In 8/2021, the Anti-Human Trafficking Bureau of the Nepal Police arrested most-wanted suspect Sabitri Devi Maraha on suspicion of trafficking as many as 25 women abroad. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg. Human trafficking occurs around the world, but Nepal is regarded as one of the “most profitable human trafficking business markets,” and trafficking takes place daily. Since 2020, the spread of COVID-19 has further expanded the damage. Why is human trafficking so rampant in Nepal? This article looks at its background and efforts toward solutions.

Human trafficking (image) (Photo: Imagens Evangélicas / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

What is human trafficking

Human trafficking is a serious crime and one of the worst human rights violations. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), it is defined as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons and the imposition of labor or enslavement, through the use of force, violence, threats, abduction, fraud, or by taking advantage of a position of vulnerability, for the purpose of exploiting people in vulnerable positions.” In other words, human trafficking not only treats people as if they were objects to be “bought and sold,” but also includes enslaving those who have been sold thereafter (※1). Slavery systems, including human trafficking, are recognized as serious human rights violations under various instruments including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

There are many forms of exploitation. They include forced labor in factories, fisheries, and construction; domestic servitude that forces people to do household work; as well as child soldiers, organ removal, forced marriage, and more. Among these, sexual exploitation is the most prevalent.

Sexual exploitation refers to forcing prostitution, pornography, stripping, and similar acts, with girls and adult women being the main victims. Because only a small fraction of cases are uncovered regardless of the form of exploitation, much remains opaque and it is difficult to grasp the reality accurately. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation accounts for about 50% of cases. In addition to being a grave violation of one’s will and rights, sexual exploitation carries very high risks of assault by buyers or brothel clients, sexually transmitted infections from sexual acts in unsanitary conditions, and unwanted pregnancies. It also poses risks of mental disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

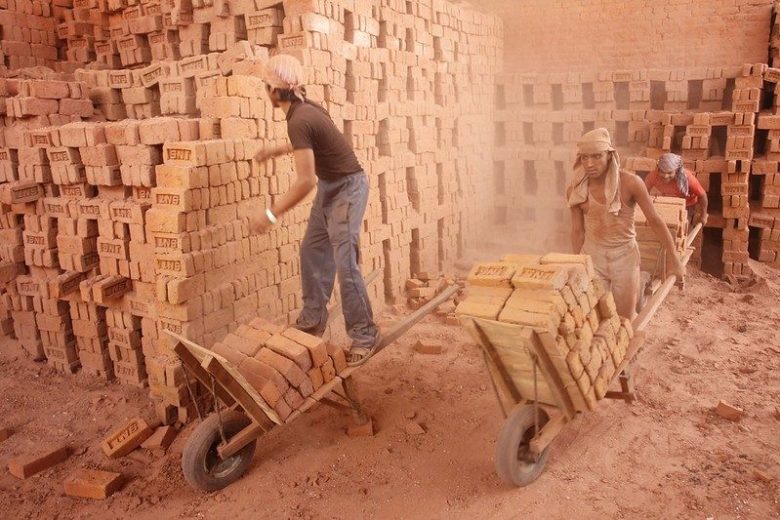

Harsh labor (image) (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Why, then, is human trafficking taking place across so many countries? The main cause is extreme poverty. In impoverished regions, unemployment is high, and many people have minimal and unstable income. Traffickers—so-called “brokers”—target these areas and approach people in economic distress with promises like “We can introduce you to a good job,” or “Life will be easier if you move to the city.” Some are sold to repay debts and become bonded laborers. In families struggling to make ends meet, parents may even send their children away, hoping they can live a better life than they currently have. In many cases, they fall victim without realizing it is trafficking. However, there are also households that knowingly sell their children out of necessity to obtain living expenses.

This “human trafficking business” has accelerated with globalization and now often crosses borders. It is said to be the third most profitable criminal activity after drug and arms trafficking, generating some US$150 billion annually. Human trafficking occurs in countries of both high and low income, but Nepal is considered one of the “most profitable markets.”

The “evil hand” of human trafficking gripping Nepal

Nepal is a small South Asian country bordering India and China, with a population of 29.7 million. Located in the heart of the Himalayas, it is a mountainous country with several peaks over 8,000 meters. About 1.4 million people live in the capital, Kathmandu, while most others live in mountain villages. The main industry is agriculture, which accounts for 34% of GDP, and an estimated 68% of the population is engaged in it.

Many Nepalis also work abroad as migrant laborers. As of 2019, around 3.5 million people—about 14% of the population—were working overseas for employment. Data from the same year shows that about 50% of all Nepali households had at least one family member working as a migrant laborer or had such experience in the past data. The Nepali economy is heavily dependent on remittances from such workers: in 2020, remittance inflows amounted to about US$8.1 billion, roughly 24% of GDP.

Nepal faces severe poverty. The share of people living below the “ethical poverty line” (US$7.4 per day) (※2), which indicates whether minimum needs such as food, clothing, and shelter are met, is 83%. In other words, the vast majority of Nepalis are not achieving a minimum standard of living. On the Human Development Index, which measures development across health, education, and income, Nepal ranked a very low 142nd out of 189 countries as of 2020.

As noted above, human trafficking is rampant in Nepal. According to the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal, there were approximately 35,000 reported victims in 2018 alone. The destinations of victims are diverse, including within Nepal, India, Malaysia, the Middle East, and parts of Sub-Saharan Africa such as Kenya. The main purposes of trafficking in Nepal include sexual exploitation, forced labor, and organ removal.

As with global trends, sexual exploitation is the most prevalent in Nepal, with about 70% of trafficking victims being girls or adult women. Of the roughly 35,000 victims in 2018, at least 20,000 were confirmed to be women. This is only a fraction of the reality, and the true number is believed to be far higher. Many cases involve transport from Nepal to India; data suggests that 54 girls and adult women are sold into India every day.

Women sold to brothels in Nepal or abroad are sometimes forced to serve dozens of clients a day. The number of HIV and other STIs is high, and there are brothels where refusal of the owner’s or customers’ demands results in severe violence. Many brothels are in collusion with mafia and other gangs, meaning victims are under constant surveillance and escape is extremely difficult. In some cases, the brothel owner has assumed the victim’s debt, and girls forced to work as bonded laborers cannot escape until repayment is complete—a grim reality. Many Nepali women remain in dire brothel conditions even today. Nor are the victims only women: about 30% are boys and adult men, who also suffer sexual exploitation and child sexual abuse.

Within Nepal, there are also many cases of domestic servitude and forced labor. Examples include factory work, mining, labor in brick kilns, and embroidery/textile work.

A Nepali girl caring for goats (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Why does human trafficking occur in Nepal?

Why has trafficking grown so widespread in Nepal? Internally, there is the extreme poverty mentioned earlier. Practices such as the caste system (※3) also contribute to inequality. The blow was compounded by the 2015 Nepal earthquake. The magnitude 7.8 quake killed about 9,000 people and affected 5.6 million. It severely impacted already fragile infrastructure and deepened poverty. In fact, the number of Nepali trafficking victims rescued near the Nepal–India border rose from 33 in 2014 (pre-quake) to 336 in 2015, 501 in 2016, and 607 in 2017.

Another internal factor is the vulnerability of women’s status. In Nepal, men tend to receive priority in education, employment, and training across various fields, while women’s social status remains very low. The Nepali Constitution lacks provisions to protect women such as equal pay for equal work; discrimination and violence persist. Practices such as the dowry system (※4) and patriarchy remain deeply rooted and reinforce gender discrimination. As a result, many women are unable to secure stable employment. In such circumstances, Nepali women often wish to escape and find work, making them vulnerable to brokers’ deceit.

There is also the grim reality that 40% of women rescued from brothels do not receive support for rehabilitation and reintegration, are shunned by family and communities, and are forced to return to prostitution. Furthermore, children born to women trafficked for sexual exploitation are said to face a high risk of becoming victims of child abuse and violence, increasing the difficulty adult women and girls in Nepal have in escaping this vicious cycle.

Damage from the Nepal earthquake (Photo: United Nations Development Programme / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Now, consider external factors. One is the low “value,” i.e., price, assigned in the trafficking “market.” The precise amounts for which victims are traded globally are unclear and said to vary by nationality and age, but some researchers estimate a global average price of around US$90. Even that is low, but in Nepal there have been cases where people were traded for as little as US$4. This cheap pricing is one reason Nepalis are targeted.

Another reason Nepalis—especially to India—are trafficked is the disparity between Nepal and India, which also helps keep the “price” of Nepalis low. In 2019, Nepal’s per capita GDP was US$1,194, compared to India’s US$2,100—a stark difference. Nepal is also heavily economically dependent on India. According to an economic survey (2018–19), India accounts for 64% of Nepal’s total trade, and nearly 100% of petroleum supplies come from India. The Nepali rupee is also pegged to the Indian rupee. Moreover, beyond trafficking, more than 520,000 people a year cross into India simply to seek work. In this sense, it is no exaggeration to say Nepal’s economy cannot function without India. As long as this disparity and dependence persist, people will continue to entrust themselves to brokers in hopes of employment.

Furthermore, the open border policy between Nepal and India is another factor making the Nepal–India corridor one of the most frequently used trafficking routes. The open border allows citizens of both countries to cross without visas or passports; such a border is known as an open border. No immigration procedures are required, and movement is unrestricted. This was established under the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship with the aim of granting equal rights to citizens of both countries. While this open border policy enables citizens of either country to own property, work, and live in the other, it also provides fertile ground for trafficking and the smuggling of drugs and weapons, and has even allowed terrorists to cross borders.

People traveling abroad for work (Photo: International Labour Organization ILO / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Destinations for trafficked Nepalis are not limited to India. However, regardless of the destination country, India is often used as a transit point. Why? The reason lies in Nepal’s own regulations. Nepal imposes strict restrictions on women’s overseas employment. For instance, women under 40 who wish to work in Gulf or African countries must obtain permission from a guardian and local authorities—among other limitations. These restrictions make it difficult to traffic women directly from Nepal to other countries. As a workaround, India—outside the scope of these regulations thanks to the open border policy—is used as a route.

Another reason Nepalis are trafficked, particularly to India, is demand within India. The most prominent demands are for sexual services and organs. Demand for Nepali women in Indian brothels is said to be high, partly due to stereotypes about Nepali women. In Indian brothels, stereotypes about features such as skin color have spread and contributed to this demand. In fact, members of the indigenous Tamang people of Nepal have been referred to with discriminatory expressions such as “a very popular product” in brothels.

Meanwhile, demand for organs is also particular to India. India conducts living-donor kidney transplants on the world’s second-largest scale after the United States, and demand for organs—especially kidneys—is significant, with an estimated 220,000 people in need of kidney transplantation. As a result, trafficking for organ removal is conspicuous. In this way, multiple factors—Nepal’s internal conditions and India’s background—combine to make Nepalis prey to trafficking.

Efforts toward solutions and remaining challenges

Are there moves toward resolving this issue? First, consider the Nepali government’s efforts. The government has signed various treaties toward solutions. Nepal has signed and ratified 11 different treaties on women’s rights and health, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) ratified in 1991. Beyond treaties, laws have also been enacted. Under pressure from domestic and international NGOs, Nepal enacted the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act (HTTCA) in 2007, criminalizing human trafficking and mandating that the government establish rehabilitation centers and a fund for victims. Indeed, rehabilitation centers have been established in districts including Kathmandu, Jhapa, and Chitwan today.

Unfortunately, the effects of treaties and laws have been limited for three reasons. First is weak enforceability. For example, the definition of crimes under the HTTCA is narrow. While it prohibits the “buying and selling” of persons and slavery domestically and across borders, it does not prohibit the harboring or transport of persons for the purpose of forced labor. This differs significantly from the UNICEF definition mentioned earlier. Legal frameworks remain insufficient, weakening enforcement.

Police officers at the border (Photo: Bo Jayatilaka / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The second reason is that enforcement cannot keep up. Contributing factors include the sheer volume of cases; limited budgets and time for police investigations; and a shortage of investigators trained to handle trafficking—among other systemic problems. Staffing is particularly serious: while the Nepal Police conduct checkpoints along the Nepal–India border, it is impossible to patrol the entire roughly 1,770 km border daily. Since 2020, lockdowns related to COVID-19 have further delayed enforcement by closing courts for three months and making it harder to obtain statements and testimony due to movement restrictions. Brokers also maintain extensive global networks and transact rapidly online, making tracing difficult and identification challenging. Advances in technology have diversified methods of sale and transport, further complicating detection.

Third, victims often do not report the crime. In many cases, women subjected to sexual violence remain silent. Under Nepal’s patriarchal society, deeply ingrained beliefs and cultural practices are widespread; many families of victims consider reporting sexual trafficking a shame and refuse to go public. In some cases, brokers silence families with hush money; impoverished households may accept such bribes. Lack of knowledge about trafficking also hinders reporting. Education remains inadequate, especially in rural areas, and only 35% of the population has internet access, making information gathering difficult. Many people therefore do not even know they have the right to report. Although the government conducts awareness campaigns, their impact is limited; some officials and police are reportedly unaware of laws such as the HTTCA itself.

Thus, in Nepal, weak enforcement has created a vicious cycle that further accelerates trafficking. While the government has taken steps to eliminate trafficking, they remain inadequate and greater efforts will be needed going forward.

On the other hand, NGOs are working diligently on this issue. For example, Maiti Nepal conducts its own checkpoints near the border and has prevented the trafficking of 1,000–3,000 women and girls each year. It also provides victim protection, legal support, vocational training, and literacy education. Many other organizations, such as the Rescue Foundation, work across borders on trafficking and carry out rescue and support activities. Thanks in part to these NGOs, nearly 1,000 victims are rescued from India each year. However, with tens of thousands of people said to cross the Nepal–India border daily, it remains extremely difficult to find and rescue them all.

A Nepali woman from a debt-bonded family receiving education (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

No clear way forward yet

This article has examined the background of human trafficking in Nepal. First and foremost, what is needed for a solution is institutional reform by the government and police. As noted, enforcement is not keeping pace, making Nepal a hotbed of trafficking. This vicious cycle is a key factor impeding solutions. Rescuing victims and providing rehabilitation are of course also vital and must be expanded, but without simultaneous improvements in government and police systems, eradicating human trafficking will be impossible.

Meanwhile, there is a growing movement in recent years to lift restrictions on Nepali women’s overseas employment. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has deemed these restrictions discriminatory and an impediment to women’s international mobility, and since 2018 has called for their repeal. Would removing such restrictions reduce trafficking? While it could encourage women’s proactive participation abroad, it may also facilitate trafficking without transit through India. The solution will not be straightforward.

Above all, to fundamentally resolve trafficking in Nepal, it is essential to tackle poverty and inequality. However, Nepal still suffers from inadequate infrastructure and deeply rooted historical and cultural practices such as the caste system and patriarchy. There are also issues of massive power imbalances with other countries and unfair trade. With so many factors intricately intertwined, the reality is that solutions will not come easily.

In short, there is still no visible path to resolving Nepal’s serious trafficking problem. NGOs are stretched thin with rescues and support. Will the day come when light breaks through this issue? As fellow human beings living today, we must continue to watch its trajectory closely.

※1 〈Note〉 Expressions such as “buy and sell” and “sold” are not appropriate when referring to people. Because this article frequently uses such expressions, for readability we omit parentheses for all such instances hereafter.

※2 At GNV, we use the ethical poverty line (US$7.4 per day) rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line (US$1.90 per day). For details, see the GNV article “How should we interpret the world’s poverty situation?”.

※3 A South Asian status system. Hindus are divided into four classes—Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra—and occupations and marriage partners are determined based on these classes. Although Nepal’s constitution now prohibits caste-based discrimination, such discrimination remains deeply entrenched.

※4 A system in which the bride’s family pays a dowry to the groom and his family at marriage. Common in South Asian countries including India. If a dowry cannot be paid, women may be beaten or, in the worst cases, killed. Although prohibited by law in Nepal, poor enforcement allows the harmful practice to continue.

Writer: Kyoka Maeda

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

人身売買が現在でもこんなに大規模に行われていることに衝撃を受けました。その背景には、単なる制度上の問題だけではなく、文化的な差別や貧困に関する問題も多く存在していて、多方面から問題解決に取り組むことが必要であることがわかりました。

自分とは遠い話だと思ってしまいがちですが、自分が使っている製品の向こう側には「売られて」働かざるを得ない人がいるかもしれない、という意識を忘れないようにしたいと思います。

まさに今この瞬間でさえも、自分と同じような年齢の人がどこかで売買されているのかと思うと、ちょっと言葉が出ない。

このような問題があることはもちろん知ってはいたが、どこか他人事というか、絵空事のように思っていた。恵まれた環境で育ち生きてきた自分にとって、この記事はとても衝撃的だった。人間が「モノ」のように扱われることに心底恐ろしさを感じた。また同時にもっともっとこの問題について報道されるべきだとも感じた。何が出来るわけではないが、とにかく「知る」ことがとても大切だと思った。

とても低い金額で人身売買されている事実を知り、衝撃を受けました。この事実がもっと世界に知られ、改善されることを願います。

日本で生まれ育った自分にはちょっと信じられないくらい、あまりにも辛い記事であった。同じ世界の同じ人間なのに、生まれ落ちた国の違いや環境により簡単に犯罪に巻き込まれ、人権などまるでない奴隷となってしまう。またそのことに自身で気付かないまま生涯を終えるのだ。そんなことは決して許されない。このような犯罪を一刻も早くなくすためにはどうすればいいのか、答えは簡単ではないだろうが、決して他人事だと知らんぷりして生きていくような社会であってはならないとこの記事を読み感じた。

読んでいてとても心が痛く苦しくなった。

ネパールだけでなく世界中で人身売買が行われているという。日本でももしかしたらあるのかもしれない。

何事も需要と供給だ。求める人がいるなら今後も人身売買はなくならないだろう。同じ人間としてただただ悲しい。

人身売買!小説の中だけの犯罪だと思っていたが、今現在も世界中で当たり前のように横行しているとは驚いた。それだけ報道されていないということなのだろう。我々は報道からでしか海外の情報を得る手段がない。重大な犯罪は国を跨いで行われているのだから、世界で共有してこそ解決に繋げられるのではないだろうか。

自分という存在が軽視され他国に売られていき、ひどい扱いを受ける。貧困が生んだ最大の悲劇である。もっともっと多くの人がこの事を「知る」ことが大切だと思うし、それが解決への第一歩になると思う。

ネパール人の就学生アルバイトが働きにきてますが、

非常にレベルの低い人が多いです。

就学生なのだから、もう少し仕事の理解があっても良い

と思いますが、1度教えて、2〜3日経って同じ仕事を

させるとすでにすっかり仕事の手順を忘れています。

仕事の精度と言ってよいのかどうかわかりませんが、

仕事の正確さがぜんぜん足りません。

少し作業をすると、すぐ休憩したがる。

作業に文句が多く、正確に配置しない。

何をさせても雑。

こんな風に適当にしか仕事をしない人たちは、

適当な低い境遇に置かれても仕方がないだろうと

思います。