“The Nile has become a lake, … the Nile is ours.” On July 22, 2020, Ethiopia’s Foreign Minister Gedu Andargachew himself tweeted this on Twitter. The remark relates to the dam being built on the Nile River. The dam is abbreviated GERD from the initials of its name, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. As it nears completion, this dam will be the world’s eighth largest and also Africa’s largest hydropower project. However, it has also become a cause of conflict with neighboring countries such as Egypt.

In early July, it was confirmed via satellite imagery that water was accumulating in GERD. The day before the foreign minister’s tweet, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed issued a statement that the first-year filling target had been achieved, stirring controversy. Why did it cause such a stir? Why is Ethiopia in conflict with Egypt and other countries over the construction of the dam?

In July 2020, GERD began to fill with water (Photo: Hailefida/Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

GERD being built on the Nile River

The Nile River, which flows from south to north along Africa’s east coast, is the longest river in the world at 6,650 kilometers. It flows mainly through Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda, and its basin also includes Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Its tributaries are the Blue Nile, which originates in Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, and the White Nile, which originates in Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake, surrounded by Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The GERD discussed in this article is a 145 m-high, 1,708 m-long storage dam located on the Blue Nile in northwestern Ethiopia near the Sudanese border, with an estimated reservoir capacity of 74 cubic kilometers. There are already several dams on the Nile owned by Egypt and Sudan, but upon completion GERD will be a large-scale dam second only to Egypt’s Aswan Dam in capacity. Construction began in 2011, and as of July 2020, about 74% of GERD had been completed. The construction budget comes to roughly US$4.5 billion, most of it covered by national taxes and government bonds.

Ethiopia’s primary goal in building the dam is electricity. In Ethiopia, where more than half the population lives without electricity, the government claims hydropower from the dam will make it possible to supply electricity to more than 65 million people. Surplus power after generation will be exported to African countries such as Sudan, Kenya, and Djibouti, enabling Ethiopia to become Africa’s largest electricity exporter and to pursue economic growth through foreign currency earnings. The dam’s output is expected to reach its maximum in 2023.

Moreover, Ethiopia has a pronounced disparity between rainy and dry seasons, and this dam is expected to provide a stable water supply to the over 60% of Ethiopians who struggle without sustainable water resources. In addition, as a landlocked country that has not invested as much in fishing as in agriculture, Ethiopia is also expected to use the reservoir to develop its fisheries.

This major national project, a matter of Ethiopian prestige, has also fostered unity that transcends the country’s diverse ethnic groups. The movement has spread on social media, with hashtag campaigns such as #itsmydam and #EthiopiaNileRight; the former is used in other tweets by the Ethiopian foreign minister cited at the beginning of this article. These social media-driven efforts have also generated support across borders.

Egypt’s concerns

Egypt is a country that has developed alongside the Nile since ancient times, relying on the river for 90% of its water supply; of that, about 57% comes from the Blue Nile, which originates in Ethiopia. Consequently, Egypt is concerned that Ethiopia’s construction of GERD will reduce the amount of water available to Egypt. With Egypt’s population still growing, water is a vital resource that holds the lives of its people. There are also concerns that GERD’s construction could reduce storage and hydropower generation at Egypt’s Aswan Dam.

Regarding dam plans on the Nile, Egypt has fiercely criticized Ethiopia, arguing that the Nile’s water rights belong to Egypt in the first place. Looking back in history, in a treaty concluded in 1902 between Ethiopia and Britain, which effectively ruled Egypt and Sudan at the time, the parties agreed to prohibit works or construction that would stop the flow of the Nile, unless there was agreement with the Sudanese government. Ethiopia, however, argues that the dam does not stop the flow of the Nile and therefore does not violate the treaty.

Furthermore, a 1929 water agreement between Britain and Egypt stipulated that Egypt retain veto power over river development that would affect its water use, and a 1959 water agreement between Egypt and Sudan stipulated that, excluding evaporation, the Nile’s annual flow be divided between the two countries. Based on these agreements, Egypt asserts its historical rights to the Nile, but Ethiopia was not a party to either agreement and has contended that they are not binding on it.

Egypt has historically taken a hard line against countries considering dam construction on the Nile. This is reflected in a remark by then-President Anwar al-Sadat, who, after concluding peace with Israel under U.S. mediation in 1979, said, “The only matter that could take Egypt to war again is water.” Even in response to Ethiopia’s current dam plans, Egypt has emphasized resolving the issue through negotiations while also signaling it would not rule out military confrontation.

The confrontation has also produced indirect effects. Ethiopia has accused Egypt of supporting anti-government protests and armed rebellions within Ethiopia, which Egypt has denied. There have, however, been actual moves to export weapons to South Sudan, a neighbor of Ethiopia with which Ethiopia has poor relations. In addition, although no link to the Egyptian government has been confirmed, there have been cyberattacks by Egyptian hackers on Ethiopian government websites. All this suggests how unacceptable Ethiopia’s dam plan is to Egypt.

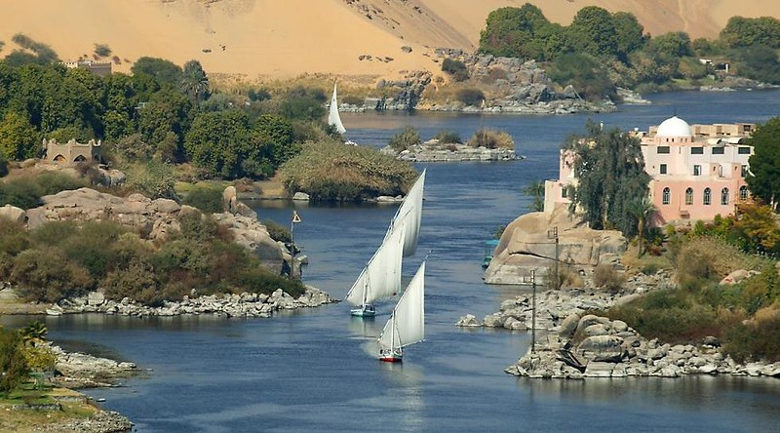

The Nile flowing through Egypt (Photo: Sam valadi/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The impact goes beyond the two countries

Debate over GERD has involved not only Ethiopia and Egypt but also Sudan. This is because the Blue Nile flows from Ethiopia into Sudan and then Egypt, and Sudan, which lies downstream of Ethiopia, cannot avoid being affected by this dam project. Sudan shares a border of more than 1,600 kilometers with Ethiopia and has had disputes with Ethiopia over the border. Under the 1959 water agreement mentioned earlier, Sudan agreed with Egypt to divide the Nile’s waters, and initially opposed the dam’s construction out of concern that it would reduce water supplies.

However, considering the benefits to itself—obtaining electricity from hydropower and avoiding floods by regulating irregular flows—Sudan took a supportive stance and played a role in bridging the divide between Egypt and Ethiopia. In a document Sudan sent to the UN Security Council in June 2020, however, it expressed concern about the start of filling, stating that Ethiopia still had many outstanding issues and arguing that no releases from Ethiopia’s dam should be allowed until a three-party agreement is reached, aligning its position with Egypt.

Moreover, the Ethiopia–Egypt confrontation cannot be separated from the region’s diplomatic context, including North Africa and the Middle East. The region is marked by various rifts over spheres of influence, politics, and religion. In broad terms, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt have aligned against Qatar and Turkey. This rivalry has played out in places such as Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Qatar. Ethiopia has sought to maintain neutrality amid these disputes. Leveraging that neutrality, it has received investment and support from both sides—Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well as Qatar and Turkey. However, with regard to GERD, the more the confrontation with Egypt intensifies, the more difficult it is expected to become for Ethiopia to maintain its previous neutral stance.

Challenges remaining for Ethiopia

Beyond the issues with the countries involved, the GERD project has also been criticized for problems in its planning and operation. Some argue that Ethiopia did not adequately consider the impacts of climate change and changing rainfall patterns when planning GERD, and that compared to past climatic conditions, the project will not achieve the outcomes Ethiopia envisioned, claiming the plans are flawed. There are worries about how much water can be released downstream to countries below Ethiopia on the Nile if precipitation in Ethiopia falls sharply and withdrawals increase beyond normal levels. In the past, there were also criticisms regarding the dam’s size. A prior study argued that Ethiopia’s flow calculations did not sufficiently account for the differences between dry and rainy seasons, that a large reservoir would not fill adequately, and that generation would be limited to about one-third of estimates.

Ethiopian flags displayed around the city of Addis Ababa (Photo: John Iglar/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Financial challenges remain as well. To avoid pressure from other countries and international institutions, Ethiopia has consistently refrained from relying on external financial assistance, but government budgets and issued bonds have not been sufficient. The government therefore sought to have private companies and civil servants purchase government bonds, appealing to patriotism at times and applying pressure at others, with state media playing a role. As a result, many people did buy bonds even if it was financially burdensome. However, the enormous funds spent on the dam project, including cost overruns, have weighed on the economy, leaving the country with significant debt. A key question going forward is how much the dam’s hydropower can invigorate the economy.

Negotiations and the future of the dam

Although the project began in 2011, the basic dynamic has changed little: Ethiopia seeks to push the plan forward as quickly as possible, while Egypt seeks to prevent harm to itself from the dam. That said, Egypt and Sudan have not rejected Ethiopia’s plans out of hand. In 2014 Egypt and Ethiopia signed a document of agreement, and in 2015 the three countries, including Sudan, signed another. These documents recognized the GERD project to the extent that it mitigates negative impacts on downstream countries Egypt and Sudan and uses the Nile’s waters fairly and reasonably.

However, technical studies on downstream impacts were not sufficiently conducted, and talks collapsed in 2017. Specifically, one issue is the length of time needed for reservoir filling: Ethiopia argues it can be completed in just 5–7 years, while Egypt insists it should be estimated at 12 years or more to ease the impact. Other questions include how much flow downstream will be ensured if Ethiopia experiences drought during or after filling, and whether downstream areas will have sufficient water after filling is complete. Egypt is also concerned about impacts on the Aswan Dam, and coordination between the two dams is seen as necessary for operations. On these points, however, Ethiopia and Egypt have remained at odds and have not reached agreement.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia, who has taken a hardline stance regarding GERD (Photo: Stortinget/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In 2020, talks were held in Washington, D.C., mediated by the U.S. Treasury Department and the World Bank, but Ethiopia asserted it had no obligation to seek Egypt’s approval regarding the dam, and the negotiations collapsed. Egypt then brought the issue to the UN Security Council and the African Union (AU), but the final resolution has been left to the three parties involved.

In July, without the consent of Egypt or Sudan for the start of filling, water began to accumulate in the nearly completed dam. Ethiopia stated that the rise in water levels was due to rainy-season precipitation, but the foreign minister’s tweet can also be read as hinting that GERD is beginning operations. No matter how strongly Egypt and Sudan oppose it, once the dam becomes operational, there may be little they can do. The question is whether an agreement acceptable to Egypt and Sudan can be reached regarding its future operation.

The impacts of water scarcity due to climate change and population growth are no longer limited to these countries. We will be watching closely to see how this struggle over “water,” essential for human survival, ultimately plays out.

Writer: Rioka Tateishi

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

周辺諸国との複雑な関係性がよく分かりました!またダムの建設予算の話で、エチオピアが中立の立場をとることから、企業や個人にも国債を買わせることがあるというのは驚きでした。

エジプトとエチオピアが、ナイル川の問題で対立しているという話ははじめて聞いたのでとても興味深いです。ダムができることで国家間の関係性がどのように変わるのか、これからも注目してみていきたいと思いました。

ダムの建設をめぐって、エチオピア・エジプト・スーダンなどが対立していることを初めて知りました。この地域のダム建設をめぐる対立の解決だけでなく、気候変動などによって引き起こされる水不足についても考えなければならないと思いました。

エジプトはナイルの賜物というヘロドトスの言葉を思い出しました。やはり、古くから恵みをもたらすものは、争いの種にもなるものなのでしょうか。