US$1.3 trillion. This is the total amount of profit that companies worldwide are shifting to tax havens. The figure was estimated by the UK-based NGO tackling tax haven issues, the Tax Justice Network (Tax Justice Network). Corporate tax is levied on company profits, but profits are shifted from the countries where economic activity actually takes place and profits are earned to tax havens with little real economic activity, making it appear as if the profits were earned there. In this way, corporations avoid paying the corporate taxes that would otherwise be due. Following these shifted profits further, it is estimated that they cause US$330 billion in tax losses globally.

These estimates are based on the newly released data on multinational enterprises published for the first time by the OECD in July 2020. Although the data is only partial on a global scale, the amounts are striking. Of particular note is that among the top five territories causing the largest tax losses due to profit shifting to tax havens are three small islands around the Caribbean: the British Overseas Territory of Bermuda, the U.S. unincorporated territory of Puerto Rico, and the British Overseas Territory of the Cayman Islands. While tax haven issues exist in many places, the Caribbean islands have relatively small populations and economies compared to other jurisdictions ranked near the top. Why, then, have they become such massive tax havens? Four years had passed by 2020 since the release of the Panama Papers that brought tax havens to global attention. Has there still been no improvement in the Caribbean or globally? This article focuses on the Caribbean tax havens that connect the world economy.

Scene from the OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (Photo: OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development / Flickr [CC BY-NC2.0])

目次

What is a tax haven?

First, let’s explain what a tax haven is. According to Kojien (Iwanami Shoten, Kojien 6th edition), a tax haven is “a country or region that imposes no taxes or extremely low tax rates on foreign companies.” In other words, by basing economic activity in a tax haven, companies and wealthy individuals can reduce their tax bills.

Another major characteristic of tax havens is secrecy. Typically, jurisdictions considered tax havens restrict the disclosure of information about companies established there and their owners. By marketing the ability to move and park funds without being traced, tax havens attract the assets of corporations and the wealthy. For this reason, tax haven jurisdictions can also be called secrecy jurisdictions. A tax haven can be an entire country, or a territory or state. Because tax rates and levels of secrecy vary by jurisdiction, tax havens are actually difficult to define precisely.

Why, then, do countries or territories choose to become tax havens? A major reason is that by imposing no or low taxes on foreign companies, they can attract a large number of company incorporations and profit shifting. The more corporate activity and transactions that flow through, the more fees are generated, and even small margins add up and fuel the local economy. In addition, attracting large foreign banks, law firms, accounting firms, and consultancies can stimulate economic activity.

Protest against tax havens: a parody of tycoons indulging themselves with money extracted from low-income countries (Photo: Enough Food IF / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

A hallmark of tax havens is the presence of shell companies. A shell company is a company that is legally registered as a corporation but has no substantive business activities. Companies can set up shell subsidiaries in tax haven jurisdictions and shift profits to them, thereby reducing corporate taxes and other levies. Tax havens are not used only for intra-group profit shifting, however. They are also used to avoid taxes on transactions with other companies, to store or hide funds through trust accounts, and to disguise the origins of funds for money laundering and other purposes.

Is the use of tax havens legal or illegal? In fact, it depends on how they are used. Using the law and its loopholes for tax avoidance is legal. By contrast, hiding behind secrecy to break the law and engage in tax evasion, illicit financial flows, or money laundering is illegal. Moreover, there is no shortage of uses that fall into a grey area where it is difficult to judge legality.

Use of tax havens is not a rare exception at the margins of the global economy. They have become very common, routinely used by large corporations and major financial institutions. As a result, the scale of tax havens in the world economy is staggering. It is said that more than half of global trade passes through tax havens. One startling statistic suggests that assets held in tax havens amount to up to about one-third of world GDP, or roughly US$32 trillion. It is also said that 40% (US$15 trillion) of global foreign direct investment (FDI) is “phantom,” used merely for profit shifting through shell companies in tax havens. Furthermore, an amount of money ten times the aid flowing into ODA-eligible countries is said to exit through the back door via tax havens due to illicit financial flows, and the like.

View of Hamilton, the capital of the British territory of Bermuda, from a ship (Photo: TravelingOtter / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Tax havens from the perspective of corporations and the wealthy

Let’s shift perspectives and see how companies and wealthy individuals use offshore entities and other tax haven mechanisms. With so much possible online, it is now easy to set up a shell company both at the corporate and individual level. First, through an online agent, one selects the tax haven jurisdiction and the purpose of the entity. Next, one decides on the number of nominal directors, employees, and shareholders, and the banks to use. After paying the fees, the shell company can be established in a few days. To increase secrecy from there, complex networks are created by routing through multiple tax havens and multiple shell companies. At the individual level, when making large purchases such as private jets or yachts, one can establish a shell company in a tax haven and lease the asset from one’s own company to avoid taxes.

For multinational enterprises, systems for intra-group profit shifting via tax havens become institutionalized. The diagram below shows the tax payments and profit generation of a multinational using tax havens, before and after profit shifting. If a company pays taxes in a high-income country (Country A) where its headquarters are located in line with where real economic activity occurs, without shifting profits to an affiliate in a tax haven (Country/Territory B), it pays normal taxes under that country’s laws in proportion to profits. However, by shifting profits to Country/Territory B, the affiliate’s book profits appear higher and tax payments can be reduced.

There are various routes for profit shifting, but mainly three patterns. First is debt shifting: the headquarters assumes intra-group debt from an affiliate in a tax haven. Profits are shifted under the guise of paying interest to the affiliate, thereby lowering tax payments. Second is shifting intellectual property: a company places its IP in a tax haven affiliate and has group companies pay royalties to that affiliate. This makes it appear that profits are earned by the affiliate, reducing taxes. Third is transfer pricing: for example, when exporting a product, the tax haven affiliate first sells at a low price to a group company. By routing through the affiliate, the exporter’s profits in the home country are depressed, and the affiliate then resells at a higher price to the actual customer. In this way, it appears that the product’s profit was earned in the tax haven, avoiding taxes.

A vast financial infrastructure has developed to support these complex structures and transactions in tax havens. For example, law firms, attorneys, banks, accounting firms, and even governments cooperate with and support profit shifting and tax avoidance.

Concrete examples of such complex networks include LuxLeaks and the major corruption case in Malaysia. The former revealed how the Big Four accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) colluded with Luxembourg’s tax authorities to grant favorable tax rulings to more than 340 clients. The latter involved former Prime Minister Najib Razak diverting US$4.5 billion from the state investment fund 1MDB, embezzling nearly US$700 million of it. In the process, major financial institutions in the United States and Germany provided loans to shell companies in multiple tax havens. With powerful actors involved and intricate networks constructed, the flow of funds can be kept out of public view.

The current state of tax havens around the Caribbean

Which region hosts the largest tax havens in the world? According to the OECD data released for the first time in 2020, the jurisdiction causing by far the greatest tax losses through profit shifting was the Netherlands. Note, however, that the data covers only 26 countries and does not include major economies such as the United States. Furthermore, it is said that about half of the world’s phantom FDI is accounted for by Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

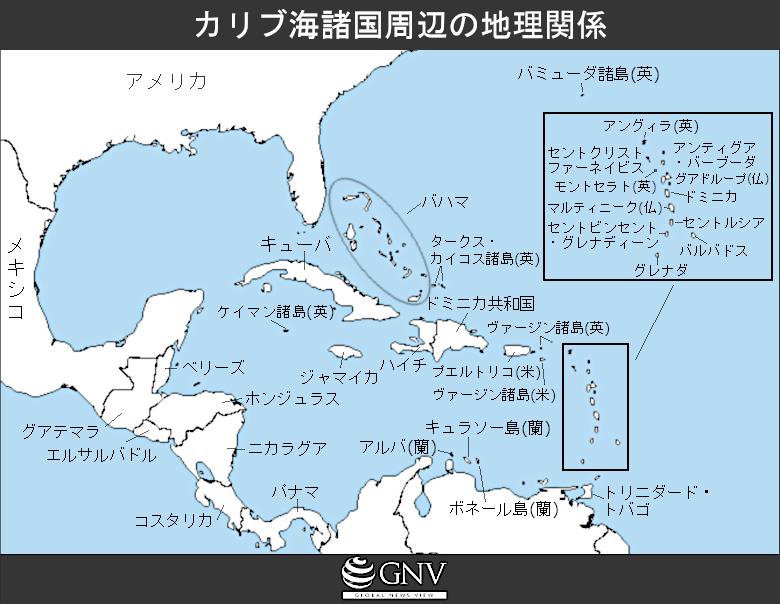

However, taken together, all the countries and territories in and around the Caribbean (※1) constitute the world’s second-largest tax haven region. Looking in detail at multiple rankings published by the Tax Justice Network, such as the Corporate Tax Haven Ranking (which indicates jurisdictions’ contribution to corporate tax avoidance) and the Financial Secrecy Ranking (which indicates secrecy), several islands around the Caribbean stand out near the top. In the corporate tax avoidance ranking, the British Virgin Islands ranks 1st, Bermuda 2nd, and the Cayman Islands 3rd. In the secrecy ranking, the Cayman Islands ranks 1st and the British Virgin Islands 9th. Most of the Caribbean consists not of independent states but of territories belonging to the UK, the US, the Netherlands, and others.

Considering the populations and sizes of the Caribbean islands, the tax haven problem is serious. For example, the Cayman Islands has a population of 60,000 but more than 110,000 registered companies. In addition, there are past reports that the share of assets and liabilities held by banks in the territory ranks the Cayman Islands 4th in the world, ahead of Germany and Japan. Moreover, excluding long-term Treasury securities, the Cayman Islands is the world’s largest holder of U.S. securities, and about 60% of the world’s hedge funds are domiciled there. The UK’s Bermuda (population 63,000), the British Virgin Islands (population 29,000), and the Cayman Islands (population 64,000) all have inward FDI stocks that exceed those of major countries such as Japan, Canada, and Italy.

These Caribbean islands are thought to serve as hubs connecting Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and others. For example, foreign claims of financial institutions in the Cayman Islands are dominated by U.S. and Japanese institutions, each accounting for about 30% of the total. Many of the world’s largest banks have multiple bases in the Caribbean. For example, Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking’s investor services for overseas asset administration operate through a company in Bermuda. The Bank of China has a major base in the British Virgin Islands. The U.S. bank JPMorgan Chase has a base in the Cayman Islands. In this way, many companies and financial institutions from major countries maintain presences in Caribbean tax havens.

Sunset at a resort in the Cayman Islands (Photo: slack12 / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

History and background of tax havens in the Caribbean

Tax havens exist around the world and have a long history, but why are so many found in the Caribbean? One early catalyst was that in the 1930s, American criminal organizations and their attorneys focused on the Caribbean as a base for money laundering—turning illegal funds into legal ones abroad and bringing them back. At first they used casinos in Cuba for money laundering, but after the Cuban Revolution shuttered the casinos, operations reportedly shifted to the Bahamas and Bermuda.

After World War II, the British Empire moved toward its end and relinquished its colonies. Companies operating in these areas began to exploit various legal loopholes to protect their profits. It is said that the British government not only failed to stop this but in some respects even cooperated. The Bank of England, the UK’s central bank, set one of the key precedents in 1957: a rule was adopted that even within British territories, transactions conducted in currencies other than sterling by users who were not UK residents or companies would not be counted as UK transactions. Laws in places like the Cayman Islands were then aligned with this, and the system rapidly spread across the UK’s Caribbean territories, the City of London, Jersey, the Isle of Man, and more. While the UK’s Caribbean territories were granted some degree of self-governance, they remained British territories. In setting up and maintaining tax haven mechanisms there, the UK is said to have exercised control while making it appear as if it was not. Because the network stretched from London to the UK’s Caribbean territories, Britain’s tax haven network was dubbed its “second empire.”

When the Bahamas gained independence from the UK in 1973, much of the money in its tax haven system moved to the Cayman Islands. Although the Bahamas’ system did not change substantially with independence, many wealthy individuals and companies reportedly felt more secure in the Cayman Islands, which remained under British control Cayman Islands. From there, the primary role of tax havens gradually shifted—from handling mafia money to serving general trade, hedge funds, insurers, and others seeking to avoid taxes.

Beyond the UK, the United States has long leveraged the quasi-colonial status of Puerto Rico to incorporate tax haven features. The Netherlands, another major global tax haven jurisdiction, also long viewed its territories where it manages defense and foreign affairs—such as Curaçao and Aruba—as lucrative assets. When these islands obtained fiscal autonomy, their governments sought to develop them into financial centers with favorable tax laws, supported by the Netherlands.

Recent progress

In recent years, the OECD and G20 have finally begun to move to address the tax haven problem. The Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) for automatically sharing financial account information multilaterally is making gradual progress, and by 2019, 100 countries were participating. Authorities can now account for funds in 84 million accounts totaling US$11 trillion. By requiring the reporting and publication of data through the OECD, even a partial improvement in transparency could help detect and deter widespread tax abuse.

However, AEOI faces problems: major powers such as the United States are not participating, and participation is also an issue for low-income countries that suffer the most harm from tax haven activity. Low-income countries often lack the equipment and resources to collect banking information, making it difficult for them to participate. Because AEOI is based on reciprocity, low-income countries face limits in providing account data from within their own borders and therefore cannot receive sufficient data from other countries.

In other developments, triggered by the UK’s exit from the European Union (BREXIT), in February 2020 the EU added the Cayman Islands to its blacklist of countries and territories that fail to crack down on aggressive tax avoidance. This is considered major progress—the first time a UK tax haven has been placed on the blacklist. However, major tax havens like Bermuda, the Bahamas, and the British Virgin Islands were not added. Nor did the EU impose restrictions on tax havens within the EU, such as the Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Cyprus.

Thus, while there has been some progress in countermeasures against tax havens, the scale of the problem is enormous and now deeply embedded in the global economy, making it hard to resolve. Comprehensive measures have yet to be implemented across all countries and territories, and the islands around the Caribbean remain problematic. The evolution of the tax haven problem and its countermeasures will bear close watching.

※1 Although the Bahamas and Bermuda are not geographically within the Caribbean Sea, they are nearby and included in this analysis.

Writer: Mei Hatanaka

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

タックスヘイブンについての理解が深まりました!!

タックスヘイブンがこんなにも大きな問題だとは知りませんでした!もっと関心を持たなくてはならないと感じました。

複雑なタックスヘイブンについてまとめられていてわかりやすかった。

タックスヘイブン問題の改善の動きも知ることができた。