profits to Luxembourg, a tax haven. It took out loans and advanced investments through financial companies based in Luxembourg. Because the interest paid when repaying those loans counts as profit in Luxembourg, favorable treatment allows the company to pay taxes at very low rates. On top of that, it also received incentives within Mongolia, further reducing Rio Tinto’s tax burden. As a result, the tax revenue that the Mongolian government should have received from the Oyu Tolgoi mine has been greatly reduced.

Another problem is lack of government transparency in the mining sector. Information on which companies hold mining rights is disclosed. However, many companies are established specifically for mining projects, and information on who ultimately holds the beneficial ownership of those companies is not made public. It has been pointed out that in order to prevent corruption, it is necessary to disclose exactly who is benefiting from the mines.

This lack of transparency also affects corporate activities. For example, in 2013, 106 mining licenses granted by a government official convicted of corruption were revoked. While many of these licenses may have been improper, it has not been proven that they were actually illegal. If mining licenses are revoked without valid reason, companies that obtained rights through legal channels may have to suspend operations.

Exposing illegal acts and corruption by the government or companies is also dangerous. Activists and journalists who try to make wrongdoing public may face surveillance, threats, or penalties. In 2015, the body of a nature conservationist was found about 2,000 kilometers from her home. Police announced it as a drowning suicide, but involvement by a mining company that had been in conflict with her over wildlife protection has been suspected. Thus, there appears to be a dark side behind Mongolia’s mining industry.

Meeting between Mongolia’s National Mineral Resources Policy Council and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) (Photo: The EITI / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Environmental issues and impacts on citizens’ lives

One of the most serious negative impacts of mining is environmental degradation, with water issues being the most acute. Even before mining development accelerated, Mongolia faced water shortages due to desertification and drought. As a result of climate change and other factors, many lakes and rivers have dried up, and desertification is particularly severe around the Gobi Desert. Moreover, most of Mongolia’s surface water resources are concentrated in the north, making water sources less accessible in the more arid central and southern regions. Therefore, groundwater accounts for about 80% of Mongolia’s freshwater use.

Precious water resources are vital not only to people’s lives but also to pastoralism and mining, leading to competition for water. However, mining uses large amounts of water, for example to extract minerals from ore. There is a plan to transport water via pipeline from rivers in the north to the south, where many mines are located, but high costs and concerns about sustainability mean it is considered unrealistic.

Currently, the Oyu Tolgoi mine in the south uses water from the saline Gunii Khooloi aquifer, which is not suitable for drinking, but it is believed to be affecting the freshwater used by local residents. To draw water from the aquifer, Rio Tinto drilled boreholes around the mine, and due to design flaws in those boreholes, freshwater used by residents is thought to have flowed into the aquifer, causing some local wells to run dry. In addition to aquifer water, river water has also been used for the mine. It is believed that Rio Tinto’s diversion of the nearby Undai River to supply the mine has also contributed to local wells running dry. There are also records of water being drawn directly from the Undai River and trucked to the mine.

Beyond worsening water scarcity, water pollution has been confirmed. Soils around the Oyu Tolgoi mine and the Tavan Tolgoi coal mine have very high arsenic concentrations, leading to water pollution. Arsenic is naturally released into the environment through the weathering, oxidation, and erosion of sulfide minerals. Copper and gold are often found in sulfide deposits. It has been suggested that sulfides left after extracting copper and gold ore at the Oyu Tolgoi mine may not have been properly treated, increasing arsenic levels in soils. Arsenic is also contained in coal. Arsenic in coal mined at Tavan Tolgoi may also be contaminating the soil.

At the Erdenet copper mine, in addition to arsenic, soils and water have been found to be contaminated by mine waste such as copper. Minerals like copper can be carried by wind from the mine, affecting nearby soils and water. A water resource survey around the Shivee-Ovoo coal mine also found mineral concentrations exceeding safety standards set by the Mongolian government and the World Health Organization (WHO). Around the Boroo gold mine, high arsenic and mineral concentrations have also been identified, revealing contamination around various mines.

A herd of camels at a well (Photo: Bankwatch / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Water pollution also harms the lives of residents living near mines. Goats and camels that drink contaminated water have, in some cases, given birth to offspring with congenital abnormalities. Water around uranium deposits is particularly dangerous and also affects humans. Drinking water resources contaminated with uranium can cause kidney disease and other problems. It has also been reported that pregnant women who drank contaminated water gave birth to premature infants and children with disabilities.

Beyond water shortages and pollution, dust generated by mining also affects local residents’ lives. When hundreds of trucks travel unpaved roads, severe dust is kicked up, affecting the health of local people and livestock. Because these roads pass through grazing areas, they also contribute to the degradation of pastureland. Collisions between trucks and livestock are not uncommon. In some cases, expansion of mines has forced people to relocate from lands where they have long lived. For example, residents around the Oyu Tolgoi mine have lost land for grazing. While some compensation is provided upon relocation, the amounts are problematic. In 2012, when relocation of nearby residents was required, people were pressured to accept low levels of compensation based on distance from the mine rather than the size of the pastureland lost.

A father and daughter resettled due to the impacts of the Oyu Tolgoi mine (Photo: Bankwatch / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

On the path to improvement

Amid various environmental and livelihood problems, there are also cases of residents raising their voices. In the early 2000s, the Onggi River Movement began to counter water depletion and pollution caused by gold mining. Because pastoralism and local livelihoods were adversely affected, people were being forced to relocate. However, residents united, appealed to the government that grants mining licenses, and involved the media to publicize mining practices. In 2007, they succeeded in halting operations at 35 of the 37 mining projects around the Onggi River.

There are also residents uniting to protect their rights in response to how mining is conducted at Oyu Tolgoi. A group called Gobi Soil, formed by local residents, took issues surrounding Oyu Tolgoi’s mining rights to court. After four years of litigation against Rio Tinto, in 2017 they reached an agreement thought to reflect residents’ rights. The agreement encourages comprehensive support for local residents, including appropriate compensation, compensation for lost livestock, protection of water resources, and covering school fees for local children. Full implementation of the agreement will take until 2024, but improvements in residents’ lives are anticipated.

As we have seen, while Mongolia’s mines support economic growth, they also face various challenges. Because Mongolia’s mining sector depends on fluctuating demand in China, it remains unstable. Furthermore, tax avoidance, government opacity, and environmental issues raise questions about how much Mongolia’s resources are truly benefiting its people. However, by raising their voices and continuing to fight for their environment and livelihoods, residents can improve the situation. One can only hope that mining will lead to prosperity rather than calamity.

Writer: Namie Wilson

Graphics: Takumi Kuriyama

普段まず報道されないモンゴルの事情を紹介いただきありがとうございました。鉱物資源をめぐる光と闇の部分はどこの地域でも同様に発生するものですね。経済的に豊かになること=幸福なのか?ということも改めて考えさせられる記事でした。

モンゴルにおける鉱山の功罪について解説されており、大変勉強になりました。

日本のJICAや三菱も権益を持つ石炭やウランの鉱山。

鉱物採掘をめぐる汚職や環境破壊と聞くと、どうも遠いように感じてしまいます。

ですが、回り回って日本の私の生活に関係していると思うと、自分には何ができるのか?と問われる記事でした。

直接にできることは何もありませんが、関心を持ってフォローしたいと思います。

大変重要な記事をありがとうございました。