In late June 2020, a man received a phone call while on a plane bound for the United States. With meetings scheduled in America, he abruptly canceled them after the call and had the plane make a U-turn. The man was Hashim Thaçi, president of the Republic of Kosovo in Southeast Europe, and the call informed him that he had been indicted for war crimes. Mr. Thaçi denies involvement, and in mid-July he reportedly submitted to 4 days of questioning in The Hague, the Netherlands. The canceled meetings in the United States were intended to improve relations with Serbia—what will become of them? And what is happening now in Kosovo, a country whose sitting president has been indicted? This article introduces the complex issues facing Kosovo and Serbia.

Kosovo’s president, Hashim Thaçi (Photo: Estonian Foreign Ministry/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

The rise and fall of Yugoslavia

Historically, Kosovo was part of Serbia, and Serbia was part of Yugoslavia. Located in the Balkans, Yugoslavia sat at a crossroads linking Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and the Middle East, and it was influenced by each. There lived peoples of Roman Catholic Christian heritage, Slavic peoples of the Orthodox Christian tradition, and ethnic Albanians. In the 15th century, the region came under the influence of the Ottoman Empire, which had expanded from the Middle East, and Islam spread. As a result, the Balkans became a region where multiple ethnicities and religions coexisted and intermingled. In the 19th century, people lived between—and were influenced by—two empires: Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.

Although the Balkans had not previously had large states, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the end of World War I led to the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). However, as its name suggests, it was a country composed of multiple nations, and the later Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was also a federal state made up of 6 republics (※1). Despite being a federation of multiple republics, Yugoslavia functioned as a single state because it had a strong leader in Josip Broz Tito. After Tito’s death in 1980, nationalism grew within each republic. The economy continued to decline. After the end of the Cold War, Yugoslavia’s debts to Western countries had swelled, and the country stopped functioning as a single state, prompting a wave of declarations of independence.

Croatia, one of the wealthier republics within Yugoslavia, judged that it would be better off independent and, like Slovenia and Macedonia, declared independence in 1991. However, Yugoslav forces led by Serbia, which did not want to let Croatia go, pushed back, and many incidents occurred, including clashes between supporters and police at a football match between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade in Zagreb. Croatia eventually achieved independence from Yugoslavia, but conflict then broke out within Croatia between Croats and Serbs. This conflict lasted until 1995, Serb residents were forced to withdraw from Croatia, and Serb autonomous areas within Croatia came under Croatian administration after a period of UN interim administration. Around the same time, a similar conflict erupted in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia and Herzegovina was home to Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs, and the Bosniaks in particular sought independence. Serbia objected, and after the declaration of independence in 1992, clashes began. The conflict left around 100,000 dead and 2 million displaced. Ultimately, after UN peacekeeping and NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) intervention, in 1995, with U.S. mediation, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Yugoslavia concluded a peace agreement and the conflict was essentially resolved. The only republics remaining as Yugoslavia were Serbia and Montenegro, but unresolved issues persisted within Serbia—most notably Kosovo.

Toward Kosovo’s independence

As noted, Kosovo had been part of Serbia, but in 2008 it declared independence, becoming the newest country in Europe (※1). The path to independence, however, was marked by constant clashes with Serbia. For Serbia, Kosovo was an unresolved issue dating back to Yugoslav times. Like elsewhere in the Balkans, Kosovo was home to multiple ethnic groups, including an Albanian majority and a Serb minority. In 1974, Tito granted autonomy to the Albanian majority—also as a way to check the power of Serbia. After Tito’s death in the 1980s, as elsewhere in Yugoslavia, economic downturn and rising nationalism led to more clashes between Albanians and Serbs. In this context, Slobodan Milošević, then head of Serbia’s presidency, in the late 1980s and early 90s severely curtailed the autonomy Kosovo had enjoyed and pursued policies such as banning the use of Albanian in schools.

In response, Kosovo’s assembly declared independence and engaged in non-violent resistance, but Serbia also pushed to eliminate Albanian self-governance, for example by passing laws ordering the dismissal of Albanians from state employment. Feeling the limits of non-violent resistance, some formed the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and, starting in 1996, began attacks on Serbia. Serbia responded with repression, and the armed struggle by the KLA spread throughout Kosovo and intensified despite Western mediation. The KLA carried out actions so extreme that it was designated a terrorist organization by the United States, while Serbia suppressed the uprising with force without distinguishing between combatants and civilians, creating a humanitarian crisis in which many Albanians fled abroad. In response, NATO launched air strikes against Serbia, but these strikes also hit civilians, rapidly escalating the conflict and producing large numbers of refugees. In 1999 June, Yugoslavia accepted a peace proposal, and Kosovo came under UN interim administration.

Members of the KLA (Photo: Craig J Shell/Wikimedia [Public Domain])

Under UN interim administration, Kosovo increasingly took on the characteristics of an independent state. Political parties such as the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), which included Mr. Thaçi—formerly a key leader of the KLA—and drew on the KLA’s legacy, emerged. The UN interim administration also adopted a constitutional framework for governance, and the first elections were held in 2001. During this period, tensions against remaining Serb residents in Kosovo were high, and in 2004 riots against Serbs resulted in deaths—an incident that underscored unresolved domestic problems. In the 2007 elections, the PDK won and Mr. Thaçi was chosen as prime minister. In 2016, he was elected by parliament to the newly established post of president. Mr. Thaçi declared he would bring about Kosovo’s independence, which was achieved in 2008, but Serbia still does not recognize Kosovo as a state. As of 2020, while 113 countries have granted recognition, Kosovo remains outside the United Nations due to the influence of Russia’s veto power preventing Security Council approval—an unresolved international issue.

International issues surrounding Kosovo and Serbia

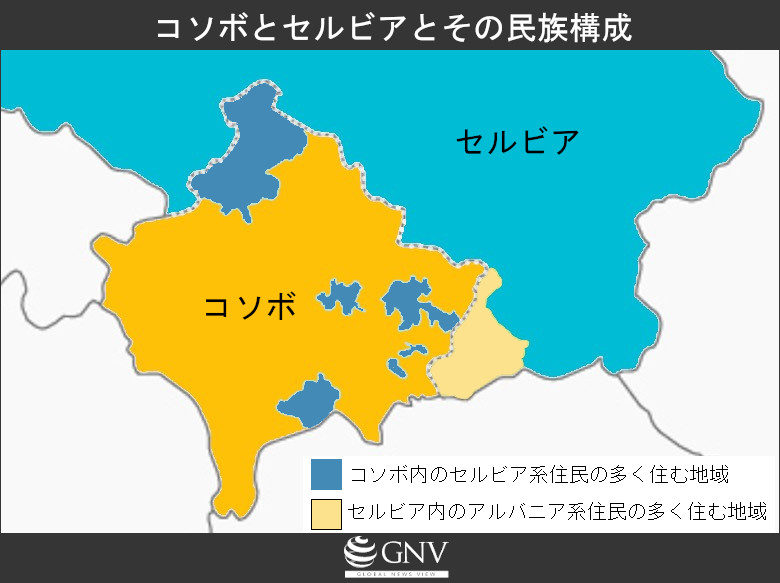

Improving relations with Serbia is unavoidable if Kosovo is to resolve its various problems. From Serbia’s perspective, however, Kosovo’s independence—wrenched away by the armed actions of the KLA and NATO—is unacceptable, and it maintains that Kosovo remains part of Serbia. Kosovo also has significant natural resources, such as zinc, which Serbia is reluctant to relinquish for economic reasons. Furthermore, northern Kosovo includes areas with large Serb populations, and the region holds great importance for Serbian statehood, including the oldest Serbian Orthodox churches and many monasteries—strong historical and religious reasons for Serbia not to give up Kosovo.

Meanwhile, Kosovo has consolidated de facto independence with no sign of returning to Serbia. On the contrary, relations deteriorated as Kosovo imposed a 100% tariff on imports from Serbia, which still refused to recognize Kosovo as a state, to exert economic pressure.

Nevertheless, negotiations between Serbia and Kosovo have recently intensified. Presidents Thaçi and Aleksandar Vučić considered even a land swap between Serb-majority areas in northern Kosovo and Albanian-majority areas in southern Serbia to reduce friction within both states, and the two sides gradually moved closer—eventually reaching the point of direct talks.

Why did the two countries begin to converge? One reason was the EU. Both sought membership in the EU. For their part, EU member states wanted to help resolve the Kosovo issue—geopolitically important—in order to build goodwill with Kosovo, a strategic calculation. The EU succeeded in initiating talks by making improved relations a condition for both Serbia and Kosovo to advance toward EU membership. While bringing both sides—previously only posturing from afar—into negotiations was a significant achievement, the EU’s engagement later stalled as it became preoccupied with internal issues.

The United States took over efforts to improve relations. The Trump administration sought a foreign policy achievement ahead of the next presidential election by helping resolve the Kosovo issue—another calculation. The U.S. appointed Richard Grenell as special envoy on the matter and succeeded in getting Kosovo to lift its 100% tariff on Serbian imports. It continued to press both sides, eventually securing a face-to-face meeting between the presidents in Washington. But, as noted at the beginning, the meeting was canceled when President Thaçi was indicted and returned home.

Not all countries welcome improved relations; Russia does not. Russia has long maintained good ties with Serbia, in part because both have many Slavic people of the Orthodox Christian faith—ethnic and religious similarities. Serbia is also in the Balkans, a region linking the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and a theater for countering Western expansion after the Cold War. For these reasons, Russia has acted as a backer of Serbia.

Brnjak on the Kosovo–Serbia border (Photo: Julian Nyca/Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Domestic issues surrounding Kosovo and Serbia

Although the negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia are entangled in the interests of several countries, both Kosovo and Serbia also face domestic headwinds. In Serbia, public opinion is strongly opposed to Kosovo’s independence. A U.S. think tank’s survey of Serbians in September 2019 found that about 70% believe Kosovo is part of Serbia, and 70% rejected the idea that Serbia “lost” Kosovo because it was defeated in the Kosovo war. As Serbia has become increasingly authoritarian in recent years, it is conceivable that it could force an agreement with Kosovo, but the political costs would be high. President Vučić has also said he will not consent to Kosovo’s independence merely in exchange for EU membership. Specifically, he has set conditions including creating Serbian autonomous structures within Kosovo, granting special status to medieval Serbian Christian churches in Kosovo, and preferential treatment for Serbia regarding resources.

On the Kosovo side, the issue highlighted at the beginning of this article is that President Thaçi was indicted by the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (SPO). Established in 2016 as part of Kosovo’s judicial system to investigate serious cross-border international crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the Kosovo war, the SPO was set up with EU support for its creation process. Mr. Thaçi had been an energetic KLA leader during the 1990s conflict with Serbia, and he now faces war crimes charges including murder, persecution, torture, and organ trafficking.

In fact, even before this indictment, investigations into crimes committed during the Kosovo war faced various obstacles. During investigations by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia into 1990s war crimes, witnesses in cases where KLA fighters were indicted were subjected to violence and intimidation. Although a court to try international crimes committed during the Kosovo war was established 17 years after the conflict, some lawmakers later tried to dismantle or shut it down by changing the law. There were also attempts to influence verdicts, such as sightings of indicted individuals dining with judges. Mr. Thaçi, too, had long been a subject of inquiry, but he evaded and at times obstructed investigations, avoiding indictment, and he has denied involvement in war crimes. To protect witnesses and conduct trials free of domestic pressure, a court has been established in The Hague, Netherlands, where the SPO plans to hold trials. In Mr. Thaçi’s case, investigations are expected to proceed not only into wartime crimes but also into obstruction of these investigations.

Former SPO office (DennisHH/Wikipedia [Public Domain])

Outlook

As we have seen, the issues between Kosovo and Serbia are extremely complex, tied up with history, ethnicity, religion, and more. With the added calculations of Western countries, this is no longer a simple bilateral matter but an international one. The indictment of President Thaçi, which comes just as the two countries had begun to move closer despite external pressures, risks derailing the emerging alignment, and depending on the outcome of the case, significant changes could follow. We will be watching closely how the indictment proceeds and how relations between Serbia and Kosovo evolve.

※1 The Socialist Republic of Serbia, the Socialist Republic of Montenegro, the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, the Socialist Republic of Croatia, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, and the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina

※2 In February 2008, Kosovo’s assembly declared independence from Serbia, and it has been effectively independent since then. As of 2020, it has not yet joined the United Nations, but 113 countries out of the UN’s 193 member states recognize Kosovo’s independence.

Writer: Yoshinao Araki

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi, Mayuko Hanafusa

セルビアと良好な関係を続けてきた日本が、コソボを承認してしまったことは残念な事であり、特筆に値すると考えます。

コソボについて全然知りませんでした。今回の大統領が起訴された件で今までの交渉が水の泡とならないといいなと思いました。今後の動向にも注目したいです。

非常に複雑な問題が分かりやすくまとめられていてよく理解できた。

様々な国や組織の思惑が絡んでいて、簡単には解決できない問題である。

しかし、例えばトランプ大統領は次期選挙に向けてのパフォーマンスの一環で改善を図ったり、EUもコソボに恩を売る目的で改善に繋がる行為を促した。このように関与する国や組織にとって、問題の解決につながる行為にインセンティブを上手く与えることができれば、解決にはつながるのかもしれないと考えさせられた。