In Eritrea, located in the Horn of Africa, national elections have not been held for about 30 years. Furthermore, in the World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, it ranked last at the time of writing, below North Korea. The country faces various problems not only domestically but also in its foreign relations. What exactly is happening in Eritrea now?

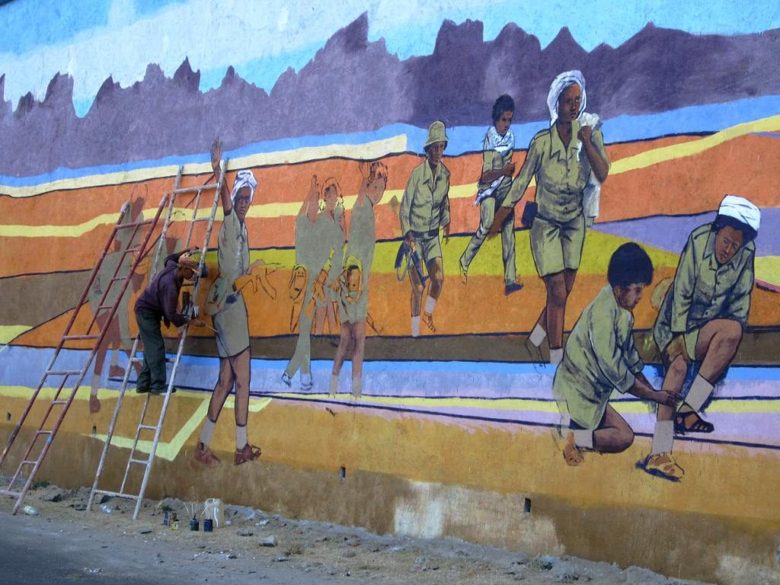

A mural painted to commemorate Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia (David Stanley / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

目次

Eritrea’s independence

Around the 10th century BCE, a Sabaean-speaking group living in the region around present-day Yemen migrated to the area near what is now Eritrea. They later absorbed Cushitic peoples and founded the Kingdom of Aksum. The kingdom prospered until around the 6th century CE, but gradually declined due to pressure from surrounding states, coming under Ottoman rule around the 16th century and Egyptian control around the 19th century. When Egyptian power waned, Italy advanced into the region and declared the colonization of Eritrea in 1890. This colonial rule lasted 50 years, but during World War II, Italy withdrew from Eritrea after a British assault in 1941, and British administration began.

After World War II, the fate of British Military Administration Eritrea became an issue at the UN General Assembly. In 1949, the British government announced an estimate that 75% of Eritreans supported independence, but due to oil interests and related strategy, the United States strongly supported union with its ally Ethiopia. As a result, in the 1950 UN General Assembly, union with Ethiopia was decided. In 1952, Eritrea entered into a federation with Ethiopia as an autonomous state and obtained its own parliament. However, Ethiopia banned political parties in 1955 and restricted Eritrea’s autonomy, imposing a repressive political system. Then, in 1962, the Eritrean parliament was dissolved by Ethiopian forces, and Eritrea was annexed as Ethiopia’s 14th province.

In this context, Eritreans exiled in Cairo, Egypt, founded the guerrilla group the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) in 1958, launching an armed struggle in Eritrea from 1961. The ELF later split into multiple groups along lines of political ideology, religion (※1), and region of origin. Among the splinter groups, the most powerful became the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), established in 1973. Under the leadership of Isaias Afwerki, now Eritrea’s president, the group expanded its influence.

The Eritrean imperial palace erected by the Egyptian government in 1872. Parts were destroyed during the independence war. (David Stanley / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Meanwhile in Ethiopia, a rebel coalition, the 1974-era Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), intensified its military campaign to topple the military regime. Sharing the goal of overthrowing the Ethiopian government, the EPRDF formed an alliance with the EPLF. The EPLF and EPRDF then fought together to defeat the military regime led by Mengistu Haile Mariam. After more than 30 years of fighting, the military regime finally collapsed and the EPRDF established a new Ethiopian government. In 1991, the ELPF declared the establishment of a provisional government, effectively making Eritrea a de facto independent state. Eritrea then formally achieved independence from Ethiopia through a referendum in 1993 April.

The president’s authoritarian rule

In May 1993, Isaias Afwerki, the leader of the EPLF, was elected president of Eritrea by the Provisional National Assembly. In his inaugural speech, President Isaias promised democracy and respect for the rule of law. However, after the EPLF was renamed as a political party in 1994, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), the president also served as party head and military commander, gradually centralizing power and establishing an authoritarian, centralized system. The only political party allowed to operate domestically is the PFDJ, forcing opposition forces to conduct their political activities abroad. In September 2001, it seemed possible that reform might arise from within the regime when 15 members of the PFDJ demanded the holding of elections and the implementation of the constitution, but 11 of the 15 were detained.

Eritrea has neither a functioning electoral system nor an implemented constitution. As a temporary measure until the constitution was adopted, a provisional national assembly was established in 1994, and after a constitution was enacted, members of parliament were to be elected by popular vote. However, although a constitution adopting democratic principles was enacted in 1997, it has not been implemented. In addition, although elections for the provisional parliament were announced for 2001, they were postponed indefinitely. Furthermore, the presidential election planned for 1997 was never held, and there have been no national elections since the 1993 referendum, allowing President Isaias to retain power.

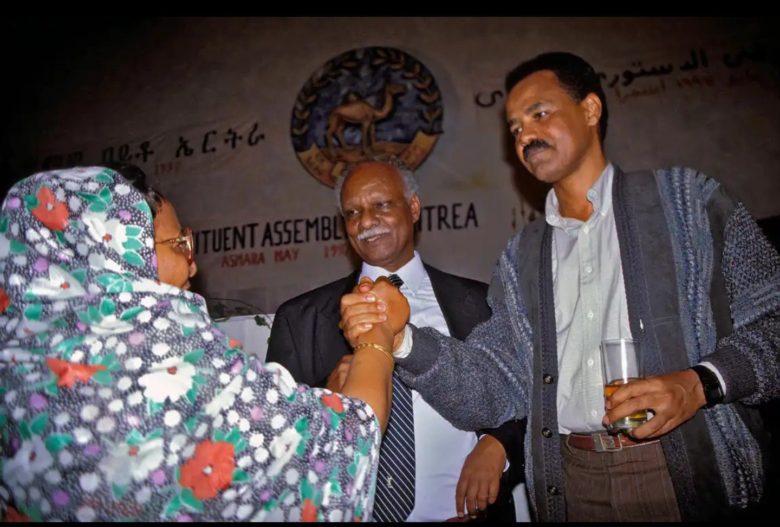

At a party celebrating the ratification of the 1997 constitution. President Isaias is on the far right. (Hebheb321 / Wikimedia Commons/ [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Although the constitution guarantees freedom of expression, free speech is not permitted in practice. For example, private media operations have been banned since 2001, and that year 11 journalists who criticized the government were arrested and detained without trial. As of 2021, these 11 journalists still had not been released, and at least four are known to have died in detention. Consequently, as noted above, in the World Press Freedom Index published annually by Reporters Without Borders, Eritrea ranked last as of 2021.

Eritreans have been deprived not only of freedom of expression but also of freedom of occupation. Eritrea has compulsory national service, and all people from 16 years old up to older ages, regardless of gender, are subject to it. It is virtually impossible for young people subject to conscription to avoid service. Every year, thousands of final-year students in secondary education (※2) are forcibly taken to a military training center called Sawa. The training lasts 1 year and includes classroom instruction in addition to military training, but corporal punishment and forced labor are tolerated, and students are reportedly treated like slaves. Based on written exam results during the training period and other factors, it is decided whether, after graduating from secondary school, they are conscripted directly into the army or continue into vocational programs or further education (in which case the major and subsequent path are designated by the government). Some students drop out of secondary school to avoid service, but if the government discovers they are not attending school, they are conscripted directly. By law, national service and work on state-run projects (※3) are supposed to last 18 months, but in practice it is often indefinite.

To escape such conscription, government repression, and poverty, large numbers of Eritreans become refugees and head abroad. As of 2018, the cumulative number of refugees who had left Eritrea exceeded 500,000. Many Eritrean refugees who fled to Ethiopia travel from Sudan to Libya, aiming to reach Europe. As of 2015, one-third of all refugees heading to Europe were from Eritrea.

Eritrean soldiers marching in a parade (Temesgen Woldezion / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.5])

Confrontation with Ethiopia

Because the new Ethiopian government established in 1991 was led by the EPRDF, which had allied with the EPLF under President Isaias, relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia were initially amicable. However, relations deteriorated due to trade issues and the use by landlocked Ethiopia of Eritrea’s Red Sea ports. The Badme area along the Eritrea–Ethiopia border had not been clearly demarcated since Eritrea’s Italian colonial period. As a result, although effectively under Ethiopian control, the two countries held differing views on the border in the Badme area. Tensions rose, and in May 1998 clashes broke out in Badme between Eritrean and Ethiopian forces, with Eritrean forces continuing attacks using tanks and other weapons. The cycle of attack and counterattack escalated into a large-scale war. This war was among the most devastating border wars in Africa, with an estimated 80,000 deaths over two years.

In 2000, Eritrea and Ethiopia discussed the border issue at a conference led by Algeria and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and concluded the Algiers Peace Agreement. The neutral Ethiopia–Eritrea Boundary Commission (EEBC) (※4) was established, and both countries agreed to accept the border as determined by the EEBC to end the dispute. The UN peacekeeping force UNMEE (United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea) was deployed to monitor the ceasefire and remained until 2008. Despite the peace agreement, the border issue did not improve. Although the EEBC’s final ruling in 2002 awarded the disputed Badme area to Eritrea, Ethiopia rejected the decision and continued its de facto control by stationing its troops there. In response, Eritrea refused negotiations until the EEBC ruling was implemented, leading to repeated clashes along the border, including a 2016 confrontation that left hundreds dead.

The Ethiopia–Eritrea conflict also affected other countries. In Somalia, a neighboring state of both, the Somalia conflict broke out in 1991, and a coalition known as the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) was formed in 2000 based on Islamic law. The ICU armed itself while gaining support from many civilians, even temporarily unifying southern Somalia. However, viewing the ICU as a threat, Ethiopia invaded Somalia to overthrow it, and the ICU was dissolved in December 2006. Subsequently, a radical youth faction from the ICU withdrew from Somali cities, formed Al-Shabaab with the goal of establishing an Islamic state in Somalia, and began guerrilla attacks against Ethiopian forces. Eritrea, seeking to weaken its common enemy Ethiopia, is said to have provided Al‑Shabaab with weapons and funds, meaning Eritrea and Ethiopia were indirectly at odds in the Somalia conflict as well. Regarding Eritrea’s support for Al‑Shabaab, the UN Security Council imposed sanctions in 2009.

Beyond Ethiopia, Eritrea has also seen relations deteriorate and has clashed with other Horn of Africa countries. With Djibouti, it was in a state of war over their border for about ten years. A peace agreement was concluded in September 2018, and relations have since been restored. Eritrea also clashed with Sudan over the Eritrean opposition group EIJM (Eritrean Islamic Jihad Movement) based in Sudan, leading to a break in diplomatic relations from 1994, but a peace agreement was concluded in 2000, and relations with Sudan have since normalized.

International relations with the Middle East

Eritrea has also influenced the Yemen conflict. The conflict broadly began as a confrontation between the Yemeni government and the Houthi movement, and by 2014 the Houthis had seized the capital. Neighboring states, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), launched airstrikes and deployed ground forces, intervening militarily to support the effectively non-functioning government. Meanwhile, Iran and the Lebanon-based organization Hezbollah are said to support the Houthis. In this way, the Yemen conflict expanded into a regional conflict.

Eritrea, which previously disputed Yemen over the Hanish Islands territorial issue, initially supported the Houthis but later reversed its stance and sought to build friendly relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In 2015, it concluded a contract to lease Eritrea’s Assab port to Saudi Arabia for 30 years. Eritrea also permitted the UAE to build a military base at Assab port as an operational hub for attacks against the Houthis. Behind this move was Eritrea’s intent to cultivate good relations with influential countries like Saudi Arabia and secure their support in diplomacy. In addition, Eritrea’s approach to the UAE was likely facilitated by the deterioration of relations between Djibouti—then disputing its border with Eritrea—and the UAE.

Reconciliation with Ethiopia

As noted above, Eritrea and Ethiopia continued to be at odds even after the 2000 Algiers Peace Agreement, but a turning point came when Abiy Ahmed became Ethiopia’s prime minister in 2018. From the moment he took office, Abiy moved to restore relations with Eritrea. With cooperation from the UAE, a peace agreement was concluded with Eritrea in 2018, ending nearly 20 years of hostility. The border was temporarily opened. Trade picked up between Ethiopian and Eritrean traders, and separated families—including those who had fled as refugees and those who remained—were reunited. However, this situation did not last; the border was closed again after a few months, and free crossings ceased. One factor behind this closure was likely that the border opening led many Eritreans to cross into Ethiopia as refugees, and the Eritrean government feared an accelerating exodus.

Scene in a refugee camp in Ethiopia (EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Although relations with the Ethiopian government improved, a new conflict later erupted. In 2020, war broke out between the Ethiopian government and the northern Tigray region, and Eritrea intervened militarily. Since 1991, when the EPRDF established a new regime, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) had been a central part of the Ethiopian government, with its leader becoming the first prime minister, and had long led the central government. Although the TPLF ceased to lead the central government when Abiy became prime minister in 2018, it retained control of regional governance in Tigray. It opposed Abiy’s decision to cancel regional elections due to the spread of COVID-19 and unilaterally held its own election in September 2020. The TPLF won by a landslide, but the federal government refused to recognize its legality, intensifying the confrontation. In November 2020, the TPLF attacked a federal military base, and the federal army and reinforcements from other regions intervened, escalating into war. Eritrea intervened in support of the Ethiopian federal forces. Within half a year, 200,000 Tigrayans fled to Sudan as refugees.

Why did Eritrea intervene in the Tigray conflict? Several reasons have been suggested. First, during the period of Eritrea’s border dispute with Ethiopia, the TPLF, which held power in Ethiopia, had long been treated as an enemy by Eritrea. Second, Eritrea sought to boost its influence in the region; President Isaias has previously sought to increase Eritrea’s clout through interventions in neighboring countries, and a weakened regional power like Ethiopia could, in Eritrea’s view, enhance its own profile and influence. Third, there is the possibility that Eritrea intervened to punish its own refugees who fled into Tigray. During the intervention, Eritrean forces reportedly carried out abductions, killings, and rapes of Eritrean refugees sheltering in Tigray, forcing them to make the brutal choice of moving to other camps or returning to Eritrea.

While Tigrayans and Eritrean refugees have suffered devastating harm, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy denied Eritrea’s military involvement for months. In March 2021, the prime minister finally acknowledged Eritrea’s involvement in the Tigray conflict and promised the withdrawal of Eritrean troops. Although some Eritrean forces withdrew in June 2021, there has not been a complete withdrawal, and there were reports of renewed Eritrean attacks on the TPLF in January 2022.

Eritrean refugees who fled to Ethiopia from the Tigray conflict (UNICEF Ethiopia / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

A path to improvement?

As we have seen, conditions inside Eritrea are severe. Due to intense government repression, change from within the country or the regime is difficult. However, that does not mean there are no citizens speaking out against oppressive politics. Among those who fled Eritrea, some broadcast radio programs to reach Eritreans at home, providing various information about the situation inside and outside the country. In the past, there was also a protest movement called Freedom Friday (Freedom Friday)(※5) both inside and outside Eritrea.

In foreign affairs, although the peace agreement between Eritrea and Ethiopia was achieved, it did not necessarily lead to peace in Eritrea or the surrounding region. Rather, it can be said to have been one factor behind Eritrea’s military intervention in the Tigray conflict. Moreover, by achieving peace and intervening in the conflict, Eritrea gained support from regional powers such as Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, making it unlikely that other countries will apply pressure to bring about domestic change in Eritrea. What lies ahead for Eritrea?

※1 In Eritrea, Christians and Muslims form the vast majority of the population, with each comprising about half.

※2 In this article, “secondary school” refers to both junior high and high school in the Japanese education system. Therefore, the final year of secondary school corresponds to the third year of Japanese high school.

※3 Here this refers to all public works operated by the state, such as agriculture and construction.

※4 The EEBC consists of five members: two lawyers appointed by Eritrea, two appointed by Ethiopia, and a commission chair.

※5 As a way to protest without facing government repression, people would stay at home every Friday night, creating empty streets as a form of protest.

Writer: Ayano Shiotsuki

Graphics: Yosif Ayanski

わかりやすいです