A dark shadow covering the sky. Since 2019, there has been a massive outbreak of desert locusts centered on East Africa, spreading to the Middle East and South Asia. In addition, swarms that emerged in Paraguay are spreading across South America. This outbreak is said to be due to heavy rains creating conditions favorable for desert locusts to breed, and it has also been linked to climate change. These swarms are causing severe food shortages for people. The desert locust is called “the most destructive pest in the world”, and a swarm covering one square kilometer can consume enough food for 35,000 people in a day. In Pakistan, as of June 2020, it is said that 25% of the harvest had been damaged. It is also forecast that in 2020, 25 million people in East Africa and 17 million in Yemen will face crisis-level food shortages.

Desert locust (Photo: Max Pixel [Public Domain])

However, problems of food shortages are not limited to locust outbreaks. A complex mix of causes has left hundreds of millions around the world facing food insecurity today. Is such a dire situation being reported? If so, how is it being covered? In this article, after outlining the reality of food shortages, their drivers, and problems in the food system, we analyze media coverage of food issues.

目次

Global overview

There is enough food in the world to feed everyone. Nevertheless, many people still suffer from hunger. According to the report “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020” (SOFI 2020) issued by international organizations such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), approximately 750 million people were in a situation of severe food insecurity (※1) in 2019. This number has been increasing since 2015. By region, Asia had the most at about 422 million, followed by Africa at approximately 249 million. However, comparing prevalence, Africa was the highest at 19%, while Asia was 9%. Comparing by gender, the prevalence was higher among women. Including those in situations of moderate food insecurity, the number exceeds 2 billion—one in four people worldwide. The Global Network Against Food Crises (The Global Network Against Food Crisis) report (Global Report on Food Crisis: GRFC) also indicates that refugee food insecurity is a major problem. It is said that more than half of the world’s refugees are in eight countries (※2), and those countries are in crisis-level food insecurity (※3), with many refugees living under food-insecure conditions.

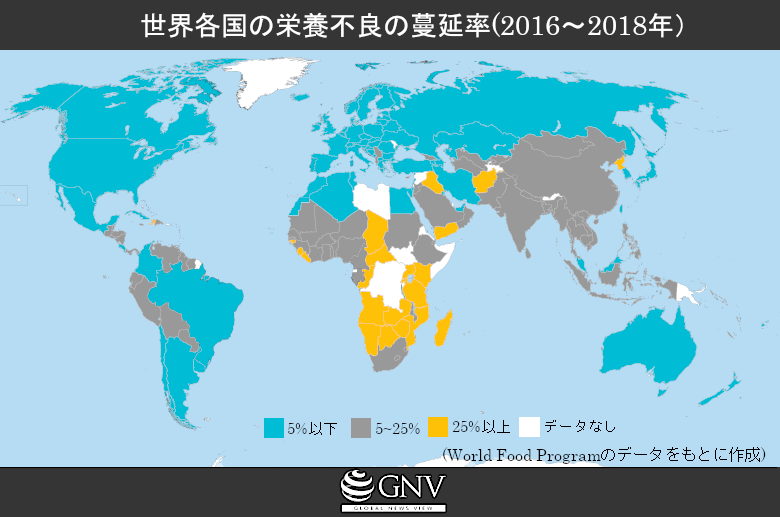

Continuously unstable access to food has also left many people undernourished (※4): in 2019, 690 million people were undernourished, 8.9% of the world’s population. Here again, Africa had the highest prevalence at 19.1%. In Africa, Central Africa in particular reached 29.8%. Undernutrition is said to have a significant impact on children. While the prevalence of stunting among children due to undernutrition fell to one-third between 2000 and 2019, still 21.3% of children under five worldwide are stunted.

Factors behind food shortages

As seen above, food insecurity and undernutrition are severe. Why is this happening? Let’s outline the major factors in recent years. According to GRFC 2020, the most significant factors in 2019 were armed conflict, climate change, and economic crises. Of these, armed conflict was the largest. More than half of people facing crisis-level food insecurity worldwide have been driven there by conflict, and this number increased from 2018. Under conflict, people cannot farm: they are forced to leave their fields, and it becomes difficult to obtain seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Landmines and unexploded ordnance left in the ground can also make it impossible to till the land. Even non-farmers lose jobs or incomes due to conflict, and food prices may soar. As a result, even if food exists, obtaining it becomes difficult.

The next major factor is climate change. Extreme weather such as droughts and floods directly affects crops and livestock, sometimes devastating harvests. Such impacts are especially severe for smallholder farmers, who often lack the funds to recover from climate shocks. For pastoralists dependent on rainfall, the damage from climate change is also grave. Regionally, East Africa has been particularly affected. For example, there were large-scale floods in 2019. These heavy rains and floods are linked to climate change and, as noted at the start, are one of the drivers of the massive desert locust outbreak. In much of Asia, surface runoff from Himalayan glaciers is used for agriculture, replenished each year by glacial growth. Today, however, ice is melting faster than it is replenished, causing a decline in irrigation water. There is also the problem of rising food prices when yields fall.

Drought damage (Photo: Meryll/ Shutterstock.com)

Another major factor, especially since 2019, has been economic crisis. Latin America, including Venezuela, has been particularly hard hit. Inflation and currency depreciation that worsen terms of trade, along with declines in exports and in investment/capital inflows, have taken a toll. Rising food prices and falling incomes can also trigger household- and individual-level food insecurity. Countries with weak governance or ongoing conflict are especially vulnerable to the effects of economic crises.

Beyond these three primary factors, infectious diseases, pests, and sudden natural disasters also play a role. Outbreaks of disease can disrupt people’s livelihoods and affect markets and supply chains. For example, the impacts of COVID-19 are so significant that some say more people may die from hunger caused by its effects than from the virus itself. Beyond the locusts mentioned above, many other pests exist, and pest outbreaks can directly damage crop production. Earthquakes and tsunamis, among other natural disasters, can also damage infrastructure and the environment.

Systemic issues

So far we have discussed direct drivers of food insecurity, but why is food so vulnerable to environmental and economic changes in the first place? The answer lies in problems within the global food system. Below we explore structural factors behind food crises.

Chronic inequality and poverty persist worldwide and are heavily reflected in food security. Beyond that, globalization has interconnected the world’s food systems, contributing to disparities in access to food. As food systems globalized, local production for local consumption decreased, connecting buyers and sellers worldwide. As a result, food prices fluctuate globally. In addition to exchange-rate swings, speculation by wealthy investors also plays a role: large-scale futures trading to make money can move prices. When food prices rise, it becomes even harder for people living in chronic poverty to obtain food. For example, from 2007 to 2008, food prices soared, protests by people suffering food shortages erupted across the globe, and many countries experienced economic and political impacts.

Corn harvest (Photo: United Soybean Board/ Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Another problem is the shortage of subsistence food in low-income countries. In principle, a system in which farmers promote crop diversification, protect soil, water, and forests, and produce food for the producing region is more productive, fair, and sustainable. However, high-income countries, investors, and private companies, drawn by low land and labor costs, have pushed the expansion of commercial agriculture in such countries. While increased exports can bring some economic growth, much of the profit tends to be captured by foreign firms. As production for local consumption declines, food shortages often worsen.

One example is the “New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa,” launched in 2012. This was a joint initiative by the G7 (Group of Seven), 10 African countries, and major agribusinesses from high-income countries, established to invest in African agriculture and improve Africa’s food insecurity. In practice, however, in exchange for increased official development assistance (ODA) and foreign investment, local governments were asked to push policy reforms prioritizing these companies—measures that, rather than easing local food problems, could actually fuel further food insecurity。 Although, amid such criticism, the initiative has gradually faded as a G7-wide program, similar tendencies can still be seen in the policies of individual G7 countries. Moreover, export-oriented crops strengthened in this way are often used for biofuels and livestock feed, leading to a shortage of food for people.

Meanwhile, high-income countries import food yet discard large amounts. According to FAO, as of 2018, food lost between harvest and retail (food loss) accounted for about 14% of the total. In addition, a great deal of food is discarded at the retail and consumer stages (food waste), reaching 30% to 40% depending on the country.

Woman carrying bananas (Photo: Dietmar Temps/ Shutterstock.com)

There is also the problem of the loss of crop varietal diversity. Reliance on a small number of crops makes systems highly vulnerable to climate change and pests, increasing the risk of catastrophic damage. Although humans can eat as many as 30,000 plant species, in practice we consume only about 150 of them. For example, in crops like maize and bananas, only limited varieties are mass-produced in large quantities, a documented reality. One reason for this reliance on a few crop types is the concentration of power among a small number of agribusinesses. The “New Alliance” for Africa mentioned earlier is also relevant: among the policy reforms promoted was the liberalization of corporate intervention in agriculture, making it easier for companies to spread patented seeds.

Analysis of media coverage

We have examined the current state and drivers of food insecurity. How, then, has the world’s food situation been reported? We reviewed international coverage in the Yomiuri Shimbun (morning and evening editions) from 2005 to 2019, extracting articles related to food and hunger, and analyzed their content, countries/regions, and subjects (※5). We found first that there were relatively few articles on food: from 2005 to 2019 there were 363 articles in total, roughly two per month.

By content, the most common articles were on food aid and supply, accounting for 32% (117). These mainly covered food aid from international organizations or other countries to nations suffering food shortages, and the domestic supply of food in countries experiencing shortages. The next most common were articles addressing the reality of food shortages themselves at 30% (108). Others included articles on price increases at 17% (62), and articles on measures other than aid—such as export restrictions—at 12% (44). As for the “Food Day” category, the United Nations designates October 16 each year as World Food Day to encourage reflection on food issues, and the Yomiuri Shimbun published analysis pieces annually on the year’s featured food issues. Articles related to Food Day made up 5% (17). These results show that more articles focused on short-term assistance than on the systemic problems and background drivers of food insecurity.

Next, by region/country: As noted above, Africa has the highest prevalence of severe food insecurity, yet Africa-related articles accounted for only 8% (29.8 articles) (※6). Of those, 26% (7.8) did not zoom in on individual countries, but treated “Africa” as a single unit; most such articles focused on conferences held by the UN or other international organizations. Among articles on individual African countries, short-term food aid accounted for 24% (7.1), while only 17% (5) dealt with food shortages. Asia, which has the next-highest share of people facing food insecurity, accounted for 43% (154.6), the most among regions, but within Asia, India and Pakistan—which face severe food insecurity—each accounted for only 1% (India 2.3, Pakistan 1.3). By contrast, articles on North Korea made up 39% of Asia coverage and 17% overall (59.9), roughly twice the total for Africa.

Who, then, are the subjects of the articles? Here, “subject” was judged based on who the article focused on. For example, in an article on food aid, we classified the subject based on whether greater weight was placed on aid recipients or aid providers. The largest share was those taking measures at 40% (147), and combining those taking measures with those providing aid raised the total to 58% (214). By contrast, those lacking food accounted for 28% (101), and those receiving aid only 4% (16). In other words, rather than strongly highlighting the realities of people suffering from food shortages, many articles focused on the actions of international organizations and high-income countries that provide support and take measures for countries and people experiencing food insecurity.

Issues that go unreported

As shown above, international coverage of food issues is skewed in terms of the countries and subjects covered, and many issues are not reported when viewed by content category. By region/country, there was a focus on North Korea and high-income countries—those thought to have stronger ties to Japan—rather than on regions with the highest shares of people facing food insecurity. Even when food insecurity was reported, articles largely addressed direct, immediate causes, such as sudden disasters, infectious diseases, and conflict. Meanwhile, background factors and systemic issues in the food system received far less attention: there were seven articles on biofuels, three on speculation, one on food loss, and only partial mentions of multiple issues in World Food Day-related pieces. Furthermore, most countries were covered only in the short term; only North Korea saw long-term reporting on food insecurity. Many articles concerned food aid, but focused more on donors than recipients. They did not include content noting that such aid is short-term and does not lead to long-term solutions to food issues; instead, many reported the facts of assistance and measures by international organizations and high-income countries. Articles on price increases existed as well, but many simply reported rising prices and short-term impacts/assistance.

Children eating lunch (Photo: Anna Issakova/ Shutterstock.com)

At the time of writing, in addition to the massive desert locust outbreak, the impacts of COVID-19 and climate change have led the UN to warn that the world faces the worst food crisis in 50 years. In an increasingly globalized world where many countries have low food self-sufficiency, the global food problem is hardly someone else’s issue. If only short-term policies are pursued, the world’s food problems will not be resolved. Fundamental reform of the food system is needed. That is why reporting must go beyond surface-level issues to address the background and root causes.

※1 Here, “severe food insecurity” indicates that “the ability to obtain safe, nutritious, and sufficient food is severely constrained”.

※2 The eight countries are Turkey, Pakistan, Uganda, Sudan, Lebanon, Bangladesh, Jordan, and Ethiopia.

※3 Here, “crisis-level food insecurity” refers to Phase 3 or above in the food security classification used in GRFC 2020 (IPC/CH acute food insecurity phase). Specifically, Phase 3 indicates situations where malnutrition more severe than usual is occurring, or where people can only secure minimal food by depleting essential livelihood assets.

※4 Here, “undernourished” is based on the indicator “prevalence of undernourishment” used for Goal 2, “Zero Hunger,” of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

※5 Counted via the Yomiuri Shimbun online database “Yomiuri Shimbun Yomidas Rekishikan,” covering morning and evening editions published in Tokyo between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2019, and classified as “International.” Among articles whose headlines included the characters “食料,” “食糧,” or “飢,” those using “飢” metaphorically were excluded.

※6 To weight articles equally, when one article covered two countries, each country was counted as 0.5 of an article.

Writer: Maika Kajigaya

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi, Maika Kajigaya

直接的な要因だけでなく、システム上にも問題があって、様々な要因が複雑に絡み合って食料不足に苦しんでいる人が多いということがよくわかりました!

とても興味深い内容でした。

飢餓に苦しむ子供たちに少しでも食糧が届くようシステムの構築、改革を望みます。

グローバル化により地産地消が減っていくというのは面白い視点だなと思いました。世界の食糧問題に関心を持てました

グローバル化の進展が食糧不足を解決するかと思いましたが、外資が入ることでさらに不安定になってしまっているんですね……

地域別で見ると食料問題に関する報道はアジアが4割を占めていると知って驚きました。重度の食料問題を抱えるアフリカなどの地域の報道が少ないというのを知って、報道量だけで事態の深刻度を判断してはいけないなと思いました。

世界食糧計画がノーベル平和賞に選ばれたというニュースを観ました。今後世界の人口増加が見込まれている中で、WFPやFAO含め大きな枠組みでの取り組みが必要になるのは間違いないと思います。このニュースが、食糧問題を多くの人が知るきっかけになればと願います。

1人1人が食べることをもっと真剣に考えなくてはいけない。自分も立ち上がります。 皆に伝えていきます。

食料大事