On May 4, 2020, information that “a coup had occurred against the Emir of Qatar” became a hot topic on Twitter. A video claiming that gunshots were heard in the coastal city of Al Wakrah, Qatar, was retweeted by about 12,000 Twitter accounts. However, in reality, there was no coup, and it was revealed to be fake news. There are suspicions that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) may have been involved in the background of this incident. 3 years on from the start of the Qatar crisis, could this be a continuation of that event? In this article, we will trace the diplomatic relations in the Middle East and North Africa behind the Qatar crisis and the situation after the crisis erupted.

Doha, the capital of Qatar, seen from above (Photo: marc.desbordes / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

目次

Qatar’s history and the road to the crisis

Qatar became independent from the United Kingdom in 1971, September. The small country, which had a population of only 200,000 in 1980, underwent significant development after Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani seized power in a coup in 1995 and began to act energetically. In addition to the oil sector that had already been under development, Emir Hamad began developing natural gas, and Qatar grew economically. As Qatar became wealthy through the oil and natural gas industries, it needed a low-wage workforce. Like other Middle Eastern countries, it began accepting large numbers of immigrants, mainly from India, Pakistan, and Nepal, and by 2019 they accounted for 70% of Qatar’s population of about 2.78 million. Furthermore, immigrants make up as much as 94% of the workforce, according to results. In 2013, there was a generational change from Hamad to Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, and Emir Tamim, at 33 years old at the time, became the world’s youngest monarch.

So how has Qatar historically interacted with its neighboring countries? Qatar has long tended to depend on Saudi Arabia in terms of size and location, joining Saudi-led military interventions. In fact, Qatar intervened militarily alongside Saudi Arabia in 2011 in Bahrain and in 2015 in Yemen. Beyond the military sphere, economically, Qatar relied on its Persian Gulf neighbors, led by Saudi Arabia, for food imports. However, to protect itself from that influence, Qatar embarked on its own foreign policy.

In the first place, because Qatar shares one of the world’s largest natural gas fields with Iran, it needed to build friendly relations with Iran. The Saudi government, however, perceives Iran as a threat. In other words, Qatar’s forging of friendly relations with Iran also created friction with Saudi Arabia. At the same time, to avoid overreliance on Saudi Arabia, Qatar also deepened its dependence on the United States. Qatar hosts the Middle East’s largest U.S. military base, which served as a key staging point during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

When the phenomenon known as the “Arab Spring” spread across the Middle East and North Africa in 2011, Qatar’s stance and response differed greatly from Saudi Arabia’s. The reason lies in the two countries’ differing views of the organization known as the “Muslim Brotherhood.” The Muslim Brotherhood is an organization that promotes an ideology based on Sharia across countries in the Middle East and North Africa. It is a powerful movement opposed to monarchies and enjoys grassroots popularity. Its activities are wide-ranging, including social welfare, and its influence on the public is significant. Saudi Arabia and the UAE view the Muslim Brotherhood as a threat to their own monarchical and authoritarian systems. On the other hand, Qatar has been seen as supporting the Brotherhood, expecting that cooperating with a movement popular among the masses would enhance Qatar’s own influence.

In Egypt during the “Arab Spring,” after then-President Hosni Mubarak was forced to step down in 2011, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi won the election and took power. Qatar supported the Morsi administration, while the Egyptian military backed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE carried out a coup, and in 2013 Morsi— was ousted. Similarly, in conflicts in Libya, Syria, and Somalia, among the intervening countries, positions diverged over whether to support government forces or opposition forces depending on politics and social circumstances. In other words, while armed conflicts were unfolding, Saudi Arabia and the UAE tended to back forces opposed to Qatar, producing confrontations that could be seen as “proxy wars.”

Outside traditional diplomacy, there is also a point of friction in public diplomacy. That is the existence of Qatar’s state-run media outlet, Al Jazeera (Al Jazeera), established in 1996. While Al Jazeera is cautious and restrained regarding Qatar’s own domestic politics and issues, unlike state broadcasters in other Arab countries that support closed and authoritarian regimes, it reports comprehensively and critically on global affairs, including the Middle East. It broadcasts in both Arabic and English to the world beyond the Middle East, and it has become an international broadcaster comparable to CNN and BBC. Through its reporting, it aims to raise the global profile of Qatar. This too is perceived as a threat by Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern and North African countries. Thus, many points of friction had accumulated between Qatar and its neighboring Arab states.

The Al Jazeera news channel (Photo: Wittylama / Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

The outbreak of the Qatar crisis

On June 5, 2017, a sudden crisis hit Qatar. Four neighboring countries—Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, and Bahrain—announced they were severing diplomatic relations with Qatar. They cut off land, sea, and air routes to Qatar and demanded the departure of Qatari diplomats from their countries. As reasons for the break, they cited Qatar’s friendly relations with Iran, which is hostile to Saudi Arabia, and its support for the Muslim Brotherhood. Then on June 22, Saudi Arabia and the other countries presented a specific list of 13 demands to Qatar. These demands were announced through then-88-year-old Kuwaiti Emir Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, a neutral mediator. The demands included shutting down Al Jazeera and all related outlets, downgrading diplomatic relations with Iran, and immediately closing the Turkish military base in Qatar.

In response, Qatari Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani took a hard line and rejected the demands. What began with four countries declaring a break in relations soon expanded as other Middle Eastern and African countries such as Yemen, Sudan, and Libya joined in. Meanwhile, Oman and Kuwait, members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), took a neutral stance. As one means of breaking ties, five countries—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Bahrain, and Yemen—halted all flights to Qatar and banned Qatari aircraft from flying over their airspace. The Qatar Stock Exchange saw an 8% drop, and the cutoff in trade with neighboring countries led to shortages of essential food imports. The crisis also affected oil prices, prompting OPEC to work to stabilize them. Although Qatar is the world’s largest supplier of natural gas, the rupture limited its export destinations.

A Qatar Airways plane (Photo: Clément Alloing / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

U.S. involvement

How did the United States engage with this Qatar crisis? For the U.S., Saudi Arabia is both a source of oil imports and a major destination for U.S. arms exports, while Qatar hosts the largest U.S. base in the region; both relationships are important. After the crisis broke out, then–Secretary of State Rex Tillerson emphasized a neutral position, saying the parties should talk to resolve the issue. At the same time, however, President Donald Trump adopted a more critical stance toward Qatar. He posted tweets supportive of Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and he also tweeted accusations that Qatar funded extremists. The divergence between Secretary Tillerson and President Trump suggested a bifurcation of U.S. diplomacy.

Why did President Trump take that stance? He had long engaged in business dealings related to Saudi Arabia. In 2015, before taking office, he even said, “The people of Saudi Arabia have been buying my real estate. They spend $40 million, $50 million. Am I supposed to dislike them?” In addition, influenced by Saudi Arabia and Israel, he is said to view Iran as his greatest enemy, making it difficult to side with Qatar, which maintains friendly relations with Iran.

Moreover, Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor, has a very close relationship with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. There were also reports that when a Kushner-owned property in New York was in financial trouble, he sought help from Qatar’s finance minister, Ali Sharif Al Emadi, but one month before the crisis began, the loan was denied. These Saudi and Qatari connections surrounding Kushner may have influenced President Trump’s thinking to some extent.

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson before a meeting with the Emir of Qatar (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikipedia [Public domain])

Who are the winners and losers of the Qatar crisis?

Nearly three years after the start of the crisis, how have Qatar and other neighboring countries fared? At the outset, Saudi Arabia and the UAE expected the break with Qatar to yield results quickly, because more than 60% of Qatar’s trade passes through Saudi and UAE ports, according to reports. In reality, however, contrary to those expectations, the confrontation has dragged on.

With the rupture with neighboring countries, goods from Qatar’s main suppliers, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, disappeared, and supermarkets in Qatar temporarily faced shortages. However, Qatar decided to cooperate with its previously friendly partners Iran, Turkey, and Oman to import supplies such as food. Economically, the Qatari government worked to attract foreign investment so businesses would not flee the country and used reserves to prevent prices from rising. In addition, it prioritized funding for the large-scale construction projects for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, and many global companies established branches in Qatar to avoid the impact of the rupture.

According to an IMF report, Qatar’s annual economic growth rate dipped from 2.1% in 2016, the year before the crisis, to 1.6% in 2017, but recovered to 2.2% in 2018. At the same time, growth in Saudi Arabia and the UAE fell to -0.7% and 0.7%, respectively, in 2017.

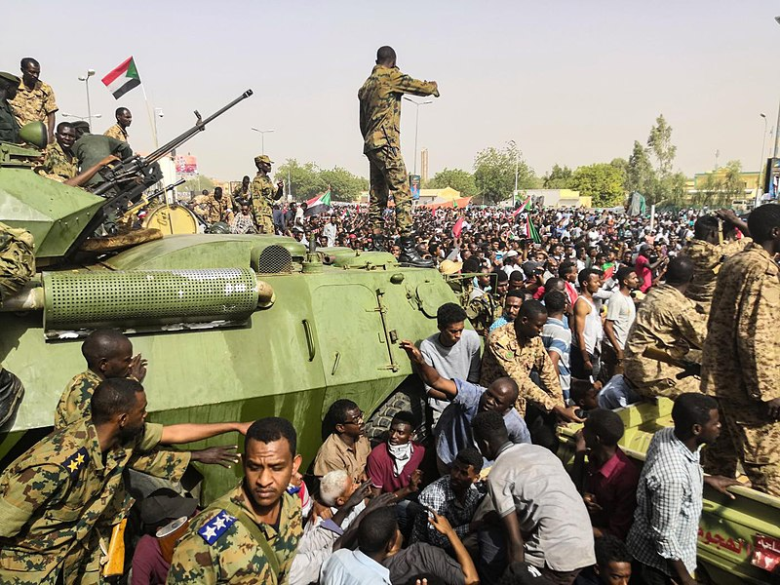

Furthermore, the impact of the Qatar crisis has not been limited to the main parties—Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. In various countries, political upheavals that can be seen as an extension of the “Arab Spring” have occurred, and Qatar and other Arab states have clashed amid that turbulence. In 2019, during the popular uprising and coup in Sudan, African and Western countries sided with the protesters, while Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE backed the government at the time and subsequently the military regime. In the same year in Libya, Turkey and Qatar, which supported the Government of National Accord (GNA), faced off against the UAE and Egypt, which supported the opposition, in a prolonged confrontation. In the Yemen conflict, Qatar and Saudi Arabia originally supported the same side, but after the crisis began, the two countries split in Yemen. In this way, the display of competing influence by different states in third countries may have been intensified by the Qatar crisis.

Scenes from the upheaval in Sudan (Photo: Agence France-Presse / Wikipedia)

On the other hand, there have also been developments that can be seen as an “easing” of the crisis. One example is Saudi Arabia’s announcement that it would participate in the 2022 World Cup to be held in Qatar. In September 2017, while the rupture continued, Qatar also promised to welcome fans coming from the four blockading countries—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain. Nasser Al Khater, CEO of the 2022 World Cup, said, “We hope relations will have improved by then.”

In addition, Saudi Arabia appears to have less ability to maintain a hard-line stance. It has struggled in the Yemen conflict and has faced criticism from other countries over the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. On top of falling oil prices since 2014, tensions with Russia from 2020 have pushed its economic situation further in the wrong direction. These factors have weakened Saudi Arabia, and it appears to be voicing even less criticism of Iran, with which it has long had deep-seated antagonism.

However, as noted at the beginning, ominous signs remain, such as the appearance of false information claiming a coup against Qatar’s Emir. Marc Owen Jones, who investigated this fabricated coup story, said, “This fabrication may have been carried out by Saudi Arabia to distract from its own crises of economic conditions and the spread of the coronavirus.” If so, despite developments that can be seen as an “easing” of the crisis—such as Saudi Arabia’s announcement that it would participate in the World Cup—the resolution of the Qatar crisis may still take time. We will continue to watch developments closely.

Writer: Naru Kanai

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

カタール独自の外交についてよく理解できました。その外交が機能した要因はなんでしょうか?政府の力が大きいのでしょうか?

コメントありがとうございます。カタールの外交が機能した理由は政府の力に加え、自然資源の豊かさという地理的な理由など、様々な要因が絡んでいるのではないかと、私は考えています。

中東地域の複雑な関係性について、分かりやすく解説されていたので、とても読みやすかったです!これからの動向にも注目していきたいですね

さすがなるねえさん、カタールとか結構他人事やと思ってたんですが、僕でもよく理解できてとても分かりやすかったです。もっと情勢に関して自分のアンテナをはる大切さを学びました。ところでカタールの危機ってあとどれぐらい続くと思いますか??

コメントありがとうございます。そう言っていただけて嬉しい限りです。カタール危機ですが、私自身もどのくらい続くかという点に関しては、周辺国の姿勢の変化が大きく影響するのではないか、と考えており予想するのは難しいです…今後の動向を見守っていけたらいいですね。

詳しくてわかりやすかったです!アメリカの関与の部分は特に興味深く読ませてもらいました!

カタール危機についてわかりやすくまとめられていて良い記事だと思いました。

カタール危機はなんとなく終結したものだと思っていましたが、まだ続いていることに驚きました。

経済制裁を受けて、大きく打撃を受ける国が

ある中で、国交を断絶されたカタールが経済維持するだけでなく経済成長できたことの決定的な理由は何でしょうか。

コメントありがとうございます。カタール危機勃発後も経済成長を遂げていたことを知り、私自身も驚きました。記事の中で述べた通り、友好国との関係構築・早急な国内ビジネスへの対応など、ピンチを力に変えることができたことが大きな要因ではないか、と考えています。

分かりにくい中東の話がとても読みやすく書かれていました!今後、カタールはさらに世界で大きな力を持つようになるのでしょうか?

コメントありがとうございます。中東地域の理解が深まったようでうれしいです。カタールは外交面では独自路線を貫き影響力を持つほか、天然資源も豊富であるという点で、ますます世界中が注目する大きな国の一つになっていくのではないか、と私は考えています。