In the 21st century, five new countries have been created: Timor-Leste, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo (※1), and South Sudan. Recently, there is a region that may soon join that list: Bougainville, which currently belongs to Papua New Guinea (PNG). A referendum announced on December 11, 2019 reported a turnout of 85%, with 98% voting in favor of independence, demonstrating how many people fervently desire it. But why was such a referendum held? In this article, we explore Bougainville’s history, how the referendum came about, and the challenges it currently faces.

Bougainville Island surrounded by the sea (Photo: Rapa Nui/pxhere[Public Domain])

目次

Overview of Bougainville

Bougainville is an archipelago of 9,300 square kilometers located at the eastern end of PNG. It includes numerous small islands, and Buka at the northern tip is the political center. PNG is famous for having as many as 853 languages, and even within Bougainville alone the number of major languages is said to be 19. Bougainville is also rich in natural resources such as gold and copper, as well as marine resources. Another characteristic is that Bougainville is a matrilineal society, where land is inherited from mother to daughter and women make key decisions about how land is used.

It is estimated that humans have lived in Bougainville for at least 30,000 years. In physical geography, Bougainville belongs to the Solomon Islands. Because of historical migration and interaction, the two are culturally and ethnically close, and Bougainville has also been called the “North Solomons.” In modern times, however, Bougainville became a colony of several countries and was separated from the Solomon Islands for administrative convenience. The Solomon Islands became British territory, while Bougainville, as part of PNG, first became German territory. PNG, including Bougainville, was under Germany from 1885, then occupied by Australia at the outbreak of World War I, and after the war remained under Australian administration by mandate of the League of Nations. In 1942 during World War II, Japan invaded, and the Allies landed to counterattack, turning the island into a fierce battleground. After the war it returned to Australian rule until PNG’s independence in 1975. At the time of PNG’s independence, Bougainvillean politicians sought separate independence from PNG as the “Republic of the North Solomons,” but failed to gain international recognition and the following year, in a compromise with a UN proposal, became part of PNG.

Before PNG’s independence (–1975)

Bougainville’s modern history is closely tied to mineral resources. The existence of Bougainville’s copper deposit became public for the first time in April 1964, when PNG was still under colonial rule and the Australian mining firm Conzinc RioTinto (CRA) conducted exploratory drilling. As CRA’s team began taking samples of low-grade iron ore, local residents grew alarmed at the prospect of losing ancestral land. Police began visiting the copper site frequently to pressure them, prompting the formation of resident groups and political parties in opposition. A seminary student group criticized large-scale development in Bougainville in a magazine called “Dialogue,” addressing the administration. There were also unofficial referendums on independence, and on the basis of those results, moves to demand an official referendum or a right to self-determination from Australia.

Moreover, negotiations were conducted between the colonial PNG government and CRA under Australian law, with little consultation with Bougainville residents, and in 1967 an agreement called the “Bougainville Copper Agreement” was concluded, causing a major stir on the islands. As a result of these talks, the copper operations in Panguna, Bougainville, began in 1972. The way land for the mine was taken also shows how residents were disregarded. As one example, despite land ownership being matrilineal, the official who came from Australia to negotiate acquisition mistakenly attributed rights to men. Facing the ultimate necessity of abandoning ancestral lands, one woman testified in despair that she would rather be crushed under the company’s bulldozers along with her children.

For Bougainville, the allocation rate of profits was completely unacceptable. CRA took most of the profits, the colonial PNG received only 1.25%, and of that, Bougainville received just 5%. In other words, US$625 out of every US$1,000,000 in profits. While these funds helped build some infrastructure, they also created many problems such as widening inequality, environmental destruction, and low wages for workers. In the end, one could say patience snapped at the exploitation of Bougainville’s golden goose: the copper deposit.

Amid this turmoil, after operations began by Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL), a subsidiary of CRA established in 1967, the Panguna mine produced results beyond expectations. For the first three years of operation, it accounted for about one-third of PNG’s GDP and more than half of its export earnings. Because the Bougainville Copper Agreement was criticized from the start as overly favorable to BCL, it was reviewed in October 1974 and PNG’s take was raised from 1.25% to 20%. But that still amounted to only about 1% of the wealth generated by the mine, and the benefits did not necessarily reach the islanders. As a result, criticism focused on the PNG government, escalating the separatist movement.

Part of the former Panguna mine buildings (Photo: madlemurs/Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

The conflict after PNG’s independence

In September 1975, just before PNG itself achieved independence from Australia, Bougainvillean activists declared unilateral independence as the Republic of the North Solomons. The most influential Christian churches in Bougainville officially supported the declaration, and most islanders welcomed it. However, when PNG’s first prime minister, Michael Somare, froze the assets of the North Solomons region, the republic’s leaders were isolated and became economically and politically exhausted. Six months after the declaration, talks were held between the two sides, and the separatist movement came to an end with recognition of an autonomous government for the region within a province.

Bougainville’s independence movement quieted from 1977 for about a decade. However, it was rekindled by a proposal in the 1987 PNG general election by Father John Momis, a candidate from the Bougainville district, that 4% of BCL’s total sales should be returned to islanders. The following year, in 1988, Francis Ona, a surveyor for the mining company and a representative of the mine area, built on Momis’s stance and demanded a massive K10 billion (about USD 2.8 billion) as compensation for the looting of property and environmental destruction. In November of that year, Ona led the founding of the anti-government Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and attacked government facilities, plunging the islands into a decade of guerrilla warfare known as the Bougainville Crisis. In 1997 during this period, the PNG government attempted to hire foreign mercenaries to suppress the insurgents, but the plan was leaked to the media, forcing Prime Minister Julius Chan to resign in the so-called Sandline incident.

The government declared a state of emergency soon after the crisis began, and the Australian government provided the PNG government with US$200 million in military aid. In May 1989, the Panguna mine—which for 17 years since opening had accounted for about 44% of PNG’s export earnings—was shut down after anti-government forces destroyed mining equipment and blew up power facilities. In response, the government blockaded Bougainville by sea and air, cutting off supplies of essentials to the islands and leading to widespread hunger and disease. It is said that of the island’s 200,000 residents, between 15,000 and 20,000 civilians lost their lives, and 40,000 were displaced. Even after the conflict, trauma has led to incidents of alcohol and drug abuse and crime, and residents have been reported to suffer from mental health problems.

PNG soldiers (Photo: Nick-D/Wikimedia[Public Domain])

Toward peace

Ceasefires and proposals put forward in peace talks during the Bougainville Crisis did not bear fruit, and in May 1990 BRA leader Francis Ona declared unilateral independence for the Republic of Bougainville. However, as the island’s economic situation deteriorated, the first round of peace talks with the PNG government was held in July of the same year. There, the PNG government pledged not to use military force and to resume the provision of essential services for Bougainvilleans such as education, health and sanitation, and communications.

In January 1991 the second round of peace talks was held, and the Honiara Declaration on peace, mediation, and restoration was adopted in Honiara, Solomon Islands. It stipulated that implementation would be reviewed every six months and that the arrangements could be voided if necessary. The PNG government was also asked to continue providing administrative services to restore Bougainville’s devastated socioeconomic life.

The third round of talks planned for July that year was repeatedly postponed and ultimately never took place. One reason was that both sides failed to implement the Honiara Declaration, rendering it hollow. Even so, negotiations resumed in 1997, and the United Nations ceasefire monitoring group began operating in Bougainville. A ceasefire was signed in 1998, and three years later in 2001, the “Bougainville Peace Agreement” mentioned at the outset was concluded, finally bringing the conflict to an end.

A polling station during elections (Photo: Commonwealth Secretariat/Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

The Bougainville referendum

The “Bougainville Peace Agreement” incorporates three key elements: autonomy, a referendum, and a weapons disposal plan. Regarding autonomy, under the Constitution of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville completed in 2004, the region can control broad powers, functions, and resources, including recognition of a government, legislature, and courts. As part of this, the office of president was created and presidential elections have been held since 2005. Regarding the referendum, an independence vote was to be held within 15 years (by June 2020) of the election of the first Autonomous Bougainville Government. As for the weapons disposal plan, it provided for the phased destruction of arms as soon as feasible.

Based on this agreement, a referendum was held in 2019. Conducted over two weeks from November 23, it ultimately saw a turnout of 85%, with 98% (176,928 people) voting for independence and fewer than 2% (3,043 people) voting to remain with PNG. However, the result does not mean Bougainville can become independent immediately. Ratification by PNG’s parliament, which holds the final authority, is required, after which negotiations with the Bougainville government must be concluded before independence can finally be achieved. The PNG government is unlikely to want to set a precedent for losing part of its territory, so the process is expected to be difficult, and some predict it could take more than ten years. Indeed, for now the PNG government is not taking an enthusiastic view of Bougainville’s independence.

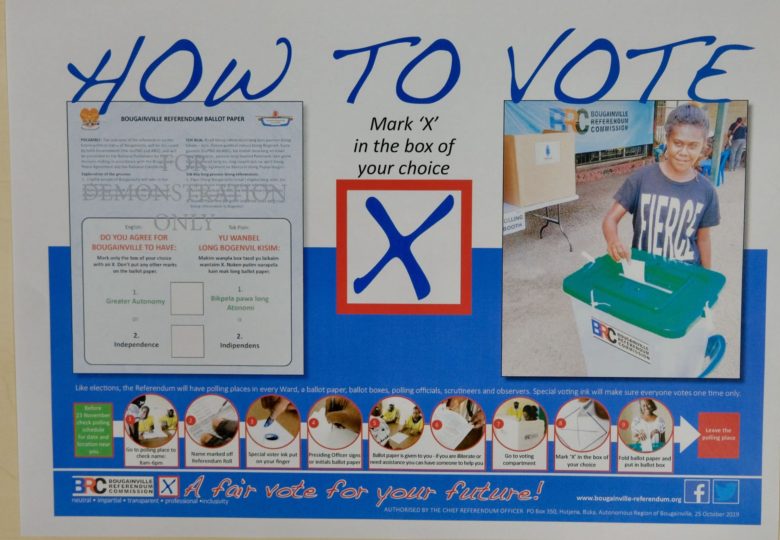

Referendum poster (Photo: Nick Potts)Can Bougainville become independent?

So does Bougainville have a sufficient economic base to become independent? Unfortunately, the answer may have to be no. The Panguna mine has been closed since 1989, and Bougainville is still generating only 56% of the revenue deemed necessary for self-reliance under the peace agreement. Support from stakeholders such as PNG and Australia is therefore essential. Relatedly, there are rumors that China, competing with Australia for influence, has offered investment in Bougainville’s mining, tourism, and agriculture sectors.

The most difficult issue is what to do about the Panguna mine. Bougainville is blessed with minerals such as copper and gold, but nothing is thought to bring wealth on the scale of Panguna. The question has been a major focus in the 2020 elections in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, but deciding whether or not to reopen is far from easy. For now, more than a billion tons of mine waste continue to flow from the closed site, polluting rivers to this day. As a result, reports say residents around the mine are suffering health impacts such as diarrhea and skin lesions, and the situation has been called an ongoing human rights disaster. For this reason Rio Tinto (the CRA mining company renamed in 1995) was the subject of a complaint to the Human Rights Law Centre in 2020, arguing it should be held responsible for human rights abuses in Bougainville.

Studies to reopen the mine are ongoing, but construction costs for restarting operations are estimated at US$4–6 billion, and even in the best case, reopening would not be possible until 2025. Despite these risks, it is estimated that 5.3 million tons of copper and 550 tons of gold remain, worth about US$58 billion. Public opinion is divided. Some argue that reopening would bring prosperity and enable advances in education and health, while others say that considering the environmental destruction and human suffering to date, the plan should be halted—a view also held by many.

Thus, while full economic self-reliance is difficult under current conditions, there are brighter prospects in other sectors. Beyond mining, Bougainville already has other income sources such as fisheries and cocoa plantations. It accounts for 30% of PNG’s fish catch, generating US$10–30 million annually. Bougainville is also an exporter of high-value marine products such as beche-de-mer (dried sea cucumber), recently revived. A variety of industries, including small-scale gold mining, are taking off and could contribute to Bougainville’s economic independence.

[caption id="attachment_12524" align="alignnone" width="780"] A boy looking out over the strait in Buka, a town in Bougainville (Photo: Antman!/ Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

A boy looking out over the strait in Buka, a town in Bougainville (Photo: Antman!/ Flickr[CC BY-NC 2.0])

As the analysis above shows, although the referendum reflected the popular will, the road to independence will be long, and with respect to the Panguna mine, the pros and cons are closely balanced, so plans will need to proceed cautiously. With pressing issues such as sustainable development to address environmental problems, policies to fully guarantee educational opportunities, and tackling mental health, attention will be on what steps are taken next.

※1 In February 2008, Kosovo’s parliament declared independence from Serbia, and it has effectively functioned as an independent state. As of 2020 it has not yet joined the United Nations, but 92 of the UN’s 193 member states recognize Kosovo’s independence.

Writer: Koki Morita

Graphics: Yow Shuning

ブーゲンビルの鉱山のことを全く知らなかったので勉強になりました!

独立後のことを考えると、必ずしも独立できればいいというものでもないと思い、難しい問題だなと思いました。

大多数の人が独立を望んでも、様々な問題からすぐに実行には移せないという現状について詳しく知ることができました。