In September 2020, Kenya’s Chief Justice pointed out that the proportion of women in Parliament falls below the one-third threshold stipulated by the constitution and advised the president to dissolve Parliament. Women make up 21% of the Senate and 31% of the National Assembly in Kenya, placing the country slightly above the global median at 91st in the world index of women in politics. Even so, this is far from an equal split between men and women.

Gender equality is an issue that affects every area of our lives and has long been a social challenge. At the Fourth World Conference on Women held in 1995, the Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action were adopted to advance women’s empowerment. The Beijing Declaration was significant as a guiding framework for subsequent efforts to promote gender equality, incorporating perspectives of minority women into women’s empowerment. However, 25 years after the Beijing Declaration, senior officials at UN Women (UNW) warn that “not a single country has achieved gender equality.”

Here, we focus on gender inequality, examine the current situation and the factors that make progress difficult, and also look at examples from countries that are advancing gender equality.

25 years since the Beijing Declaration: Scenes from the Beijing+25 meetings (Photo: UN Women/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

What is gender equality?

Before looking closely at gender equality, let’s clarify what “gender” means. In contrast to biological sex (male/female), “gender” refers to socially, culturally, and historically constructed differences between men and women. Related terms include the following:

Gender identity: “How one recognizes one’s own gender; it does not necessarily align with one’s biological sex; gender identity.”

Gender bias: “Sex-based prejudice; mindsets and behavioral patterns constrained by socially conventional views of men and women.”

Gender role: “Gender-based division of roles; behaving in ways that match society’s gendered images.”

People whose biological sex and gender identity align are sometimes referred to as cisgender, while those whose do not are referred to as transgender.

Why is gender equality important? Gender equality refers to a society in which men and women have the same opportunities, rights, and responsibilities—in other words, a society where everyone can live with equal human rights. In reality, however, rights deprivation and denial, discrimination and unequal opportunities, and violence based on gender occur around the world. Gender inequality has repeatedly been raised as a concern at international fora, and the importance of efforts to eradicate it has been emphasized time and again. Reflecting this global momentum, the 1995 Beijing Declaration included important perspectives such as “ensuring the full realization of the human rights of women and girls as an inalienable, integral, and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental freedoms” and “intensifying efforts to ensure the equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all women and girls who face diverse obstacles to their empowerment and advancement due to factors such as race, age, language, ethnicity, culture, religion, disability, or because they are indigenous.” Yet despite such efforts and repeated discussions at international conferences, as noted above, the situation remains that “not a single country has achieved gender equality.” What forms do gender-based inequalities, violence, and rights deprivation take in practice?

The current state of gender inequality

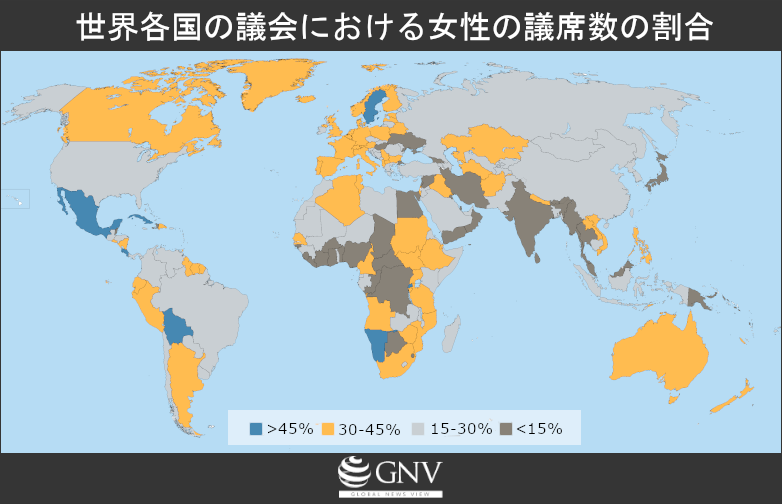

Let’s look at the current state of gender inequality from several angles. In politics, many countries still have extremely few women representatives in lawmaking and decision-making bodies. Men account for 75% of politicians worldwide, well over a majority. According to 2019 data covering 193 countries, women hold a majority of seats in national parliaments in only three countries—Rwanda, Cuba, and Bolivia—and only 15 countries have parliaments in which women hold 40% or more of the seats (Note 1).

Created based on UN Women data (2019)

What problems arise when women are absent or underrepresented in policy-making and national decision-making? Due to differences in embodied experiences between men and women—such as pregnancy, childbirth, and fear of sexual victimization—the way social issues are perceived can differ in many contexts. When women legislators are extremely few, these issues are less likely to reach the agenda, and systems and laws to correct gender inequality are less likely to be created. As a result, these problems persist in society. Moreover, in representative democracies, politicians serve as the representatives of citizens. If the gender balance among politicians—the representatives of citizens with diverse views, ideologies, and concerns—is skewed, the voices of diverse citizens are less likely to be reflected in policy, potentially undermining democratic legitimacy. In addition, increasing the number of women legislators has been shown to bring various broader benefits. For example, a study in Canada found that more women in government promoted health and welfare and was associated with a decrease in overall mortality rates.

Gender equality is also lagging in the economic sphere. For example, 73% of positions involved in corporate management globally are held by men, and gender discrimination exists in workplaces and employment. With many men occupying executive roles, it is not uncommon for organizational practices—such as employment conditions—that disadvantage women to persist. Moreover, gender wage gaps and employment gaps are also significant issues.

Everyday life and the household are not free from gender inequality either. Comparing the time spent on domestic labor and unpaid care work, women spend on average three times as much time on such work as men. This stems from the historical expectation—based on gender roles—that women undertake domestic labor and unpaid care work, an expectation that persists today. Longer hours of domestic work also make it more likely that women, even if they want to work in paid jobs, cannot do so—creating a vicious cycle. In addition, it is known that one in three women worldwide experiences violence, including sexual violence, from a partner or family member at some point in their lives.

Chile: Demonstration by women calling for the repeal of the abortion ban (Photo: Fran[zi]s[ko]Vicencio/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Other issues include differences in school enrollment rates between girls and boys across countries, whether women have autonomy over sexual and reproductive health, and laws and social customs that restrict women’s marriage or dress.

Not everyone with the same gender has the same experiences. Multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination and oppression can combine to create complex and specific structures of disadvantage. Looking at gender inequality, the experiences of women vary based on factors such as skin color, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic class. For instance, during the abolitionist and women’s liberation movements in the United States, the experiences of “Black women” were marginalized, often being dismissed or erased. Intersectional discrimination still occurs in many contexts today, and understanding the complex, overlapping structures of oppression within the context of gender inequality is an essential perspective for achieving gender equality.

The issues discussed so far present significant human rights concerns by placing heavy burdens on women’s self-actualization and ability to live authentically in society. In addition, gender inequality is closely linked to life-and-death issues, exacerbating poverty and hunger, and exposing women to greater impacts from conflict than men.

G20 summit reported as a gathering of “world leaders”: Even among these “world leaders,” gender imbalance is conspicuous (Photo: OECD/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Factors impeding the realization of gender equality

As noted, gender equality is far from realized today, with problems piling up. What underlies the persistent failure to achieve gender equality?

How did the social structure of male dominance and female subordination come about? As far back as the era of hunting and gathering, labor was divided by sex. While the forms of division differed by region and community, in most cases men took on roles related to hunting, war, and politics roles. This suggests that from quite early in human history men held political power, and that women’s positions were subsequently subordinated in society. Research also shows that in all societies studied, women’s sexual behavior has been controlled by men and older women. Over a long period, labor division by gender placed women in an inferior social position; with the advent of capitalism, however, the valuation of labor changed. In capitalist economies, labor is recognized by the profit it generates, which reduces, to some extent, the importance of the worker’s gender diminished. As a result, the importance of gendered divisions of labor waned, and men and women increasingly stood on the same playing field as workers. This underpinned movements to redress gender inequality and the emergence of the slogan “equal pay for equal work.”

On the other hand, because capitalist economies prioritize profit generated by labor, work that does not produce monetary gain is not properly valued socially. This helps explain why the social value of domestic labor and unpaid care work—tasks that, based on historical gender roles, are still performed largely by women—has not been adequately recognized, contributing to women’s socio-economic subordination. During World War I and World War II, labor shortages among men in many countries led to women’s employment and wages rising. However, after the wars ended, women were often dismissed or saw their wages reduced, and women’s employment conditions in many cases reverted to pre-war levels.

Women engaged in the production of practice bombs. Australia (1943) (Photo: State Library of South Australia/Wikimedia [CC BY 2.0])

One reason gender equality remains unrealized today is the persistent problem of prejudice and stereotypes based on gender issues. In societies steeped in gender bias and stereotypes, women politicians and business leaders are less likely to emerge, and the resulting vicious cycle makes policies for gender equality harder to implement. In some cases, men—who often hold advantages in many areas today—perceive the realization of gender equality as a threat to their privileges and rights. Religion also influences gender inequality in various ways. In many cases, religions are male-dominant in their beliefs, imagery, language, and practices. A study of the world’s major religions (Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism) found that societies with stronger religious influence are more prone to gender inequality than those with weaker influence.

Moreover, social customs that reinforce or sustain gender inequality also contribute to its persistence.

Countries advancing gender equality

Globally, gender equality remains far from achieved. However, at the country level, some nations are enacting systems and policies and undergoing social transformations to realize gender equality. The example from Kenya at the beginning can also be seen as one such step. One index that quantifies countries’ efforts toward gender equality is the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report. Updated annually since 2006, it ranks countries based on gender gaps in four areas: politics, economy, education, and health. The top 10 countries in the 2020 Global Gender Gap Report are shown in the figure below.

Here, from among these 10 countries, we highlight Iceland, Nicaragua, and Rwanda, which differ in region, history, and development status.

Iceland

Iceland has ranked first in gender equality 11 times. In the Global Gender Gap Report, a score of 1 indicates full parity and 0 indicates complete inequality. Iceland’s total score was 0.877. What underlies its high level of gender equality? Historically, while men were away at sea for long periods fishing, women played various social roles; moreover, Icelandic mythology includes both male and female deities, recognizing the importance of both. Consequently, women traditionally held high status religiously, politically, and socially. However, with the spread of Christianity, it became less acceptable for women to symbolize “the divine,” and over time women’s social status declined.

In response, movements led by the Icelandic Women’s Association won partial suffrage for women in 1915 and full suffrage equal to men in 1917. With rising female enrollment in higher education, feminism in Iceland became more active around the 1960s–1970s, and in 1975 a large-scale strike demonstrated the economic importance of women’s labor. In 1976, legal equality between men and women was guaranteed, and in 1980 the modern world’s first woman was elected president—marking important historical steps. With measures such as corporate gender quotas (Note 2), women now hold over 44% of corporate board seats.

Even in the world’s closest country to gender parity, challenges remain. According to 2018 data, one in four women in Iceland has been a victim of sexual crime, and only 12% of victims report the crime. The reasons include victim-blaming and insults directed at survivors, as well as distrust of the judicial system.

Demonstration in Iceland calling for the eradication of gender-based violence (Photo: Tom Burke/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Nicaragua

Nicaragua ranks in the top 10 of the Global Gender Gap Report in the Americas, ahead of high-income countries like Canada and the United States. Though often described as one of the world’s poorest countries and not comparable economically to the Nordic top performers, Nicaragua’s progress on gender equality reflects various government-led policies. For example, through the “Budget Planning Program for Women’s Participation and Gender Equality,” budget planning and policies integrating a gender perspective have been promoted. Recognizing gender equality as a key component of democracy, the government has ensured that gender perspectives are considered at all levels of society—policy-making, redistribution of public resources, leadership positions, and work typically performed by women.

There is also a “Child-Friendly and Healthy Schools Initiative,” under which schools have undertaken thorough efforts to eliminate gender inequality. By applying equal treatment of girls and boys across all tasks in school life, Nicaraguan children learn early on that men and women are equals.

While in Nicaragua the proportion of women in secondary and higher education exceeds that of men, university attendance overall is low compared to global figures, and attending university itself can be difficult for many, reflecting domestic and international inequalities. Although abortion is banned in Nicaragua, the Global Gender Gap Report does not include abortion-related laws and systems in its index, leading some to argue that the index alone cannot accurately capture the country’s gender equality situation.

Early childhood education in Nicaragua (Photo: Global Partnership for Education/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Rwanda

Rwanda ranked 9th in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report. Focusing on the political subindex, it ranked 4th, reflecting particularly strong advances in the political sphere. The only Sub-Saharan African country in the top rankings, Rwanda’s progress is closely tied to the history of the 1994 genocide. Prior to the genocide, as in many countries, women in Rwanda were primarily responsible for domestic labor and childcare, and it was rare for them to hold high economic power or social status.

In the approximately 100 days of the 1994 genocide, an estimated 800,000 people were killed. With women comprising 60%–70% of the population afterward, a situation arose in which women had to take on jobs previously done by men. Recognizing that women’s participation was essential to national reconstruction, the government invested in women’s education, introduced parliamentary gender quotas, and promoted the appointment of women to civil service positions. As a result, women now hold over 60% of parliamentary seats—the highest share in the world—contributing to broader gains in women’s rights and status nationwide. For example, the national carrier RwandAir and major financial institution Bank of Kigali have appointed women as CEOs.

At the same time, heavy domestic burdens on women and the fact that one in five women experiences sexual violence (often by a husband) remain entrenched challenges tied to gender inequality and social norms that persist. Rwanda’s cross-party women parliamentarians played a major role from drafting to passage of anti-violence legislation, and future developments in addressing these issues bear watching.

Rwanda’s parliament (Photo: Paul Kagame/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Thus far we have viewed gender inequality primarily through the lens of men and women, but gender equality cannot be neatly reduced to this binary. Gender equality that includes the diverse “genders” of people who cannot be neatly categorized into male or female is essential to building a world in which everyone can live peacefully, safely, and securely. We must reexamine the current problems and take concrete, effective policy and action now to realize gender equality.

Note 1: All figures for bicameral parliaments use the lower house. The 15 countries with the largest shares of women MPs, in descending order, are: Rwanda 61.3%, Cuba 53.2%, Bolivia 53.1%, Mexico 48.2%, Sweden 47.3%, Grenada 46.7%, Namibia 46.2%, Costa Rica 45.6%, Nicaragua 44.6%, South Africa 42.7%, Senegal 41.5%, Finland 41.5%, Spain 41.1%, Norway 40.8%, New Zealand 40.0%.

Note 2: The quota system is a system of allocation by which, during hiring or in the selection of legislators, a set ratio is established to prevent imbalances based on gender, race, etc.

Writer: Azusa Iwane

Graphics: Yow Shuning, Minami Ono

非常に読み応えのある記事でした。女性の議員やトップを増やしていくにはやはりクォータ制が1つのカギであること、子供の頃からの教育が大事であることがよくわかった。

ジェンダー平等を推進できている国としてよく北欧が挙げられていますが、この記事ではニカラグアやルワンダなどの事例についても知ることができ、とても興味深かったです。

大変興味深い記事でした。

これまで、クォーター制度を取るのは逆に意図的に女性を特別扱いすることになるのでは、等と思っていました。しかしながら、女性議員が少ないことで多様な市民の声が反映されないというデメリットに気づかされました。

こういった状況を改善するためにどういった行動が必要なのでしょうか。

具体的に何をすればジェンダー不平等が改善されるのかが見えていない限りは早い改善は見込めないだろうと思います。

ニカラグアとルワンダのように、日本もジェンダー平等を推進させるべきです。今まで、女性議員の数が少なすぎるため、女性のための政策を通すことができないかと思いました。

ジェンダー格差なかなか減らないなか、ジェンダー平等に取り組んでいる国が少なからずあることに驚いたとともに、この動きがもっともっと広がればいいなと思いました。特に、ニカラグアでは学校生活の中で男女の平等な扱いを実施することによって、男女平等を早い段階から感覚的に学ばせるというのは良い取り組みだなと思いました。