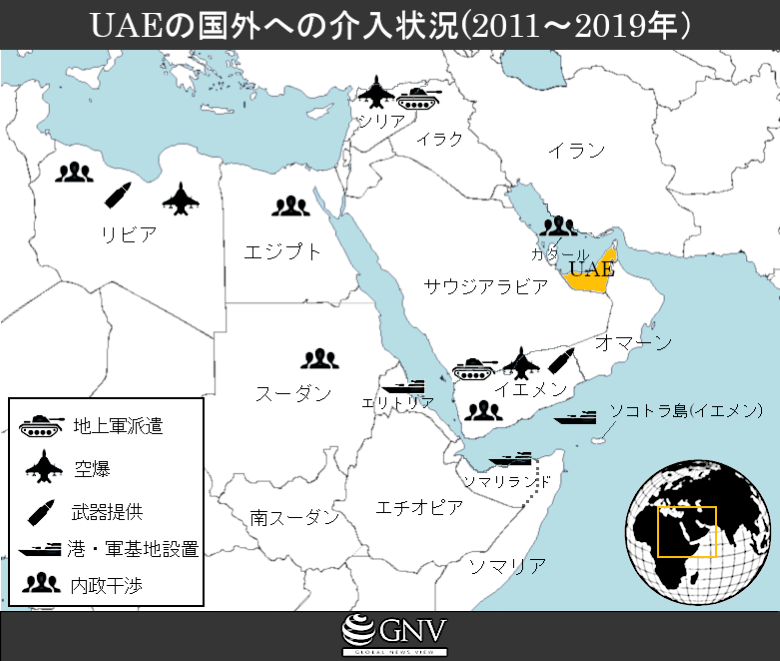

On July 3, 2019, a detention center for migrants and refugees near Tripoli, the capital of Libya, was bombed, killing at least 53 people. Libya’s interior minister asserted that it was an airstrike by warplanes of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) supporting anti-government forces, and condemned the UAE. Although the UAE has not acknowledged this, the U.S. Department of Defense and the UN Security Council indicated in 2014 that the UAE and Egypt had carried out covert airstrikes in Libya, so the possibility cannot be ruled out that this attack was also carried out by the UAE. The UAE is said to interfere in many areas—especially in the Middle East and North Africa—militarily, politically, and in other ways. What aims underlie a foreign policy that continues to intervene in so many countries? And what kinds of interventions are actually taking place?

UAE fighter jet (Photo: Aaron Allmon/Public Domain)

目次

United Arab Emirates: What is the UAE?

Before explaining the UAE’s strategies and actions in detail, we first outline the country itself. The UAE is a small country on the northern coast of the Persian Gulf on the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia. It is a federal state composed of seven emirates. After Britain announced its withdrawal from east of Suez in 1968, momentum for unification among the emirates grew; the state was founded in 1971, and the current system of seven emirates was established in 1972. The country is widely known as a source of natural resources, with proven oil reserves of about 48.3 billion barrels, the world’s 7th largest, and natural gas reserves also ranked 7th globally. Since oil was discovered in Abu Dhabi in 1959, many large oil fields have been found across the country, propelling rapid economic development. Today, it exports large quantities of oil to countries such as Japan and India.

Alongside this development, large numbers of foreign workers—especially in oil-related companies but across all industries—have come to live and work in the country. Even now, those holding UAE citizenship make up less than 12% of the total population, and the UAE has one of the highest net migration rates in the world. The country still depends on natural resources for about 30% of its GDP (2017), and in 2018 it announced economic policies aimed at a “post-oil” economy by 2021. The UAE is also recognized as a tax haven, and in March 2019 the European Union added the country to its blacklist of tax havens.

Based on Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE]

Since its founding, each emir has retained autonomy and governed his emirate under a monarchy, while the state as a whole has strongly authoritarian characteristics. Among the emirates, the capital Abu Dhabi and Dubai are the most influential, with Abu Dhabi particularly dominant. The president, regarded as the head of state, is to be selected every five years, but in practice the post has been hereditary in the Abu Dhabi ruling family; the current president, Khalifa bin Zayed, inherited the position from his father—who had served as president since the state’s founding—in 2004 and has remained at the top for more than 15 years. However, after the president was diagnosed with a stroke in 2014, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, the presumed next president, has seized authority and has controlled the state under an absolute monarchy.

Dubai has also wielded influence—for example, the post of vice president and prime minister is hereditary there—but when Dubai faced financial difficulties in the past, Abu Dhabi provided financial assistance twice, taking on a total of US$30 billion in debt, further solidifying Abu Dhabi’s position at the top in the UAE. Data support this: according to Freedom in the World, which measures political freedom, the UAE is rated low at 17 points out of a possible 100.

Moving drilling equipment at an oil field in Abu Dhabi (Photo: Guilhem Vellut/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The UAE’s foreign policy strategy

So what kind of foreign policy strategy does the UAE pursue? It is seen as having interests that lead to several proactive strategies, as described below.

First is the intention to secure routes for oil exports. As noted earlier, the UAE has long relied on oil and natural gas for much of its economy. Since exports of natural resources are central to its economy, securing export routes has been positioned as one of its most important foreign-policy priorities.

Second is countering Iran. Since its founding, the UAE has built relationships with neighboring Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab countries, as well as the United States and the United Kingdom, both highly influential in the Middle East. After the Iraq War began in 2003 with intervention by the U.S. and others, the conflict between Sunnis and Shia intensified in the Islamic world, and as Iran—predominantly Shia—sought to expand its influence in the region, the UAE came to see it as a greater threat than before. The UAE appears intent on strengthening its own influence in places such as Yemen to prevent Iran’s power from expanding there.

The “Arab Spring” also likely influenced the UAE’s foreign policy. Beginning in 2010, a wave of democratization spread as long-standing dictatorships fell one after another. Seeking to preserve its own system, the UAE came to focus on placing brakes on democratization abroad—in Egypt, Sudan, Yemen, and elsewhere—to prevent democratic movements from taking hold at home.

In addition, the UAE views armed extremist groups such as al-Qaeda and Islamic State (IS), as well as religion-centered movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood, as threats to the regime. Accordingly, as exemplified by its intervention in Syria, it has worked in various ways to build external relationships that can counter such groups.

The proactive foreign policy described thus far has been driven by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed. Because of how assertive and wide-ranging his efforts have been, he has been called the most powerful ruler in the Arab world, projecting his influence beyond the country. His foreign policy reveals a desire to gain advantage in relations with other states amid complex interests. He is particularly eager to bolster the UAE’s authority in the Middle East and North Africa. The extraordinary assertiveness of this approach becomes clear when we look at the specific interventions in other countries described in the following sections.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed meets Russian President Vladimir Putin (Photo: President of Russia [CC BY 4.0])

The UAE’s military interventions

As exemplified by the attack on a facility in Libya mentioned at the beginning, the UAE has militarily intervened in conflicts in multiple regions far from home, causing many casualties. Below are details of each intervention.

First is intervention in Libya in North Africa. The UAE’s military involvement in Libya began in March 2011, when it participated in the NATO-led military operation to overthrow the dictatorship of Muammar Gaddafi. Since then, the UAE has repeatedly interfered in Libya. In the Libyan conflict that has continued since 2014, it has intervened with airstrikes and the provision of weapons. The conflict pits the UN-backed Government of National Accord against anti-government forces known as the Libyan National Army led by former general Khalifa Haftar, along with other factions. As various countries support different sides, the UAE, in support of Haftar’s forces, established a base in early 2016, and since then is believed to have been involved in the bombing of Tripoli, the capital. In addition to military intervention, there has been weapons diversion: in June 2019, U.S.-made anti-tank missiles with UAE labels were found at a Libyan National Army base. Libya is under a UN arms embargo, and although the UAE denies ownership of the missiles, if they were imported from the United States, this would violate the UN embargo and the UAE’s purchase agreements with the U.S.

However, the UAE’s intervention has been far more extensive in Yemen. The UAE became militarily involved in the Yemeni conflict that began in 2014. The conflict originally pitted the Hadi interim government, which controlled the south, against the Houthi movement, which controlled the north including the capital, but it has been complicated by the intervention of Middle Eastern states and the expansion of al-Qaeda and IS (for details, see our previous article here). The fighting has produced many internally displaced persons and refugees, and hunger has led to severe health deterioration. In addition, the collapse of sanitation has caused disease outbreaks, among other devastating effects.

Since 2015, together with Saudi Arabia, the UAE has been at the center of a coalition against Houthi forces, engaging in full-scale intervention by supplying weapons purchased from the United States, France, Australia, and others, and by deploying ground troops. It has been revealed that among the forces sent were troops hired or brought from countries such as Colombia and Eritrea alongside UAE soldiers. The UAE may prefer not to send its own troops into harsh war zones and instead “solve” the problem by hiring soldiers if money can do so. In the chaos, the UAE has also placed the island of Socotra in southern Yemen under its control without legitimate grounds, which has become a major issue.

UAE troops in training (Photo: Ted Banks/Public Domain)

Lastly, there is intervention in Syria. In September 2014, the UAE joined U.S.-led airstrikes against IS inside Syria. Later, in November 2018, it was reported to have sent troops to support Kurdish forces in Syria. Because the Kurds are hostile to Turkey, this deployment deepened tensions with Turkey. Although the UAE participated in meetings of anti-Assad forces in the Syrian conflict that began in 2011, in December 2018 it reopened its embassy in Syria, signaling a rapprochement with the Assad regime. Alignment of interests with the Assad regime, which opposes Turkey, and the desire to weaken Iran’s influence through Syria are cited as reasons for sending troops.

While the UAE’s troops are not directly fighting in some cases, perhaps to support force deployments for the Yemen conflict, it has built military bases in the Horn of Africa—in places such as Somaliland and Eritrea—which are conveniently located along the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea between the Arabian Peninsula and Africa, and it is also building ports for economic purposes.

Diplomatic pressure and interference in domestic affairs

As noted at the outset, the UAE not only intervenes militarily in many countries, it also interferes in domestic politics and exerts diplomatic pressure. In 2017, it joined Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries in severing diplomatic relations with Qatar—seen as hostile for its support of the Muslim Brotherhood—isolating Qatar in the region. These countries severely restricted the movement of people and goods by, among other steps, refusing overflight rights to Qatari aircraft. The UAE took an especially hard line: its attorney general stated that anyone who sympathized with Qatar or opposed the UAE’s stance would be harshly punished, with the possibility of imprisonment or fines. In addition, the UAE demanded the closure of Al Jazeera, the Qatar-run broadcaster that airs in English and Arabic and has become a major global outlet.

Supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood sit in at a mosque in Cairo, Egypt (2013) (Photo: H. Elrasam for VOA/Public Domain)

The UAE has also intervened politically in African countries. Regarding Egypt, it has been revealed that the UAE deliberately fomented instability during the presidency of Mohamed Morsi—the first democratically elected leader after the Arab Spring—and financed the group that carried out the coup against him. Since then, the UAE has strengthened its ties with the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who took office after the coup. In Sudan, even when the coup against former president Omar al-Bashir was still being planned domestically, the UAE was in talks with the Sudanese military; it cut off fuel supplies and financial aid, abandoning the regime it had supported for many years and instead abetted plans to topple it, ultimately bringing an end to a 30-year rule in April 2019. After the coup, it continued to support the military as it suppressed the expanding pro-democracy movement.

What about its external strategy going forward?

In mid-2019, shifts began to appear in the UAE government’s actions. Two developments illustrate this. First, beginning in June, there was a partial withdrawal of troops from Yemen. The UAE stated the reasons were “domestic security reasons” and “strategic redeployment,” but other factors are likely at play: costs of intervention with limited gains, suspicions of arms transfers to groups linked to al-Qaeda, and concerns about allegations of abuse of detainees in southern Yemen. After the UN warned that the Yemen conflict is “the world’s largest humanitarian crisis,” this move may also have been aimed at dampening the UAE’s growing negative reputation worldwide for its hardline foreign policy and responsibility for worsening the conflict. However, the UAE foreign minister has said that although there will be a partial withdrawal, troops will remain. In addition, the Southern Transitional Council it supports has been expanding its influence, including by seizing the presidential palace, and although UAE troops have been pulled back, military support is expected to continue, leaving Yemen’s outlook uncertain.

The second development was the first talks in six years with Iran at the end of July. While the talks were described as being aimed at maritime security amid heightened tensions in the Persian Gulf, including the Strait of Hormuz, between the United States and Iran, the very fact that talks were held after a six-year hiatus suggests a possible diplomatic rapprochement with Iran.

UAE troops in formation (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense Current Photos/Public Domain)

Are these recent actions by the UAE—seemingly a softening of its stance—merely temporary tactics? Or do they represent a “change” that will lead to genuine stability? We will have to keep a close eye on the UAE’s future moves.

Writer: Taku Okada

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

We also share on social media!

Follow us here ↓

サウジアラビア以外にも、軍事介入を行い、被害を拡大させている国があると知った。

改めて”内戦”というものは存在せず、様々なアクターの利害関係が複雑に絡んで国際問題が生じるのだと思った。

自国の利益のために人道危機を悪化させる介入をどうすれば防げるのだろうか。

各国のいろんな利権が絡み合っているなと改めて思った。なのにほとんど教えられる機会もないし、伝えられない。どうしたら予防できるんだろう。

もっとこういった実態を日本で報道してほしいですね。