On February 4, 2019, a law was passed in Poland that shook the European Union (EU). The law allows the government to fine or dismiss judges who criticize the government. Such government interference with the judiciary is said to signal a decline in the “rule of law” and the rise of “authoritarianism.” For the EU, which upholds the rule of law as one of its fundamental values, this law poses a threat.

“Our courts”: Demonstration against the new law in Poland (Photo: Grzegorz Żukowski/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The decline in the rule of law is not limited to Poland. Globally, as of 2018 the rule of law had declined for two consecutive years. What is the rule of law in the first place? Why does its decline matter? This article explains the concept of the rule of law and examines global trends and country-level realities.

目次

What is the rule of law

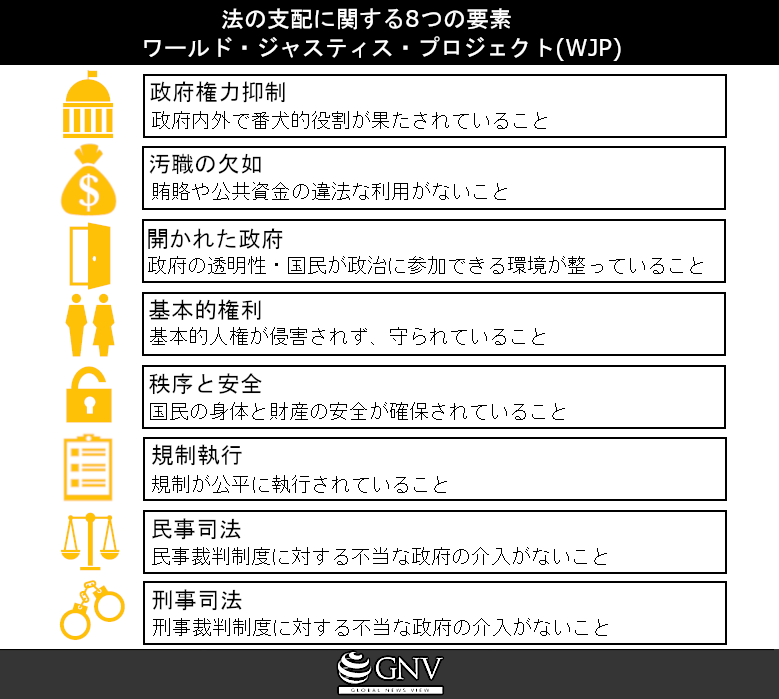

The rule of law is a principle that excludes arbitrary exercises of power by state institutions through law. In the sense that law limits power, it shares common ground with “rule by law.” However, under rule by law (where only the law’s proper enactment is required), the substantive fairness of laws is not questioned, whereas under the rule of law, all laws must conform to fundamental human rights. The scope of the rule of law is broad: it goes beyond merely requiring state institutions to obey statutes. The World Justice Project (WJP), a U.S. NGO that has surveyed countries’ rule-of-law realities and published annual reports since 2008, defines eight elements of the rule of law. The eight elements are described below.

The first is constraints on government powers: watchdog roles inside and outside government function, and government power is constrained by law. The second is the absence of corruption: bribery does not occur in state institutions and public funds are not misused. The third, open government, means that government information is disclosed to the public and people can actively participate in politics. The fourth is fundamental rights: the fundamental human rights set out in international law are not violated by domestic law and are protected.

Order and security is the fifth, indicating that people’s personal and property safety is guaranteed. This can be considered a prerequisite for the rule of law to function. The sixth is regulatory enforcement, meaning that legal and administrative regulations are enforced fairly and effectively. The seventh concerns civil justice: the civil justice system is free from improper government influence and corruption, and people can resolve civil disputes peacefully. The eighth is criminal justice, which similarly means the criminal justice system is free from improper government influence and corruption, and that investigations and judgments are carried out effectively. These are the elements of the rule of law. If each is met, a country can be said to have a high level of rule of law. Next, let’s look at global trends in each element.

Global overview

According to WJP’s 2019 report summarizing results for 2018, globally from 2017 to 2018 the elements that deteriorated were constraints on government powers, criminal justice, open government, and fundamental rights. The most countries saw declines in constraints on government powers—more than half of all countries surveyed—which can be said to tie to the rise of authoritarianism. Fundamental rights saw the largest decline in the past four years. These findings are echoed by other indicators. For example, Freedom House’s (Freedom House) research on civil liberties shows that global freedom has declined for 13 consecutive years. In addition, the African Governance Report (Note 1) finds that while the rule of law has improved overall in Africa, scores remain relatively low and many problems persist, such as the lack of mechanisms to prevent unconstitutional transfers of power.

Conversely, from 2017 to 2018, the elements that improved globally, in order of largest improvement, were regulatory enforcement, civil justice, absence of corruption, and order and security. Looking at other indices, Transparency International (Transparency International) reports that although corruption conditions improved from 2017 to 2018, the vast majority of countries still lack adequate measures. Across Africa, there were also improvements in the judiciary and protection of private property.

These are the global trends. So what do conditions look like in individual countries?

Rule of law: Top 5 and bottom 5

First, let’s look at the countries with the highest and lowest rule of law in WJP’s 2019 report. The top five, in order, were Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, and the Netherlands—largely Nordic countries. For the first-place Denmark, the country ranked first in four elements: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, regulatory enforcement, and civil justice. Norway, in second place, ranked first in open government, and Finland, in third place, ranked first in fundamental rights and criminal justice.

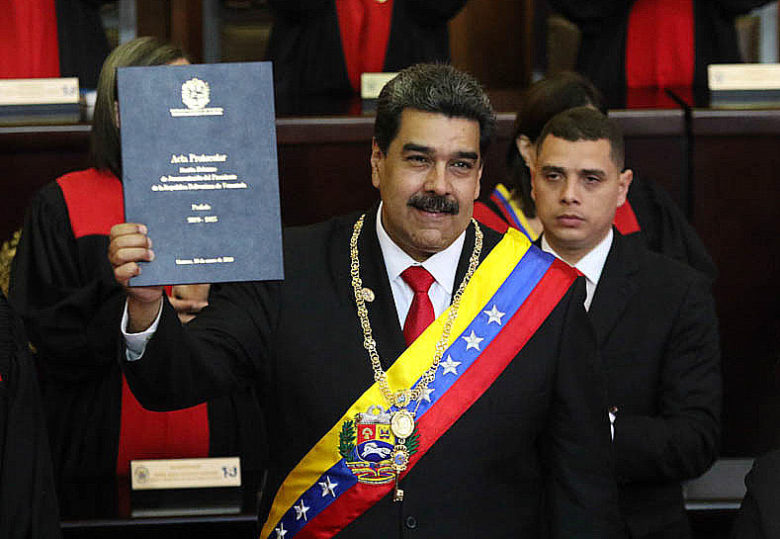

The countries with the lowest rule of law, from the bottom up, were Venezuela, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Afghanistan, and Mauritania. In last-place Venezuela, the Maduro government’s unlawful capture of the legislative and judicial branches was particularly conspicuous. For example, it made the Supreme Court subservient to the executive and dissolved parliament after the opposition won the 2015 legislative elections. The government also created a constituent assembly separate from the National Assembly and attempted to draft a new constitution. Cambodia shares Venezuela’s lack of constraints on government powers. In 2017, its Supreme Court dissolved the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). Prime Minister Hun Sen claims this decision was based on the “rule of law,” but it is considered merely an attempt to justify arbitrary exercises of power. The government has also pressured the press: in 2018, The Phnom Penh Post, one of the few remaining independent outlets, was sold to a Malaysian businessman with ties to the ruling party. Skillfully wielding diplomatic influence, the government persuaded Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia to detain and forcibly return CNRP members.

Ranked third-worst, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has extremely low rule of law amid conflict in the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu. Nationwide, former President Joseph Kabila’s authoritarian rule had long been a problem. In response, the new President Félix Tshisekedi has declared that he will prioritize tackling corruption and impunity and respect the human rights of all citizens. Next, Afghanistan ranks last in order and security among the elements. As GNV has previously reported, corruption is rampant in the government, judiciary, and police, and the Taliban has strengthened its influence. In Mauritania, ranked fifth-worst, slavery remains entrenched. Although a 2007 law criminalized slavery and anti-slavery organizations have been working on rescue efforts, it has not been eradicated. Human trafficking is rampant as well, yet the government has not taken sufficient measures.

Venezuela’s President Maduro (Photo: Presidencia El Salvador/Flickr [CC0 1.0])

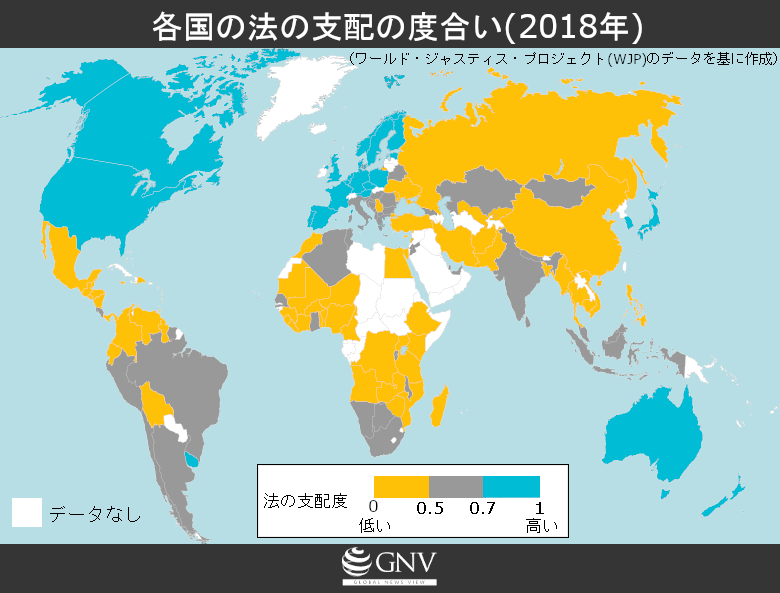

As the map shows, data collection is difficult in some places, and some countries are omitted from the WJP rankings; many of those likely have even lower levels of rule of law than the bottom five listed. Such countries broadly fall into two patterns. The first is countries in conflict, such as Syria, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. Because the rule of law entails constraining state power by law, protecting fundamental human rights, and maintaining order and safety, a state of conflict is essentially synonymous with the rule of law not functioning. The second pattern is authoritarian states, such as Saudi Arabia, North Korea, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, and Turkmenistan. Authoritarianism means power is concentrated in the head of state or regime and political freedoms are not guaranteed, enabling arbitrary exercises of power and preventing the rule of law from functioning.

Next, which countries improved or deteriorated from 2017 to 2018? Based on WJP’s 2019 report, we explain below what is happening on the ground.

Countries where the rule of law improved or declined

Countries that saw significant improvement include Zimbabwe, Guatemala, and Malaysia.

Zimbabwe’s President Mnangagwa (Photo: GovernmentZA/Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

In 2017, former President Robert Mugabe, who had ruled as a dictator for 37 years, was ousted, and Emmerson Mnangagwa assumed the presidency. President Mnangagwa has pledged to tackle human rights issues as part of reforms to rebuild Zimbabwe. After he took office, democratization progressed and improvements were seen, including in freedom of expression. However, parts of the electoral system remain repressive and freedoms are not fully guaranteed, leaving considerable room for improvement. In Guatemala, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) has investigated the past conflict (1960–1996) and crimes committed by military regimes. Active since 2007, CICIG has worked to support the eradication of entrenched criminal organizations and address current security issues. The homicide rate has reportedly declined, but challenges such as impunity remain. Another country with major improvement is Malaysia. As GNV previously reported, from 2009 to 2014, the “world’s worst corruption” occurred under former Prime Minister Najib Razak, but significant improvements have followed his arrest, and reforms by the new administration are underway.

On the other hand, some countries saw a marked deterioration in the rule of law, including Nicaragua, Iran, and Jordan. Nicaragua shows clear authoritarian tendencies: power has been concentrated in the executive, impunity is complete, and abuses against the opposition have been carried out. Anti-government protests in April and September 2018 were suppressed by police and armed pro-government groups, resulting in many deaths. The opposition has been thoroughly cracked down upon, and journalists covering the protests were detained.

A demonstration in Granada, Spain calling for the rule of law and democracy in Nicaragua (Photo: Julio Vannini/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The use of force to suppress protests was also seen in Iran. Many people have confronted a worsening economy, government corruption, and a lack of political and social freedoms. Since the first protests in December 2017, there have been mass arbitrary arrests and violent crackdowns. Around 4,900 people were arrested during protests in December 2017 and January 2018. As GNV previously reported, issues concerning women’s rights have also been conspicuous. In Jordan, calls for amendments arose because the definition of “hate speech” criminalized under the Cybercrime Law was vague, but the proposed revisions reportedly constituted backsliding: they defined “criticizing the government” as hate speech. In other words, the media would be suppressed and unable to play its role in constraining government power.

Going forward

We have looked at countries where the rule of law has improved or declined, but are there any countermeasures against the decline? This article has primarily drawn on WJP’s report to present conditions in various countries, and there are other organizations, like WJP, that research and report on the rule of law, corruption, and civil liberties as fundamental human rights.

“Equal under the law”: A painting of Lady Justice on a wall in South Africa (Photo: Ben Sutherland/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

As noted at the beginning, freedom has declined for 13 consecutive years since measurements began. Even social media—which should be a space for free expression and access to information—has been misused by authoritarians, and internet freedom in 2019 declined for the ninth consecutive year. In the face of this rise of authoritarianism, the reports introduced here shed light on the state and trends of the rule of law in each country and serve to draw attention to—and sound the alarm about—its decline. WJP’s 2020 report is scheduled to be released on March 11, 2020. We will be watching the results closely.

Note 1: African Governance Report: A report on governance in Africa by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, an organization that studies governance in African countries with the aim of improving citizens’ lives across the region.

Writer: Maika Kajigaya

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi, Yumi Ariyoshi

基本的人権の低下や法の支配の低下をどのように数値化しているのかについて気になりました。

とても分かりやすい記事でした!

法の支配と法治主義の違いについて、勉強になりました。権威主義の傾向が顕著である国では、基本的人権を尊重しない傾向にもあるので、基本的人権の適合を主張する法の支配の低下が見られます。冷戦の終焉に伴い、権威主義から民主主義に移行する傾向があったのですが、今逆戻りすることに残念だと思います。

グラフィックを見て、まだまだ法の支配の改善の余地が大きい国がほとんどであることに驚きました。

安倍首相は,よく「法の支配」という言葉を口にするが(官僚の原稿通りか,もしくは意味が分かっていないでつかっているか),この記事をよく読んで己が行っている行為が,日本における法の支配を危機に陥れているということを認識すべきであろう。しかし,彼は学問を一顧だにしない姿勢をモットーとしており,芦部信喜著の『憲法』という本すらご存じなく,立憲主義は権力をチェックするという意味ではなく国の理想を語るものだと国会で答弁しているので,この記事を読んでも考え方は変わらないでしょう。政府の原稿を書いている官僚はほとんど芦部の憲法を精読し理解し国家公務員試験に合格しているにもかかわらず・・・。