In June 2019, for the first time in 43 years, there was movement on the death penalty in Sri Lanka. Executions had been under a moratorium since 1976 and had not been carried out. However, that month the president announced that four people convicted of drug crimes would be executed, said to be a measure to crack down on rampant trafficking. Alongside this, two executioners were recruited. Applicants had to be Sri Lankan men aged 18 to 45 with a “strong mind,” and as many as 100 people applied.

While there is a global move toward abolishing the death penalty, Sri Lanka is going against the tide. What, then, is the global state of capital punishment? Why do some countries retain it, and for what crimes is it imposed? Conversely, why do others oppose it and abolish it? This article focuses on these questions.

Gallows (Photo: mlhradio/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

目次

Global status and trends of the death penalty

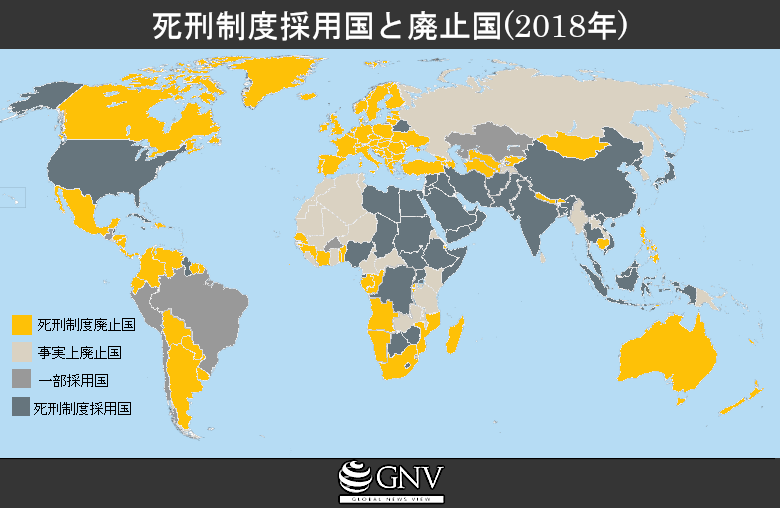

In 2018, the number of executions worldwide fell by more than 30% compared with the previous year, the lowest level in a decade. This was attributed to sharp declines in countries considered major executioners, including Iran, Iraq, Somalia, and Pakistan. The increase in abolitionist states may also be a factor. In fact, by the end of 2018, 106 countries had abolished the death penalty. Including those that retain it in law but do not carry out executions in practice, the number rises to 142. Even so, 56 countries still retain capital punishment. The countries with the highest numbers include China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Iraq (Note 1).

Based on data from Amnesty International

What kinds of crimes are punishable by death in these countries? Murder may be the first that comes to mind, but it is not the only one. The death penalty is also imposed for drug-related offenses, anti-government acts, and same-sex sexual intercourse. Methods of execution vary by country, including beheading, electrocution, hanging, lethal injection, and shooting. Let’s look more closely at the situation in individual countries.

Conditions in countries that retain the death penalty

China is believed to carry out the most executions in the world, but the actual figures are treated as a state secret and are not disclosed. Although international organizations such as the UN have demanded transparency for over 40 years, the exact number remains concealed. Only a fraction of executions are reported in the media, further obscuring the picture. In March 2018, the Supreme People’s Court announced that over the past decade it had reviewed the use of capital punishment to limit it to the most serious crimes, but it appears that thousands are still executed annually.

Next, three countries—Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq—account for a large share of the top five in terms of executions. As GNV previously reported, human rights problems in these places are severe. A common feature is the lack of fair trials. Defendants are often denied access to lawyers and may be coerced into “confessions” under torture. In Iraq, lawyers who attempted to defend defendants arrested for alleged ISIS ties were themselves arrested. Judges may also be linked to the government, undermining judicial independence. The range of capital crimes is broad, with people sentenced to death for drug offenses and adultery, same-sex sexual conduct, apostasy, or vague charges such as suspected terrorism.

A public execution site in Iran (Photo: Mohsen Zare/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0] )

Another striking feature is the use of the death penalty against people under 18. Executions of juveniles are prohibited under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Nevertheless, they occur, and the numbers are particularly high in Iran (Note 2). Courts have argued that defendants were sufficiently “mentally mature” at the time of the offense. In Saudi Arabia, too, although the case ultimately did not result in execution, a boy was arrested at age 13 and sentenced to death for alleged offenses including participating in an anti-government protest at age 10 and attending the funeral of his brother—killed during a demonstration—as a supposed member of a “terrorist organization.” Methods of execution include public beheading, hanging, and shooting.

However, the realities shared by these three countries do not apply to the entire Middle East and North Africa. In Israel, no executions have been carried out since 1962. Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco have not executed anyone since the 1990s. Many other countries have abolished the death penalty, so the region cannot be summed up by the practices of these three states.

Let’s turn to Southeast Asia. Within the region, Vietnam ranks fourth in the world for executions, with over 100 people put to death annually. A distinctive feature across the region is the frequent use of capital punishment for drug-related crimes. As GNV has previously reported, the drug problem in Southeast Asia is severe. Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, and Thailand prescribe the death penalty for crimes involving illicit drug trafficking. In the Philippines, while executions are under a moratorium, people suspected of using drugs have been killed in the streets by police, and the country is known for its “war on drugs.” In Singapore in particular, even minuscule quantities of drugs can bring a death sentence, illustrating the severity.

An airport in Indonesia. A welcome board stating “Death penalty for drug traffickers” (Photo: Jeroen Mirck/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Among OECD countries, only the United States, Japan, and South Korea continue to retain capital punishment (though South Korea has not executed anyone since 1997). While most other advanced economies have abolished it, these countries persist. What does that look like in practice?

Let’s start with the United States. Nationwide, 25 people were executed in 2018, placing the country seventh in the world. However, U.S. law varies by state. As of now, 21 of the 50 states have abolished the death penalty.

Beyond the death penalty itself, several issues stand out in the 29 states that retain it. First is racial discrimination: white defendants fare better, while African Americans are said to be treated unfairly. Second is the execution of people with mental illnesses. Although international law prohibits executing those with mental disabilities, hundreds have reportedly been put to death. Third is the arbitrariness and unfairness of court proceedings—for example, disparities in the quality of legal representation due to wealth, which disadvantage defendants.

A lethal injection gurney in the United States (Photo: CACorrections/Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Next, like the United States, Japan is among the small group of advanced economies that still retain capital punishment. In 2018, 15 people were executed—the highest number since 2008; 13 of them were former members of Aum Shinrikyo. Japan has also long been criticized for the opacity of its execution system. The government did not disclose the annual number of executions until 1998, nor the identities of those executed until 2007. Even today, execution dates are not announced in advance, and how they are decided remains unclear. In many cases, not only is there no public notice, but the prisoners themselves are informed only at the last minute after waiting for decades.

Another issue is the substitute prison system (Note 3). Although it may appear to have been eliminated in law, in practice little has changed: police are said to use it to force confessions through prolonged, harsh interrogations, contributing to wrongful convictions.

Assessing the death penalty

Having reviewed country situations, why do states retain the death penalty in the first place? One argument is deterrence: by signaling that heinous crimes will be punished by death, it is thought to prevent offending. Another is retribution against those judged to have committed crimes.

Yet numerous studies provide sound reasons to oppose capital punishment, finding that it does not function as a deterrent. For example, surveys conducted in 1988 and 1996 found no scientific evidence that the death penalty is more effective than life imprisonment at preventing crime. It is often argued that deterrence depends less on the punishment itself—death or life—than on increasing the likelihood of investigation, arrest, and conviction.

Prison cells (Photo: Thomas Hawk/Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Moreover, Iran has executed thousands of people for drug offenses since 1959, yet drug crime has not declined. Iranian authorities themselves have acknowledged that the death penalty has not worked to eradicate the country’s drug problem. In Singapore, which enforces particularly harsh crackdowns on drug crime, similar findings show that executions do not deter such offenses.

There is also the issue of cost. It is often assumed that keeping someone in prison for life costs more than executing them, but the reverse is true. The reason lies in court procedures: capital trials require greater care, often run for longer periods, and frequently lead to appeals. As a result, far more is spent on investigation, jury selection, and compensation for jurors and attorneys. Housing death-row inmates in solitary and providing heightened security are also expensive.

In practice, maintaining capital punishment means less money for other parts of the criminal justice system—for example, rehabilitation, crime prevention, and treatment programs for drug addiction.

Beyond these systemic failures, there are ethical objections. First, executions are irreversible: if someone is later found innocent, nothing can be done. In the United States, more than 160 people sentenced to death have been released since 1973 based on evidence of innocence. Worse still, there have been numerous cases where innocent people were executed.

Representatives of various religions attend an international conference against the death penalty held in Geneva in 2010 (Photo: World Coalition Against the Death Penalty/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Second is the value of human life. No matter how heinous a murder, it should not be punished by taking the offender’s life. This view also respects the right of every person to live. While retribution is often cited as a justification, it is hardly just to show that killing is wrong by killing. Some also argue that by legitimizing state killing, capital punishment brutalizes both society and government. In fact, in the United States, states that retain the death penalty have higher murder rates than those that have abolished it.

Actions and strategies of abolitionists

For these reasons, the European Union (EU) takes a strong stance against the death penalty and actively conducts outreach to promote abolition worldwide. In 1982, the Council of Europe adopted Protocol No. 6, and all then-EU member states except Russia ratified abolition. Russia has now abolished executions as well. In 1998, the EU adopted guidelines on the death penalty, signaling an intent to push for abolition not only within the EU but beyond. It urges retentionist countries to adopt moratoria and to narrow the scope of capital crimes. The EU has in fact called on Japan and the United States to abolish capital punishment.

The UN also adopted, in 1989, the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, calling for worldwide abolition. Since then, the UN General Assembly has passed several resolutions urging retentionist states to place moratoria on executions. In 2018, 121 of 193 countries supported the resolution, the highest level of support ever.

Beyond the EU and the UN, other organizations campaign for abolition, such as the International Commission against the Death Penalty (ICDP), launched under the Spanish government, and Amnesty International, which works to protect human rights. Their activities include publishing annual reports on country practices and advocating for abolition around the world.

An international conference against the death penalty held in Geneva in 2010 (Photo: World Coalition Against the Death Penalty/Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0] )

This article has outlined the realities in retentionist countries, the reasons given for using capital punishment, and the reasons for abolishing it. Today, 106 countries have abolished the death penalty—a global majority—but when Amnesty International began its work in 1977, there were only 16. This progress can be credited to abolitionist efforts. A world without capital punishment may not be a distant prospect. Countries that retain it should reconsider its purpose and effectiveness.

(Note 1) China’s total is also likely inflated by its large population. North Korea likewise keeps information secret but is said to carry out executions every year, reportedly exceeding 60 in some years.

(Note 2) Records since 1990 show 97 people under 18 executed. This is about twice the total for all other countries that execute juveniles.

(Note 3) Substitute prison: “Detaining suspects or defendants in police cells even after a detention order, when they should in principle be held in Ministry of Justice detention centers.”

Writer: Maika Kajigaya

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

死刑執行と長く刑に処するのとではどちらが罪滅ぼしになるのだろう。殺人と麻薬所持とでは比較にならないが。。罪は罪としてたとえ人に被害を加えていなくとも一瞬にして命を絶つということに

違和感を感じる。死刑執行する側の課題も近年の死刑減少に影響しているであろう。人命の尊重について改めて考えさせられた。

死刑

死刑を廃止する理由にコストなどが含まれているとは知らなかった。倫理的な理由以外にも死刑を廃止すべき理由を知ることができてよかった。

死刑のコストは終身刑より低くないし、犯罪(とくに殺人)の防止にもならないし、続けて採用することは本当に意味あるかなと思った。

抑止効果のない死刑って誰も得しませんよね(むしろ、死刑執行者にとっても死刑囚や遺族にとって損)。死刑の存在意義が全くもってないことを教えてくれてありがとうございます。

具体例や数値等を的確に引用し、丁寧にまとめられていると思います。

存続派(国)の論拠となる〝抑止力としての死刑〟に、実質整合性がないことを初めて知りました。

また、未成年や精神疾患者への死刑は国際法で禁じられていること、同時にその国際法が必ずしも守らていないことも知ることができました。

この記事で引用されているデータでは死刑を廃止した国では警察官による現場判断による射殺が増えている点を無視しています。死刑廃止国は見かけ上死刑を廃止したに過ぎないという批判もあります。

その場で撃ち殺されるかもしれないことが抑止力になっている可能性が否定できていません。この場合、死刑による抑止力と代わりないことになりませんか。

まず、引用が非常に丁寧だと感じた。続いて内容に関しては、日本が実はマイノリティである事を国外との比較によって明らかにしてくれていてわかりやすかった。普段あまり考えるきっかけのない死刑制度の是非について考えさせてくれる有難い一助となった。

改めて死刑について考えることができました。

殺人罪については被害者遺族などの気持ちを考えると、死刑を廃止するか否かという問題はなかなか難しいものだと感じていましたが、国によっては実態が不透明で罪状自体に疑問が残るようなものばかりで、そういう現状を見つめ直す必要があることをしっかり認識しました。

とても読みやすい記事でした。

ただ最近のやたら無期懲役を乱発するだけの裁判に違和感を感じるのも事実ですが。死刑が犯罪の抑止力になるかどうかは素人の自分には分かりませんが最近の裁判は意図的に被害者が望まない判決ばかりを連発している様にしか見えないので何か別の目的があるような気さえしてきます。

死刑を廃止した国では警察官による現場判断による射殺が増えているというデータを無視した研究の価値は何でしょうか。死刑廃止国は見かけ上死刑を廃止したに過ぎないという批判もありますがそれはこの点にあります。

その場で撃ち殺されるかもしれないことが抑止力になっている可能性が否定できていません。この場合、死刑による抑止力と代わりないことになりませんか。

それらの国は機動刑事ジバンの対バイオロン法「第二条機動刑事ジバンは相手をバイオロンと認めた場合自らの判断で犯人を処罰することができる。第二条補足場合によっては抹殺することも許される」の賛同国かなにかですか。

刑罰は何のためにあるのかを考えさせられました。被害者のため?被疑者のため?社会全体のため?

いろいろな考え方はもちろんあると思いますが、この議論をすること自体がもっと必要だと考えます。廃止派、非廃止派それぞれが意見をして、互いの意見に耳を傾けることができればと思います。

考えるきっかけとなりました。

私は、どうしたら犯罪が減るのかという議論の末に各国で実用的な死刑制度が導入されたと憶測していますが、改めて考えても、死刑制度は(私の小さい脳みそで)考えうる最も実用的であり、最も犯罪抑制効果のある方法ではないかと考えます。

犯罪抑制についてだけ見たら恐らく死刑制度はほとんど意味がないのでしょう。しかし、他の方法では様々な倫理的な問題が噴出したりすると思います。コストや倫理的な側面も考慮して総合的に考えないといけない死刑制度について、倫理的にほとんど問題がないし実用的だからという理由が死刑制度採用の理由として7割くらいなのではないかと推測しています。

最も、全員が納得するような或いは画期的な方法が見つかればいいのですが。この内容は継続して議論していくべき内容だと思います。

社会のため?