It is well known that Arctic ice is melting due to global warming, but in the summer of 2019, the Arctic and its surrounding regions experienced an unprecedented number of wildfires. In 2019, the total number of fires in the Arctic and nearby areas such as Siberia, Alaska(US), Greenland, and Canada exceeded 4,700, and the burned area reached 83,000 km². Experts described this as an “unprecedented abnormal situation.” Here, I will explain what caused this “abnormal situation” in the Arctic(※1), what impacts it has, and what measures are being taken.

Wildfires in Siberia (Photo: Tatiana Bulyonkova/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 ])

目次

Characteristics and mechanisms of Arctic wildfires

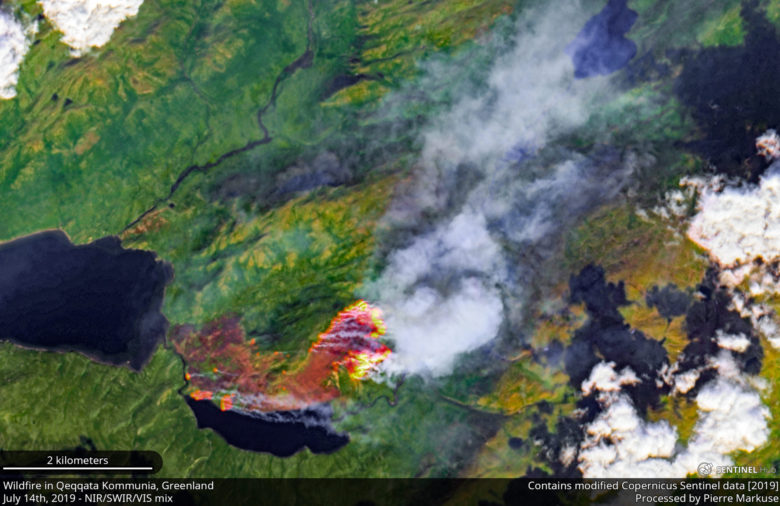

Wildfires in the Arctic are a natural phenomenon, and lightning often ignites them every year. However, unlike in the past, in 2019 the number of fires and the area burned were abnormal. At its peak in July, the burned area in Siberia exceeded 30,000 km², and the fires continued until September. The resulting smoke spread through the atmosphere to as much as 7 million km², which exceeds the total area of the EU(European Union). In Alaska, more than 10,000 km² burned, and in Greenland, a single wildfire erased as much as 375 km² of forest and grassland. Why have Arctic fires increased more than ever before? These wildfires are heavily influenced by climate change.

Warming in the Arctic is progressing at twice the rate of other regions. Several factors are driving this rapid warming, but a main cause is the reduction of snow and sea ice, which decreases the sunlight reflected by the surface and increases absorption of solar radiation, warming a larger area. As a result, the land is drying out. This phenomenon accelerates warming and creates temperature conditions that make fires more likely. For example, in July in Alaska, temperatures reached 32°C on some days, and under the combination of dry ground and higher-than-average temperatures, heat lightning and strong winds helped the fires spread rapidly.

One way Arctic fires differ from typical wildfires is that many of them are left to burn. Fires in the Arctic rarely have a direct impact on people’s infrastructure or buildings. The cost of sending firefighting crews to remote areas is high, and the affected areas are so vast that firefighting efforts often cannot keep up . As a result, fires may not be extinguished and are at greater risk of spreading further.

Arctic wildfires also have distinctive combustion behavior. In peatlands—the Arctic’s characteristic soils—low oxygen content inhibits the growth of tall trees. Because the canopy is sparse, sunlight reaches the ground easily and promotes the growth of moist sphagnum moss. Normally, peatlands are up to 95% water, which helps prevent flames from spreading. However, when warming dries the peat, it becomes highly flammable. Arctic fires do not only use trees and shrubs as fuel; when heat reaches the peat soils, the peat itself begins to burn as fuel.

While typical forest fires in the Arctic last only hours to days, these peat fires burn slowly using underground peat as fuel and can last for weeks. Because peat contains large amounts of combustible methane gas, fires can smolder for long periods even in cold, wet conditions. Furthermore, peatlands are highly prone to ignition by lightning. In fact, warming increases the number of lightning strikes, creating conditions that make fires ever more likely.

Wildfire spread by peat layers near the Baird Mountains in Alaska (Photo: Western Arctic National Parklands/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Impacts of Arctic wildfires

One problem caused by Arctic wildfires is carbon dioxide emissions. It is estimated that fires in the Arctic released 50 megatons of CO₂ in June and 79 megatons in July. This exceeds Belgium’s annual CO₂ emissions. Why are the emissions so large? Because Arctic fires spread through peat. Peat stores large amounts of carbon. In the Arctic, cold conditions slow microbial growth and decomposition, causing carbon to accumulate in the soil. It is estimated that boreal forests and Arctic tundra store 50% of the world’s soil carbon.

When this peat burns, vast amounts of CO₂ are released into the atmosphere, and it also leads to the thawing of permafrost in the layers below. Permafrost is soil or rock that remains frozen, even in summer, for at least several years. When permafrost thaws, the previously frozen soil decomposes and releases even more carbon. Peatland fires can smolder underground for long periods, melting deep layers of soil and permafrost. As a result, they burn roughly twice as much carbon as typical fires.

In recent years, permafrost thaw has created honeycomb-like depressions in the land, causing subsidence and soil collapse, which has become a problem. New lakes are forming, creating a rugged landscape known as thermokarst. Whether fire-damaged land subsides or recovers depends on how much permafrost lies beneath it. The extent of damage to the surface organic layer and post-fire weather conditions also play roles.

Thermokarst terrain in Siberia (Photo: Peter Prokosch(www.grida.no/resources/1791)/Flickr [ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

Arctic fires affect more than just soil. They release harmful pollutants and toxic gases into the air. Satellite imagery has captured dense smoke from fires in Siberia, which has spread to parts of Alaska and Canada’s west coast. The black soot (soot) in this smoke is harmful to humans and animals and can enter the lungs and bloodstream. When soot settles on white snow or ice, it reduces reflected sunlight; more sunlight and heat are absorbed by the surface, further accelerating warming.

Wildfires dry peat, which then burns; permafrost thaws; methane is released; and glaciers disappear. As temperatures rise, fires increase, black soot accumulates on ice, and warming accelerates further. This vicious cycle is likely to trigger unprecedentedly rapid climate change.

Collapsing permafrost layer (Photo: U.S. Geological Survey/Flickr[public domain])

Fires in the Arctic are also impacting ecosystems. Vast northern ecosystems are beginning to change due to fire, with new vegetation growing where it was not expected. Research in Alaska predicts that white spruce will decrease by about 30% and black spruce by about 15% due to fire, while deciduous trees will encroach. In places that were coniferous forests before the fires, young deciduous forests are beginning to grow, potentially changing the very definition of “boreal.” These vegetation changes also affect the distribution and habitats of wildlife. There are reports that caribou populations in the Arctic have halved. Caribou feed on lichens, which grow slowly and take time to recover after fire. In landscapes reduced to charred ground, caribou are unable to locate their lichen food sources, leading to population declines.

Responses to the wildfires

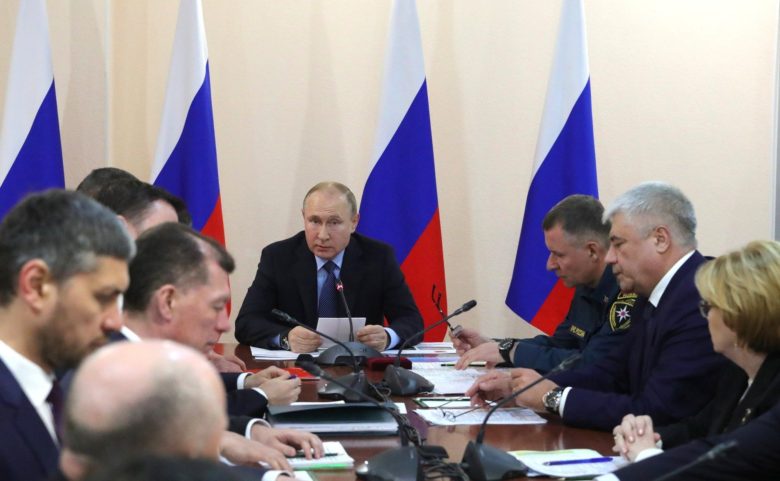

In response to fires in eastern Russia and Siberia, authorities initially stated that fires in remote areas were natural phenomena that posed no direct threat to people and that firefighting was not economically feasible. Public criticism mounted, and after a petition signed by 1 million people demanded action, a state of emergency was declared in five regions. On July 31, 2019, President Vladimir Putin ordered the military to support firefighting efforts, and 10 airplanes and 10 helicopters equipped for firefighting were sent to those areas. However, by the time the military was deployed, an area of forest about the size of Belgium had already burned, prompting continued criticism over delays and lack of funding for firefighting.

A meeting on the Siberian wildfires (Photo: President of Russia [ CC BY 4.0])

In 2019, Alberta suffered the most severe wildfire damage in Canada. Firefighters from eight other provinces, the Northwest Territories, the United States, South Africa, and elsewhere gathered to fight the fires. However, as climate change increases wildfires in the Arctic, even interregional cooperation may not keep up, posing a long-term challenge to keeping communities safe. In early August, as nearby fires prompted an evacuation advisory for Keno City in Yukon, Canada, the area’s wildfire manager said that fighting fires alone is not enough to protect the community, emphasizing the establishment of evacuation plans and investment in wildfire research that anticipates further fuel depletion.

Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, is ranked as facing a “quite high” immediate risk to public safety. Surrounded by forest, Anchorage faces a significant threat from wildfires. To address this, the city’s forest manager has coordinated programs to mitigate fire risk and is promoting Firewise(Firewise), a program that helps homeowners and neighborhoods reduce risk—by planting thinner trees around homes, installing noncombustible roofs, and ensuring firefighters can access properties quickly.

Near Sisimiut in western Greenland, a fire proved too much for local crews alone, and in August assistance arrived from Denmark to help. The fire had already been burning for about a month and threatened to spread into populated areas. If it failed to subside and continued into winter, it would further harm Greenland’s natural environment and contribute to glacier melt.

Wildfire in Qeqqata, Greenland (Pierre Markuse/Flickr [ CC BY 2.0])

Arctic wildfires are a natural phenomenon that occur every year, and because they smolder and spread in remote areas, they rarely receive major media coverage. However, in 2019 the scale of the fires reached record levels. Climate change is driving an extremely urgent crisis—and that crisis is in turn accelerating climate change. Before the vicious cycle of Arctic wildfires progresses beyond the point where we have no effective options, the world must urgently take collective action.

※1 The Arctic is the region north of 66°33‘ N. Because wildfires also occur in areas surrounding the Arctic, this article includes nearby regions as well.

Writer: Shiori Tomohara

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

北極圏というと火災をなかなか連想しません。北極圏の火災もそれほど増加したのも知りませんでした。

地域的に離れているから他人事だと思い込んでしまいがちですが、ここまで記録的な被害となると北極圏に近い国々だけでなく、世界全体で取り組むべき課題となってきますね。これから早急な対応がされることを期待したいです。

政府が消火活動に消極的なのって、同じ国土なのに見捨てられているようでひどいなと思いました。

絶望的な悪循環にかなり衝撃を受けました。遠い国の出来事ではなく、私たちの生活にも影響が出るということを、私たち一人ひとりが理解しないといけないと思います。

北極での火災がこんなにも深刻な悪循環を生み出してしまっていることにすごく驚きました。

しかも、報道されておらず、この記事を読んで初めて知ったということが自分でもショックです。

端的に言ってヤバすぎますね。