In July 2020, construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile, which Ethiopia has been advancing, was nearing completion and impoundment began. The Blue Nile, which has its source in Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, is a tributary of the Nile and supplies 80 percent of the Nile’s flow during the rainy season. The Nile has long been a symbol of Egypt and an indispensable presence for agriculture and the economy in Northeast Africa. As the volume of water flowing downstream has decreased, Egypt and Sudan, which regard this as a matter of survival, have opposed the dam’s construction, making it a source of interstate friction and leading observers to warn that it could escalate into conflict (as noted).

Such water-related problems have increased since the 2000s and tend to be growing more serious. Behind this are factors such as global population growth and climate change. Not only in Northeast Africa but around the world, water shortages and disputes over the rights to use rivers and lakes are becoming seeds of conflict. Moreover, once conflict breaks out, water resources can be lost due to attacks, and water itself can become a “weapon” in the conflict. As the frequency and scale of water-related conflicts are expected to worsen further, are Japanese media aware of this issue and trend, and giving it sufficient attention in international reporting?

A dried-up canal, Rajasthan, India (Photo: Editor GoI Monitor/ Flickr.com [CC-BY-SA-2.0])

目次

Global water scarcity

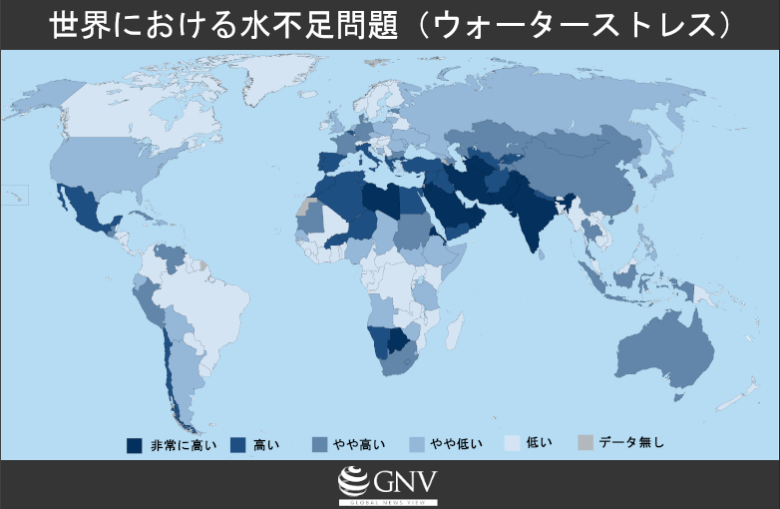

According to data from the World Resources Institute (WRI), 17 countries that are home to one-quarter of the world’s population face extremely high water stress (Note 1). Water stress refers to periods when demand for water exceeds supply, and “extremely high” indicates that agricultural, industrial, and domestic water use over a year accounts for 80% or more of available water resources. Under such conditions, if the supply of water resources becomes unstable, there is a risk those resources will be depleted. At present, agriculture is the sector that uses the most water resources. Globally, agriculture accounts for 70% of water withdrawals. For example, producing 1 kilogram of beef requires 15,400 liters of water, chicken requires 4,325 liters, and grains require 1,644 liters of water to produce. For reference, the minimum amount of water a person needs to live healthily is 50 liters. Meanwhile, over the past 50 years, with the population having grown by 4 billion, domestic water consumption has increased sixfold worldwide, while industrial and agricultural water use has tripled and doubled, respectively.

Created based on data from the World Resources Institute (Aqueduct)

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), one in three people worldwide lack access to piped water at home and instead obtain water from wells or sources such as springs, rivers, or lakes located away from their homes. In addition, about 2 billion people use drinking water contaminated by wastewater. If current trends continue, by 2025, up to half of the world’s population will be living in areas of high water stress. However, increased population and economic activity are not the only causes of water stress; climate change is also deeply involved. With rising temperatures, reduced precipitation, and worsening desertification, unprecedented droughts are being observed around the world. It is projected that arid regions will become drier and humid regions will see greater precipitation. On WRI’s indicators, among the 17 countries with extremely high water stress,12 are in the Middle East and North Africa. This region, which is home to about 7.5% of the world’s population, has only 1.4% of the world’s freshwater. In this region, where armed conflicts are concentrated, water scarcity is said to be a source of tensions and friction.

The Pacific Institute recorded a total of 676 incidents of conflicts and violent events related to water over the 20-year period from 2000 to 2019. About two-thirds of these (466 cases) occurred since 2010 onward, clearly showing the worsening problem of water resources and conflict. The region with the most incidents is West Asia (the Middle East), mainly concentrated in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria. Yemen, in particular, has the most recorded incidents, accounting for 26% (131 cases), and the situation has worsened especially since the military intervention by the Saudi-led coalition in 2015. The next most affected region is Sub-Saharan Africa, where many conflicts are linked to places such as Mali, Kenya, and Somalia. Another hotspot is South Asia, where friction between India and Pakistan stands out. Below, we introduce three patterns of the relationship between water and conflict, with case studies.

Water issues that trigger conflict

Throughout history, humans have fought over various resources, and water is no exception. Today, with population growth and global warming, water scarcity has worsened and is increasingly a cause of conflict. Causes include disputes over access to well water at the household or village level; protests over water shortages arising from pollution or inadequate water infrastructure; and, between states, disputes over rights to use water resources such as rivers and dams. Such triggers are particularly common in regions with high water stress. Here we present examples from Kenya, Syria, and Kyrgyzstan.

In Kenya’s arid northern regions, access to water often becomes a flashpoint, and in 10 incidents recorded by the Pacific Institute since 2010, about 140 people were killed. Most incidents occur between crop farmers and transhumant pastoralists. Although this conflict has been ongoing for years, it has intensified due to climate change and problems in the allocation and management of water resources. For example, amid scarcity, access to newly built water-related infrastructure and the distribution of benefits can themselves become triggers for conflict.

Syria also illustrates the link between water resources and conflict. Between 2006 and 2011, Syria suffered an unprecedented drought. By 2009, about 800,000 people had lost their jobs and food due to poor harvests, and yields of staple wheat and barley fell by 47% and 67%, respectively. Government agricultural policies and the inefficiency of surface irrigation used by many farmers exacerbated the water problems caused by the drought. As a result, by 2011 around 1.5 million people had fled from rural areas to cities and surrounding camps, and anti-government demonstrations erupted in Damascus and Aleppo in March 2011 over famine and recession caused by the drought, as well as government corruption. These protests, part of the “Arab Spring,” are considered the starting point of the Syrian conflict.

Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia is also plagued by water shortages. In rural areas of the Fergana Valley—stretching from eastern Uzbekistan into Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan—disputes over water from the Naryn and Karadarya rivers have intensified. These disputes have crossed borders and became more serious in 2018. Water from canals flows from Tajikistan to Kyrgyzstan, but when Tajikistan restricted the flow, tensions escalated into violence, including killings. Further, to resolve its own water problems, Kyrgyzstan has plans to build a dam on the Naryn River that flows into Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan has protested Kyrgyzstan’s dam plans, and there are fears of escalation into conflict.

Water resources harmed by conflict

When armed conflict occurs, water resources can be harmed directly or indirectly (whether intentionally targeted or not). For example, because water resources have strategic value during conflict, wells, treatment plants, reservoirs, and similar facilities may be targeted to cut off the enemy’s supply. Even without being targeted, large-scale bombardment can destroy water infrastructure, or pollution during conflict can render water unusable. Here we present cases from Yemen, Ukraine, and Colombia.

Yemen: Safe water (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid/Flickr.com [CC-BY-SA-2.0]

The conflict in Yemen stands out in this regard. As of 2015, more than 1.3 million people had lost access to safe water due to the conflict. Since 2015, the Pacific Institute has documented 121 incidents in which water-related facilities such as pipes and treatment plants were targeted. This accounts for about a quarter of all such incidents worldwide since 2010. Due largely to numerous airstrikes by Saudi Arabia, water systems in cities controlled by the opposing Houthi movement have been almost completely destroyed. In this situation, many civilians can only rely on private water tank trucks. However, on top of the water shortage, a gasoline shortage has caused transportation costs to skyrocket, and by 2018 some 1.93 million people could no longer afford to buy water. In addition, disruptions to piped supply have caused water shortages that triggered a public health crisis, with waterborne diseases such as cholera surging nationwide.

In eastern Ukraine, where conflict has continued since 2014, water resources have also been a problem. At its peak, about 2.3 million people temporarily lost access to safe water due to the conflict or were at risk of losing it. In the Donbas, the epicenter of the fighting, utilities such as water and power lines have become targets for the warring parties. In 2017, a water treatment plant came under sustained shelling, and utilities around Donetsk city were shut off for more than 24 hours. Because much of the Donbas’s water infrastructure was installed 70 years ago and therefore requires regular maintenance, utility workers can only perform temporary repairs during lulls in shelling, and contamination of drinking water due to system failures is becoming a matter of time.

In Colombia’s conflict, water resources have also been targeted. The conflict between government forces and paramilitaries on the one side and rebel groups on the other has dragged on for 60 years, and in 2014 rebels (FARC) attacked water channels in central Colombia, depriving about 200,000 people of access to safe water. In 2015, the water treatment plant in Algeciras was attacked twice in one week, and near the Mira River rebels bombed an oil pipeline, releasing 10,000 barrels of oil into the waterway. As a result of this pollution, about 150,000 people relying on the Mira River’s water could not access safe water for 18 days.

Water used as a weapon of war

Finally, we address cases where water is used as a weapon in conflict. This includes intentionally inducing water shortages by restricting access to water resources; polluting rivers; or causing floods by destroying dams or releasing water. The impact of such actions is enormous, affecting not only people but also the environment to a great extent. Here we present examples from Iraq and Syria; India and Pakistan; and Israel and Palestine.

The so-called Islamic State (IS), which temporarily controlled parts of Iraq and Syria, reportedly used water as a weapon on multiple occasions. As of 2016, IS controlled many major dams in Iraq and Syria, enabling it to control water resources on the Euphrates and Tigris. The group used dams to restrict water distribution to hostile rural areas on the one hand, and to release water to force evacuations downstream on the other. During the battle for Mosul, IS cut power to several pumping stations to block the Iraqi army’s advance, shutting off water to eastern Mosul. Civilians fled into IS-controlled areas to obtain water and were ultimately used by IS as human shields.

Iraq’s largest dam, the Mosul Dam (Photo: Rehman Abubakr/ [CC-BY-SA-4.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

In South Asia, water has also reportedly been used as a weapon. In the dispute over Kashmir between Pakistan and India, water resources have become a tool of confrontation. In February 2019, after a militant group said to be backed by Pakistan bombed an Indian military bus, killing 40 people, the Indian government threatened to stop the flow of the Indus River from India to Pakistan. Later in August, Pakistan accused India of using water as a weapon, claiming India unilaterally released water from a dam on an Indus tributary, causing flooding in downstream areas of Pakistan. The two governments are bound by a treaty to share Indus water resources and flow information. Pakistan argued that India’s actions violated the treaty and constituted an act of war.

Water resources are also a major issue between Israel and Palestine and have been pointed out as one of Israel’s weapons. For example, the Israeli government effectively blockades the Gaza Strip and controls the flow of goods. With maintenance of water facilities impossible under these conditions, 97% of its 2 million people lack access to safe water. In the Israeli-occupied West Bank, 294,000 people have restricted access to water. There are frequent reports of Israel refusing to install or destroying water facilities to displace Palestinians and expand Israeli settlements.

Water and conflict that go unreported

As discussed above, conflicts over water manifest in various forms, and both their number and intensity have been increasing in recent years. Moreover, such conflicts are not confined to a single region; due to climate change and other factors, available water is decreasing and the problem is global. Are Japanese media recognizing this reality and reporting on it in line with its gravity?

To explore this question, we examined and analyzed articles on water and conflict that appeared on the international pages of the Yomiuri Shimbun (Note 2) from 2010 through December 31, 2019. We found very few relevant articles. Over ten years, only 13 articles mentioned water and conflict, averaging just one or two per year. Of these 13, only two had water and conflict as the main focus; in the rest, water issues were included only as one element among several in broader conflict coverage. Given the seriousness of water conflicts, this is clearly extremely limited.

Ethiopia. People gathered around a newly built well (Photo: Julien Harneis / Flickr.com [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Next, let us view the 13 articles that mentioned water conflicts by region. First, in the Middle East and North Africa, where water stress is most severe, there were five articles over the decade. Of these, only one focused on water and conflict per se, discussing issues between Israel, Palestine, and Jordan over water levels and withdrawals from the Dead Sea and the Jordan River. Other mentions included two articles on Syria and one each on Iraq and Gaza. There were no mentions of Yemen, where the link between water and conflict is among the most severe in the world.

What about water sources and conflict in Asia? Seven articles mentioned water conflicts in this region. Among them, a short article focused on tensions between China and India over Tibetan water sources. In 2013, India protested China’s dam plans, which had been announced without prior explanation. The other articles discussed conflicts in which water issues were one element; three concerned the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. The remaining articles were about China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Vietnam. There were no mentions of Afghanistan or the Central Asian countries, where the relationship between water resources and conflict is a growing concern.

Regarding the African continent, where water problems are severe, the only mention over the ten years was an article on South Sudan (2014/6/19) containing just the sentence: “At UN facilities, displaced people are being supplied with only about one-seventh of the required amount of sanitary water.” There were no mentions related to Europe or the Americas.

Conclusion

For people living where water stress is low and supply is stable, worries such as “there isn’t enough water,” “the tap may not run tomorrow,” or “we have to fight to get water” may be hard to imagine. Yet one in three people globally suffer such realities. Warnings that “the next great war will be over water” are frequently made, but even now conflicts related to water resources are erupting in many places and increasing. If the trends introduced in this article continue, the feared emergence of even larger conflicts may not be far off. That said, this is not irreversible. With sufficient effort, water problems can be solved. But without awareness of the current situation, there will be no progress toward solutions. Judging from Japanese reporting, information on water and conflict is close to nonexistent. Addressing this information deficit may be a good place to start.

Note 1: WRI’s five water stress levels are: low, low-to-medium, medium-to-high, high, and extremely high. The 17 countries with extremely high water stress are: Qatar, Israel, Lebanon, Iran, Jordan, Libya, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Eritrea, United Arab Emirates, San Marino, Bahrain, India, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Oman, and Botswana.

Note 2: We searched the national (Tokyo) morning edition for the following keywords: water, pollution, conflict, water source, scramble, friction, resources. From these, we selected only articles related to water and conflict.

Writer: Yosif Ayanski

Graphics: Yow Shuning

日本の報道量の少なさに驚きました。