Mongolia is known as the country whose capital, Ulaanbaatar, is the coldest in the world. In May 2019, in this severely cold country, the government announced a ban on the use of coal. Even today, many households in Mongolia use coal. Nevertheless, the driving force behind taking such a bold step is the severe air pollution. Its level rivals—or even exceeds—that of cities like New Delhi, Dhaka, Kabul, and Beijing. A report compiled in 2018 by the National Center for Public Health of Mongolia and UNICEF issued the following warning: if the air pollution problem in Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, is not rapidly resolved within the next few years, by 2025 “the costs of treating children who become ill due to air pollution will increase by 33%.” As this wording indicates, the air in Ulaanbaatar has reached a crisis point that harms people’s health. What exactly is happening in Mongolia?

Ulaanbaatar, shrouded in smog, is surrounded by mountains on all sides (Photo: Einar Fredriksen/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

The capital, Ulaanbaatar

In fact, severe air pollution in Mongolia is confined to the capital, Ulaanbaatar. From October to May, the winter period, the skies over Ulaanbaatar are covered with a dim, foul-smelling smoke. Even when you venture out, only a few meters ahead is hazy, and your mouth turns pitch-black with soot even if you wear a mask. This smoke comes mainly from raw coal burned in households. There are reasons why this phenomenon occurs only in Ulaanbaatar and nowhere else.

The first reason is the cold. Mongolia’s air pollution is limited to the winter, and during polluted winters the mortality rate is 350% higher than in summer. There are many sources of air pollution—such as emissions from thermal power plants, factories, and waste incineration—but the biggest factor is coal stoves fired inside gers and other buildings. The smoke they emit, along with harmful substances, covers the entirety of Ulaanbaatar. A ger is Mongolia’s traditional portable dwelling. Suited to the highly mobile lives of nomads, it can be assembled in about 2 hours, and when the centrally placed coal stove is running, it can withstand temperatures as low as minus 40℃. This traditional coal stove serves not only as a heat source but also as an oven for cooking. For that reason, the sky over Ulaanbaatar is especially dark on winter mornings and evenings. Throughout the winter, the city consumes about 1.2 million tons of raw coal—an astonishing amount.

Life inside a ger (Photo: Al Jazeera English/ Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The second reason is population concentration. As of 2018, Mongolia has about 3.2 million people, and about 45% of them are concentrated in the capital. The background to such a concentration in one place is poverty in rural areas. In Mongolia, where much of the population traditionally consists of nomadic peoples, many in rural areas still practice a nomadic lifestyle, moving repeatedly while herding livestock such as sheep and goats. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to earn a stable income this way. One reason is “dzud.” Dzud refers to severe winter cold and heavy snow that follow a dry summer drought. When a dzud occurs due to climate change, livestock that did not eat sufficient pasture in summer cannot survive the winter and freeze to death in large numbers. For nomads, losing livestock means losing their wealth. As a result, not only animals’ lives but also human lives and livelihoods are threatened.

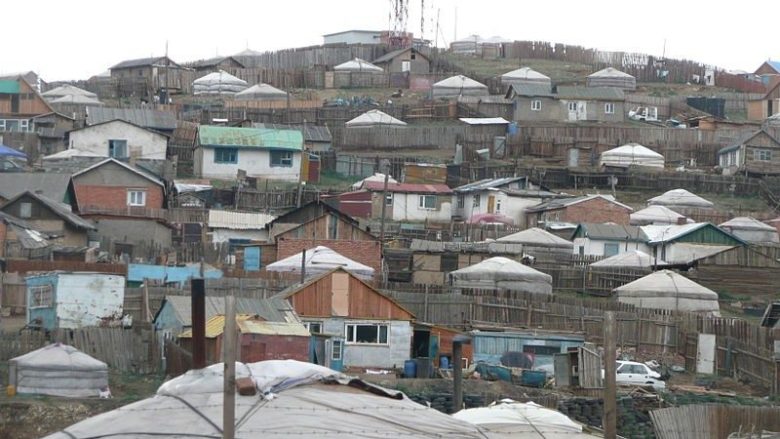

In recent years, Mongolia has seen hotter summers and colder winters, and the frequency of dzud has been increasing. According to the Mongolian Red Cross Society, what used to occur once every 12 years has, over the past 30 years, been occurring once every 3.8 years. Consequently, in search of a better life, nomadic families—often prompted by their children’s schooling or employment—continue to move to the capital, Ulaanbaatar, which generates more than half of the country’s GDP. Centered mainly in the northern part of the city, “ger districts” have spread as residential areas for these migrants, and now more than half of all households in the city live in ger districts. The smoke that accounts for 80% of the causes of air pollution is said to come mainly from these areas.

A ger residential district (Photo: Brücke-Osteuropa/ Wikimedia Commons)

Furthermore, the area’s distinctive topography contributes to the worsening situation. Ulaanbaatar lies in a low basin, surrounded by mountains on all sides. As a result, in winter the smoke and dust are capped by cold air and do not escape, creating a phenomenon called a “temperature inversion.” This causes the smog to remain trapped in place with nowhere to go.

Young victims

PM2.5 (fine particulate matter) is believed to be involved in the various health problems rampant in Ulaanbaatar. PM2.5 refers to particles with a diameter of 2.5μm or less (about one-30th the thickness of a human hair). Because they are so small, they can penetrate deep into the lungs and affect not only the respiratory system but also the circulatory system. At 5 a.m. on January 30, 2018, Ulaanbaatar recorded an astonishing 3,320μg/㎥ of PM2.5, which is 133 times the WHO (World Health Organization) guideline value.

By breathing air, eating food, and drinking water contaminated with such harmful substances, people are affected by air pollution both inside and outside their bodies. In 2016, it is estimated that 1,800 people died from illnesses caused by household air pollution and 1,500 people died from illnesses attributed to outdoor air pollution. Among those most severely affected are young children. Pneumonia is abnormally prevalent among children living in Ulaanbaatar. Compared to the previous year, 2018 saw a 40% increase in child deaths and injuries due to pneumonia, and the number of pediatric outpatient visits for pneumonia surged by 76.8%. Pneumonia is now the 2nd leading cause of death among children under 5, and there are reports that children living in the center of the capital have lung function that is 40% lower than that of children in rural areas.

Many children visit hospitals in Ulaanbaatar (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense Current Photos’s photostream/Flickr)

There are reasons why the impact is especially great on children rather than adults. First, their breathing rate is twice as fast as adults’. This means children exchange air with the environment more often and take in pollutants more frequently. Second, they are closer to the contaminated ground. Because children are small, they are nearer to the ground where some pollutants tend to accumulate, increasing the risk of inhaling them. In addition, their major organs are still developing, making them more susceptible to damage. However, children are not the only ones who suffer serious health effects from continuous exposure to polluted air; it also affects pregnant women carrying new life, increasing the risks of stillbirth, preterm birth, low birth weight, and congenital disabilities.

To keep young children away from such a dangerous city, some families have begun sending only the youngest children to live with grandparents in the countryside. Because parents remain in the capital to earn a living, many families are reluctantly separated. Air pollution is even changing the nature of families.

Livestock are covered in snow due to the effects of the dzud (Photo: United Nations Development Programme/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Government measures

In light of the above, a coal ban was finally issued in May 2019. In the short term, as an alternative to coal, semi-coke (※), which is said to emit fewer pollutants than raw coal, is attracting attention. At the same time, in the long term, a transition to electricity—especially clean energy—is anticipated. To change the lifestyle in ger districts, which are the biggest contributors to the air pollution, it would be effective either to create an environment that makes it easy for ger residents to adopt electricity or to transition households to urban housing. In fact, UNICEF, international organizations, and local groups are collaborating on a development project to create more sustainable and energy-efficient gers.

However, introducing electricity in ger districts is not straightforward. In the past, with support from the World Bank, the government has conducted distribution of low-emission stoves, but the results have been underwhelming, and people continue to use stoves that burn raw coal. This is because Mongolia, blessed with coal resources and home to more than 300 coal mines, can obtain raw coal at very low cost. Some poor households find it difficult even to purchase raw coal at about 120 yen per 15 kg bag (an average household burns two bags per night) and are forced to burn waste tires. For people who migrated to escape economic hardship, electricity is far more expensive than coal.

The cause of air pollution is by no means only the stoves inside gers; smoke emitted from thermal power plants is also a factor (Photo: Sebacalka/ Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Newly emerging rifts between rich and poor

Air pollution causes more than just health damage. Because most of the smoke originates from ger districts, friction has arisen between these peripheral areas and the city center. Some even voice extreme opinions that ger areas should be wiped out. People with the financial means are trying to escape Ulaanbaatar for the countryside or other countries, while those without such means—who moved to the capital in the first place to earn money—cannot afford to return. Environmental issues are always caught between economic development and environmental conservation, and this case of air pollution is no exception. The currently implemented ban on moving into Ulaanbaatar through 2020 clearly aims to ease the population problem, but unless efforts are simultaneously made to provide stable sources of income to people living in rural areas, it will not lead to a fundamental solution. While strengthening measures against environmental problems, a broader perspective is needed.

* Semi-coke: a solid primarily composed of carbon; because it burns more efficiently than coal, it can sustain combustion for more than 2 times longer. It also emits less smoke, though it is relatively expensive.

Writer: Yuka Ikeda

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi, Yow Shuning

モンゴルの大気汚染がこれほどひどいものだとは知りませんでした。

あまりモンゴルに大気汚染のイメージがなかったので。

首都に人口が集中していることやゾトという現象など、モンゴルについてとても勉強になりました。

モンゴルの首都でそんなに人口が集中し、大気汚染が起きていることを全く知らなかったので、びっくりしました。

大気汚染だけの問題でなく、労働問題など様々な問題が絡み合っているということがよくわかりました。一時的な対策だけでなく、長期的な対策が必要だなと思いました。

気候変動の影響で家畜が凍死してしまうというのが衝撃でした・・・。遊牧民にとって家畜を失うというのは重大なことで、生活スタイルを大きく変える要因になってしまうんだなと改めて感じました。