In 2019, worsening economic conditions and hardship led to large-scale anti-government protests across the world. In Chile, demonstrations that began in the capital, Santiago, spread to other cities, and to date, more than 20 people have died. In Lebanon, citizen-led protests expanded and the situation escalated to the point that Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced his intention to resign. Elsewhere— Iraq, Iran, Ecuador, Colombia, Haiti, and Indonesia—looking around the world, one can see that mass protests with similar backgrounds occurred in many places.

These protests are said to have been sparked by austerity measures such as price hikes on necessities and tax increases, built on a foundation of accumulated public frustration in economically unstable countries. Yet while many people are unable to endure such harsh economic conditions, a slight shift in perspective reveals that there are also world-famous billionaires. What disparities exist between these groups, and what has produced them? This article explores those questions.

Anti-government protests in Chile (Photo: Carlos Figueroa / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

Overview of inequality

First, what kinds of disparities exist in the world we live in today? According to the 2019 edition of Oxfam International’s annual January report on inequality, the combined wealth of roughly 3.8 billion people—the poorer half of the world’s population—is equal to the combined wealth of just 26 of the richest individuals. Moreover, in 2018, while the wealth of those 3.8 billion decreased by 11%, billionaires with assets of over US$1 billion continued to increase their wealth at a pace of US$2.5 billion per day. Furthermore, according to the annual report by Swiss financial firm Credit Suisse, 45% of the world’s wealth is controlled by just 1% of people.

Inequality also exists within countries. Since the 1980s, in many nations the share of national income going to the wealthiest 1% has continued to increase. Even in seemingly affluent high-income countries, wealth is being concentrated at the top, and the gap is severe. For example, in the United Kingdom, the richest 10% hold 44% of national wealth, and in the United States, the household income of the top 1% is about 25 times that of the other 99%. Such disparities have persisted for many years. Comparing the top fifth and bottom fifth of countries by wealth, the income ratio of their residents expanded from 30 to 1 in 1960 to 74 to 1 in 1997—more than doubled.

In response to poverty created by such inequality, the UN summit in 2000 established eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The first goal was “Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger.” The associated target—“halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day”—had some problems in how it was measured, but it was achieved by the 2015 deadline. However, this achievement was driven by the rapid economic growth of populous countries such as China and India; many other low-income countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, did not meet the target. While the poorest countries have also made gradual economic progress, the pace has been slow. High-income countries have grown much faster, and the gap continues to widen.

Following the MDGs, the 2015 UN Sustainable Development Summit set 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the first of which is “End poverty in all its forms everywhere.” Related targets call for “ending extreme poverty everywhere” and “reducing at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions,” yet concrete measures to achieve these have still not been presented. The SDGs were set with a pledge to “leave no one behind,” but without major change, by 2030 more than 400 million people in Africa are expected to remain in extreme poverty.

The background of inequality

So what is widening economic inequality in recent years? Domestically, one factor is the legacy of colonialism. Most low-income countries were formerly colonies. For the convenience of the colonial powers, systems were established that concentrated labor on a single natural resource or crop, giving rise to monoculture economies reliant on its export. After independence, there was little economic capacity to significantly reform these systems, and they largely persist today. Monoculture economies are easily hit hard by international price drops or poor harvests, preventing domestic economic stability. This also delayed industrialization, so these countries still mainly export raw materials for industrial products and cannot engage in value-added trade such as importing raw materials, processing them, and exporting finished goods. Domestic political issues such as corruption and embezzlement are also cited.

What about the international background? From several angles, we can see a structure in which the haves exploit the have-nots. First, consider international trade. There is the problem of illicit financial outflows, in which foreign companies operating in low-income countries use tax havens to obscure financial flows during trade, avoiding tariffs and corporate taxes. Fully half of global trade passes through tax havens. In addition, when companies or plantations in low-income countries are sellers, buyers from advanced economies often use their bargaining power to set prices, and raw materials or products are bought at unfairly low prices; unfair trade is rampant. This leads to foreign corporations monopolizing profits. Through this structure—where wealth flows from low-income countries to high-income countries—inequality is maintained and reinforced.

Women working at a quarry (Photo: Nick Fox/Shutterstock)

Furthermore, climate change—widely warned about around the world—also appears to be a factor. Droughts, sea-level rise, and extreme weather are among the many life-threatening problems caused by climate change, and industrial countries’ greenhouse gas emissions are considered the cause. The ability to respond to these problems, however, ultimately depends on economic power. People currently living in poverty bear little responsibility for climate change, yet compared to the wealthy, it is clearly more difficult for them to take adaptive measures such as purchasing costlier food, installing climate control in homes, or building seawalls, pushing them into even more precarious situations. This is the emerging inequality of modern society known as climate apartheid. It is predicted that by 2030, about 120 million people will be pushed into poverty as a result.

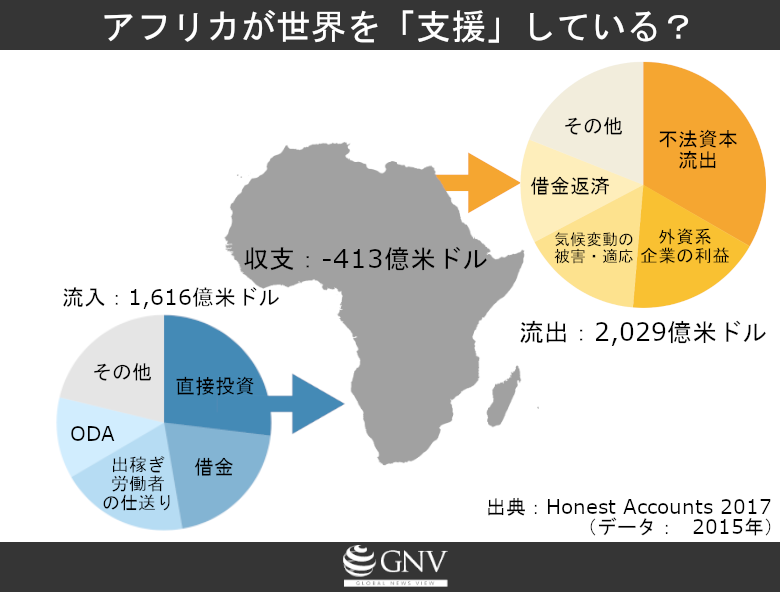

To be sure, there are also capital inflows in the form of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). But outflows are overwhelmingly larger. For example, according to data jointly released in 2017 by NGOs around the world, including Global Justice in the United States and Health Poverty Action in the United Kingdom, in 2015 Africa received about US$162 billion in inflows, while roughly US$200 billion flowed out due to illicit capital flight, foreign corporate profits, and the damage from—and responses to—climate change. African countries do receive economic assistance from international organizations and high-income countries, but remarkably, the balance is deeply in the red. In this way, international factors are intricately intertwined and appear to contribute to inequality.

Going forward

Many approaches have already been proposed to resolve global inequality. The problems associated with tax havens have often been a focus of international discussions, and at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD3) in 2015, institutional reforms at the level of international organizations were on the agenda. However, due to strong opposition from high-income countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, this did not materialize. Other approaches include tax policy. At the domestic level, higher income tax rates can help redistribute wealth and reduce inequality. At the international level, there is the idea of a Tobin tax—taxing foreign exchange transactions to curb speculative profits and using the revenue to support low-income countries—and also the “air ticket solidarity levy,” imposed on international flights and adopted by several countries including France. However, each faces significant hurdles: domestic income tax increases face pushback from economically powerful elites, and the Tobin tax faces opposition from high-income countries. Addressing the inability of low-income countries to add value in international trade could involve efforts to promote industrialization. Yet given how far behind they are, it is hard to imagine competing with established manufacturing powers. Moreover, reconciling industrialization with climate change measures is a major challenge.

There are also initiatives by citizens and companies. For example, fair trade has become more widely known in recent years. As noted, many producers are disadvantaged in the global trade structure where unfair trade is rampant. Fair trade seeks to promote more equitable and just transactions in such circumstances, with systems like minimum price guarantees, long-term contracts, and premiums for producers. However, this is merely trade at a fair price. It is certainly better than unfair trade, but it cannot be said to dramatically improve the situation. Moreover, under existing fair trade certification schemes, the minimum prices and premiums guaranteed to producers are far too low, and the current situation does not provide sufficient income.

Cargo ship (Photo: Lukasz Z/Shutterstock)

Economic inequality and disparities are extraordinarily serious and deep-rooted problems that have been created and maintained by the world’s political and economic structures. As the current situation shows, rather than improving, inequality continues to grow. However, some people have begun to reject these as unacceptable, proposing ideas and taking action. Oxfam International’s report, which has revealed striking data about the gap between the economically wealthy and the rest, is released every January. The 2019 edition found that the wealth of 3.8 billion people in the bottom half equals that of just 26 at the top. The number of people at the top whose combined wealth exceeds that of the 3.8 billion has been shrinking each year—what will the 2020 edition show? Will inequality have widened further, reducing that number even more?

Writer: Suzu Asai

Graphics: Yow Shuning, Saki Takeuchi

持つ者が持たざる者を搾取する という言葉が印象的でした。1月のオックスファムの報告書、必見ですね。

格差が広がる一要因としてあげられていたモノカルチャーは、根付いてしまったからにはなかなか抜け出すのが難しいように思われます。現状の深刻さだけではなく、「先進国」「消費国」に強要されてそうならざるを得なかった歴史を、消費する側としては当事者意識を持って受け止める必要があると感じます。

「格差」という言葉はよく耳にしますし、世界的な問題になっていることは理解しているつもりでした。

ただ、思っていたよりその問題が大きく、いわゆる先進国も関わっていることは実感していなかったので、おどろきました。

高所得国と低所得国のGDPに関するグラフの乖離に衝撃を受けました。

世界的にみると貧困状況にいる人数は減っているが、アフリカに関しては不正なお金の動きが多く全く改善されず今後も続くことに衝撃をうけました。貧困の目標人数や割合にとらわれずに、本質的に貧困の解決に取り組んでいく必要性を感じました。

「アフリカが世界を支援している」ということがかなり衝撃的でした。

世界に一つだけの花