On 2020/1/11, state media reported that Sultan Qaboos bin Said of Oman in the Middle East had died on the 10th at the age of 72. Although it had previously been reported that his chronic colon cancer had worsened and he was terminally ill, news of his death spread worldwide because he was a key figure in international relations, especially in the Middle East. While human rights abuses under his dictatorship had been a concern, he was also known as a ruler who developed the country and as a capable leader who orchestrated a diplomatic strategy so effective he was called “a star for peace in the Middle East.” This article explains the realities of authoritarianism, Oman’s diplomatic strategy, and the succession issue, along with the country’s historical background.

In 2010, the late Sultan Qaboos shakes hands with former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates (Photo: U. S. Department of Defense [Public Domain])

目次

Overview of Oman

Oman is a country of about 5 million people on the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, facing the Indian Ocean. Its population is concentrated along the coastline centered on the northern capital, Muscat. Nearby are the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, and across from its exclave on the Strait of Hormuz lies Iran. About 1/3 of the world’s oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz every day, making it geopolitically crucial. As noted at the outset, Oman is an absolute authoritarian state where dictatorship has continued for many years. The country’s formation has a history of change. Omani merchants prospered in trade from the Middle East to East Africa from ancient times. After occupation by Portugal in the early 16th century and later regaining control and flourishing, the advent of steamships gradually weakened Omani merchants who mainly used sailing vessels, and by the late 19th century it had been colonized by Britain. Even as it experienced a history of the country being divided by the British into inland Oman and coastal Muscat, in 1963 it became independent through a revolution led by the late sultan’s father, Qaboos bin Taimur, shaping today’s Oman. In this way, Oman has a history in which invasions and revolutions have been repeated.

From a religious perspective, Oman offers interesting insights. Like other Arab and Middle Eastern countries, most people are Muslims, but notably, many citizens including the sultan adhere to the Ibadi branch of Islam. This sect is known for emphasizing conservatism and tolerance, and about 3 out of 4 of the world’s Ibadi followers are said to be Omani nationals. As a result, Ibadi religious values are rooted in the daily lives of Omanis.

Let us also look at the economy. As in other Middle Eastern countries, the majority of Oman’s national income depends on natural resources such as oil and natural gas, accounting for 48% of GDP and 78% of government revenue, respectively. After oil was discovered in the interior in 1964, Oman focused on these natural resources—especially oil—and rapidly developed its economy through exports. In recent years, however, there have been moves to break away from dependence on natural resources. Alarmed by the vulnerability of an economy that can cease to function due to falling oil prices, Oman has drawn up plans to offset losses from moving away from oil by promoting renewable energy using solar and wind power and by developing tourism. Including such reforms to the economic structure, it has also launched “Oman Vision 2040,” aiming for further development by 2040, demonstrating a future-oriented outlook at the national level.

View of Muscat, the capital (Photo: Sam Gao / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Oman under Sultan Qaboos

The late Sultan Qaboos bin Said wielded enormous influence through decades of dictatorship. In 1970, with support from British forces, he seized the throne from his father in a bloodless coup. He put down the rebellion by forces in the southern region of Dhofar that had continued since the 1960s with the help of Britain and Iran. Thereafter, he not only served as sultan, but also as prime minister, defense minister, and foreign minister, and simultaneously headed the central bank, concentrating power entirely in himself and reigning as the country’s leader for nearly 50 years. Exercising his leadership, he led the country’s modernization—which his father had resisted—joining the United Nations in 1971, expanding oil exports to drive economic development, and raising literacy rates and life expectancy, among other modernizing achievements. Combined with the length of his rule, his concentrated power gave Qaboos enormous influence at home and abroad, making it very difficult to gauge how his death will affect the Middle East region going forward.

So far, we have described his domestic achievements. While dictatorship can allow for strong leadership and swift political decisions, it often curtails citizens’ freedoms. Oman is no exception, and those seeking freedom are suppressed. For example, there have been actual cases of arrests of human rights activists and writers depicting state corruption. In addition, there is a severe lack of press freedom, such as restrictions on internet access, closure of online newspapers, and censorship of publications, as well as restrictions on assembly and association—conditions far from “free.” Reflecting this, the 2019 report by the U.S. NGO Freedom House rated Oman at 23 points out of 100, indicating that very little freedom is recognized. In 2018/1, penalties for insulting the sultan were toughened, and these restrictions have grown stronger, raising serious concerns that repression of citizens will intensify further in the future.

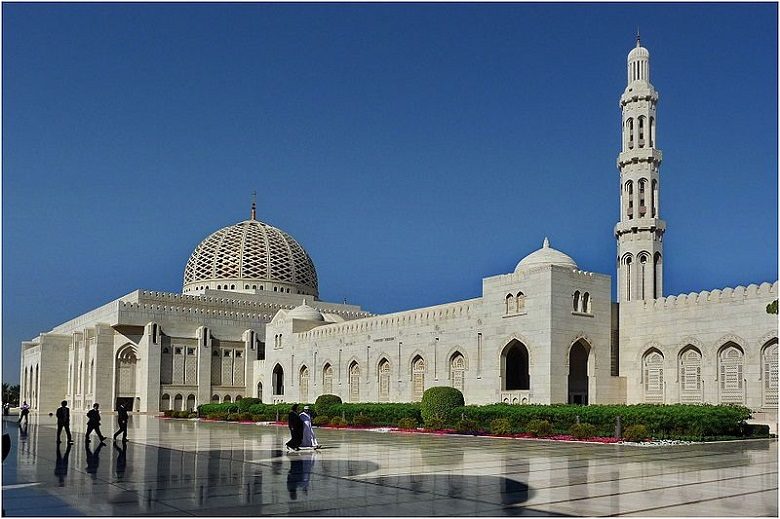

The Royal Mosque in Muscat, the capital (Photo: patano / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Oman’s foreign policy

Having outlined the country’s background and Sultan Qaboos’s domestic governance, we now turn to Oman’s foreign policy. Oman has refrained from military intervention in conflicts and has often played the role of mediator—maintaining good relations with opposing sides while brokering between them. Its accomplishments are such that it has been described as the “Switzerland of the Middle East” and “a star of hope for peace in the region.” Let us look at Oman’s actual efforts.

The first instance where Oman’s independent actions drew attention was the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). In 1981, under the banner of safeguarding security in the Persian Gulf, Oman established the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) together with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Within the GCC were members such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait that fully backed Iraq against Iran, yet Oman acted while maintaining good relations with Iran. It showed flexibility—expressing support for the United States, which backed Iraq, while helping secure the return of Iranian soldiers captured by the U.S.—and contributed greatly to easing heightened tensions. During the Gulf War (1990–1991) sparked by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, Oman, together with other GCC members, actively supported the operation to liberate Kuwait; however, it opposed the 1998 U.S.- and U.K.-led military strikes on Iraq, demonstrating an independent diplomatic strategy. In an environment where antagonisms among many states were laid bare, Oman managed to act without making enemies and has earned the trust of many countries.

Scene from a 2016 meeting of GCC member states (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

In other regional clashes as well, Oman has built appropriate distance with each country through its unique diplomacy. It is said to be the only Gulf state that maintained diplomatic relations with Syria’s Bashar al-Assad regime after the “Arab Spring” democratization wave in and after 2010 in the Middle East and North Africa. In the Yemen conflict, it did not join the Saudi-led Arab coalition forces, keeping a certain distance from Saudi Arabia—which seeks to exert influence across the Middle East—and monitoring the situation from a broader perspective. Moreover, Oman reportedly accepted thousands of wounded Yemenis in its hospitals and provided free treatment. Regarding Qatar, which was cut off by most Middle Eastern countries in 2017/6, Oman instead strengthened trade ties, increasing exports of Omani products to Qatar and boosting bilateral trade by 2,000%, showing that its diplomatic strategy has had positive economic effects as well. In this way, Oman has served for decades as a mediator in the unstable Middle East and has enhanced its reputation.

Just as it keeps its distance from Saudi Arabia, Oman also maintains neutrality toward the United States. It concluded defense agreements with the U.S. in 1980, 1990, and 2000. After the 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S., Oman at times showed willingness to cooperate, yet it did not allow its military facilities to be used for the bombing of Afghanistan. Even while receiving financial support from the U.S. for security, Oman has not fully endorsed Washington’s stance toward Iran. Not being dependent on the U.S. may be the secret to its diplomatic success.

Indeed, Oman has played a very important role in U.S.–Iran relations. In 2013, Oman arranged a forum for the two countries to discuss nuclear issues and contributed significantly to the conclusion of the nuclear agreement between Iran and Western countries in 2015/7. However, when U.S. President Donald Trump announced in 2018/5 that the United States would withdraw from the nuclear deal with Iran, Oman issued a statement that “confrontation benefits none of the parties.” Coupled with the worsening of Qaboos’s health, Oman, as mediator, may have struggled to deploy a fully effective diplomatic strategy toward a more anti-Iran U.S., finding itself in a difficult position.

Group photo of ministers before the 2014 Iran nuclear talks (from left: Iran, EU, Oman, U.S.) (Photo: U.S. Department of State / Flickr [Public Domain])

The beneficiaries of Oman’s mediating diplomacy are not limited to Middle Eastern countries and the United States. In late 2007/3, when British marines were detained by Iran in the Persian Gulf waters and tensions rose, Oman played an important role in arranging their release. It also played a central role in negotiations that secured the return of three Americans detained in the summer of 2009 on espionage charges. In 2015, a French citizen; in 2016, two Americans; and in 2017, an Australian and an Indian Catholic priest were released in Yemen with Oman’s help—illustrating why many countries around the world look to Oman as a lifeline in Middle Eastern conflicts.

Future developments

Hours after the state broadcaster announced the death, it was reported that Haitham bin Tariq—a cousin of the late sultan, minister of culture, and chair of Oman Vision 2040—was appointed as the new sultan. Qaboos had no children or siblings and had not publicly named a successor. However, it is said that during his lifetime, as a will, he left a sealed envelope containing the name of his chosen heir, and Haitham was swiftly appointed in accordance with that will.

Although the new sultan has declared that he will “continue to play a positive role to calm many conflicts, as we pursue regional stability,” it is unclear how much he can maintain the domestic and international image of neutrality and mediation that the late sultan built. Conversely, if the new sultan continues everything as before, human rights issues may also remain unaddressed. Close attention will be paid to the policies the newly installed sultan puts forward. His leadership—both in foreign and domestic affairs—will be closely watched.

Writer: Taku Okada

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

オマーンについて長期政権で独裁という印象が強かったのですが、

外交面で柔軟な立ち回りをしているとは知りませんでした。

中東にはやはり紛争などのステレオタイプなイメージがありますが、

オマーンにはぜひそれを壊して平和の星としての役割を果たしてほしいと思います。

国内の人権問題と外交関係での友好関係の構築に試みという2つの側面があることが面白いなと思いました。新しい国王に期待ですね。

オマーンは外交政策についてほとんど知らなかったので、今まで抱いていたイメージとは大きく異なり驚きました。

新国王が統治するオマーンが興味深いです。