In October 2017, the world was shocked by video footage showing a human being bought and sold for about $400. In Libya, which has become one of the main transit points for many migrants and refugees heading to Europe, so-called “slave auctions” are taking place. The way people discuss how much to pay for the labor they need treats human beings as if they were objects.

(Photo: Kyle Cope/Public Domain)

Human trafficking refers to the transportation, transfer, handover, receipt, and exploitation of people who have been coerced or deceived into captivity, in exchange for money or other benefits. Not limited to the example of slave trading in Libya, people subjected to unimaginable conditions and routinely exploited and abused exist in almost every country in the world. According to the International Labour Organization, even today, about 40.3 million people are bought and sold as “modern slaves,” forced into brutal labor or into marriage. Such trade in human beings does not occur only within national borders; according to a 2018 UN Office on Drugs and Crime report, roughly 40% of trafficking victims are traded across borders, making this a grave problem on a global scale. Given the magnitude of this, is Japanese reporting actually conveying the current state of human trafficking to the public? Let’s look at a few data points.

目次

The global reality

Human trafficking is the trade of people in vulnerable positions for the purpose of exploitation. The methods of trafficking and exploitation vary widely, including sexual exploitation, forced labor, organ trafficking, use as child soldiers, domestic servitude, and forcing victims to commit crimes. Among these, the most frequently reported form is sexual exploitation. According to a 2018 UN Office on Drugs and Crime report, of the trafficking cases detected in 2016, those classified as sexual exploitation accounted for 59%. Sexual exploitation includes forced prostitution, forced marriage, and coerced pornography; beyond direct exploitation like prostitution, cases of earning money by using internet chats to sexually exploit a person’s body have also surged. The same report notes that the vast majority of victims of sexual exploitation are female: 68% are adult women and 26% are girls, while adult men and boys each account for 3%. Sexual exploitation is serious in both high- and low-income countries; it is a problem even in advanced economies such as Western Europe, Japan, and Australia. In North America and Central Europe, sexual exploitation accounts for over 70% of trafficking cases, and exploitation of migrants and refugees within that is a particularly serious issue.

Women subjected to sexual exploitation (illustrative photo) (Photo: ACF HHS/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Furthermore, the slave trading in Libya mentioned at the outset falls under forced labor, which accounts for 34% of trafficking victims worldwide. Many victims of forced labor are made to work in harsh conditions, for extremely low wages or no pay at all, under threats and violence. According to a UN Office on Drugs and Crime report, among victims of forced labor, 55% are adult men, 20% are adult women, 15% are girls, and 10% are boys. Regionally, the proportion of forced labor in Africa is higher than other types, with the number of victims roughly double that of sexual exploitation. In such countries, children as well as adults are often used as labor, severely depriving them of basic rights such as the right to education; this is frequently referenced in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Even in advanced economies, there are many cases of exploiting migrants and undocumented migrants as labor.

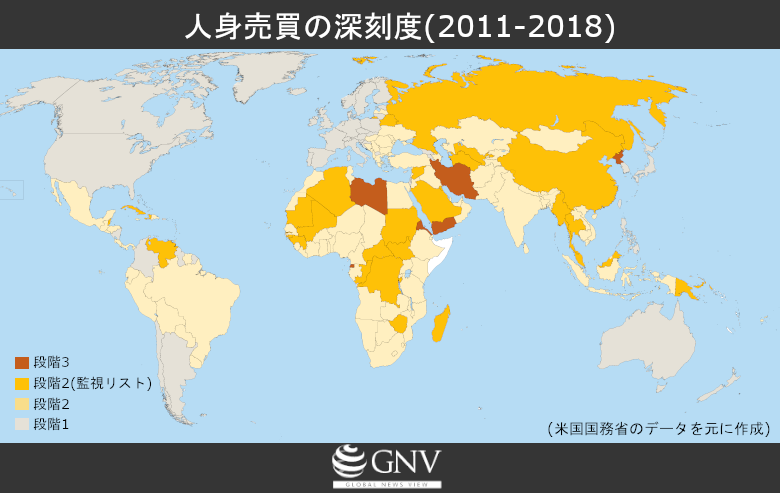

As noted above, human trafficking is a problem almost everywhere in the world, but in which regions is it particularly severe? To understand long-term trends, this article analyzed country-by-country patterns by averaging the data (※2) from the U.S. State Department that classifies countries into tiers based on the severity of human trafficking. The tiers are Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 (Watch List), and Tier 3; higher tiers indicate greater severity. The data used cover the eight years from 2011 to 2018.

Of 187 countries, 24% (46 countries) were classified as Tier 1, 55.6% (104 countries) as Tier 2, and 16.6% (31 countries) as Tier 2 (Watch List). Countries classified as Tier 3—those rated as having “the worst situation” for eight consecutive years—made up 3.2% of the total. The six countries were Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Libya, and Yemen. These results show that countries in severe situations (Tier 3 and Tier 2 Watch List) are not confined to a particular region but are scattered across the globe. However, one regional trend stands out: the burden is concentrated in countries suffering from poverty. Of the 37 countries in Tier 3 or on the Tier 2 Watch List, only two—Kuwait (33rd) and Saudi Arabia (40th)—ranked within the top 40 in the 2018 per-capita nominal GDP rankings; the rest are predominantly lower-ranked countries.

As this suggests, one major driver of human trafficking is extreme poverty. High unemployment is a persistent problem in impoverished regions; people unable to find work become easy prey for traffickers. Desperate to secure a livelihood, they may be deceived into forced labor or forced into the sex industry. In areas of extreme poverty, there are also heartbreaking situations in which parents have no choice but to sell their children to cover living expenses.

In some countries, the force of law is weakened, or perpetrators cannot be apprehended, allowing trafficking to go unchecked. Globally, as trafficking has intensified, many countries have begun comprehensive regulatory measures, and the number of convictions for those complicit in trafficking has risen in recent years. However, in many African and Asian countries, despite clear evidence of numerous victims, the number of convictions remains low. This not only allows perpetrators to go free, but also makes it harder to grasp the actual situation and hinders appropriate countermeasures.

The drivers of trafficking are not limited to poverty and failures to apprehend perpetrators. When social instability such as armed conflict undermines the effectiveness of legal order or drains resources for law enforcement, traffickers find it easier to operate. Sexual exploitation is a problem in almost every conflict in regions such as Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Armed groups use the fear created by trafficking to keep civilians under their control and gain advantage in conflict. In other words, traffickers not only profit directly from exploitation, they also use the secondary effects of trafficking as part of their strategy.

Internally displaced people who fled the conflict in Yemen (Photo: Hugh Macleod/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

The state of reporting in Japan

So, does Japanese media coverage of human trafficking capture this reality? For this article, we examined Yomiuri Shimbun issues from January 1989 to December 2018 and picked out international articles that primarily covered human trafficking (※2). What stands out, above all, is how few such articles there are. Across 30 years, only 109 articles dealt with trafficking—an average of about 3.6 articles per year. As indicated by the fact that, in the ten years from 2009 to 2018, only China and Myanmar exceeded three articles, the issue of trafficking receives very little attention in Japan. Furthermore, among the six countries that remained in the most severe Tier 3 for eight consecutive years (as defined by the U.S. State Department) during 2009–2018, only Libya and North Korea appeared in the 34 relevant articles. Of the 31 Tier 2 (Watch List) countries, only six—China, Russia, Myanmar, Syria, Malaysia, and Haiti—appeared in the articles; among the 104 Tier 2 countries, only seven—Iraq, Cambodia, Nigeria, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Vietnam—were mentioned. With so few articles, it is nearly impossible to capture the global reality of trafficking.

UNODC’s anti-trafficking campaign in Laos (Photo: Thomas Wanhoff/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

What types of trafficking are reported in Japan? Let’s first look at the attributes of victims. Over the 30 years from 1989 to 2009, 49.5 articles (45.4%) focused on adult women. Women accounted for a large share of articles on sexual exploitation in particular: of 36 articles dealing only with sexual exploitation, 27 concerned women. As noted earlier, 59% of trafficking worldwide is sexual exploitation, and most victims are female, so the fact that nearly half of the articles focused on the sexual exploitation of women does reflect the overall pattern to some extent. However, this is only a trend within an extremely small number of articles, and does not necessarily mean Japanese reporting accurately conveys the situation. For example, in Yemen, many women, including migrants and refugees, are reported to be forced into the sex industry; nevertheless, we were unable to find a single report on this.

The next largest category by article count was children, with 34.5 articles (31.7%). From the 2000s, coverage began to include the victimization of children through child pornography, as well as reports on related world conferences. In 2014, the kidnapping of schoolgirls by Boko Haram, an extremist group in Nigeria that opposes Western-style education, was reported; the group’s declaration that it would sell the girls also meant that rights to education and freedom of religion were being seriously violated—an issue that received a reasonable amount of coverage.

More recently, articles focusing on trafficking among migrants and refugees have increased. There was only one such article in the 20 years from 1989 to 2008, but in the ten years from 2009 to 2018, the number jumped to nine. Many of these rode the wave of rising interest in Rohingya refugees fleeing from Myanmar to Bangladesh, and the articles showed that multiple countries are involved in the problem and are seeking comprehensive solutions through mutual cooperation. However, exploitation that takes advantage of the precarious social status of migrants and refugees in Algeria, Niger, Sudan, and other transit countries for migrants and refugees traveling mainly from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe is not reported at all, despite evidence. This is just one example; there are countless realities overlooked in Japanese reporting.

A shrimp processing plant employing Myanmar migrant workers (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific/Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

We have examined the severe global reality of human trafficking and the situation in Japanese reporting. Human trafficking is not just an exceptional, sensational incident; it is a problem that spreads at the civic level and is deeply rooted across adverse conditions such as poverty and conflict. Even at this very moment, many people are suffering as victims of trafficking and are being continually exploited. Yet, in stark contrast to this dire situation, opportunities to encounter information about trafficking are extremely limited in Japan today. Amid today’s overwhelming volume of news, many tragic realities that should not be overlooked are being buried. It may be time to reconsider how we report on these issues.

※1 Countries that fully meet the minimum standards set by the U.S. State Department office responsible for human trafficking are classified as Tier 1. Those that do not fully meet the minimum standards but are making significant efforts to comply are classified as Tier 2. Furthermore, if, in addition to the Tier 2 criteria, (a) the magnitude of trafficking is very severe and the number of victims is increasing, (b) the country did not demonstrate increasing efforts from the previous year, or (c) the country only has plans to comply but has not yet implemented them, it is classified as Tier 2 (Watch List) requiring special monitoring. Countries that do not meet the minimum standards and are not making efforts to improve are classified as Tier 3, indicating the most severe situation in trafficking.

※2 To count each article equally, when a single article covered two themes or countries, each was counted as 0.5. For example, if an article reported on both women and children, it was counted as 0.5 for women-related articles and 0.5 for children-related articles.

Writer: Akane Kusaba

Graphics: Yow Shuning

We’re also on social media!

Follow us here:

ここまで報道されていないとは思いませんでした。

やっぱりここでも貧困が関わってくるんですね・・

人身売買は過去の世界が残した遺物だと思っていました。びっくりです。日本にいると世界はみんな平和でなんだかんだうまくいっているという誤解をしてしまうけれど、その原因を歪んだ報道が負う部分は大きいと思います。

ヨーロッパへ移民する手段として周辺国からの人身売買や密輸が現在も行われていると聞きました。EUが国境管理やパスポートチェックを厳しくすればするほど、密輸業者の必要性が高まり彼らが経済的にも潤い、逆に移民する人たちが経済的にも精神的にもますます弱い立場に置かれるということもあるようです。もっと報道されてほしい問題ですね。