#PrayForAustralia (Prayer for Australia). This was a hashtag frequently seen on Twitter at the end of 2019, and tweets using it featured images of forests ablaze, firefighters continuing suppression efforts, and injured animals. From 2019 to 2020, Australia faced severe large-scale bushfires, and after 2020 began, coverage increased across the media. As of February, strenuous firefighting continues, but the damage keeps spreading.

Firefighters working tirelessly to contain the blaze in Cessnock, Australia (Photo: Quarrie Photography/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

2019 was a year when such large-scale fires raged not only in Australia but also in parts of Africa, the Americas, the Arctic, and Asia. Each fire has had major impacts locally and globally, but not all of them received the same level of media attention. This article examines the amount of coverage in Japan and the reasons behind it for major fires around the world.

目次

Fires occurring around the world

From 2019 into 2020, many of the world’s large wildfires have grown in scale, influenced in part by climate change. Forest fires also emit vast amounts of greenhouse gases, raising concerns that they in turn exacerbate climate change. Where are these large fires that have global implications occurring, and what damage are those regions suffering? Below we introduce fires in 6 regions, in descending order of area affected. (For area affected we refer to the reported burned area for each fire; because exact figures and definitions of “burned” vary, we avoid detailed enumeration.)

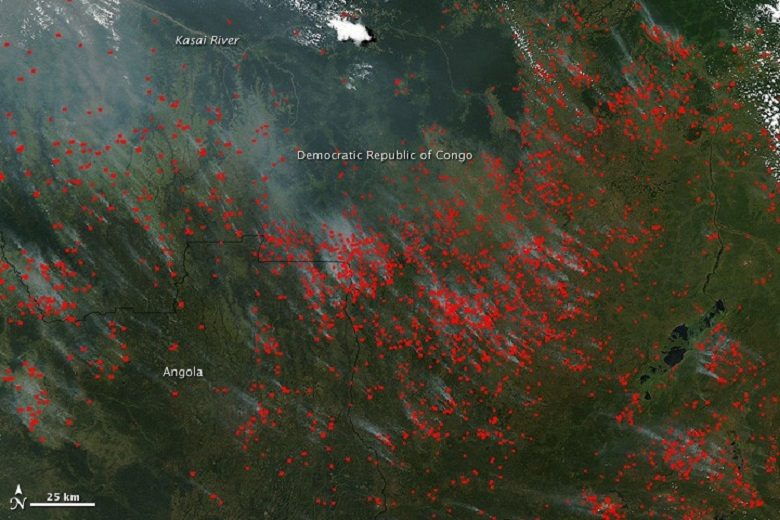

①Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Africa is the continent with the most fires, and even just the area south of the equator burns on a scale about 3 times the size of Japan’s land area. Among these, fires are particularly frequent in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo: in just the 48 hours from August 23 to 24, 2019, Angola saw 6,902 fires and the DRC 3,395. In terms of burned area during that 48-hour period, these ranked first and second in the world. The human and wildlife tolls are unknown, but Central Africa has suffered enormous damage. While often attributed to slash-and-burn farming, more forest than is necessary for securing food is being burned, making this a serious problem.

Fire locations in Central Africa (Photo: Jeff Schmaltz, NASA)

Fires occur every summer in Australia, but in 2019 extreme heat exceeding 40°C arrived earlier than usual, prompting earlier-than-normal outbreaks. Despite intense firefighting, the damage that began in September 2019 has continued to grow. As of 1/5/2020, 23 people and about 5 hundred million animals had died. Suspected causes include lightning strikes during the dry season, abnormal weather such as the Indian Ocean Dipole, and highly flammable eucalyptus trees.

Fires break out in this region every year, but in 2019 an abnormal situation arose in which they did not extinguish naturally. Brazil’s Amazon is one of the regions known as “the lungs of the Earth,” with about 20% of the planet’s oxygen produced by its forests. The burned area is roughly the size of one Kyushu region, and one cause is that the Brazilian government shifted policy toward actively promoting deforestation. As a result, extensive forest has been cleared, humidity in the Amazon has fallen, fires start more easily, and they are harder to put out.

Forests being felled in the Amazon (Photo: Matt Zimmerman/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

④The Arctic

As covered in a GNV article and in the Top 10 world news that flew under the radar in 2019, Arctic wildfires in Siberia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland and other sparsely populated regions caused little direct loss of life, but their scale was immense. The smoke from the Arctic fires covered about 7 million km², enough to blanket the entire EU (European Union). Causes include drying driven by climate change, heat lightning, and strong winds.

Also featured in GNV’s Top 10 world news that flew under the radar in 2019, Indonesia, located in Southeast Asia, experienced large fires driven by the Indian Ocean Dipole and land-clearing burns. The impact has been severe, compounded by fires burning on combustible peat soils. The carbon dioxide emissions from these forest fires in September and October 2019 were comparable to the country’s annual emissions, even though Indonesia is one of the world’s largest CO2 emitters, and the haze has affected neighboring countries.

On the U.S. West Coast, California also experiences numerous fires every year, and in 2019 a single fire burned 400 km². Red-flag emergency fire warnings were issued day after day in 2019, and because downed power lines can spark fires, utilities implemented planned blackouts affecting hundreds of thousands of households. These measures have not solved the underlying problem.

Which fires are being highlighted?

As we’ve seen, large fires broke out around the world in 2019, but which ones did Japanese media organizations focus on? We measured the Yomiuri Shimbun’s coverage during 2019 and, considering that these fires occur regularly, totaled coverage from 2010 onward. (※1)

The numbers first show that the Yomiuri Shimbun produced very little coverage in 2019 about fires in the six regions. There were 14 articles on Brazil, and coverage of the Australian fires increased mainly on social media and the internet after 2020 began; by 1/22, 2020, the total had also risen to 14. In contrast, Indonesia’s fires received 3 articles, California’s 2, and there were none on Central Africa or the Arctic.

To compare coverage of the six regions with another fire of a different nature and scale, consider the Paris Notre-Dame fire, the overseas fire most reported on in Japan in 2019. From April 15 to 16, 2019, the Notre-Dame Cathedral, a World Heritage site in Paris, France, went up in flames, and its central spire collapsed. This story drew intense attention in Japan as well, ranking 2nd in Yomiuri’s 2019 list of Top 10 Overseas News, comparable to the attention paid to the Shuri Castle fire in Japan.

Compared with the coverage above of the Notre-Dame fire, the scarcity of reporting on the six regional fires is striking. Although the Notre-Dame fire occurred in April, 79 articles were written in the nine months that followed. Compared with Brazil’s fires, that is 5.6 times more coverage. There were 210 articles about the Shuri Castle fire, which was a major topic in Japan; considering that the ratio of domestic to foreign coverage in the paper is about 10:1, coverage of Notre-Dame was substantial even relative to domestic news.

What determines fire coverage?

So what criteria determine the amount of coverage? When media report on disasters today, three main factors likely guide decisions: first, large numbers such as area affected or death toll; second, whether the disaster is unusual (novelty); and third, how much the disaster affects Japan. Let’s consider the six regional fires against these three points.

First, if area affected directly drove coverage, one would expect far more reporting on Central Africa. Yet there was no coverage of Central Africa from 2010 onward, there was some coverage of Australia and Brazil, and only one article on the Arctic since 2010. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s fires received more coverage than the Arctic’s despite the latter ranking ahead in area burned. California’s fires, although smaller in scale, have been reported relatively more often since 2010, indicating no clear correlation between coverage and area affected. Nor is there a clear correlation with death tolls, since tallies for Central Africa, Brazil, and Indonesia are not consolidated or widely reported. Considering human impacts, however, one might argue that Indonesia’s fires are reported because haze spreads across Southeast Asia and could worsen, whereas Arctic fires are less likely to directly affect people and thus receive less attention.

Kuala Lumpur blanketed in haze (Photo: Benjy8769/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Second, if novelty were key—coverage rising when a fire occurs for the first time or is larger than usual, and falling when it happens every year—then “newness” would be decisive. The very word “news” comes from “new,” so novelty should matter. Yet all of these fires have occurred for years, and while their scale increased in 2019, novelty alone does not appear to explain the differences in coverage among the six fires.

Third, if the more a disaster affects Japan the more coverage it receives, then large fires anywhere should matter to Japan insofar as they accelerate climate change globally. Directly, fires affect Japan when smoke reaches it; indirectly, when tourism and commercial ties with Japan are disrupted in affected regions. Fires in regions with fewer such links should receive less coverage, which aligns with the lack of reporting on the Arctic and Central Africa. However, Indonesia—geographically close and with the greatest potential to affect Japan directly—received far less coverage than the Amazon. In short, there is no strong correlation between fire coverage and impacts on Japan.

Factors that distance the media from overseas fires

As we have seen, the presumed factors that determine coverage do not fully explain the actual reporting, and there are contradictions. Here we add three “hidden” factors.

First is the influence of prominent overseas media. Noting that the areas deforested in Brazil in July and August 2019 were more than triple those of the previous year, Western media in late August 2019 simultaneously highlighted deforestation and forest fires, warning of their impact on the global environment. Yomiuri’s articles on Brazil’s fires were written from late August onward, after Western coverage had gathered momentum. It is fair to say Japanese media were influenced by Western outlets in taking up the Brazilian fires. Indeed, surveying English-language reporting on 2019’s forest fires shows Brazil most covered, followed by Australia and the United States. Comparing that with Japan’s coverage suggests Japanese media weigh how much major foreign outlets report on a topic when deciding whether to cover it.

Second are the number and placement of overseas bureaus and geographic priorities in the media. The farther a region is from a bureau, the more difficult and costly it is to reach, and it is hard to report from places with limited transport infrastructure. Even if reporters make it there, staying incurs further costs, and in regions where there is no base (rainforests, the Arctic, etc.), time on the ground is limited, making it hard to produce in-depth articles. The Yomiuri Shimbun’s bureaus include Sydney and Los Angeles, both with good infrastructure, making Australia and California more accessible. There is also a base in Rio de Janeiro, but none in Central Africa or the Arctic, which are harder to access. Bureau placement reflects where news organizations focus their attention; Yomiuri’s international reporting tends to be concentrated on Asia and Europe and less on Africa. Thus, the Arctic and African fires may receive little coverage.

Third is the possibility that Japan contributes to the fires. In Indonesia, many fire-affected areas overlap with regions where pulpwood logging is conducted. This is partly because land is burned to make way for plantations. Japan imports large quantities of timber from Indonesia, and one of the eight companies logging pulpwood in the fire-affected regions is an affiliate of Japan’s Marubeni. In other words, Japanese companies are said to be among the factors behind Indonesia’s forest fires. Japanese media tend to avoid reporting when Japan’s government or companies are implicated in global problems. Therefore, even though Indonesia is geographically close and closely connected to Japan, Brazil—farther away and less connected—ends up receiving more coverage.

The far bank burning in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: CIFOR/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In 2019, areas around Japan saw fires over expanses far exceeding the country’s land area, yet the amount of coverage did not match the scale. The drivers of reporting are complex, but the result may be that the reality of global fires is not being fully conveyed. Unlike tsunamis after earthquakes abroad, overseas forest fires rarely cause direct damage in Japan. However, as forests burn, carbon dioxide is emitted and oxygen-producing trees are lost, and in environmental terms the consequences could ultimately affect Japan. Recognizing this, we should listen for the sound of forests burning.

※1 Aggregated Yomiuri Shimbun coverage in 2019 and from 2010–2019 across national and regional editions

Writer: Yoshinao Araki

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

0 Comments