Society and politics in Latin America are in flux. As GNV previously covered, political conditions across Latin American countries have remained unstable. Behind this are industrial structures carried over from the colonial era, repeated economic crises, and deteriorating public security. Corruption and inequality have become more apparent, and more countries are questioning the very existence of democracy.

This time, we have selected three articles from The Conversation to help deepen understanding of Latin America under such conditions.

Voting in Ecuador’s National Assembly: Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

In Latin America and the Caribbean, despite severe challenges, democracy is still supported

“Translated article from The Conversation,” by Noam Lupu, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, and Luke Plutowski (original) (Note 1)

Across Latin America and the Caribbean, threats to economic and physical security are deeply entrenched, shaping how people view the state of democracy in the region.

These are the latest findings from the AmericasBarometer, a survey conducted biennially by Vanderbilt University’s LAPOP Lab on people’s experiences and attitudes across the Western Hemisphere (AmericasBarometer).

The 2023 survey covered 39,074 people in 24 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and reveals widespread pessimism and adversity, along with declining satisfaction with the status quo.

Rising economic and physical insecurity

Across the region, just under two-thirds (64%) of adults think their country’s economic situation has worsened. Strikingly, 32% report having run out of food in the past three months, an indicator of food insecurity consistent with estimates reported by the Pan American Health Organization.

Two in five feel their neighborhoods are unsafe, and nearly a quarter—22%—report being victimized by crime in the past 12 months. The region’s homicide rate is also rising.

In short, while there are differences across countries, the survey shows that the average resident has faced economic and physical security challenges for more than a decade.

The factors creating and sustaining these realities are complex.

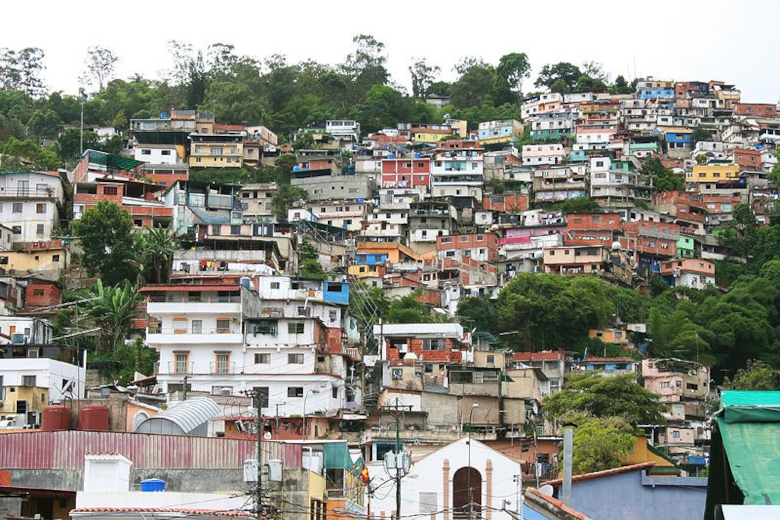

Residential area in Caracas, Venezuela (Photo: Samout3 / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In the mid-2010s, the global commodities boom ended, and the region’s economic recovery has been hindered by structural problems such as low productivity and high income inequality. Recovery has been further hampered by large-scale corruption scandals, crime and violence, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impacts of persistent stagnation are severe. In nearly every country in Latin America and the Caribbean, food insecurity has increased over the past decade.

Rising crime and insecurity likewise stem from various factors, including economic crises and the growth of armed transnational criminal organizations. In Ecuador, as an extreme example, 36% of adults report being victimized by crime at least once in the past year—an increase of 11 percentage points compared with just two years ago.

Disillusionment challenges democracy

These problems can spell trouble for democracy in the region.

Some experts predict that economic and food insecurity could fuel political instability in the coming years. The threat of violence from organized crime and gangs may also stoke a desire for authoritarian leadership.

Globally, democracy appears to be on the defensive. In Latin America and the Caribbean, countries such as Brazil, El Salvador, Haiti, and Nicaragua have recently tilted toward authoritarianism.

According to the survey, disillusionment with the current state of democracy is strikingly high: only 40% think democracy is working. Such low satisfaction has also been seen in surveys over the past decade.

While the root causes are still being debated, disillusionment with the status quo is fueling support for populist leaders with authoritarian tendencies. El Salvador illustrates how disillusionment can corrode democracy. On February 4, 2024, President Nayib Bukele won reelection with more than 80% of the vote, despite his brazen violations of democratic norms.

During his first term, Bukele tackled high levels of gang violence with policies that undermined checks and balances and civil liberties. He has called himself a “dictator” on social media, and his running mate has spoken of a program to do away with democracy.

Bukele’s heavy-handed approach has produced undeniable results. According to the survey, 84% of Salvadorans feel their neighborhoods are safe. In 2018, the year before Bukele was elected, only 54% felt that way. Food insecurity remains a challenge, with 28% reporting they have experienced shortages. However, that statistic was slightly lower in 2023 than in 2012, in contrast to the upward trend in almost every other country.

Democracy retains public support

Despite generally bleak views of how well democracy is functioning, there is room for optimism. Support for democratic governance has been nearly stable across the past decade of surveys.

Across the region, on average 58% say democracy is the best form of government. That share is almost the same as in surveys conducted since 2016. In all countries except Guatemala, Honduras, and Suriname, a majority prefer democracy.

There is a possibility of democratic backsliding, but most countries in the region have not yet undertaken major overhauls of their political and economic systems. As former ambassadors of Peru, Colombia, and Brazil to the U.S., P. Michael McKinley noted in a recent article, radical proposals by new leaders in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have been unpopular and were rejected by voters, courts, and legislatures. In these cases, democratic institutions are fulfilling their role.

Democratic governance also brings something absent in authoritarian populist regimes: broad freedom of expression.

The 2021 regional report of the AmericasBarometer highlighted that citizens value free speech. An overwhelming majority say they would not trade freedom of expression for material well-being.

In 2023, in countries with authoritarian populist leaders, those who do not support the president showed surprisingly high levels of concern about free speech. In El Salvador, 89% of government critics say there is too little freedom to express political views without fear—up from 70% in 2016.

Facing serious challenges, Latin America and the Caribbean stand at a crossroads between the appeal of strongman populist leadership and a commitment to democratic institutions and processes. For now at least, steady faith in democracy may be encouraging the efforts of leaders inside and outside the region to support and strengthen democratic governance.

Deep-seated inequality is fueling an escalation of violence across Latin America

“Translated article from The Conversation,” by Andrew Nickson (original) (Note 2)

For much of the 20th century, Latin America was portrayed as one of the most peaceful regions in the world. Coups and repressive military regimes were long commonplace, but widespread civil strife and wars were relatively rare. Today, however, the global media is gradually waking up to a very different reality.

With violence levels surging, mortality rates in Latin America often exceed those seen in conflict zones. In 2021, the region’s homicide rate was the highest in the world—about three times the global regional average.

Ecuador is one of the countries where violence has risen particularly sharply in recent years. On January 9, 2024, a masked armed group stormed a live news broadcast, and the prosecutor investigating the attack was killed just days later.

This explosion of violence in the region is driven by many mutually reinforcing factors. In particular, deep-seated inequality and weak states have allowed an unstable drug economy to thrive.

Enduring inequality

Latin America has long been the most unequal region in the world in terms of income and wealth. But this inequality has worsened in recent decades. In 2021, the richest 1% in Brazil owned 47% of the nation’s wealth, up from 45% in 2006. The share owned by the top 0.01% rose from 12% to 18%.

Unlike other middle-income regions, the region’s economic structure is still based on primary commodity exports, which have changed little since colonial times. This dependence is deepening as Latin America responds to increased demand for minerals and food from China.

Reliance on primary commodity exports has reinforced inequality, as the expansion of large-scale commercial agriculture and mining has impeded moves toward agrarian reform.

As a result, there has been a surge in graduates migrating to cities in search of work. However, because the model is capital-intensive, serious attempts at industrialization and labor-intensive job creation—seen in much of South and Southeast Asia—have been held back.

The long history of anti-communism pushed by successive U.S. administrations during and after the Cold War, together with a Catholic Church that has become deeply conservative in recent decades, has also hindered attempts at social-democratic reform and inclusive development. As a result, revolutionary movements advocating progressive agendas capable of delivering the structural reforms the region desperately needs have collapsed.

The outcome is pervasive underemployment, a major factor behind the surge in irregular migration to the United States. More than half of workers in Latin America are informally employed, with insecure jobs, low incomes, and no social protection.

Miners in Bolivia: Viaje a Bolivia / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

The illegal drug trade

In recent decades, however, the drugs industry has had lethal effects. Colombia is now the world’s largest producer of cocaine, and Mexico is rapidly becoming a global producer of heroin and fentanyl.

The rise of drugs has fostered and entrenched the region’s deep inequalities. The migration of underemployed urban youth has provided a foothold for the growth of extremely powerful drug gangs. Brazil’s Primeiro Comando da Capital now has more than 30,000 members, making it one of the largest gangs in the world, with a global reach.

Drug organizations now operate in every Latin American country and are driving homicide trends regionwide. Rather than challenging state power head-on, they seek to collude with and corrupt it. That situation, however, may be changing.

International development organizations working in the region have long lamented its “institutional weakness” and declining public trust. They call for governance reform, but nothing fundamental changes.

The principal cause of this dismal governance is inequality and a bloated bureaucracy characterized by “clientelism,” the practice of selecting or appointing people in exchange for political support.

The flip side is that professional ethics and institutional memory are virtually absent within the civil service. As a result, corruption remains pervasive in government, the police, the military, and prisons.

States in breakdown

The most salient feature of fragile governance that fosters a gradual slide toward a failed state is corruption permeating the judicial system from top to bottom, due to the penetration of drug organizations. For the urban poor, personal insecurity is an everyday reality, and for most citizens the rule of law does not exist.

When the poor are killed—by state repression, gang rivalries, street robberies, or extortion—criminal investigations are rarely launched unless relatives can afford a lawyer. Prosecution rates are minuscule, and the majority of inmates in overcrowded prisons are poor people awaiting trial.

Consequently, state capacity to counter the gradual spread of narcotics is extremely limited. This vulnerability has already produced the first examples of narco-states. In Honduras, one emerged under President Juan Orlando Hernández (in office 2014–2022). Upon leaving office in April 2022, he was extradited to the United States on charges of drug trafficking and money laundering.

Latin America’s elites attempt to justify the current economic model as providing food security and minerals to a growing world population. But they deny the violent consequences that this model produces.

Latin America’s role as a breadbasket risks morphing into one of permanent internal conflict and powerlessness.

Police officer in Ecuador: Presidencia de la República del Ecuador / Flickr [PDM 1.0])

Latin America: By fighting fire with fire, states are escalating gang violence

“Translated article from The Conversation,” by Amalendu Misra (original) (Note 1)

Gangs are a permanent presence in Latin America. They have existed as brokers of power, illicit economic actors, and spoilers in the development of several countries. Yet despite their power and influence, they were long viewed as ever-present but not strong enough to rock the boat—an irritant rather than a major threat.

Today, however, we are seeing a very different picture. Criminal organizations have become formidable forces. From island nations like Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago to economic powerhouses like Brazil and Mexico, the gang threat is rapidly spreading.

In some cases, gangs are challenging the very existence of governments in the region. Criminal groups in Haiti toppled the government in early 2024 and demanded ransoms. And in Ecuador, once praised as one of the safest countries in Latin America, a life-or-death struggle is underway against gangs that are rapidly eroding state power.

Gangs are a grave problem in Latin America, damaging the region’s economic performance. According to an IMF study, if crime levels in Latin America were reduced to the global average, the region’s annual economic growth rate would be 0.5 percentage points higher—about one-third of Latin America’s growth between 2017 and 2019.

Criminal organizations in Latin America have long been underestimated. No more. As concerns about crime-related violence rise and trust in the police declines, governments across Latin America and the Caribbean have declared states of emergency and implemented policies that would not normally be permitted, in the name of keeping people safe.

Colloquially known as “mano dura” (Spanish for “firm hand” or “iron fist”), this approach suspends basic civil rights by granting the military and law enforcement authority to arrest, imprison, and deport individuals found to have links with criminal groups. It also denies arrestees access to legal mechanisms that establish the right to a fair and open trial.

Spreading authoritarianism

The mano dura regime was introduced in Latin America by El Salvador’s charismatic president, Nayib Bukele, in March 2022. Following a surge in gang violence that left 87 dead in a single weekend, Bukele curtailed rights such as being informed of the reason for arrest and accessing a lawyer when detained.

By February 2024, more than 76,000 people—nearly 2% of El Salvador’s population—had been detained under mano dura provisions. Some criticize the crackdown as a severe human rights violation. The military has swept up people for having tattoos or living in poor neighborhoods, and thousands of innocent people have been detained in El Salvador’s overcrowded prisons.

President Bukele of El Salvador (Photo: Casa Presidencial El Salvador / Flickr [CC0 1.0])

Rather than taking steps to prevent arbitrary arrests, Bukele has openly backed the security forces. And after his party passed reforms in 2021 that gave the Supreme Court the power to dismiss and force the retirement of judges, there are now few independent judges left in the country.

Nevertheless, many Salvadorans have readily accepted the crackdown.

Thanks to Bukele’s tough stance on gangs and organized crime, El Salvador has gone from one of the most homicidal countries in the world to one of the safest in Latin America. In February 2024, amid surging approval ratings, Bukele was reelected in a landslide.

Mano dura politics are being rapidly embraced across the region. In late April 2024, Ecuadorians voted in a referendum to continue the state of emergency. This move gives President Daniel Noboa the authority to deploy soldiers to the streets to fight “drug-fueled violence” and to deport criminals.

It is rare for citizens of democratic states to voluntarily demand authoritarian measures from their governments. A recent example came in 2018, when large-scale protests erupted across Latin America. These protests helped increase the number of people who believe authoritarian rule is necessary to maintain law and order.

Similarly, support for the mano dura interventions now spreading across Latin America stems from two interrelated factors: people in distress have reached their limits, and there is a perception that only extreme authoritarian measures can address the challenges posed by gangs.

In many Latin American states, gang violence has undermined the capacity—let alone the will—of governing institutions to uphold their foundational values. Given this backdrop, it is unsurprising that fighting fire with fire is gaining approval as a means to constrain the power and influence of criminal organizations.

It is too soon to predict whether other Latin American countries struggling with gang threats will fully replicate the Salvadoran or Ecuadorian models. However, even countries with very low homicide rates, such as Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile, are now adopting some form of mano dura policy.

The “Bukele model” is gaining traction and will likely become the mainstream policy option in this violent region.

Note 1: This article is a translation of In the face of severe challenges, democracy is under stress – but still supported – across Latin America and the Caribbean by Noam Lupu, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, and Luke Plutowski at The Conversation. We would like to thank The Conversation and Lupu, Zechmeister, and Plutowski for providing the article.

Note 2: This article is a translation of Deep-seated inequality is fuelling an escalation of violence across Latin America by Andrew Nickson at The Conversation. We would like to thank The Conversation and Nickson for providing the article.

Note 3: This article is a translation of Latin America: several countries look to combat gang violence by fighting fire with fire by Amalendu Misra at The Conversation. We would like to thank The Conversation and Misra for providing the article.

Writers: Noam Lupu, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, Luke Plutowski, Andrew Nickson, Amalendu Misra

Translator: Ayane Ishida

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks