Right now, East Africa is experiencing a drought said to be the worst in 40 years. The reason is that in this region, which has two rainy seasons each year, there has been insufficient rainfall for four consecutive seasons. As a result, many people in East Africa are suffering from food shortages, and a severe famine is about to occur. The scale of the damage is considerable: in just three countries—Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia—more than 20 million people were facing acute food insecurity as of July 2022.

However, this is not a newly discovered problem. As early as January 2022, the United Nations had announced that East Africa was facing its worst drought in 40 years, and since then UN agencies have repeatedly issued warnings. While it may be difficult to prevent one of the causes—drought—properly preparing and taking action before the situation escalated into famine could have averted its occurrence. But for such measures to be taken, the grave situation on the ground must be known and judged important around the world—in other words, it must be reported. So how much has Japan reported on this East African emergency? In this article, we will look into the current situation in East Africa and also consider the volume of coverage in Japan.

Mothers and children being screened for malnutrition (Ethiopia) (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Famine and the impact in East Africa

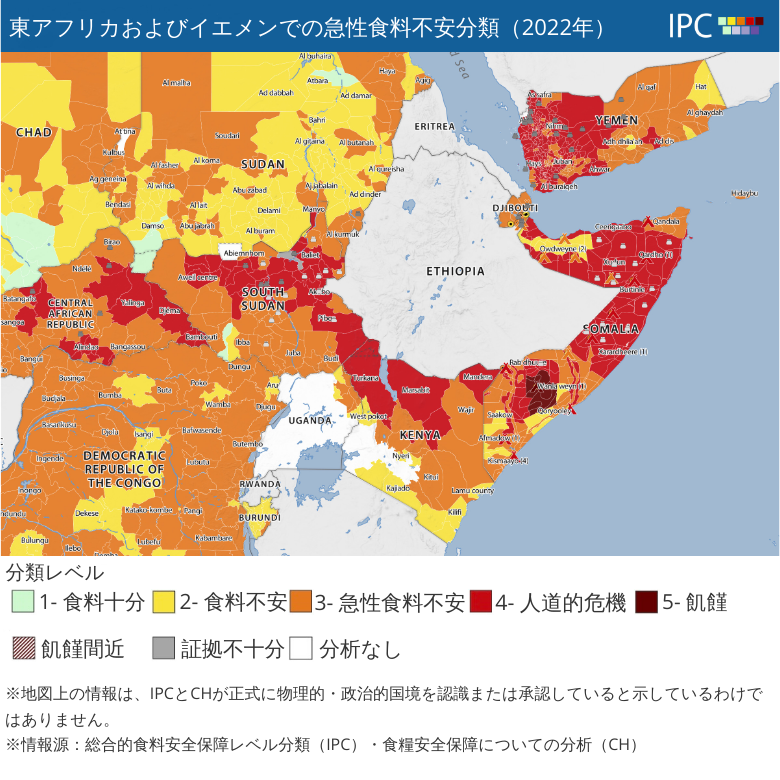

How serious is the situation in East Africa? The figure below is a map of acute food insecurity published by the system known as the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), created through the collaboration of 15 international organizations. Areas are color-coded by how imminent the food crisis is. The most severe status is “Famine (IPC Phase 5),” followed by “Humanitarian Emergency (IPC Phase 4),” “Acute Food Insecurity (IPC Phase 3),” “Stressed (IPC Phase 2),” and “Minimal (IPC Phase 1),” for a total of five phases (※1). Note that some areas are in the midst of large-scale hunger but, for various reasons, have not been sufficiently analyzed; Ethiopia is one example categorized as such.

IPC acute food insecurity classifications for East Africa and Yemen (original in English, translated by GNV)

Let us look at what “famine” means here. Above, we stated that famine is “about to occur” in parts of East Africa, but in fact the word famine has several definitions, and for a situation to be recognized as “Famine (IPC Phase 5)” under the IPC, three conditions must be met. First, at least 30% of children are identified as severely malnourished. Second, at least 2 out of every 10,000 people die per day due to clear starvation or the interaction of malnutrition and disease. Third, more than one-fifth of households face extreme food shortages. At present, there are no regions in the world officially classified as in famine. However, many regions in East Africa and elsewhere on the continent are classified one step short of famine as in “Humanitarian Emergency,” or one step before that as in “Acute Food Insecurity.” In parts of Somalia, famine is expected to be declared within 2022.

So how large is the scale of the damage in Africa facing such a crisis? Mortality statistics have not yet been compiled, but as noted above, in just the three hardest-hit countries in East Africa—Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia—more than 20 million people are said to be facing severe food shortages, and more than 23 million people are suffering from water shortages. In addition, more than 3 million head of livestock have died. And because of the shortages of food, water, and other resources, more than 1.7 million people have been displaced from their homes.

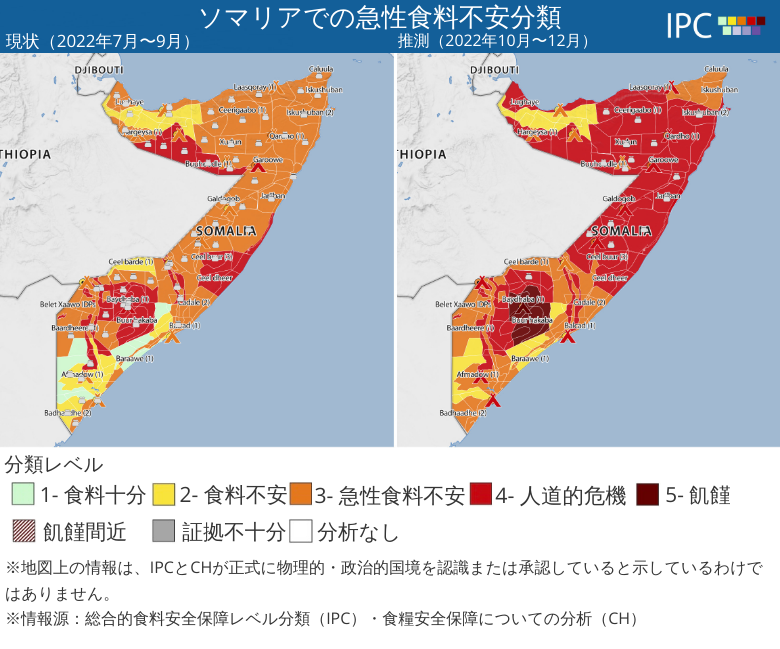

Next, we look specifically at Somalia and Kenya, the two countries particularly affected by the drought. Located in what is known as the Horn of Africa, Somalia is the most affected country in East Africa. As of October 2022, more than 7 million people nationwide were in a state of hunger. Some 386,000 children are on the brink of death, and since August, one child per minute has been admitted to health facilities for acute malnutrition. In addition to the drought, political and public health systems are fragile and unstable, there is ongoing armed conflict, and the impacts of diseases such as COVID-19 and cholera are severe. As a result, the humanitarian crisis is greatly expanding, and some areas are just shy of being declared in famine.

IPC acute food insecurity classifications in Somalia (original in English, translated by GNV)

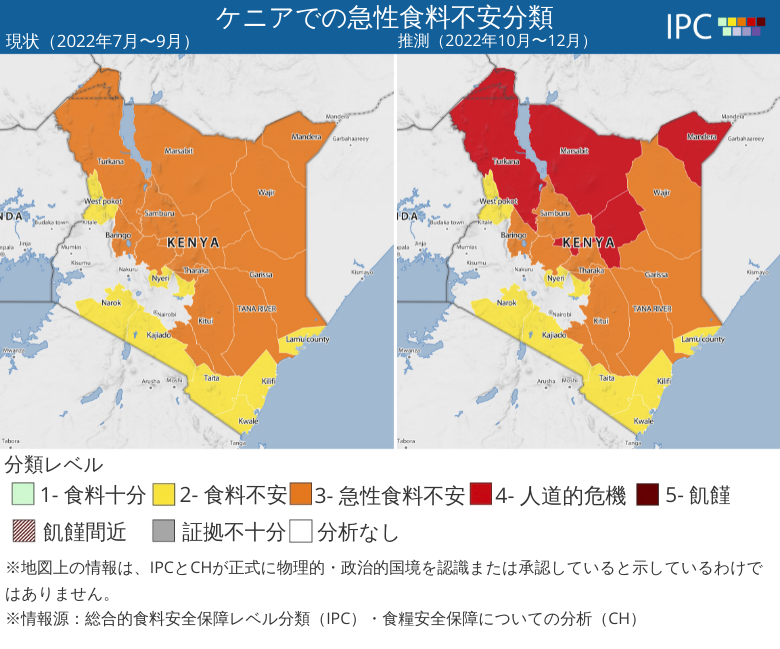

Neighboring Kenya is also heavily affected. As of August 2022, 3.5 million people in the particularly impoverished northern regions were facing a humanitarian crisis due to successive droughts, and across Kenya 1.1 million people were said to be food insecure. Kenya has established an initiative called the National Drought Emergency Fund to prepare for recurring droughts, a mechanism that allows for stable financing. However, because the scale of this drought is unprecedented in recent years, the funds raised are far short of what is needed, and the country has suffered major damage.

IPC acute food insecurity classifications in Kenya (original in English, translated by GNV)

Moreover, this is not the first time that large-scale droughts and associated famines have occurred. Somalia has experienced three famines in the past decade or so. The 2011 famine in particular was comparable in scale to the current situation, and more than 250,000 people across the country are believed to have died. The majority were children, who are less able to withstand food shortages than adults. Additionally, half of the deaths occurred before famine was officially declared.

Through past famines, the world should have learned that it is too late to wait for an official famine declaration before responding to drought and preventing the spread of hunger; early action is necessary. However, it is hard to say that such lessons are being applied in this drought. In fact, alarms were already being sounded about this hunger crisis in mid-2020.

Causes of the hunger

There are several reasons for this large-scale hunger. The biggest cause is the drought. As mentioned at the outset, East Africa has had insufficient rainfall for four consecutive rainy seasons. Moreover, temperatures are higher than usual, evaporating even the limited moisture stored in the soil. This region is prone to droughts to begin with, and there was a major drought as recently as 2016–2017; the region had not fully recovered from that event when further damage hit an already weakened environment.

Rainfall, a major factor in drought, has been declining over decades due to climate change, and recent La Niña conditions (※2) are said to have compounded the situation. Rising temperatures from global warming are also thought to be having a major impact. That said, some argue that anthropogenic climate change alone cannot fully explain these droughts. Even if climate change is one direct cause of the drought, the primary drivers are not local but stem from the activities of high-income countries. The three countries of Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia account for only 0.1% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which contribute to climate change. In other words, they are bearing the costs of other countries’ CO2 emissions.

Another major problem caused by drought is food shortages. First, reduced rainfall has led to a lack of water, crops have withered, and harvests are insufficient. Moreover, even pastoralism—which has traditionally been a crucial livelihood and asset for many in this region, adapted to its harsh dry climate—has stopped functioning well as so many animals have died.

Somalis transporting water using livestock (Photo: Water Alternatives Photos / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In addition to drought, rising food prices driven by a variety of factors—including the widening gap between rich and poor worldwide, declining yields and soaring energy prices, and two years of COVID-19—have dealt a heavy blow. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine piled on. In Somalia in particular, since regional conflict in 1990, 60% of the food supply has relied on imports, and for wheat, over 90% came from these two countries.

Other factors include domestic political situations and conflicts that leave countries with little capacity to respond to food insecurity, worsening the hunger. As noted above, in Somalia the armed group al-Shabaab is destabilizing the country and beyond. In Kenya, there were voices during the August 2022 presidential election saying that people affected by the drought had difficulty getting to the polls and, because their votes were hard to capture, there was little political attention paid to resolving the drought or providing assistance there.

Responses to hunger

How should responses to such hunger be carried out? As a premise, drought does not automatically lead to famine. If drought-resilient food systems and infrastructure are put in place before the situation worsens, and if, when domestic capacity to cope is exceeded, financial and food assistance from abroad can be effectively utilized, deterioration can be prevented. In fact, during past East African droughts, there are examples where famine occurred in Somalia, but Ethiopia weathered the crisis without large numbers of deaths.

For nations and communities to withstand drought, their own resilience is extremely important. Resilience refers to the capacity to respond to risks such as drought. Building cross-border, resilient food systems is vital to achieving resilience, and requires comprehensive reforms of agricultural practices, infrastructure development, and sufficient autonomy to implement policy. Such durable systems can bring stability amid recurrent droughts.

Drought-tolerant maize under development in Kenya (Photo: International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

However, food systems and infrastructure capable of withstanding a drought of this magnitude were not in place. Low-income countries such as Somalia and Kenya lack the resources to carry out such reforms domestically, so financial assistance from abroad is necessary—but it is hard to say that enough has been provided. Furthermore, as noted above, high-income countries bear much of the responsibility for the climate change that may be a cause of the drought, so it is all the more pointed out that they should proactively provide “support” as a form of compensation for loss and damage there.

And since sufficient preventive measures were not taken in advance, emergency assistance is now needed, yet support from abroad after the crisis has erupted is also insufficient. UN appeals for emergency assistance for the crisis in East Africa are significantly underfunded; as of November 5, 2022, the funding achieved was 56% for Somalia and 65% for Kenya. Of the total funds already raised, the Government of Japan accounts for only 0.9% of contributions to Somalia and 0.4% to Kenya.

In order to strengthen the support needed for countries to build resilience before crises occur and to bolster international aid after crises erupt, sustained attention is essential. To achieve this, the power of the media is indispensable. Reporting has the power to raise issues with the public, and differences in coverage are said to lead to differences in public awareness. This, in turn, translates into differences in governmental humanitarian assistance—because public awareness becomes pressure on governments and prompts them to act.

Coverage of the drought and hunger

So how much has this emergency in East Africa been covered in Japan? We examined Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun over the ten months from January 1 to October 31, 2022 (※3). As noted at the beginning, the East African drought is of a scale said to be the worst in 40 years, and the hunger crisis is among the worst in the world, yet there were only five articles across the three papers in ten months that focused on this as the main topic. By early 2022 it was already foreseeable that the situation would worsen, and warnings were repeatedly issued thereafter. However, none of the newspapers tracked the expanding damage; the issue was only briefly mentioned in a sentence within articles on other topics.

Let us look at coverage by newspaper. Asahi Shimbun published two articles with drought in Africa as the main topic. The first was the April 28 piece, “(From the world 2022) Two years of drought; northern Kenya goes hungry; government declares a ‘national disaster’,” and the second was the May 18 piece, “(Reporter’s note) African drought: climate change is not someone else’s problem – Yuji Endo.” After May 18, there were no further articles about drought in Africa. During the same period, there were 14 articles that only mentioned the issue in passing. For example, in the article on May 20, while discussing agricultural damage suffered by Ukrainians due to Russia’s invasion, it merely included a vague line that food price spikes caused by the invasion had worsened the food crisis in Africa.

Ethiopian women and their children waiting under a tree for medical screening (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Mainichi Shimbun published only one article with drought in Africa as the main topic, the February 10 piece “Drought in Africa: over 13 million at risk of hunger.” However, this was a reprint of a Kyodo News article. It may have been judged a problem worth mentioning but not worth dispatching correspondents for. There were 15 articles that only mentioned the issue in passing. For example, in the article on August 30, in an editorial written on the occasion of the Tokyo International Conference on African Development hosted by the Japanese government, it stated that Africa was experiencing hunger due to drought caused by climate change, but only mentioned it in a single sentence.

Yomiuri Shimbun published two articles with hunger in Africa as the main topic. The first was the June 22 piece “Food price surge adds pressure; South Sudan refugee camp; Africa; moves to restrict exports,” and the second, also on June 22, was “87,000 in South Sudan ‘starving’; ripple effects of Russia’s invasion.” There were 18 articles that only mentioned the issue in passing. For example, in the article on September 21, within coverage of the UN Secretary-General’s General Debate speech about global climate change and the food crisis, it stated that severe drought was occurring in Africa, but there were no concrete figures or descriptions conveying the severity of the situation.

Thus, each of the three newspapers wrote one or two articles focused on drought or hunger in Africa and thereafter only mentioned it vaguely. Not a single report tracked the steadily worsening situation after June, when each paper published its feature article.

Next, let us look in detail at the breakdown of coverage on the East African crisis. Here, articles that mentioned East Africa were categorized by their main topic. As a result, the most common main topic in articles that touched on this issue was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with a total of 13.5 articles (※4). The number is high even counting only articles where Russia or Ukraine appeared in the headline; it increases further in cases where the crisis in Africa was mentioned within articles on other themes. In fact, 75% of the articles that mentioned the African crisis included references to this conflict. In practice, the second most common main topic, articles on the global food crisis, often discussed it together with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; all 11 articles (※4) with the food crisis as the main topic included mention of the Russia–Ukraine war. There were also 9.5 articles (※4) mentioning the topic within Africa-related articles, and 6 articles (※4) mentioning it within climate change coverage.

As discussed so far, the drought in East Africa is on the verge of triggering famine and is likely the most severe situation in the world. However, droughts are also occurring in other parts of the world.

Looking at the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), in 2022 there were 11 countries (※5) with areas at Phase 4, “Humanitarian Emergency,” and as many as 36 with areas at Phase 3, “Acute Food Insecurity.” All of these countries are in Africa, Central/West Asia, or Latin America and the Caribbean, and 31 of them are in Africa. The IPC publishes classifications when food insecurity affects more than 20% of a country’s population. During the same period, droughts were reported in Europe, the United States, China, and elsewhere, but in none of those places did the affected population reach 20%, so no phase classification was issued and large-scale famine was considered unlikely.

So how much do Japanese media cover droughts around the world? As before, we examined Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun over the ten months from January 1 to October 31, 2022 (※6).

As a result, the number of articles with drought as the main topic was just 16 in total—very small overall. Among them, Africa’s drought is by far the largest in scale, with serious numbers of people affected, yet as the graph below shows, it was covered less than droughts in regions such as Asia or Europe and only about as much as North America.

Looking more closely at the data, among articles with drought as the main topic, all articles about Asia were about China. In Asia, Afghanistan and Yemen are on par with Africa in drought scale, with famine occurring and some areas at IPC Phase 4, “Humanitarian Emergency,” yet there were no feature articles about them at all; they were only mentioned within articles on other topics (※7).

Closing the gaps in coverage

As shown, in Japan the current situation in East Africa is barely being reported. Why is that? One reason lies in the nature of both hunger as an issue and news reporting. Hunger worsens slowly over long periods of time. News reporting, however, tends to place high value on sudden events and novelty of information there. As a result, issues like hunger are harder to feature as news.

Even within the limited reporting on drought and hunger, there are regional imbalances. Why? Because media tend to focus on high-income people and countries. In reporting, low-income countries—where hunger frequently occurs—receive little attention. At present, coverage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is excessive, and reporting on low-income countries, already limited, has shrunk further. Large-scale food crises in Africa were also often mentioned only within coverage of the Russia–Ukraine war.

In this way, disparities in coverage arise from several factors, and it is hard to say that human lives are being weighed in reporting. One background factor in drought leading to hunger and escalating into famine is the lack of reporting on the issue. As noted above, reporting has the power to raise issues with the public, and this translates into governmental humanitarian assistance. The paucity of support from the Japanese government for East Africa’s drought is likely not unrelated to the lack of coverage in Japan. Instead of focusing only on high-income countries or repeatedly covering the same issues, we also need to pay attention to regions where, if we avert our eyes, many lives will be lost.

Somalia is now on the verge of being formally declared in famine. If and when famine is declared, will Japanese media and the Japanese government finally take action?

※1 While new information is updated daily, the map displays projections for October–December 2022, so it does not exactly match the current situation.

※2 The La Niña phenomenon is when sea-surface temperatures remain below normal from near the International Date Line across the equatorial Pacific to the coast of South America.

※3 We searched the databases of Mainichi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Asahi Shimbun for アフリカ AND ( 飢餓 OR 飢饉 OR 干魃 OR 旱魃 OR 干ばつ ) (period: January 1–October 31, 2022), then categorized the results by context. Items spanning two categories were counted as 0.5 each; identical texts were counted once. Items that appeared in the search but did not address drought/hunger in Africa were excluded.

※4 As in the coverage analysis, articles spanning two main topics were counted as 0.5 each.

※5 Countries with areas at Phase 4, “Humanitarian Emergency”: Afghanistan, Angola, Yemen, Kenya, Somalia, Central African Republic, Nigeria, Niger, Haiti, Burkina Faso, South Sudan.

※6 We searched the databases of Mainichi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Asahi Shimbun for 干ばつ (period: January 1–October 31, 2022), and categorized feature articles on drought by the region they covered. Items spanning two categories were counted as 0.5 each; identical texts were counted once; mentions in passing were not counted.

※7 Looking only at mentions in passing, many articles referred to Afghanistan or North America: 12 articles mentioned drought in Afghanistan and 7 mentioned drought in North America. Reasons for mentions of Afghanistan include heightened attention after the Taliban seized power in 2021 and the Afghanistan earthquake on June 22, 2022, within the study period.

Writer: Yuna Nakahigashi

アフリカの干ばつ問題、本当に報道されてないのがよく分かりますね、気づかせてくれてありがとうございます。

一点だけ、ロシアのウクライナ侵攻?確かにそこら辺のマスコミはこの言い回し大好きですけど、GNVさんもそう捉えてらっしゃるんですかね、あるいはそうでも書かないと検閲されるのか、、