More than half of the world’s population is in what is commonly referred to as a “state of poverty.” Poverty is an extremely complex social phenomenon in which various factors are intricately intertwined. In some cases, internal factors such as communities where poverty is widespread and social, economic, and political problems at the national level are at play, while there are also external factors such as historical negative legacies and the still-ongoing unfair global trade system. GNV has long published many articles and podcasts that try to understand poverty at a global level. This time, we pick up several archived GNV articles related to poverty, excerpt some of their content, and look back on this major issue.

目次

The difficulty of understanding poverty

Poverty is hard to measure and is not merely a matter of “money.”

The forms of “poverty” vary widely by place and circumstance. In thinking about poverty, we need to look not only at the presence of food, clothing, and shelter, but also at air and water quality, as well as the state of healthcare and education. This means people’s situations differ not only by personal income, but also by the welfare systems and other support provided by governments. Poverty as seen by a farmer living a largely subsistence life with little cash is different from poverty as seen by an unemployed person living in a low-income urban neighborhood. It also differs by gender, age, disability, health status, and access to education. There are many aspects that only those living in such conditions can truly understand. Poverty appears in many forms, often referred to as “multidimensional poverty.”

“How should we interpret the state of global poverty?” October 28, 2021

However, there are also numbers that represent poverty. One approach, for example, is to count people living below a certain income threshold.

Since 2015, the World Bank has defined extreme poverty as living on $1.90 a day or less. First set at $1.00 in 1990, this line has been raised gradually to keep pace with inflation, and was originally determined from the average of poverty lines in 15 low-income countries.

“How should we interpret the state of global poverty?” October 28, 2021

Shopping in East Lombok, Indonesia (Photo: Asian Development Bank / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Since 2022, the World Bank has raised the extreme poverty line to $2.15 a day. But there is criticism that this amount is far too low.

Even if it were $5.50 a day (about $170 a month) or $10 a day (about $310 a month), how feasible would daily life be? In response to these income thresholds whose rationales do not necessarily match reality, some researchers propose an “ethical poverty line.” This standard is based on the relationship between life expectancy and income, identifying the point at which the income available for living falls so low that survival rates drop sharply. In other words, while the World Bank’s extreme poverty line and similar thresholds are calculated from poverty lines in multiple countries, the ethical poverty line sets a minimum based on whether survival can be guaranteed. In that sense, it could be called an objective and reasonable extreme poverty line because it uses “staying alive” as its criterion. As of 2015, that line was estimated at $7.40 a day. According to the World Bank’s 2014 data, more than half of the world’s population (56.8%) lived below this income level.

“How should we interpret the state of global poverty?” October 28, 2021

Inequality

As noted, more than half of the world’s population lives in poverty. Meanwhile, wealth is concentrating in a few countries, corporations, and individuals.

What kinds of inequalities exist in the world we live in today? According to the 2019 edition of Oxfam International’s annual report on inequality released each January, the combined wealth of roughly 3.8 billion people—the bottom half of the world’s population—was equal to the combined wealth of just 26 billionaires at the top. Moreover, in 2018, while the wealth of those 3.8 billion people fell by 11%, billionaires with assets of over $1 billion continued to grow their wealth at a pace of $2.5 billion per day. Furthermore, according to the annual report by Swiss financial firm Credit Suisse, 45% of global wealth is monopolized by just 1% of people worldwide.

“Global inequality: the current situation and its background” December 26, 2019

Even if poverty in low-income countries improves to some extent, the bulk of the wealth generated globally flows to high-income countries.

“How should we interpret the state of global poverty?” October 28, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has further widened this inequality.

The rapid expansion of global inequality during the pandemic is beyond imagination. World Bank data show that in 2020 alone, 97 million people fell into extreme poverty. Looking at the global population as a whole, the number of people in extreme poverty increased for the first time since 1998, which the World Bank calls “an increase unprecedented in recorded history.”

That same year, the wealth that flowed into the hands of the world’s billionaires skyrocketed by an astounding approximately $4 trillion, according to the World Inequality Lab. This surge in billionaire wealth was also a record increase, marking the highest amount in 25 years of records. While these two phenomena are not entirely directly connected, there is no doubt that the gap between the poor and the wealthy has widened on a global scale—an extraordinary trend in the world economy.

“Why don’t the media report on the rapid rise in global inequality?” February 24, 2022

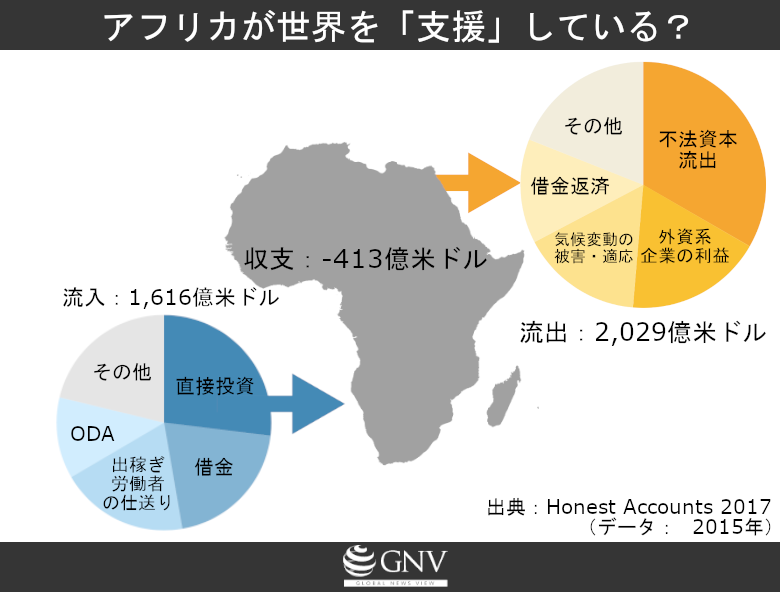

As a result, when you add up all financial flows—trade, aid, debt and debt repayments, and more—more money is currently flowing out of the African continent than into it.

“Global inequality: the current situation and its background” December 26, 2019

Capital outflows

One factor behind this inequality is capital outflows. Tax avoidance and tax evasion in the course of trade deal a heavy blow to low-income countries.

$1.3 trillion. That is the total amount of corporate profits shifted to tax havens worldwide. This figure was estimated by the UK-based NGO Tax Justice Network (Tax Justice Network), which addresses tax haven issues. Corporate income tax is levied on company profits, but profits are shifted from the country where economic activity actually occurs and profits are earned to a tax haven with little real economic activity, making it appear as if profits were earned there. This allows companies to avoid the corporate taxes they would otherwise owe. Tracking these shifted profits, the estimated global tax loss amounts to a staggering $330 billion.

“Tax havens and the islands around the Caribbean” August 27, 2020

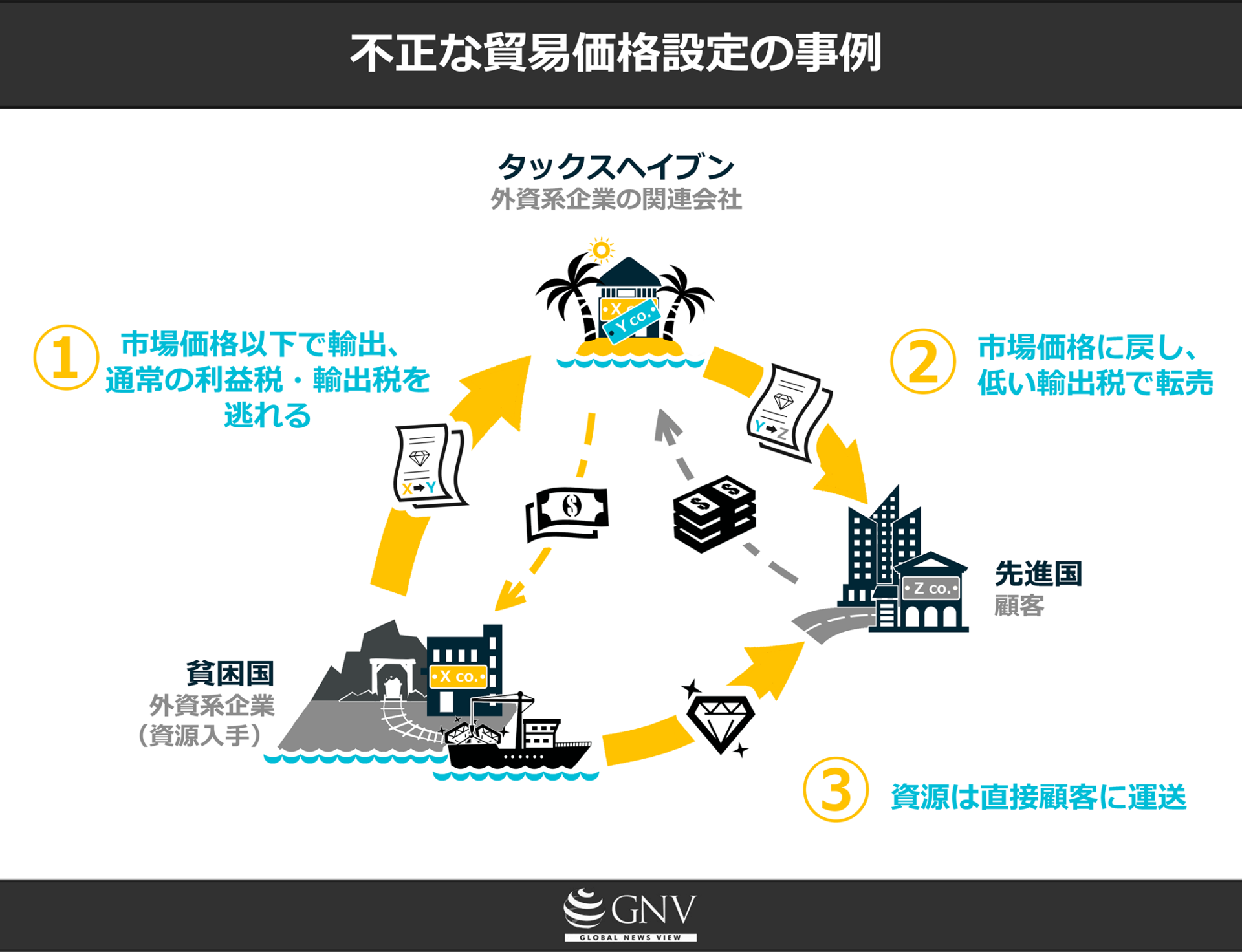

Legally arranged profit shifting is a major problem, but the losses from illicit financial outflows are also estimated to be enormous.

Many companies operating in the poorest and developing countries are thought to employ various illegal methods to reduce their tax payments. For companies that export natural resources or products, a common tactic is to overstate extraction or production costs, or understate export prices, to make their profits appear lower.

In this context, trade mispricing and trade misinvoicing stand out. For example, when a foreign company extracts mineral resources in a poor country and exports them, it first “sells” the minerals at a price far below market value to an affiliate located in a low-tax jurisdiction (a tax haven) to avoid profit taxes and export duties that should be paid in the poorer country. Then the affiliate in the tax haven restores the mineral price to a normal level and “resells” it to the actual customer in a high-income country. The minerals themselves do not physically pass through the tax haven; they are shipped directly from the poor country to the customer. To conceal the fact that the company in the tax haven is an affiliate, multiple shell companies may be established and corporate relationships made deliberately complex.

“A major hidden factor blocking poverty reduction: illicit financial flows” January 19, 2017

“A major hidden factor blocking poverty reduction: illicit financial flows” January 19, 2017

Unfair trade

Exploitation arising from the power relationship between buyers and sellers in trade is also widespread.

As a hotbed of unfair trade, pricing must first be considered. In retail settings, sellers generally set the price and buyers purchase at that set price. However, in many primary commodity production sites, the exact opposite happens: buyers set the price. Behind this lies a survival-of-the-fittest system in which pricing in global trade for primary commodities is influenced by power. Those who move more capital and goods can influence prices. Let’s take a simplified example of the food-relatedvalue chain (value chain). Looking at shares of the final price in descending order of “power,” they are retailers, manufacturers, trading companies, and producers. In other words, producers have virtually no say in pricing.

Not only for food but for primary commodities in general, it is often the buyer—not the seller—who sets the final product price, contrary to typical transactions. When a major tobacco company buys tobacco leaves from producers in Malawi, for example, the manufacturer evaluates the product’s quality and unilaterally sets the price to suit its own needs. This system is also seen in India’s cotton industry and Madagascar’s vanilla industry, and is a common structure especially for goods purchased from low-income countries. Producers, who can hardly participate in price setting, are put at a disadvantage, leading to exploitation.

“Unfair trade rampant around the world” March 10, 2022

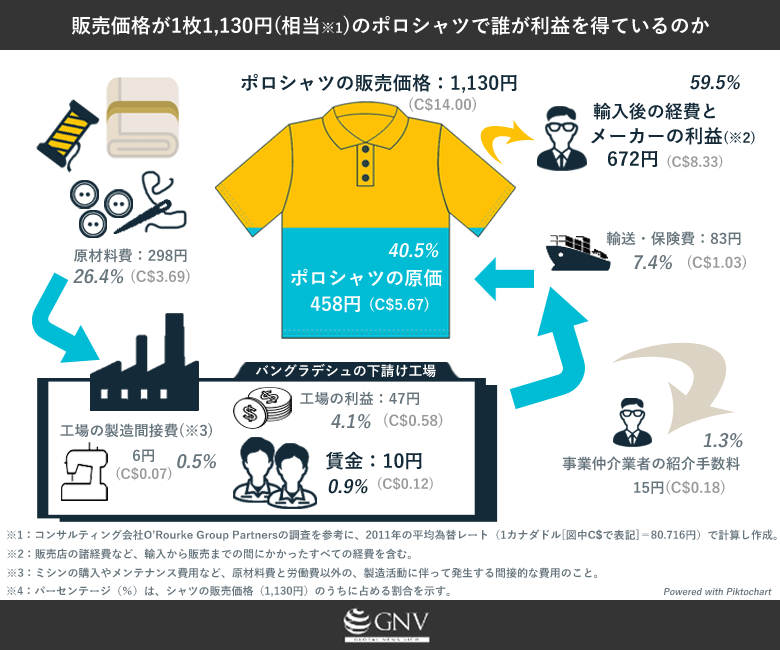

As a result, only a small fraction of the product price remains in the hands of producers, while most of the price becomes profit for manufacturers and retailers. The fashion industry is one such sector where this phenomenon is evident.

“The ‘underside’ of the fashion industry” October 19, 2017

Toward improvement?

As we have seen, reducing global poverty and inequality requires cracking down on tax havens and capital outflows while making global trade fairer. However, how far are high-income countries, which benefit from the current unfair economic system, willing to pursue reform?

Issues stemming from tax havens are frequently the subject of international debate, and at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD3) in 2015, institutional reforms at the level of international organizations were on the agenda. However, these did not materialize due to strong opposition from high-income countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. Other approaches include tax policy. At the domestic level, higher income tax rates can help redistribute wealth and reduce inequality. At the international level, ideas include the “Tobin tax,” which would tax foreign exchange transactions to curb speculative profits and allocate the revenue to support low-income countries, and the “air ticket solidarity tax” levied on international flights that has been adopted in France and several other countries. However, each of these faces obstacles: higher income taxes encounter pushback from economically powerful elites domestically, and the Tobin tax faces opposition from high-income countries. As for the problem that low-income countries cannot add value in international trade, promoting industrialization can be considered. Yet given how far behind they are, it is hard to imagine they could become competitive with already established manufacturing giants. Moreover, reconciling industrialization with climate change mitigation is a major challenge.

“Global inequality: the current situation and its background” December 26, 2019

GNV will continue to examine the issue of global poverty from a worldwide perspective.

0 Comments