In January 2021, the American business magazine Forbes Magazine (Forbes Magazine) announced that it was removing Isabel dos Santos, formerly the richest woman in Africa, from its list of Africa’s wealthiest people. She is the daughter of Angola’s former president, José Eduardo dos Santos. Dos Santos served as Angola’s president for nearly 40 years, until 2017. Under his rule, the dos Santos family controlled Angola’s resources and wealth, so the rise and fall of the family, including Isabel, has been closely tied to his political position and Angola’s political landscape.

Now that roughly four decades of the dos Santos family’s dominance have ended, what is the situation in Angola? In this article, we will explain recent political and economic changes in Angola.

Isabel dos Santos (Photo: Nuno Coimbra / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

About Angola’s history

Angola is located in the southwestern part of the Atlantic coast of the African continent, between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Namibia. It has been profoundly shaped by the transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Americas between the 16th century and the mid-19th century, and by Portuguese colonial rule from 1575 to 1975. Before colonial rule, Angola consisted of numerous polities such as kingdoms, made up of peoples with different ethnicities and identities. The subsequent colonial system drew today’s borders and has influenced political, economic, and cultural practices as well as language and religion.

After a long war from 1961 to 1974, Angola achieved independence at a great cost in lives. The war included independence movements against Portugal by three organizations. The first was the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola: MPLA), established in 1956 through the union of the Angolan Communist Party and a united front party for Africans. The MPLA was based in Luanda, the capital of Angola. The second was the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola: UNITA), a rural guerrilla group that drew global attention in the mid-1960s for launching the first armed attacks against Portuguese colonial rule. UNITA was composed mainly of the Ovimbundu people, and its base of operations was in the diamond-rich northeastern part of Angola. The third was the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola: FNLA). The FNLA was formed in 1956 as the Union of the Peoples of Northern Angola (União dos Povos do Norte de Angola: UPNA) and later changed its name to FNLA. Many of its members were refugees.

By the 1960s, most European countries had withdrawn from colonial rule in Africa. However, Portugal, under Salazar’s dictatorship, suppressed African independence movements by force and continued its colonial rule until Salazar fell in 1974. Angola finally won independence in 1975, and the MPLA, UNITA, and FNLA concluded the Alvor Agreement with Portugal to form a single government. Because these organizations were hostile to each other and had political differences, war broke out over which organization would seize power. As a result, the MPLA won control of the capital and the central government, while UNITA and the FNLA continued to exist as opposing forces. The hostility among the three organizations was the result of social, ethnic, and ideological divisions spurred in part by the colonial system. In particular, ideological differences were heavily influenced by the efforts of the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War to expand their influence in African countries, including Angola. The countries supporting the MPLA, UNITA, and the FNLA were adversaries within the Cold War framework. For example, the Soviet Union and Cuba supported the MPLA, while the United States and apartheid South Africa supported UNITA. The FNLA, which later declined politically and militarily, received support from the United States and some from China. In addition to U.S. and Soviet military aid, South Africa and Cuba also deployed their own troops.

In 1992, a peace agreement between UNITA and the MPLA was brokered by the United Nations. The agreement included holding general elections in which José Eduardo dos Santos of the MPLA and Jonas Savimbi of UNITA would be candidates. Dos Santos won the election, but because UNITA did not accept the result, Angola slid back into conflict. The fighting continued until 2002, when UNITA was defeated militarily and Savimbi was killed.

Buildings destroyed by conflict (Photo: Nathan Holland / Shutterstock.com)

Beyond these conflicts, Angola has also suffered from inequality and extreme poverty. Despite being one of the African countries most blessed with natural resources such as oil and diamonds, most of this wealth was controlled by a small political and economic elite, and the general population did not benefit.

Under the dos Santos administration

Recent Angolan history cannot be told without José Eduardo dos Santos, who ruled Angola for 38 years until 2017. A charismatic figure, he fought for Angola’s independence alongside Agostinho Neto, a founder of the MPLA. As president, dos Santos had constitutional powers that allowed him to control both the government and the party, including appointing the parliamentary party leader, and he also wielded judicial power by appointing prosecutors and Supreme Court judges. He repressed political opponents and instilled fear in civil society to exert total control.

Beyond constitutional authority, dos Santos also retained the right to manage the nation’s resources, including oil, diamonds, and all state-owned companies. He privatized much of the country’s resources and distributed them so that his inner circle could profit.

This system of rule led to a situation in which ordinary citizens suffered from hunger and extreme poverty while dos Santos and his cronies controlled most of the nation’s wealth. They ran numerous companies and amassed vast riches. In fact, most of Angola’s major state-owned enterprises were managed by dos Santos’s allies. This kind of clientelism (※1) and nepotism (※2) was a major hallmark of the dos Santos regime. For example, Sonangol, the state oil company whose sales accounted for one-third of Angola’s GDP and whose exports accounted for 90% of the national total (Sonangol), was directly managed by dos Santos’s family and the power elite of his party.

Thus, over his long rule, dos Santos built a vast business empire centered on his family. According to rankings published by Africa Trendy, as of 2020 he was still considered the richest person in Angola, with assets totaling US$20 billion.

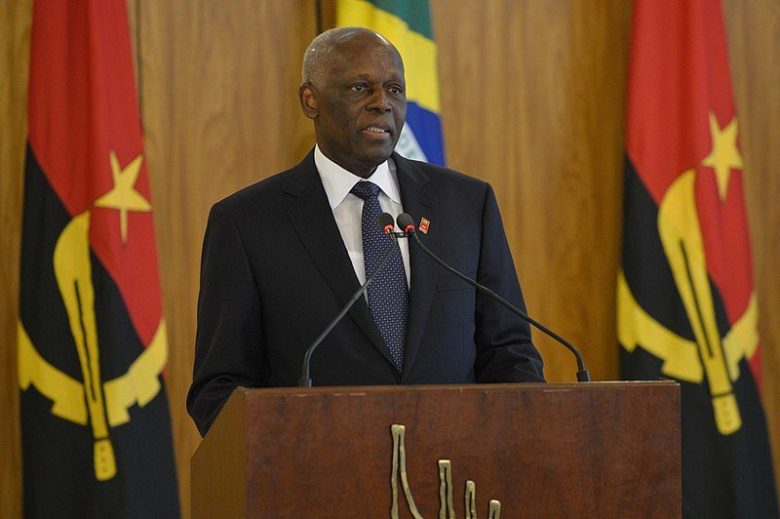

Former President José Eduardo dos Santos (Photo: Fabio Rodrigues Pozzebom/Agência Brasil / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 3.0 BR])

Dos Santos’s children also wielded power and amassed great wealth. His daughter Isabel, mentioned at the beginning, built numerous companies in different sectors across more than 40 countries. These companies won public contracts and engaged in consulting and lending. On the strength of these businesses, Isabel became Africa’s richest woman. From 2016 to 2017, she also served as an executive at Sonangol, Angola’s state oil company.

Dos Santos’s son, José Filomeno (nicknamed “Zenú”), was another who amassed great wealth. With experience in banking and finance, he was appointed in 2013 to manage a state sovereign wealth fund. Established in 2011, the fund was intended to stabilize the economy by safeguarding investments, oil revenues, mineral shares, and other state income in preparation for financial crises. He abused this power and was involved in money laundering and other bribery schemes.

Another daughter, Welwitschia, has overseen major media outlets and advertising agencies in Angola since 2009. In 2010 she was also chosen as president of Benfica de Luanda, a team in Angola’s top football division. Furthermore, in 2008 she was elected to parliament at the age of 24, the youngest ever.

Luanda, Angola’s capital (Photo: Anton_Ivanov / Shutterstock.com)

Change of leadership

When dos Santos stepped down as president in 2017 after nearly 40 years, the position was handed over to João Lourenço. This handover was decided not by a public election but at an MPLA party congress. Lourenço had served as defense minister under the dos Santos administration. It was therefore thought that he was chosen with the expectation that he would carry on dos Santos’s will and continue the benefits enjoyed by the dos Santos family, and the transition initially appeared smooth.

Contrary to many expectations, however, Lourenço began a series of reforms soon after taking power that marked a clear break with dos Santos’s policies. These reforms included indicting dos Santos’s close allies and removing the dos Santos family from political positions and privileges. In his inauguration speech, President Lourenço pledged to the people to end corruption in Angola. As a first step, he granted those who had profited from corruption a six-month grace period to return funds to the national treasury in order to revive the economy. At the same time, his focus on removing the dos Santos family from decision-making positions has created tensions with the MPLA.

Inauguration of President João Lourenço (Photo: GovernmentZA / Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Isabel has been indicted by authorities on charges of corruption and money laundering, but she denies the allegations, asserting on Twitter that “I have acquired my wealth through my own character and intelligence, upbringing, professional ability, and perseverance.” She also claims the investigation is politically motivated. However, evidence has emerged linking the wealth she amassed to corruption during her father’s rule. In 2020, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed a vast trove of leaked documents, accounts, and emails about her business dealings known as the Luanda Leaks. The leaks showed that major foreign banks, accounting firms, and other companies in other countries were complicit in her corrupt practices. As a result of these allegations, her bank accounts in Angola and Portugal were frozen between 2019 and 2020. Thus, the woman once considered Africa’s richest has declined.

Dos Santos’s son, Zenú, who headed the state sovereign wealth fund, was sentenced to five years in prison in 2020 for sending US$500 million to Credit Suisse in London. Welwitschia was expelled from parliament in 2019. She claims persecution under the new administration and has moved abroad, but parliament ruled that her prolonged absence was unjustified.

Is it a fundamental reform?

The Lourenço administration has declared the eradication of corruption within the MPLA and the government a top priority. It has stated that it will not hesitate to bring down members of the former power elite if crimes are uncovered. President Lourenço said that after the six-month amnesty period for returning corrupt funds announced when he took office in 2017, only legal measures would be applied. He also symbolically signaled a transfer of power by removing the former president’s portrait from the 100-kwanza banknote.

At the same time, it is true that the current administration faces many obstacles in implementing reforms in Angola. Owing to years of conflict, subsequent reconstruction, and outflows due to corruption, Angola has accumulated enormous debts to foreign financial institutions. To revive the economy, President Lourenço followed the recommendations of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and moved to privatize more than 195 companies, including Sonangol.

Angola’s oil industry (Photo: Eni / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The biggest challenges within these reforms are the global decline in oil prices and high inflation. In an economy heavily dependent on oil, oil accounts for about 70% of export earnings and is the main source of U.S. dollars used for imports. Consequently, with falling oil prices, there is a shortage of foreign currency for imports. The impact has spread beyond major trading companies to the daily lives of ordinary citizens. The shortage of foreign currency has led to a devaluation of the domestic currency (the kwanza) since 2017, causing prices to soar and eroding people’s purchasing power. As a result, those whose economic activity relied on imports have suffered major blows.

There are also mounting challenges on the political front. Under the dos Santos administration, most of those who profited from embezzlement of state funds were members of the ruling MPLA. Under the new legal framework, those who may be required to return wealth accumulated under the previous regime are pushing back, and resentment toward the new administration is rising within the MPLA. As instability grows within the party, some factions have engaged in acts of obstruction against the Lourenço administration, and some claim that President Lourenço himself benefited from corruption under the dos Santos regime.

Major doubts have also arisen about the anti-corruption reforms. Are these reforms truly for the good of the country, or are they aimed at eliminating the influence of dos Santos and consolidating power in Lourenço’s hands? Suspicion has been fueled by the focus of anti-corruption measures on dos Santos and his inner circle. In addition, the president’s own chief of staff was indicted in 2020 for abusing his office for personal gain, yet he has not stepped down. According to Portugal’s public broadcaster TVI, he allegedly used a company he owns abroad to invest funds obtained from a Portuguese real-estate firm.

President João Lourenço (Photo: Paul Kagame / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In February 2021, President Lourenço himself was accused of corruption. According to a report by Pangea-risk, a consultancy specializing in Africa and the Middle East, Lourenço and his wife Ana Dias are being investigated by U.S. authorities for suspected violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). The allegations also include that companies linked to the president received government contracts, the presence of funds of unknown origin, and suspected violations of U.S. lobbying rules.

Conclusion

Angola has long faced great hardship through slavery, colonial rule, armed conflict, and the dictatorship of dos Santos and his family. Urgent reforms are needed to correct inequality and extreme poverty and to move the country forward.

While the reforms underway under the Lourenço administration may produce positive results for Angola, doubts have also arisen around them. By law, the former president is immune from prosecution for five years after leaving office, so he could be prosecuted starting in 2022. The new administration needs to broaden investigations beyond the dos Santos family while also dispelling suspicions directed at the president himself. At the same time, resistance within the party, falling oil prices, and the impact of COVID-19 are likely to hinder these efforts.

In the general elections scheduled for 2022, President Lourenço is almost certain to be one of the candidates. How will Angola change in the future? The outlook remains unclear.

※1 Providing benefits to supporters in return for political support

※2 A way of favoring relatives or those with the same local or family ties.

Writer: Délio Zandamela

Graphics: Minami Ono

Translation: Maika Kajigaya

0 Comments