According to an announcement by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2020 (April), the number of countries that implemented school closures due to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) reached 191. At its peak, about 1.5 billion children, or 91% of students worldwide, were unable to attend school. In response, countries rapidly accelerated the introduction of online classes. However, for various reasons—such as inadequate internet access in low-income countries and impoverished regions, and even in some households in high-income countries—many children have been unable to receive sufficient instruction, widening educational disparities.

These global education issues, including widening educational disparities, did not arise only recently; many problems have been piling up for a long time. How much do the media cover these issues, and how do they report on them? This article analyzes the state of education and its coverage in the media, and explores how education reporting should be.

A child writing answers on the blackboard at a school in Iraq (Photo: U.S. Air Force, Mike Buytas / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

目次

Children who cannot attend school

First, let’s look at the current state of education around the world. In 2015, the United Nations Summit adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), naming “Quality Education” as the 4th goal. As Target 1, it set the objective to “ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes by 2030.” Unfortunately, with 10 years remaining until 2030, it has become clear that the likelihood of achieving this goal is extremely low. To achieve completion of lower secondary education (middle school graduation) for all children, all children worldwide needed to have entered primary school by 2021, and for completion of upper secondary education (high school graduation) by 2018. However, as of 2018, it was reported that about 260 million children aged 6 to 17—about 1 in 5 globally—were out of school. In particular, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest out-of-school rate in the world at approximately 32.3%, with around 97 million children unable to attend school.

Children attending class at a school in Indonesia (Photo: piqsels [Public Domain])

Gender disparities in education are also a major challenge. Currently, the number of boys aged 6 to 17 who are not receiving education is about 131.3 million, approximately 17.2% of all boys in that age group worldwide, while the number of girls is about 131.7 million, approximately 18.5% of all girls—seemingly not a large difference at first glance. However, looking by region, in Central Asia the out-of-school rate is about 6.8% for boys versus about 8.4% for girls; in Northern Africa and Western Asia, about 15.4% for boys versus about 18.8% for girls; and in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 29.6% for boys versus about 35.1% for girls, revealing clear disparities. In this way, compared with high-income countries, disparities are more pronounced in low-income countries, and approximately one-third of primary schools have not achieved gender equality.

Why, then, are so many children unable to attend school? The first reason is poverty. Children from poor families work or help with housework instead of going to school in order to support the household. This is not simply a matter that can be solved by making school free. Even if tuition is free, families still need money for textbooks and uniforms. Even when children manage to attend school, there are statistics showing that children from the poorest households miss school up to four times more than those from the wealthiest households. In addition to work and housework, this may be due to poor living environments and inadequate nutrition, which make them more susceptible to illness. For various reasons, children in poverty are unable to study sufficiently.

A girl working instead of going to school in Nepal (Photo: Shresthakedar / Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

The second reason is a shortage of schools. Especially in low-income countries, the number of schools is overwhelmingly insufficient relative to the number of children. As a result, many children cannot attend because schools are too far away or the mountain paths on the way are too treacherous. However, simply increasing the number of schools does not solve the problem. Low-income countries also face teacher shortages and funding shortfalls, making it impossible to immediately operate schools even if they are built. To eliminate the shortage of schools, multiple issues must be addressed simultaneously, and the road ahead is long.

A third reason is conflict and the accompanying insecurity. Around the world, there are many cases where children cannot attend school safely due to conflict, and many countries and regions have schools that are closed as a result. Currently, the situation is so serious that 1 in 100 people worldwide is a refugee or internally displaced person, and about 40% of them are children. In Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria—countries where conflicts persist—a total of 9,272 schools had been forced to close as of January 2019. In the Sahel region of West Africa, multiple conflicts have been intertwined across borders since around 2011, keeping the situation tense. In particular, since around 2017, attacks targeting schools and children have increased, leading to a sharp rise in school closures. In this way, children around the world are unable to attend school for a variety of reasons.

Issues surrounding the quality of education

Even when children can attend school, the quality of education varies greatly by country and region. It is estimated that about 617 million children worldwide do not meet minimum proficiency standards in reading and mathematics. In particular, the share of children without sufficient literacy skills is the worst in the world in Sub-Saharan Africa at about 88%, and very high in Central and Southern Asia at about 81%, making improvements in education quality an urgent task. There are also data showing that 60% of the world’s population without sufficient literacy skills are women, indicating that gender disparities exist in education quality as well.

A child attending class at a primary school in Ethiopia (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Why, then, does the quality of education vary? A primary reason is the shortage of teachers. There are statistical estimates that to achieve the SDGs, the world will need to hire about 69 million new teachers, and from the perspective of teacher shortages as well, achieving the SDGs is considered difficult. In low-income countries in particular, there is not enough budget to hire the required number of teachers, forcing instruction to be carried out with too few teachers. Moreover, many of these few teachers are unqualified due to a lack of proper training, making it difficult to deliver high-quality lessons.

In schools in low-income countries that suffer from poor infrastructure, necessary facilities such as classrooms are also lacking. As a result, measures such as holding classes with as many as 80 students in a single classroom or operating in two shifts (morning and afternoon) are taken. However, this creates a dilemma: the time that can be devoted to each student decreases, increasing the number of children who cannot acquire necessary skills.

Of course, poor education quality is not limited to low-income countries. For example, in Indonesia, low government spending on education and the challenge of balancing education and religion have contributed to declining quality. In addition to achieving gender equality, issues such as the lack of women’s autonomy and female genital mutilation (FGM) are expected to improve through the spread of sex education, but the current state remains far from sufficient. There are many challenges to be addressed.

A school in Dho Tarap village, Nepal (Photo: Sergey Pashko / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

However, it is not all negative. There are countries that spend heavily on public education and have worked enthusiastically on education policies. In Finland, for example, various measures have been implemented to raise educational standards, such as curriculum liberalization and requiring teachers to hold a master’s degree. There are also countries like Poland that have built world-class education systems and achieved remarkable growth. While not at the national level, there have also been noteworthy developments such as the creation of low-cost teaching materials that can be used in low-income countries.

Biases in the content of education reporting

So far, we have looked at the current state of education in the world and its major challenges. How, then, has education around the world been reported? This time, we examined articles related to education from among those covering international news in the morning edition of the Mainichi Shimbun over the 5 years from 2015 to 2019, analyzing their content and the countries/regions covered (※1). The results showed that there were few articles on education itself: a total of 172 articles over 5 years—fewer than 3 per month. Was there any bias in their content? The graph below classifies all 172 articles according to their content (※2).

The most common category was “incidents,” including mass shootings and terrorist attacks at schools and the abduction of students, accounting for 22.3% of the total. Articles corresponding to “protests,” such as those covering demonstrations or strikes involving students and student-led movements, were the second most common at 16.9%. Articles related to “study,” such as school lessons and textbook content, and study abroad, accounted for 12.8%, followed by “society”-related pieces focusing on students and their parents/guardians—such as tuition and student support—at 10.5%. “Politics” accounted for 9.6%, and “policy” 8.4%. In this analysis, articles in the “politics” category included content such as interactions between students and presidents and election features in which education was a theme; “policy” included articles on each country’s education policies and on policies directly related to students and schools, distinguishing the two categories accordingly.

As the graph shows, coverage of “events,” such as incidents and protests, makes up about 40% of the total. There are two major reasons for this. First, mass shootings and demonstrations have impact. Not limited to education-related reporting, the media have a tendency to focus on events. It is believed that reporting an event attracts more reader interest than simply addressing chronic issues.

Furthermore, incidents and protests involving students and schools differ in character from other incidents and protests. The media consider that mass shootings at schools, where children are the targets, stand out in their tragedy and elicit greater sympathy than shootings occurring outside schools. The same applies to demonstrations. For this reason, events involving schools and students tend to be covered extensively. In addition, articles on politics and policy together accounted for 18%, indicating that reporting has a tendency to focus where power is concentrated.

On the other hand, there were almost no articles touching on long-term education issues like those mentioned earlier. Of the 172 articles, there was only one that reported on the global reality of children unable to attend school, one that covered a UNICEF school-building project in Burkina Faso where school enrollment is low, and one that reported on school closures in conflict-ridden West Africa. There were no articles in these five years that focused on the current situation in low-income countries—where education problems are most severe—or on gender discrimination. This embodies a problem in reporting: issues are not covered unless there is a triggering event. Moreover, not limited to education, the lack of coverage of low-income countries itself is a major factor.

Bias in reporting volume by country

Next, let’s look at the trends in the countries that are covered. Among the 172 articles counted this time, a total of 43 countries appeared. The graph below shows the top 10 (11 countries in total because Iraq and Iran are tied for 10th). On the far right is a bar indicating the share of international education coverage devoted to Japan.

As is immediately clear from the graph, articles about China and the United States are overwhelmingly numerous, and together with South Korea, the top three countries account for more than half of the total. China saw a surge in articles due to the protests in Hong Kong, and the United States due to mass shootings. Looking at the categories, 82.8% of the politics-related articles were about China, the United States, or South Korea. While the top three countries receive special features with every election or summit meeting, other countries receive little attention. Among the total of 17.3 articles that mentioned Pakistan, Nigeria, or Bangladesh, 72.2% were related to some kind of incident; the remaining articles were mostly about the underlying society or religion, and only one article—about girls’ education in Pakistan—referred to study. All articles about Iraq and Iran fell into one of the categories of society, religion, or study. This shows that there is a very large bias by country in the fields that are covered.

There were also 9 articles about Taiwan, all written in the two years of 2015 and 2016, and more than half of them were about the textbook revision issue. Of the five articles about North Korea, all but one concerned the detention of an American student. As this suggests, even when the number of articles is large, many cover the same subject, making it difficult to say that coverage is well balanced.

The significance of reporting on “education”

As we have seen, there are significant biases in international reporting on education—the countries covered and the topics chosen—and long-term, large-scale problems have been neglected. Yet the truth often lies in the parts that are not reported. Finally, let us consider what reporting brings us and the significance of reporting on “education.”

Children in India attending a lesson while sitting on the ground (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

First, one significance of education reporting is that, by covering large-scale issues in education—not just rare, eye-catching events such as incidents and protests—it provides people with opportunities to learn about the state of the world. Even without astonishing events or little-known discoveries, continuing to report on large-scale issues—such as the hundreds of millions of children who cannot access education—has value. If this helps people better understand the current state of education and prompts them to look at the underlying issues of poverty, conflict, teacher shortages, and infrastructure deficits, that alone is sufficient justification for reporting.

Second, reporting on changes in education can help people recognize global progress while simultaneously highlighting new problems. The effects of policies and changes in literacy rates are long-term and may appear to change little over days or months. However, no matter how gradual, trends can be discerned. For example, the key reports published by UNESCO should always contain noteworthy changes worthy of coverage. Whether deterioration or improvement, those changes reflect the current state and dynamics of the world. Change is a mirror of the world. Therefore, we need to focus not only on sudden events but also on gradual yet significant changes.

Third, this reporting can serve as a catalyst for solving the various challenges in education. First, if the many educational issues mentioned earlier are reported, public interest in global education will grow and public opinion will form, which should support measures by international organizations, governments, and NGOs. Support for these measures and donations will likely increase as well. Second, education reporting could also lead to measures addressing the poverty that underlies these issues and the factors that exacerbate it. Of course, high-income countries are not bystanders, given that they have contributed to extreme poverty through issues such as illicit financial flows and unfair trade. They have a responsibility to report and to act. Recently, coverage related to the SDGs has been on the rise, but regarding education, reporting on the crucial matter of “achievement,” such as prospects and methods for achieving goals, remains limited. More in-depth reporting is needed to mobilize public opinion and spur action.

Fourth, we should also mention the significance of reporting positive news. Education news is not only dark; there are many positive stories, and these too have value. If innovative education initiatives around the world—regardless of scale—are covered by the media, other educational institutions may follow their example. Reporting such efforts may lead to improved education quality not only in the countries covered but ultimately across the globe.

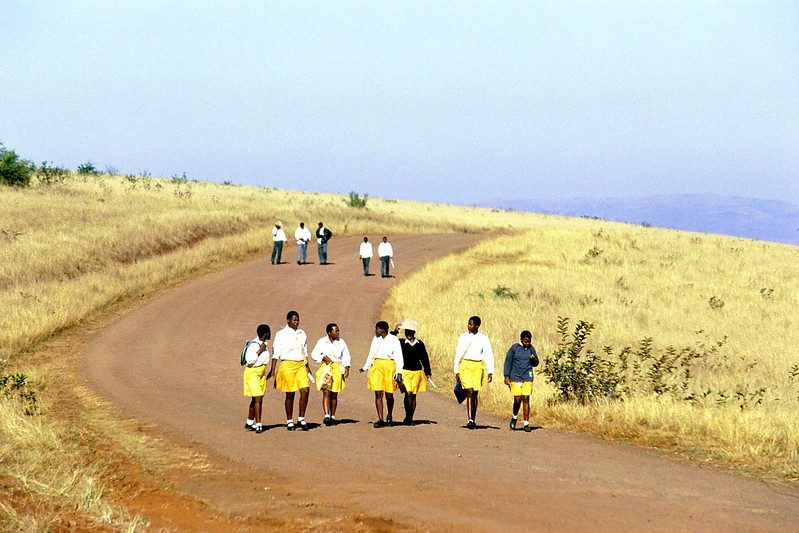

Children attending school in South Africa (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

“Education for All.” Adopted at the “World Conference on Education for All” in 1990, this was a UNESCO-led initiative aiming for everyone in the world to be able to read, write, and calculate by 2015. Although it achieved certain results, it unfortunately was not fully achieved. Even so, until the day when all children can naturally receive an education, we must not abandon this slogan of “Education for All.” If all children receive equal access to quality education, many more will acquire the skills needed for life. That will help lift them out of poverty and serve as a first step toward a more gender-equal world. For this reason, the challenges in education are serious issues that must be addressed by the entire world. However, everything starts with “knowing.” Nothing can begin without understanding the current situation. Now, with so many issues piling up, may be precisely the time to rethink how we report on education.

※1 Using the Mainichi Shimbun online database “Mainichi Shimbun Mai-saku,” we counted only the international pages of the morning editions published in Tokyo from 2015/1/1 to 2019/12/31. Articles were included if the headline or body contained “education,” “student,” “school,” or “high school,” excluding those without full-text display or those clearly unrelated to education based on the headline.

※2 To count each article equally, when a single article dealt with two themes or countries, each was counted as 0.5 of an article. For example, if one article covered both politics and society, it was counted as 0.5 for politics and 0.5 for society.

Writer: Kyoka Maeda

Graphics: Kyoka Maeda

で?なんでウイグル再教育についての話題はこのサイトに二行しかないの?既存メディアのアンチテーゼとしてやっているんなら、それこそやるべきだろ。何故今ここにある民族浄化、中国の傍若無人で悪逆な弾圧を見過ごしているのか納得のいく説明を求める。

「GNVについて」のところにもあるように、GNVは「報道されない世界」に関する情報・解説を提供しています。日本では報道されていない、もしくは報道量が極めて少ない国、地域、出来事、現象を中心に情報を発信しています。その方針について詳しくみるにはこの記事 //globalnewsviewdotorg.wpcomstaging.com/archives/10730 も参照にしてください。朝日新聞、毎日新聞、読売新聞、いずれにおいても、中国はアメリカに続き常に2番めに報道量の多い国です。また、過去1年の報道を検索すれば、「ウイグル」が含まれる記事は:朝日新聞71記事、毎日新聞89記事、読売新聞117記事です。ウイグルの問題は深刻ではあるが、報道されていない問題ではありません。

コメントありがとうございます。私はウイグル自治区における職業訓練施設の問題について、BBCやAFPBBなどの海外報道機関の日本語版の報道は多いですが、国内メディアではそうではないと認識しています。国内メディアのそれについても報道されていない訳ではないにしても、その絶対量が少ないと考えており、この日本メディアの消極的な姿勢は好ましくないと考えています。重ね重ね返信の程ありがとうございました。

それからその「ウイグル」が含まれる記事というのはasahi.comなどのウェブサイトで「ウイグル」と検索を掛けて出てきた数字と認識していますが、これをそのまま載せていますか?それとも紙面掲載記事のみの数字ですか?少し探しても見当たらなかったので、お答えいただければ御幸甚に存じます。

「国内メディアのそれについても報道されていない訳ではないにしても、その絶対量が少ないと考えており、この日本メディアの消極的な姿勢は好ましくないと考えています。」

同感です。この問題の背景には国際報道全般の少なさがあります。新聞、テレビ、オンラインメディア、どれを取り上げても国際報道は全体の10%程度で、おおげさにいえば情報鎖国状態です。その中では中国に関する報道ははまだ多い方(2位)ですが、絶対量は少なく、その中でのウイグル問題に関する報道も問題の規模の割に少ないのも事実だと思います。

上記であげた「ウイグル」を含む記事数ですが、各紙が出している有料データベース(聞蔵IIビジュアル、毎日新聞 マイ索、読売新聞 ヨミダス)から検索(過去1年分の全国版)したものになっています。デジタルではなく、紙面です。

世界に目を向けてもらうように日本のメディアに働きかけるのがとても大切だとGNVで考えております。

返信の程ありがとうございました。確かにヨミダスだの聞蔵だのといった記述は以前見たことがあるかも知れません。教えていただきありがとうございます。

世界の教育の現状から、報道することの意義までくわしく丁寧にまとめてあり、とても読みやすかった。国際的な取り組みが行われているにも関わらず、現実はなかなか成果が現れないことにやるせなさを感じた。報道が少しでも社会の動きにつながることを願う。

教育を無償化すればよいだけではない、教育を妨げる様々な要因について考えることができました。

教育について話がすごくまとまっていて、個人的にとても好きな読みやすい記事でした。

教育は様々な社会問題の根幹ともなっていると思うので、この記事を読んで改めて、教育についてより包括的にかつ長期的な目線で報道されていくと良いなと思った。

カンボジアなどで学校を作ろうというボランティア活動が日本ではよくあると思うのですが、学校をただ増やすだけではだめだという意見も聞いたことがあります。学校を増やすだけでなくさらに何を心がければいいと思いますか。

コメントありがとうございます。確かに、教師不足やインフラ不足を抱えている国・地域では、学校を建てるだけではすぐに運営することは困難だと言えます。例えば、教師不足を解消するために教師育成プログラムを実施したり、教育の質を少しでも向上するために低所得国でも使えるような低価格の実験キットを開発・寄付するなど、その背景にある根本的な問題に目を向けるとよいのではないかと思います。