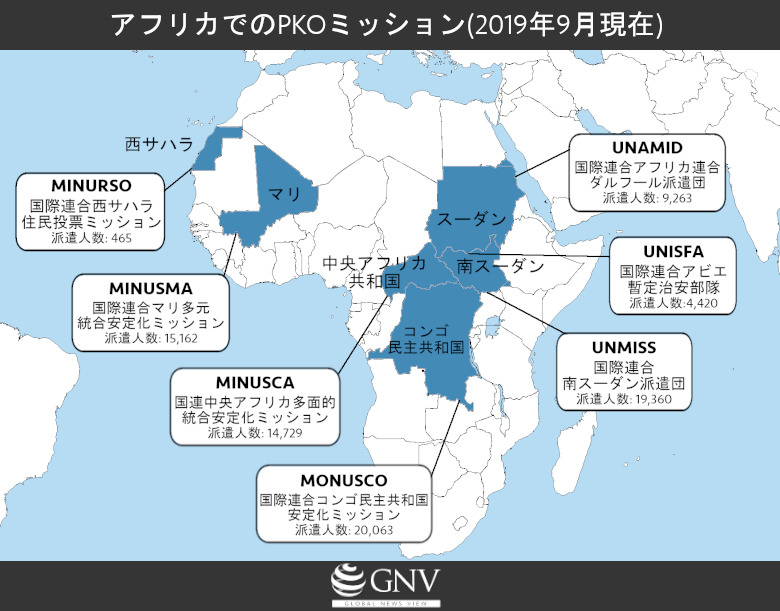

United Nations peacekeeping operations (hereinafter, PKO: Peacekeeping Operations) are known as part of the activities of the United Nations (hereinafter, the UN). In fiscal year 2019, a massive budget of about US$6.5 billion was allocated to PKO, and around 110,000 soldiers are operating around the world. Of the 13 missions currently active, more than half—seven—are being conducted in Africa.

Although PKO is often perceived as contributing to world peace, in reality it faces various problems. On November 25, 2019, protests erupted against the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) and the government forces operating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (hereinafter, the DRC), resulting in eight deaths. The PKO mission in the DRC is the largest in the world, and over the past 20 years significant human and financial resources have been invested, yet the results do not seem satisfactory to the people of the DRC. The anger of the protesters this time also stemmed from the failure of MONUSCO and the government forces to protect civilians from attacks by rebel groups. What issues underlie such cases? Let us look at the current state and challenges of UN PKO in Africa.

Pakistani PKO soldiers patrolling a road in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: MONUSCO Photos / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Overview and History of PKO Activities

First, a brief explanation of PKO. PKO are missions carried out mainly by soldiers from multiple UN member states. PKO operate largely in accordance with the three core principles. In brief: first, the deployment of forces requires the consent of the parties concerned; second, they must not take actions that support any one party to the conflict; and third, weapons are not to be used except in self-defense.

PKO began in 1948 when the UN Security Council (hereinafter, the Security Council) authorized the deployment of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) to the Middle East. These activities were limited to providing indispensable support to political efforts—such as calming situations and maintaining ceasefires—and often involved monitoring, reporting, and confidence-building. The objective of such traditional activities was to resolve situations and prevent the recurrence of conflict.

However, with the end of the Cold War, the strategic context of UN PKO changed dramatically. The East–West confrontation, which had often paralyzed the Security Council and hindered PKO deployments, ended, leading to an increase in the number and scale of PKO missions and a substantial expansion of their roles. For example, tasks included restoring security, observing and conducting elections, and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of ex-combatants. While traditional missions continued to exist, most took on broader roles than before, and the UN effectively shifted PKO from “traditional” missions centered on general monitoring by military personnel to complex “multidimensional” activities.

(Note 1) The official names of each mission are listed at the end of the article.

Africa and PKO

In 1960, PKO was first deployed to sub-Saharan Africa to stabilize the Congo Crisis, and after the Cold War, multidimensional activities were conducted across Africa, including in Liberia, Angola, Mozambique, and Namibia. However, the early 1990s were difficult years for PKO. The United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) was deployed to address the Somali conflict, but because it operated amid ongoing turmoil, clashes with militias occurred frequently, resulting in casualties and a forced withdrawal. Furthermore, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) was dispatched in 1993 following a peace agreement in the Rwandan conflict, but implementation of the agreement was poor, and when the genocide began in 1994, the mission was drastically downsized, effectively relegated to the role of bystander. Thus, the world experienced the “failures” of UN PKO, and activities stagnated in the late 1990s.

Around 2000, however, activities gradually revived, beginning with the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) and the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC)—and later its successor, MONUSCO—and continue to the present. For example, in the DRC, in addition to supporting the protection of civilians, restoration of security, disarmament of rebel groups, and development of a democratic legal system, the mission also established Radio Okapi (Radio Okapi), which has become the country’s largest media outlet, demonstrating the comprehensive nature of its activities.

Having evolved through this history into performing a wide range of tasks, where do the soldiers deployed around the world come from? Because of the number of missions being conducted, Africa is often seen as “being supported” by the world as a passive recipient of PKO. However, Africa can also be said to be “contributing” to global PKO with its troops. According to UN data as of the end of October 2019, Ethiopia ranked first worldwide in number of personnel deployed to PKO, contributing 7,026 personnel. In addition, Rwanda ranked third and Egypt seventh; 12 of the top 20 countries were African. Overall, personnel deployed to PKO from African countries accounted for about half—48.5%—of the total. Ethiopia’s increasing contribution is particularly striking: while African contributions to PKO increased by 46% between 2010 and 2015, 40% of that increase was accounted for by Ethiopia.

Behind this is the geographic proximity between African countries and the countries where PKO missions are conducted. In other words, one motivation for African countries to contribute actively to PKO is to prevent negative impacts on their own countries from instability in neighboring states. There may also be an aspect of continental solidarity. This trend grew stronger following the time when the Security Council and the deployed PKO failed to protect civilians from the genocide in Rwanda. The phrase “African solutions to African problems” came to be heard both within and outside Africa, and in 2002 the Organization of African Unity (OAU) evolved into the more comprehensive and proactive African Union (AU).

Political Challenges

Given the scale of PKO activities in Africa as described above, what problems do PKO face there? First, let us focus on political challenges—namely, problems that arise in the process of establishing missions at the UN Security Council, where decisions regarding PKO are made. At UN Headquarters in New York, far from Africa, the size and mandate of PKO are decided and resolutions to launch missions are adopted. One problem that arises is that it can take a long time from the occurrence of a situation requiring PKO deployment to the actual arrival of PKO forces. Once the Security Council authorizes a PKO deployment, countries must be found to provide the troops in accordance with the resolution. It is not uncommon for considerable time to pass during this process.

Furthermore, assembling the forces needed to execute a mission is not easy. Providing national forces to PKO entails costs and the risk of soldiers being injured or killed, so many countries hesitate to decide, and as a result, it is difficult to gather sufficient personnel—an issue in itself. In terms of funding, there are also cases where the United States, rather than providing troops based on needs, limits the numbers decided by Security Council resolutions with an eye to its own assessed contributions. As can be seen from the graph above, high-income countries, including the United States, generally provide very few troops.

The Security Council adopting a resolution (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Moreover, even amid overall shortages of personnel and funds, the human and financial resources devoted to peace operations during past crises in Europe were overwhelmingly larger, while relatively fewer have been devoted to Africa. Although not UN PKO, the Implementation Force (IFOR), deployed after the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the former Yugoslavia and launched in 1996, initially deployed about 60,000 personnel. The Kosovo Force (KFOR), responsible for maintaining security in Kosovo since 1999, initially deployed about 50,000 personnel. By contrast, the mission in the DRC—larger in terms of conflict scale when measured by area of operations and number of deaths—deployed a maximum of about 22,000 personnel. Kosovo, which has only 1/200th the area of the DRC, had more than twice as many personnel deployed. In this context of limited resources and on-the-ground needs, whether the Security Council can assign realistic and effective mandates commensurate with those needs is also a major challenge.

Challenges on the Ground

PKO do not necessarily receive the size, funding, and roles that match field needs, and they face various problems on the ground. It is not hard to imagine that insufficient personnel increases the likelihood of failing to protect civilians. As noted at the outset, the incident that occurred in the DRC at the end of November 2019 was triggered by public anger at MONUSCO and the government forces’ failure to protect. Another example is that failures in protection have been pointed out in South Sudan and the Central African Republic. However, given shortages of personnel and funds, one must concede that there are limits to protection. For example, if there are too few personnel, it becomes difficult to patrol far from bases. With limited funding, reliance tends to fall on troops from African countries where wage levels are relatively lower, which may mean training is not sufficient or soldiers have less experience. As for the motivation of the officers and soldiers of the national militaries being deployed, when fulfilling duties in a foreign land unrelated to their own country’s security rather than working for their own national security, they may become more defensive or have a relatively smaller willingness to take risks than when working for their own country.

Guatemalan special forces operating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: MONUSCO Photos / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

On the ground, there are also regions where trust in the UN is being eroded and disappointment is spreading due to actions that compromise UN impartiality. As introduced in the three core principles of PKO at the beginning, PKO are supposed not to take actions that support either party to a conflict. In reality, however, in places like the DRC and Mali they have been fighting rebel groups alongside national armies. This leads to being viewed as an enemy by rebel groups and increases the likelihood of being attacked; the mission in Mali has become the most dangerous in the world. In the DRC, repeated reports of human rights abuses by the national army have also fueled public resentment.

Furthermore, undermining trust in the UN are incidents where soldiers deployed in PKO commit crimes. UN investigations revealed that between 2014 and 2015, 41 PKO soldiers in the Central African Republic were involved in sexual abuse and exploitation. Reports indicate that women and even minors were targeted, and such abuse was committed in exchange for clothing and food. In addition, the Geneva-based research institute Small Arms Survey (Small Arms Survey) stated in its report that the UN mission in South Sudan in 2013 supplied weapons to rebel forces in the town of Bentiu. While such actions are rare and not widespread in PKO, they can greatly damage PKO’s image on the ground.

Finally, differences in language and culture also pose barriers on the ground. It is easy to imagine that not understanding the language and culture of the host country will cause some communication difficulties. However, there is a dilemma here. If more troops are deployed from neighboring countries because language and culture are easier to understand, their own national interests may become closely involved, making it harder to act impartially and neutrally. Conversely, when troops are deployed from distant countries with fewer interests at stake, impartiality and neutrality may appear to be maintained, but as noted above, limited understanding of language, culture, and customs can hinder smooth communication and affect operations.

Rwandan PKO soldier on mission in Mali (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Peace Activities Other Than UN PKO

While UN-led PKO carry out a wide range of activities in Africa amid various challenges and constraints, they are not the only actors engaged in peace activities. In recent years, the contributions of Africa’s regional organizations to peace operations have been notable. As noted earlier, this relates to the trend toward regionalization in Africa. In addition to the AU, which covers the entire continent, more geographically limited regional organizations within Africa are active, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Depending on the case, they may collaborate with PKO, act separately at the same time, or hand over and take over missions. A major PKO jointly conducted by the UN and AU is the African Union/United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), a hybrid mission of the UN and AU. UNAMID has been downsizing since 2017 due to improved conditions, but in this way Africa’s regional organizations make significant contributions to peace operations in Africa and often cooperate with PKO.

This article has examined the current state of PKO activities in Africa and the political and on-the-ground challenges involving various factors. Many countries are reluctant to engage in PKO where their own interests are not involved, and PKO operate amid a lack of political support. In such circumstances, not only do PKO often fail to fulfill their original roles, but many associated problems also arise, potentially heightening distrust of the UN. At the same time, PKO are not designed to resolve conflicts; their role is to ensure stability until political solutions are implemented. It is important to continue exploring what role PKO should play and what better forms they can take, while also ensuring global attention, funding and troop contributions, and other support flow without hindrance.

PKO soldiers involved in a mission in the Central African Republic (Photo: United Nations Photo / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Note 1: The following official names are listed in the order they appear in the article.

United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO: United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO: United Nations Truce Supervision Organization)

United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II: United Nations Operation in Somalia II)

United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR: United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda)

United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL: United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone)

United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC: United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Organization of African Unity (OAU: Organization of African Unity)

African Union (AU: African Union)

Implementation Force (IFOR: Implementation Force)

Kosovo Force (KFOR: Kosovo Force)

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States)

Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS: Economic Community of Central African States)

Southern African Development Community (SADC: Southern African Development Community)

African Union / United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID: African Union / United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur)

Writer: Natsumi Motoura

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi, Yow Shuning

PKO兵士提供にはアフリカの国々が多いとは知りませんでした。

アメリカなどの高所得国はよく戦争をしているイメージですが、実際に国連のPKOでは兵士を出さず、お金だけだすのはなんだか皮肉です。

PKOの兵士はどこから派遣されているのか気になっていたので知れてよかったです。それがアフリカからの派遣が多いのは驚きでした。

また、高所得国がニューヨークで決定を下すにも関わらず、PKOの兵士に高所得国からの派遣が少ないのは違和感を思えました。