On November 21, 2020, an incident occurred in which a lawmaker from the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD), who had narrowly defeated a candidate from the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD) by 54 votes in a constituency in northern Shan State in Myanmar’s general election, was killed. The SNLD has denied involvement in the incident, but the rift between the parties appears to have deepened. In Shan State, as well as in Kachin, Kayin, and Mon states, there were also constituencies where voting could not even be held due to serious security problems.

In recent years, global attention has focused on the conflict in Rakhine State in southwestern Myanmar and the Rohingya refugees fleeing from it, which pose a major threat to peace in the country. However, multiple long-running armed conflicts also persist in northern and eastern Myanmar. This article highlights the conflicts in Shan, Kachin, and Kayin states in northern and eastern Myanmar.

Myanmar government troops welcoming foreign guests (Photo: nznationalparty / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

The Birth of Burma

Myanmar is located in the northwestern part of the Indochina Peninsula, bordering Bangladesh, India, China, Laos, and Thailand, with its south and west facing the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Its population is about 56 million, around 60% of whom identify as Bamar (Burmese), with the remainder composed of numerous ethnic minorities. The sole official language is Burmese, though many minority languages and English are also used. The northern and eastern and western parts of the country are highlands, while the Ayeyarwady River runs north–south through the south; along the river lie major cities such as Yangon and the capital Naypyidaw, and a low-lying delta spreads out.

Looking back through history, various kingdoms and empires repeatedly expanded, merged, and split, resulting in borders that defined today’s territory inhabited by diverse peoples. A representative dynasty was the Pagan Kingdom, established in 1057 and built by the Bamar as the central power. The Pagan Kingdom lasted for about 200 years but collapsed in the late 13th century due to invasions by the Yuan army. Thereafter, the area around present-day Myanmar fragmented: the Shan dominated the north, while the Mon and Bamar controlled the south. Over time, the Bamar gained the upper hand in the south, and in the first half of the 16th century they again unified what is now southern Myanmar and established the Toungoo Dynasty. In the area where present-day Shan and Kachin states lie, the Ava Kingdom led by the Shan had been established, but it was destroyed by the Toungoo in the 16th century. The Shan then split into multiple groups centered on small chieftains, governing themselves autonomously, while maintaining tributary relations with the Toungoo. States in the region around present-day Myanmar continued cycles of fragmentation and unification, but pressure from Britain and the Netherlands intensified in the 19th century. After the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826) and the Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852), the territory of present-day Myanmar came under British control in 1885.

A temple from the Pagan Kingdom era in Myanmar. In Myanmar, most of the population practices Buddhism. (Photo: Piqsel [Public Domain])

At that time, Britain ruled the region including present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh as the British Indian Empire. Burma and surrounding areas that became British colonies were governed as the Burma Province of British India, with the capital in the southern city of Rangoon (now Yangon). Meanwhile, the northern and eastern frontier regions inhabited by Shan, Kachin, and Karen peoples were part of the Burma Province of British India but were designated as Frontier Areas and instructed to establish semi-autonomous administrations to govern their regions. As a result, certain degrees of autonomous self-rule continued from pre-colonial times. However, prior to colonization, these frontier areas were divided into multiple groups centered on small chieftains, so people with slightly different languages and cultures were mixed within the frontier regions. To make it easier to oversee these areas, Britain unilaterally classified about 135 ethnic groups.

Independence: From Burma to Myanmar

After Japanese occupation from 1942 to 1945 during World War II and subsequent British reoccupation, in 1948 the Burmese government drafted a new constitution and achieved independence as the Union of Burma. Most of the regions that had self-ruled as Frontier Areas, such as Shan and Kachin, agreed to join as states of the Union of Burma because full autonomy and equal distribution of national assets were promised at the 1947 Panglong Conference held in Panglong, a city in present-day Shan State. However, in 1962 the government was overthrown in a military coup, and a Revolutionary Council led by General Ne Win took power. Ne Win introduced the Burmese Way to Socialism, which placed Buddhism at its core and aimed to nationalize the economy, and abolished the federal system to impose direct rule. In response, armed groups emerged in northern and eastern states to resist.

In 1988, large-scale pro-democracy protests broke out in dissatisfaction with the socialist dictatorship. Although the protests were suppressed by the military, a subsequent coup by a younger group within the military established a new junta. Fearing resistance by anti-government armed groups, this regime further tightened its control over minority regions. Because the name “Burma” was that of the largest ethnic group in the Union, and to make domination of non-Bamar minorities even clearer, in 1989 the country’s name was changed from Burma to Myanmar. The name Myanmar is said to derive from the English pronunciation of “Burma” (mranma). In response to the 1988 popular protests, the 1990 Myanmar general election was held. The NLD led by Aung San Suu Kyi won more than 90% of the seats, but the government ignored the results and retained power, and a military regime continued for roughly the next two decades.

In 2011, with the inauguration of President Thein Sein, political and economic liberalization such as deregulation of foreign access to the Myanmar market, promotion of market liberalization, and press freedoms were implemented, bringing significant progress to Myanmar’s society and economy. On the other hand, the government has been reluctant to establish a federal system for fear of weakening national cohesion, and backlash has grown in minority regions that hope for a return to federalism. Here, we look in particular at Kachin, Shan, and Kayin states, where conflict has been especially intense.

Kachin State

Kachin State lies in northern Myanmar and borders China’s Yunnan Province. With a population of about 1.7 million, it is primarily inhabited by Kachin people. The state capital is Myitkyina; the northern part of the state is mountainous while the south is plains, and Kachin people mainly reside in the mountainous areas. It is estimated that 60% to 90% of Kachin are Christians.

Because Kachin State joined under the agreements made at the 1947 Panglong Conference, no armed groups were formed at the time of independence from Britain. However, as the central government gradually eroded its autonomy, the political organization opposing the government to expand autonomy, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), was founded in 1960, followed by its armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), in 1961. In 1962, when the Burmese government abolished the federal system and established Buddhism as the state religion, the KIO intensified its opposition. Although the KIO’s sources of funding are unclear, the government claimed the KIO financed itself through opium, an illegal drug. The government also carried out military interventions to seize natural resources in Kachin State—such as gold, jade, and tropical timber. Seeking a political settlement to Myanmar’s conflicts through federalism, the KIO continued ceasefire talks with the government, but fighting persisted. A ceasefire was finally achieved about 30 years after the KIO’s founding, in 1994. With the ceasefire, Kachin State’s natural resources came under the control of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), the military regime’s top decision-making body, while a certain degree of autonomy was granted.

After the KIO-Government ceasefire, hopes rose for a peaceful society, but in 2009 the Tatmadaw (government forces) requested that the KIO be transformed into a Border Guard Force (BGF). When the KIO refused, the Tatmadaw broke the ceasefire. This led to renewed fighting in June 2011, which intensified into 2012. Although de-escalation was agreed in May 2013, conflict has continued to the present day. Civilians have suffered as well, and roughly 100,000 people remain displaced, making it a large-scale crisis. The Kachin conflict exemplifies Myanmar’s typical center-versus-periphery dynamic between the KIO and the government forces.

Soldiers of the Kachin Independence Army (Photo: Allsyon Neville-Morgan / Flickr [CC BY NC-ND 2.0])

According to a study by Kachin civil society organizations for the “Permanent Peace Programme” in 2018, most internally displaced persons are farmers, and the return of land destroyed during the conflict with government forces is the most important issue. However, a negative spiral has emerged in which disputes break out over land restitution. Much of this land has been traditionally inherited or was purchased improperly, making it difficult to prove legal ownership with proper documents. In this context, since 2017 the government has pressured IDPs in camps to return to their original places of residence. However, clashes between armed groups have not ceased, and returns to areas without guarantees for shelter or food have sparked opposition.

Shan State

Shan State, the largest state in Myanmar, lies in the east and borders China’s Yunnan Province, Thailand, and Laos. Its population is about 5.8 million. The Shan, who primarily live there, are the largest minority in Myanmar and are estimated to number over 2 million; many other minority groups also reside in the state. The capital is Taunggyi, and the terrain is largely highland, including the Shan Hills and Shan Plateau. The dominant religion is Theravada Buddhism, as among the Bamar.

Like Kachin State, Shan State agreed at the Panglong Conference to exercise autonomy as a Burmese state. After independence from Britain, Shan State exercised autonomy, but in 1950 Kuomintang (KMT) forces defeated by the Chinese Communist government fled into Shan State’s mountains. Citing the need to secure Shan State’s safety, the Burmese government deployed troops to the state. While the army succeeded in repelling the KMT forces, it increased pressure on Shan State, and the state’s autonomy declined. From 1958 onward, several anti-government groups emerged to oppose this, including the Shan State Independence Army (SSIA). Fighting between anti-government forces and the army continued, and in 1964 existing resistance groups merged to form the Shan State Army (SSA), which fought to restore and expand Shan autonomy. Shan State faced another issue: drug trafficking. When the KMT fled into Shan State, they established drug-related bases in eastern Shan State along the Thai border, which led to active opium trade. Drug organizations later armed themselves and became parties to the conflict.

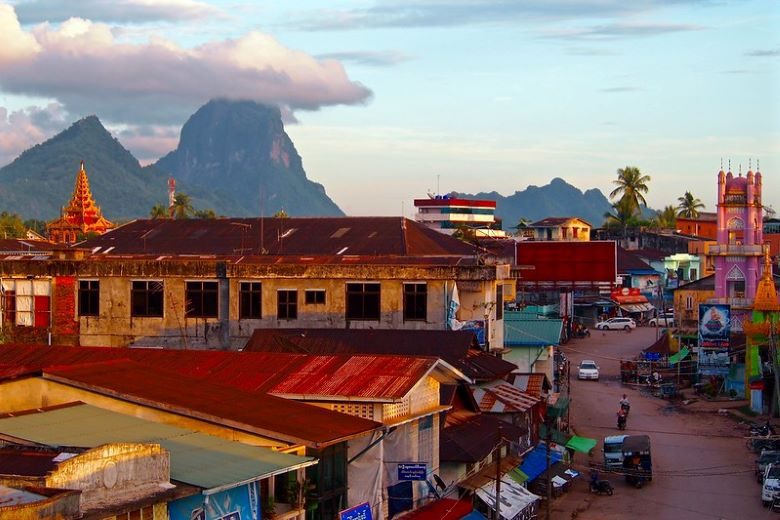

A settlement in the highlands of Shan State (Photo: Samuri Kangaslampi / Flickr [CC BY NC-ND 2.0])

In the late 1960s, new actors rose to prominence. China supported the moribund Communist Party of Burma (CPB), which advanced into northern Shan State, absorbed armed groups based in the state, and became a powerful anti-government force—financed by drug money intended to expand its military capacity. As a result, the Shan State Army was dissolved in 1976. In 1989, a mutiny within the CPB led to its fragmentation into groups such as the MNDAA (Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army) and the NDAA (National Democratic Alliance Army). The army subsequently reached ceasefire agreements in 1989 with anti-government organizations such as the MNDAA. From the 1990s for more than a decade, although there were clashes among groups, the period was relatively stable.

In April 2009, the military command announced that ceasefire groups would be converted into government Border Guard Forces, increasing pressure on anti-government forces. Thereafter, armed groups in northern Shan, such as the NDAA, decided to ally with organizations that had refused conversion orders in other states, including the KIO and the TNLA (Ta’ang National Liberation Army). The alliance of these groups with armed organizations in northern Shan came to be called the Northern Alliance, and fighting broke out with government forces and the Border Guard Forces. This conflict continues today, and thousands have fled both within the country and abroad.

Kayin State (formerly Karen State)

Kayin State is located in southeastern Myanmar and borders Thailand. Its population is about 1.6 million, and many ethnic groups, including Karen and Mon, live there. The state capital is Hpa-An, and the terrain is mountainous.

Cityscape of Hpa-An, the capital of Kayin State (Photo: Remko Tanis / Flickr [CC BY NC-ND 2.0])

Before Burma’s independence, Karen leaders were active as a political organization known as the KNA, but around the time of independence they developed into the anti-government armed group KNU (Karen National Union). The KNU refused to exercise autonomy as a Burmese state at the 1947 Panglong Conference. However, as the Burmese government sought to incorporate them as Karen State, conflict between the KNU and government forces began in 1949. Initially, the army advanced with support from armed groups across the country, but because Kayin State is mountainous and difficult to fight in, large-scale battles were rare even as conflict flared throughout the state. The situation changed dramatically in 1988, when the army moved to consolidate military rule by asserting control over Kayin State. In 1989, during this process, the junta changed the state’s name from Karen State to Kayin State. In 1994, attacks by the army caused the KNU to lose most of its controlled territory. As a result, multiple armed groups split from the KNU, such as the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA). These groups varied in nature, with some cooperating with the government and others continuing resistance.

In May 2013, a conference was held to promote political unity among five armed groups in Kayin, seeking to ease tensions among them. The KNU also reached a ceasefire with the government in 2012, and conditions have steadily improved. However, many displaced people remain in mountainous areas of the state, and there are still 100,000 refugees in neighboring Thailand, so problems persist. What they fear is the existence of numerous armed groups, and unless tensions among the groups and with the government are resolved, it will be difficult for displaced people to return to their former lives.

Myanmar’s Lower House of Parliament (Photo: Htoo Tay Zar / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Conclusion

Looking nationwide, one could say that the 2020 general election brought no major change, given the ruling party’s landslide victory. But what lies ahead for Myanmar’s many conflicts? Some observers note that in regions where conflict continues, there are not a few armed groups that have expanded their influence and military strength compared to the previous election and have affected the polls. In Kachin, Shan, Kayin, and other states, many citizens continue to demand basic human rights and autonomy, while various actors fight over resources and power, leaving the situation unstable. The Myanmar government may resort to force out of fear that granting autonomy will reduce its influence over minorities or trigger rebellion, but it remains necessary to continue dialogue to resolve conflicts so that citizens are treated equally and can live in safety.

Writer: Kaito Seo

Graphics: Yow Shuning

ミャンマーという比較的小さな国でも、いくつかの地域に分かれていたことから問題が起こっていることを理解しました。これから人々の意思がきちんと伝わった政治に変革していくことを願うばかりです。

ミャンマーのあまり報道されてない部分がよく解説されていてわかりやすかったです。

それぞれのグループの意思が尊重された形で問題が収束されていくといいなと思いました。

日本のメディアはあまり扱わない点を知ることができました。

少数派の資金調達源が麻薬やアヘンであることに驚きました。

仮にこの紛争が解決しても、その後にまた麻薬やアヘン取引の問題が浮上してくるでしょう。何をもって解決というか難しいなと思いました。