The 17th BRICS Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from July 6 to 7, 2025. At the summit, strengthening cooperation with the Global South was treated as a main agenda item, and the “Rio de Janeiro Declaration,” which includes 126 pledges, was signed. In addition, three plenary sessions were held under the titles “Peace and Security; Reforming Global Governance,” “Multilateralism; Economic and Financial Issues; Strengthening Artificial Intelligence,” and “Environment; COP30; Global Health.”

Since 2024, BRICS has expanded its economic scale through increases in member and partner countries. In fact, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) measured by purchasing power parity (PPP) (Note 1), the member countries accounted for about 40% of the world economy as of 2024. It is also said that in 2019, by this measure, their total surpassed that of the G7, which consists of high-income countries. In addition to regular leaders’ summits, BRICS has also launched initiatives such as the establishment in 2015 of the New Development Bank (NDB) to compete with the World Bank. In this way, backed by economic power, BRICS is building institutional foundations by creating its own financial institutions and frameworks, and expanding its global influence while bringing Global South countries into the fold.

Given this, how is BRICS being covered by the Japanese media? This article explores the volume and content of BRICS coverage in Japan’s major newspapers.

Flags of the five BRICS countries (Photo: MINISTÉRIO DAS COMUNICAÇÕES / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

目次

Origins of BRICS

The framework now called “BRICS” or “BRICS+” traces back to the concept of “BRIC” proposed in 2001 by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill. B stands for Brazil, R for Russia, I for India, and C for China. Russia then took the lead in formally creating the BRIC framework, and in 2006, at the suggestion of President Vladimir Putin, the first BRIC ministerial meeting was held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. The original purpose of BRIC was “to maintain a common position by promoting the democratization, legitimacy, and balance of the international order through dialogue on major international issues.” In 2009, the first BRIC leaders’ summit was held in Yekaterinburg, Russia. At that meeting, BRIC declared support for a multipolar international order and the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs, and proposed the introduction of a new international currency to replace the US dollar. Since the first BRIC summit in 2009, leaders’ summits have been held once a year.

South Africa joined in 2011, adding the letter S and turning “BRIC” into “BRICS.” These five countries alone account for 40% of the world’s population and more than 25% of the world’s land area, and their share of global GDP measured by PPP had risen to about 30% by 2014. At the 2012 BRICS summit, the establishment of the NDB was proposed as a financial institution to compete with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank and to provide development funds not only to member countries but also to low-income countries. The NDB’s establishment was agreed in 2014 and it officially launched in 2015. At the same time, BRICS also launched the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), a mechanism for member countries to cooperate in providing foreign currency support to one another when facing currency crises.

At the 2017 BRICS summit, as a forerunner to the “BRICS+” concept and with the aim of strengthening cooperation among low-income countries, Egypt, Thailand, Mexico, Tajikistan, and Guinea were invited as observers. This was the first time that countries other than the five existing members officially participated. Since then, inviting non-BRICS countries to the BRICS summit has become a customary practice.

Created based on Vemaps

At the 2023 summit, Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates were invited to join BRICS as full members from January 1, 2024. Of these, Iran, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia officially joined BRICS, which also came to be called “BRICS+.” Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is thought to have held off membership in consideration of its diplomatic relationship with the United States. In addition, Argentina declined the invitation to join BRICS. While the administration of former President Alberto Fernández had shown a positive stance toward joining, his successor President Javier Milei announced after taking office that Argentina would not join, reportedly in order to prioritize strengthening relations with the United States and Israel.

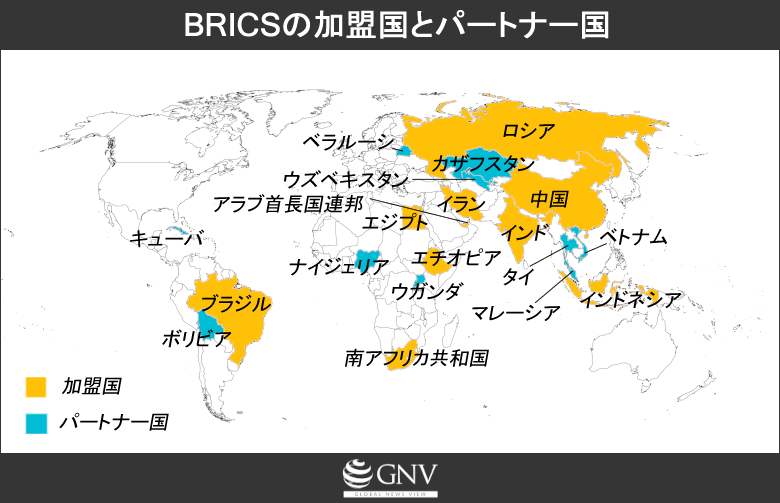

Furthermore, at the 2024 BRICS summit, the creation of partner countries was decided. Under this scheme, countries wishing to join BRICS are designated as “partners” for a certain period and then officially approved as full members after review. At that time, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Uganda, and Uzbekistan became partner countries. As of October 2024, it was reported that 34 countries had applied for full BRICS membership. Indonesia, whose membership had been approved at the 2023 BRICS summit (Note 2), also officially joined in 2025, expanding BRICS to ten countries. As a result, BRICS has come to account for about 49% of the world’s population, about 32% of its land area, and about 39% of global GDP in PPP terms, respectively.

Analysis of coverage volume

While BRICS is expanding in population and economic scale through increases in members and partners, how has it been covered in Japan? In this study, we analyzed the number of articles with “BRICS” (Note 3) in the headline and their content in the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun.

The term “BRIC” first appeared in the headlines of Japan’s major newspapers in 2004. For example, there were articles such as “BRICs: Automakers target emerging markets — aiming at 40% of the world’s population including China” (Mainichi Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2004/09/14) and “Stock investment trust targeting ‘BRICs’ (Note 4) — Daiwa Securities to start sales next month” (Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2004/06/19). From the 2000s onward, the number of articles that mentioned “BRIC” in the headline was basically only a few per year for each paper. Notably, even in 2006, when the first BRIC ministerial meeting was held, the number of such articles was limited to three in the Asahi, two in the Mainichi, and none in the Yomiuri (Note 5). In 2009, when the first BRIC leaders’ summit was held, there were about five articles in the Asahi, six in the Mainichi, and four in the Yomiuri during the year. However, as shown in the graph below (Note 6), although not in headlines, there were several dozen articles per year that included the term “BRIC” somewhere in the text.

Even after entering the 2010s, there were few articles with BRICS as the main subject, though there was a period in the mid-2010s when the number rose slightly. For instance, in 2014, there were seven such articles in the Asahi, thirteen in the Mainichi, and ten in the Yomiuri. Most of these covered the BRICS summit held that year. Many discussed the NDB, whose establishment was debated at the summit, and some compared the NDB with the IMF and World Bank. Examples include “[Editorial] BRICS development bank: Will it be a counterweight to Western-led institutions?” (Yomiuri Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2014/07/22) and “BRICS development bank established — to rival IMF and World Bank; lending to begin in 2016” (Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo evening edition, 2014/07/16). From the late 2010s through 2021, there was no significant increase in headline counts.

From 2022 onward, coverage surged in each paper, with 2023 seeing a record-high number of headlines for all three. This was likely driven mainly by BRICS moving forward in earnest with its “expansion plans,” including accepting new members. Some articles also pointed out that since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while G7 countries have tightened unity vis-à-vis China and Russia, BRICS aims to strengthen a framework to counter the US and Europe.

Next, we take a closer look at the trend in coverage volume (Note 7) during the week before and after each year’s BRICS summit. Here, we counted not only headlines but also articles that mentioned “BRIC” or “BRICS” in the text.

As noted above, the increase in coverage in 2014 likely reflects attention to debates over establishing the NDB at that year’s summit. In 2017, the coverage included reports on China and India — both BRICS members — agreeing to withdraw troops in their border dispute. For example, “China and India move toward troop withdrawal along the boundary; agreement reached ahead of summit” article and “China–India agree on border troop withdrawal; India issues statement ahead of BRICS meeting” (Yomiuri Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2017/08/29). There were also pieces focusing on BRICS’ response to North Korea’s nuclear test, such as “BRICS joint declaration: On North Korea, only ‘regret’; China prioritizes a successful summit” (Yomiuri Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2017/09/05). In 2023 and 2024, as mentioned, stories related to BRICS expansion plans drew attention.

Comparison with the G7

At the outset, we touched on the economic sizes of BRICS and the G7. In global GDP share measured by PPP, as of 2024 the G7 accounts for about 29% and BRICS for about 40%. In terms of population, the G7 has around 10% while BRICS accounts for 40–45% of the world’s population. With the accession of Iran and the United Arab Emirates, BRICS has also come to account for about 40% of global oil production, by some estimates. Beyond oil, BRICS is said to hold a large share of global natural resources such as natural gas and rare earths, as well.

While BRICS’ economic scale and global influence may now rival the G7, how do the two differ in media attention? This time, we measured the average number of headlines for both “G7” and “BRICS” in the Asahi and Mainichi and examined the content (Note 8).

As the graph shows, in every year the number of G7 articles is overwhelmingly greater than that of BRICS. This contrast is especially pronounced in 2016, likely because the G7 summit was held in Ise-Shima, Japan. In concrete terms, “G7” averaged 256 articles, while “BRICS” averaged 4.5 — a gap of about 57 times.

In 2022 and 2023, G7 coverage appears to have increased in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and particularly in 2023 due to the G7 summit held in Hiroshima. Meanwhile, although BRICS’ expansion plans drew attention in 2023 and the Asahi and Mainichi recorded their highest-ever BRICS headline counts, they still fell far short of G7. In fact, “G7” averaged 483.5 articles, whereas “BRICS” averaged just 18 — a gulf of about 27 times. While BRICS does attract media interest on certain themes, its overall coverage remains extremely limited compared with the G7.

So far we have looked at headlines; what about mentions? We calculated (Note 9) the difference in coverage of the G7 and BRICS over the five years from 2020 to 2024. In the Asahi, there were 2,943 articles that mentioned “G7” and 125 that mentioned “BRICS.” In the Mainichi, there were 3,223 “G7” mentions and 129 “BRICS” mentions. In the Yomiuri, there were 4,916 “G7” mentions and 200 “BRICS” mentions. Compared with BRICS, the G7 was covered about 24 times more in the Asahi, about 25 times more in the Mainichi, and about 25 times more in the Yomiuri.

Scene from the 2024 BRICS summit held in Russia (Photo: Press Service of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Why isn’t BRICS covered?

As we have seen, despite BRICS’ large economic and population scale and significant global influence, it receives relatively little coverage in Japan’s international reporting. Several factors may explain this. First, Japanese news outlets often approach international reporting from a self-centered perspective. Unlike the G7, Japan is not a BRICS member, which tends to reduce media interest in BRICS.

In addition, as discussed in a previous GNV article, Japanese media not only show strong interest in the United States but are also easily influenced by issues the US government and media highlight. As a result, the fact that BRICS is not prominently covered in the United States likely contributes to its lower prioritization in Japanese media.

A similar tendency can be observed regarding the “Global South” more broadly, not just BRICS. BRICS is a group centered on Global South countries, and Japanese media interest in the Global South is extremely low. Not only in Latin America and Africa, but also in South and Southeast Asia, the volume of coverage is relatively small. While Japanese media show strong interest in China, coverage volume suggests relatively low interest in other BRICS members and partners.

Analysis of BRICS coverage in 2025

We now look at how the BRICS summit held from July 6 to 7, 2025, was covered. During the week before and after the summit (June 29–July 14, 2025), “BRICS” appeared in headlines five times in the Asahi, five times in the Mainichi, and eight times in the Yomiuri. Many articles referred to BRICS’ political positioning.

For example, the Asahi carried an article titled “BRICS in step with Russia; criticizes Ukraine’s counteroffensive; joint declaration,” and the Yomiuri ran an article titled “BRICS tones down anti-U.S. stance… summit declaration shows difficulty in agreeing on a ‘confrontational line’.” On the Russia–Ukraine conflict, they reported that Russia aligned with other BRICS countries. At the same time, coverage noted that BRICS did not explicitly criticize the United States by name over President Donald Trump’s tariff policies. There was also reporting that, on climate change, BRICS pressed high-income countries to take responsibility. Examples include the Asahi article “Demanding more climate finance; emphasizes responsibility of advanced countries; BRICS” and the Yomiuri article “BRICS summit: ‘Advanced countries should contribute’ to climate action; declaration adopted and summit closes.”

Group photo of the 2025 BRICS summit (Photo: Prime Minister’s Office / Wikimedia Commons [GODL])

Thus, a number of articles framed the BRICS summit from the perspective of high-income countries such as the United States. Counting articles from January 2025 through one week after the summit, July 14 (Note 10), in the Mainichi, five of nine total articles and, in the Yomiuri, six of sixteen total had headlines focusing on the United States, with terms such as “U.S.,” “America,” or “Trump.” No such headlines were observed in the Asahi. Meanwhile, issues actually discussed at the summit — strengthening ties with the Global South, climate change measures, promoting digital technologies, and designing frameworks for AI use — were not often highlighted in headlines. This suggests relatively low interest in BRICS itself.

Conclusion

Japanese media have traditionally referred to the G7 as the “major countries” and, in coverage, have placed overwhelming emphasis on the G7 over BRICS. This bias may stem from a persistent perception of a US-centered unipolar world. In reality, the world is shifting toward multipolarity, with groups of low-income countries, starting with BRICS, gaining influence. Given that Japan is a G7 member, it is understandable that media prioritize G7 developments. Even if BRICS’ cohesiveness is not yet especially strong, the fact remains that BRICS exerts a substantial influence on the world, yet receives extremely limited coverage. This suggests Japanese media may not be adequately reporting the progress of global multipolarization.

We will be watching to see how Japanese media respond to further BRICS expansion and the accompanying changes in the international order.

※1 A rate that shows how much goods purchasable at a certain price in one country would cost in another country (an exchange rate based on the prices of goods and services). In growing economies, as employment expands and wages rise, personal consumption tends to be robust and purchasing power increases. GDP measured in PPP terms is used to reflect such differences in purchasing power, and is considered an indicator that allows comparison of real economic sizes by taking each country’s price levels into account. By contrast, nominal GDP represents economic size using market exchange rates and does not consider changes in each country’s prices. In low-income countries with lower prices and undervalued currencies, nominal GDP tends to appear smaller than actual economic conditions would suggest.

※2 The other six invited countries (Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) were invited with an effective joining date of January 1, 2024. Indonesia, on the other hand, was invited without a set joining date, and after its presidential election, its full membership was confirmed in 2025.

※3 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi/Yomiuri, we counted the number of articles whose headlines included the term “BRIC” from 2004 to 2010, and “BRICS” from 2011 to 2024.

※4 The “s” in BRICs initially carried the sense of a plural referring to multiple countries — Brazil, Russia, India, and China — experiencing remarkable economic growth.

※5 Although “BRIC” did not appear in the headline, there was an article titled “China, Russia, and India hold summit; confirm strengthening cooperation” (Yomiuri Shimbun, Tokyo morning edition, 2006/07/18).

※6 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi/Yomiuri, we counted the number of articles whose headlines or texts included the term “BRIC” from 2004 to 2010 and “BRICS” from 2011 to 2024.

※7 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi/Yomiuri, we counted the number of articles whose headlines or texts included the term “BRIC” from 2009 to 2010 and “BRICS” from 2011 to 2024.

※8 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search” and Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi, we counted the number of articles whose headlines included “BRIC” and “G7” from 2004 to 2010, and “BRICS” and “G7” from 2011 to 2024. Because the Yomiuri database does not allow headline-only searches, we omitted it from this query. For each of “G7” and “BRICS,” we calculated averages to better show coverage trends, taking into account data variability.

※9 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi/Yomiuri, we counted the number of articles whose headlines or texts included “BRICS” or “G7” from 2020 to 2024.

※10 We used the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mai-Saku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas.” Among articles published in the morning and evening editions (national and local) of the Asahi/Mainichi/Yomiuri, we counted the number of articles whose headlines included the term “BRICS” from January 1, 2025 to July 14, 2025.

Writer: Hayato Ishimoto

Graphics: Ayane Ishida

[2764]Jili33 Online Casino Philippines: Top Jili33 Slots, Easy Login, Register & App Download Experience Jili33 Online Casino Philippines! Enjoy top Jili33 slots, easy Jili33 login, fast register, and the official Jili33 app download. Join now for big wins! visit: jili33

[1882]agg777 Online Casino Philippines: The Best Online Slots & Legit GCash Gambling Hub. Experience **agg777 online casino Philippines**, the premier destination for the **best online slots agg777** and **top live dealer casino Philippines** action. As the leading **legit online gambling GCash Philippines** hub, we provide secure transactions and massive jackpots. Complete your **agg777 login and registration** today to enjoy a world-class gaming experience with instant payouts! visit: agg777

[9712]39 Casino Philippines: Official 39 Login, Slot & Register. Download Now for the Best Online Gaming Experience. Experience the best online gaming at 39 Casino Philippines. Quick 39 login, premium 39 slot games, and easy 39 register. 39 download the app now to start winning today! visit: 39

[585]Jili56 Casino Philippines: Jili56 Login, Register & App Download for Top Jili56 Slot Action. Experience the ultimate gaming at Jili56 Casino Philippines! Quick Jili56 login & register to play top Jili56 slot games. Get the Jili56 app download for non-stop casino action today. visit: jili56

[2028]Philippines’ Top Online Casino: Easy sa88 Login, Register, & App Download. Play the Best sa88 Slot & Live Casino Games Today. Experience the best of sa88, the Philippines’ top online casino. Quick sa88 login & sa88 register. Get the sa88 download for mobile and play sa88 slot or live casino games today. Join sa88 casino now! visit: sa88

[1707]SolaireOnline Casino Philippines: Official Login, Register & App Download for Premium Slots Experience SolaireOnline Casino Philippines! Quick solaireonline login and register to play premium solaireonline slots. Get the official solaireonline app download for the best mobile casino gaming experience today. visit: solaireonline

[2981]Wagiplus Philippines: Best Online Slot & Casino – Login, Register, and App Download Official Link Join Wagiplus Philippines, the best online slot & casino site. Secure Wagiplus login, fast Wagiplus register, and official Wagiplus app download. Use our Wagiplus casino link for premium slot online games today! visit: wagiplus

[8909]xx777: The Best Legit GCash Online Casino in the Philippines for Slots & Live Dealers Experience the ultimate gaming thrill at **xx777**, the best **legit GCash online casino in the Philippines**. Discover a massive selection of **xx777 slot games and live dealer** options on the most trusted **online gambling platform in the Philippines**. Ready to win big? Complete your **xx777 login and register** today for fast GCash payouts, secure transactions, and a premium casino experience! visit: xx777

[470]PH163: The Premier Online Casino in the Philippines for Best Slots and Fast GCash Payouts. Experience the ultimate gaming at **PH163**, the premier **online casino Philippines** known for offering the **best online slots Philippines** and lightning-fast **GCash payouts**. Access your favorite games securely via the **PH163 login** and discover why we are the top-rated **GCash casino PH** for reliable, high-speed wins and premium entertainment. visit: ph163

[3783]Masaya365: The Best Online Casino in the Philippines. Quick Masaya365 login, register, and sign up. Experience top Masaya365 slot games and easy app download today! Join Masaya365, the best online casino in the Philippines! Enjoy quick Masaya365 login, register, and sign up to play top Masaya365 slot games. Experience seamless gaming with our easy Masaya365 app download today. visit: masaya365