From 2019/4/8 to 27, 500,000 teachers in Poland took part in a strike. Lasting 20 days, it was the longest and largest strike in Poland since 1993. As many as 15,000 schools and 7 out of 10 education workers joined the strike. There was also a petition with over 1,000,000 signatures calling for a national referendum on education.

Yet in 2012, in the international assessment PISA (Note 1), Polish students ranked around the top 10 compared with other countries. This means they outperformed wealthier countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden. By 2015, 1 in 2 Polish students had received tertiary-level education. In other words, Poland’s education system was among the best in the world. So what is happening in Poland?

Children studying at an elementary school (Photo: Alan Abernethy/United States Air Force) [public domain]

目次

Poland’s education system

In fact, after the Cold War, the growth of Poland’s education system was striking. In the 1990s, Poland had one of the lowest participation rates in upper secondary (high school) education among OECD countries. However, by 2012 the share of those aged 25~34 who had completed upper secondary education had grown to 94%, exceeding the OECD average of 83%. In 2015, Poland’s PISA scores were above the OECD average and at a similar level to countries such as Finland and Germany. In the 2012 PISA, Poland ranked 10th in reading and 9th in science, both within the top 10, and placed 14th in mathematics. The share of young people with tertiary education rose from 1 in 10 in 1989 to 1 in 2 in 2015, showing significant progress.

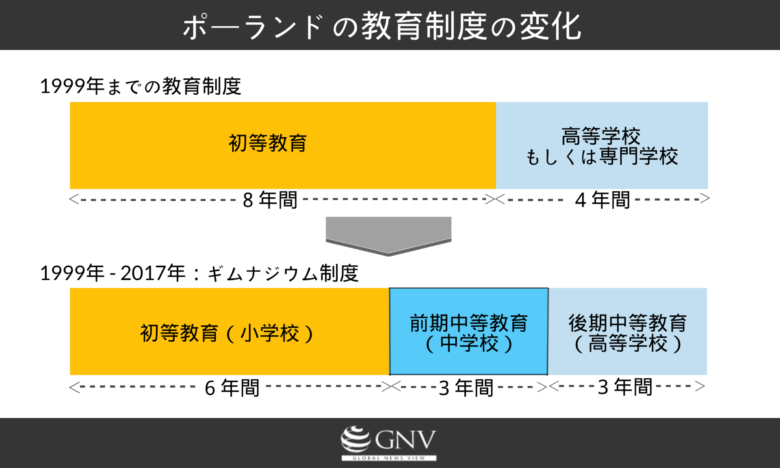

How, then, did Poland achieve such remarkable educational development? A major reason is that, after being freed from the Soviet sphere of influence at the end of the Cold War, Poland undertook a thorough reform of its education system. First, Poland introduced lower secondary schools called Gimnazjum (Gimnazjum). Until the Cold War era, the basic system was to receive primary education (elementary school) for 8 years and then choose either a general upper secondary school or a vocational school for 4 years. With the introduction of lower secondary education (middle school), after 6 years of primary school students then attended middle school and upper secondary school for 3 years each. This postponed by 1 year the point at which students had to choose between a general upper secondary school and a vocational school, allowing especially those who would go on to vocational school to receive an extra 1 year of education in middle school. Tracking into general or vocational pathways thus began at age 16, a notably later start than the OECD average of 14.

Before Gimnazjum was introduced, only the top 20% of students attended academically oriented upper secondary schools. With the introduction of Gimnazjum, many general upper secondary schools were established, and attending high school became the norm. As a result, 90% or more of students were able to receive upper secondary education.

In addition, in Poland students must take state-administered examinations when finishing primary and lower secondary school. Student performance is also monitored through large-scale international tests such as PISA, TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) (Note 2), and PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) (Note 3). Based on school-specific criteria that combine teacher assessments and exam results, students are decided for promotion or retention; the share of decisions based on these criteria is 98%, higher than the OECD average of 77%. Examinations clearly carry great weight in Poland. Moreover, because high-quality early childhood education is considered to significantly improve outcomes, Poland introduced policies to promote preschool. In 2014, Poland required all 5-year-olds to receive foreign-language instruction in preschool, and the share of children in early education rose to 82%, well above the OECD average of 61%.

Another hallmark was the high degree of autonomy for schools. The Ministry of Education granted schools substantial discretion over curricula and assessment methods, and Poland’s level of autonomy was above the OECD average. In addition, ideological components in curricula were removed to modernize education. Finally, Poland focused on improving teacher quality. Preschool and primary teachers are required to complete statutory practicum components and hold a degree, while lower- and upper-secondary teachers must hold a master’s degree. In these ways, Poland succeeded in raising educational standards.

Near-miraculous economic growth

Alongside these improvements in educational standards, Poland achieved remarkable economic growth. In 2015, Poland’s GDP per capita exceeded by more than 2 times its 1989 level, reaching 24,000 US dollars. The rate of GDP per capita growth was the largest among Eastern European countries. Exports increased more than 25-fold, reaching about 240 billion US dollars in 2015. Such growth made it possible to carry out education reforms, including building new schools and increasing the number of teachers.

Conversely, the elevation of educational standards also contributed to economic growth. Raising the nation’s educational level improved cognitive skills such as literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving, as well as abilities like teamwork and occupation-specific technical skills, thereby cultivating a higher-quality workforce. Reforms such as curriculum changes, modernization of national qualification frameworks, and closer links with employers strengthened the connections between the education system and the labor market. In this way, Poland achieved major gains both economically and educationally.

Education reforms by the Law and Justice party

Despite this steady progress, why did the outlook darken, culminating in a large-scale strike in 2019? One reason is that since 2015 Poland has been governed by the Law and Justice (PiS) party led by Jarosław Kaczyński. The government strengthened policies that directly transfer money to citizens, such as establishing a special child allowance, raising the minimum wage for employees, and lowering the pension eligibility age. However, as these policies were introduced, an excessive share of the budget went to cash transfers and the quality of public services gradually declined. Many hospitals were closed, medical services were scaled back, and doctors at operating hospitals also moved elsewhere, further worsening the situation.

The government also overhauled the education system. Its 2017 education reform was a major cause of the strike. The government abolished the Gimnazjum model under which students attended primary school for 6 years followed by 3 years each of lower and upper secondary school, and reverted to the Cold War–era system of 8 years of primary school followed by 4 years at an upper secondary or vocational school. As a result, about 6,500 middle school teachers lost their jobs. Low pay and the reforms themselves led many teachers to resign; unlicensed teachers filled the gaps, lowering educational standards. Consequently, many students have shifted to private education. The restructuring also entailed major changes to syllabi, especially for Polish history and literature. School autonomy was reduced as well. Observers note that this was aimed at producing more compliant schools and achieving more centralized control.

Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the Law and Justice party (Photo: Piotr Drabik/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

Furthermore, the reforms reduced the number of students attending general upper secondary schools, and reports suggest more students feel stress and pressure. According to PISA analyses, Polish students perceive academic competition at home to be intense, to a degree much higher than in other countries. Amid rising stress, in 12/2019, a music video by the rapper Mata titled “Patointeligencja (Patointeligencja)” stirred the country. The song, about the pressures faced by affluent students at elite schools, garnered over 5 million views in just a few days. It depicts how, behind the image of high-achieving youths from middle- and upper-class families, there is drug, alcohol, and tranquilizer use, and even suicide at times. “School phobia” has become a serious problem among students, suggesting a decline in Poland’s education system.

Background to the strike

Nor did the reforms stop at restructuring. Education Minister Anna Zalewska, arguing that too much of the national budget was being used for direct cash transfers, introduced further changes to save money. As a result, 200,000 teachers lost their housing allowance. She also eliminated the bonus paid upon completion of the first 2 years of service and extended the period required for promotion from 10 years to 15. These changes also formed part of the backdrop to the strike.

The number 1 reason for the strike was cuts to teachers’ pay. By 2018, one year after the reforms, the average monthly salary for Polish teachers was 560–770 euros, far below the national average of about 1,080 euros. These wages barely cover the rent for a small apartment. Before the strike began, the two unions—the Polish Teachers’ Union (ZNP) and the Trade Union Forum (FZZ)—demanded an approximately 30% raise for all teachers. The government rejected this, saying the national budget had no room for such a large increase. It then presented 2 compromise proposals, both of which the unions refused. With talks collapsing, the strike began.

A nationwide strike took place. (Photo: Cybularny/Wikimedia Commons) [CC0 1.0]

The strike took place in 2019/4, and in the parliamentary elections held 1 month later, voter turnout increased by 21.9% compared with the previous election in 2014. Up to 20% of voters—including education workers and parents of students—had participated in the strike. Dissatisfaction with the decline in education quality under Law and Justice likely also contributed to the higher turnout. There is concern that the current government is moving in an authoritarian direction, and it may be difficult to rebuild the education system. How will this struggle over education reshape Poland’s future? What lies ahead for a country once hailed for a near-miraculous rise in educational standards?

Note 1 PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment. It is an international survey of learning outcomes conducted every three years, assessing reading literacy, mathematical literacy, and scientific literacy among 15-year-olds in OECD member countries.

Note 2 Refers to the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study.

Note 3 Refers to the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study.

Writer: Ikumi Arata

Graphics: Yow Shuning

ちょうどスウェーデンの教育のことゼミで研究し始めたところで、めちゃめちゃ興味深い内容やなって思いました、、!!もっと自分の研究テーマについて知識深めようと思えた、素敵な記事でした!!!

ポーランドが著しい成長をとげていたこと、そして新政権に対してデモが起こっていることも知らなかったので興味深かったです。「法と正義」が選挙で勝利したのはどんな点で支持を集めていたのか気になりました。

ポーランドでは最近排外主義やナショナリズムを唱える政党が強くなっている話を聞いたので、教育もその影響を受けているのかなと思いました。

ギムナジウムはポーランドにとってとてもいい教育方針だったと思うのですが、どうして冷戦時代の教育方針に戻したのか気になりました。

卒業以来初めて拝読しました。

教育制度を切り口に国の経済や政治が読み解かれ、

あまりの興味深さにどんどん引き込まれました。

これからも楽しみにしています。

Hello !!

I came across a 151 great tool that I think you should take a look at.

This site is packed with a lot of useful information that you might find insightful.

It has everything you could possibly need, so be sure to give it a visit!

https://dehir.hu/eletmod/a-jatekosok-mentalis-egeszsegerol/2025/01/08/

And remember not to overlook, folks, which one at all times can in this particular piece locate answers to address the most tangled inquiries. We made an effort to present the complete information via the most most understandable manner.