In October 2020, Chile held a national plebiscite on whether to draft a new constitution, and with 78% approval, the country decided to create a new one. The constitution to be abolished was created in 1980 under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. It minimized the state’s role in the economy and was designed to favor employers over workers. As a result, it has been one of the factors behind the social and economic inequalities that have long plagued Chile.

Today, Chile is one of the wealthiest countries in Latin America, yet also one of the most unequal in the world. Economic growth since the 1990s has reduced poverty and unemployment, but decades-long social and economic disparities persist. The top 1% owns 33% of the nation’s wealth, while many in the middle and working classes struggle to get by. Let’s take a closer look in this article.

Santiago, the capital (Photo: Sami Haidar/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

目次

History of Chile

In 1818, Chile gained independence from Spain, which had colonized the country. The late 19th century saw an industrial revolution and nationwide prosperity. Exports expanded and state revenues increased, but politicians, industrial capitalists, and landowners monopolized this wealth. As a result, by 1913 the top 1% owned 25% of national income. Meanwhile, in the latter half of the 19th century, oppression of the indigenous Mapuche by the Chilean government and military worsened. The rights of the Mapuche were ignored, their resource-rich lands were seized, and businesses were carried out on those lands. In this way, various forms of inequality took root in Chile.

Starting in 1938, administrations emerged that were conscious of this inequality and sought to reform the economic structure. In particular, between 1970 and 1973, President Salvador Allende advanced socialist reforms such as free healthcare. However, a coup in 1973 toppled Allende’s government and brought Pinochet to power. It is said that the CIA in the United States, then in the midst of the Cold War, was involved, fearing the spread of socialism in Latin America.

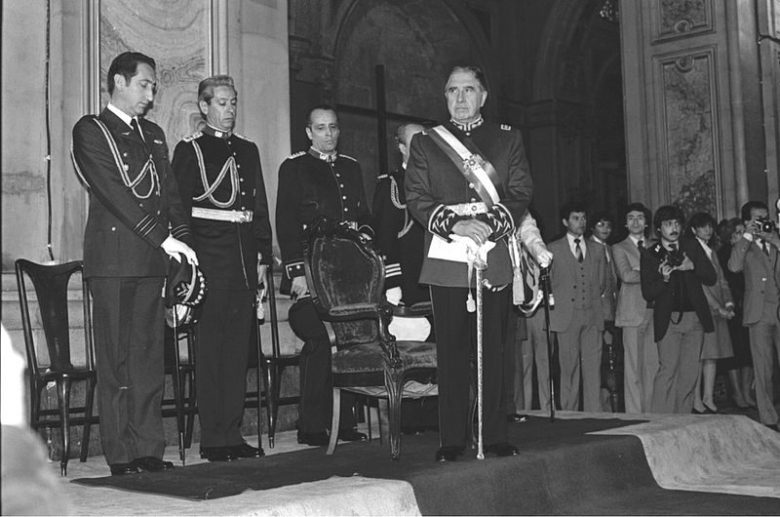

Former President Pinochet (Photo: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0CL])

Once in power, Pinochet established a dictatorship and implemented free-market reforms as part of his policies. These reforms were influenced by the “Chicago Boys”, a nickname for Chilean economists educated at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman, a neoliberal (※1) who developed monetarism (※2), in the 1950s. The Chicago Boys’ plan aimed for an economy with minimal government intervention and openness to imports, policies that were supported by the U.S. government. During the Pinochet dictatorship, the Chicago Boys joined the government, and some were appointed as ministers. Influenced by them, Pinochet’s policies minimized the role of the state, cut budgets for public housing, education, social security, and infrastructure, and privatized state-owned enterprises. Education, pensions, the healthcare system, and water resources came to be handled by private companies, and from 1973 to 1980 the number of state-run companies fell from 300 to 24.

In 1980, a new constitution was enacted. It reflected free-market reforms, restricting the government’s ability to expand social welfare or intervene in business, and favored corporate activities. The provision of social services shifted from the state to the private sector. Laws based on this constitution are also difficult to amend. Changing constitutional laws concerning matters such as education and elections requires 57% approval in both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, and such laws are readily subject to review by the Constitutional Court to determine whether they violate the constitution.

In 1990, a plebiscite was held and, with 56% approval, Chile transitioned to democracy and the dictatorship ended. However, even after the return to democracy, the laissez-faire economic system and the constitution from the Pinochet era were maintained, and the country pursued neoliberal policies such as free trade and export expansion.

[Created based on a map from Vemaps.com]

The “Economic Miracle” and Its Flip Side

Thanks to the laissez-faire economic system, Chile’s economy grew rapidly, and by 2018 its GDP had reached about nine times its 1990 level. This growth dramatically reduced poverty and unemployment. The poverty rate, which was 33% in 1992, fell to 8% by 2014. Real wages also rose steadily over 25 years. After this growth, Chile became one of the wealthiest countries in Latin America, and in 2019 its GDP per capita was the second highest in South America after Uruguay.

This growth was supported by the copper industry, substantial export revenues from international trade, and foreign investment. Copper looms large in Chile’s economy, accounting for 49% of exports. Mine workers earn high incomes and wages. The mining region of Antofagasta, home to the world’s largest open-pit copper mine, experienced the fastest economic growth and has the highest GDP per capita in the country. In addition to copper, Chile’s export ratio and rate of foreign investment are the highest in South America, underpinning its economic growth.

The Chuquicamata Mine in Antofagasta, the world’s largest open-pit copper mine (Photo: Tennen-gas/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

However, GDP only reflects the overall size of an economy and cannot measure how wealth is distributed or the degree of inequality. While economic growth reduced poverty and benefited the wealthy, inequality remained across society. Even though poverty has fallen, 50% of the population still lives on USD 500 or less per month. Inequality has worsened: in 2006 the income of the top 10% was about 30 times that of the bottom 10%, and by 2017 it had reached about 40 times. Land is also highly concentrated, with 1% of farms owning over 70% of the land. Chile is therefore counted among the 20 most unequal countries in the world. Furthermore, the copper industry that has supported Chile’s economy was hit when copper prices fell due to declining demand in 2014, affecting the broader economy.

Hardship in People’s Lives

Let’s look more closely at how people live in such an unequal country. The privatization of education, healthcare, the pension system, and water resources in the 1980s has perpetuated inequalities in social services between the wealthy and everyone else to this day.

A poor district in Santiago, the capital (Photo: C64-92/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

In education, the government spends only 0.5% of GDP on higher education, the lowest share among OECD countries. Of more than 150 universities, two-thirds are operated for profit by private companies. Average university costs account for about 41% of average income. As a result, children from wealthy families who can pay receive good educations. Families that cannot afford high educational costs are unable to equip their children with the skills education provides to obtain good jobs and high incomes, contributing to economic inequality. In 2007, government-backed student loans were introduced, enabling about 70% of students to pursue higher education. However, in exchange for access, many people struggle after graduation with massive loan repayments.

Healthcare and welfare also face problems. During the Pinochet dictatorship, a for-profit private healthcare system rose to prominence. Because private healthcare is far more expensive than the public system, many people use public healthcare. However, the public system is of lower quality than private care. Moreover, the world’s first privatized pension system fails to adequately protect the elderly in low-income brackets or those in non-regular employment. The average pension paid by private entities falls below the minimum wage of about USD 400. Under Chile’s retirement system, except for the military and police, there is no guarantee of retirement allowances from the state or companies after leaving work. Pensions are therefore crucial after retirement, but amid rising prices they are not enough to live on. In 2008, then-President Michelle Bachelet reformed pensions for the poorest retirees, yet even so, many still cannot secure enough income for their later years.

Former President Bachelet enacts a law to provide pensions (Photo: Gobierno de Chile/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Further, due to labor rights defined by the Pinochet constitution, society has been shaped in favor of employers. Workers’ rights to negotiate with employers have been hollowed out. In particular, non-regular workers lack sufficient protections such as severance pay, employer-paid insurance for workplace injuries, and union rights, leaving them working for low wages. Even regular workers have their right to organize restricted by labor regulations dating back to the Pinochet era.

The tax system is also inequitable. It imposes heavy tax burdens on the poor, reducing the money people can actually spend on daily life even when wages are rising in nominal terms. As a result, many cannot buy sufficient food and necessities, and not a few among the poor suffer from malnutrition. Meanwhile, many wealthy and powerful individuals are said to repeatedly engage in tax evasion and corruption.

Chile’s water resources are completely privatized, and even water flowing through one’s own property cannot be drunk or used at will. In addition, the beverage, fuel, firewood, and energy industries are owned by three large companies and distributed to the public. These three companies set prices and monopolize essential services.

Outbreak of Mass Protests

As these inequalities were not remedied, people began to push back against social and economic disparities. In 2011, students led protests against inequities in the education system, and in 2016 there were demonstrations against the pension system. In response, then-President Bachelet implemented reforms in human rights, healthcare, pensions, taxation, and education, but they did not sufficiently resolve the issues.

Even after these protests, social and economic inequalities failed to improve, and in October 2019, a hike of about USD 0.04 (30 pesos) in subway fares triggered massive demonstrations centered in Santiago that spread nationwide. About 1.2 million people joined in a single day; 22 people died, more than 2,200 were injured, and over 6,000 were arrested—marking the first deployment of the military since the return to democracy. The protests were so large and sustained that Chile canceled two international events it had been set to host: the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in November 2019 and the 25th UN climate conference (COP25) the following month.

Protests that erupted in 2019. The person in front is holding a Mapuche flag. (Photo: cameramemories/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

“It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years.” This became the slogan of the 2019 protests, indicating that the demonstrations were not about a 30-peso fare hike, but about three decades of economic inequality since the return to democracy. The 2019 protests were rooted in long-standing hardships in daily life and social and economic disparities in Chile.

President Sebastián Piñera, in his second term (※3) in 2018, initially took a hardline stance against the protests. As they grew and he could no longer contain them, he announced increases in government pensions, a higher minimum wage, lower medical costs for the elderly, higher taxes on the wealthy, and pay cuts for politicians. However, the government moved slowly, and the protests did not subside.

In 2020, pandemic lockdowns dealt a heavy blow to the economy, and demonstrations by those facing hardship continued. As a concession to quell the protests that had persisted since 2019, the government held a plebiscite on drafting a new constitution.

The Road to a New Constitution

As noted at the outset, a plebiscite in October 2020 decided that the constitution would be rewritten. The convention of 155 representatives to deliberate and draft the new constitution was scheduled to be elected in 2021. It is hoped that the new constitution will help resolve the inequalities that have long troubled Chile. In addition, relations between the state and indigenous peoples have deteriorated. There have been violent acts by indigenous groups opposing companies advancing onto indigenous lands. Because the current constitution lacks provisions on indigenous rights, it is hoped that the new constitution will recognize indigenous rights and secure political rights.

A session in Chile’s Congress (Photo: Diputadas y Diputados de Chile/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In recent years, income inequality and poverty have narrowed across Latin America as a whole, yet the distribution of wealth remains the most unequal in the world. In many countries in the region, economic growth has been limited, and poverty and inequality are more severe than in Chile. Even so, as we have seen, Chile has experienced economic growth and reduced poverty since 1990, while social and economic disparities persist. It is hoped that the new constitution will enable Chile to fundamentally remedy the decades-long inequalities centered on education, healthcare, and pensions.

※1 Neoliberal: A position that deregulates, minimizes government intervention in markets, and leaves the economy to the results of free competition.

※2 Monetarism: Proposed by Friedman, the idea that aside from controlling the money supply, the government should refrain from intervening in markets.

※3 Piñera served as president from 2010 to 2014 and again from 2018. Between 2014 and 2018, Bachelet was president.

Writer: Saki Takeuchi

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

この記事を読んで、近年チリで起きていたデモの背景をより深く理解できました。新憲法作成によって格差が改善されていくことを期待します!

チリが、中南米で最も裕福な国である一方で、世界で最も不平等な国ということに驚いた。憲法が全ての悪循環を生み出していると思うので、この憲法改正を機に少しでも改善されることを願う。