In August 2024, Bangladesh reached a turning point that wrote a new page in its history. Former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who had held power for more than 15 years, fled to neighboring India and was forced to resign. Behind the rapid chain of events that toppled this long-running administration was a protest movement led by students and other citizens. The protests drew attention at home and abroad, but students serving as the catalyst for political change is nothing new in Bangladesh.

Looking back at the country’s history, student movements have consistently been a key driving force propelling social transformation. Since 1947, when Bangladesh became part of Pakistan after the end of British rule, students have played a decisive role in shaping the nation’s future—from the language movement to the independence struggle and protests against military rule. The student-led demonstrations that culminated in the 2024 toppling of the government followed this historical trajectory in Bangladesh, while also displaying new contemporary characteristics, such as online coordination and the rapid spread of protest through digital platforms.

This article reviews student movements in Bangladeshi history and analyzes how the 2024 student movement reshaped the country’s political landscape. It also considers how today’s youth may continue to drive social change and what lies ahead for Bangladesh.

Students participating in a protest (Photo: Mohammad Tanbiruzzaman Koushal / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Bangladesh overview: the economy and its challenges

Bangladesh is located in South Asia, bordered by India to the west, north, and east, Myanmar to the southeast, and the Bay of Bengal to the south. As of 2025 it is the world’s 8th-most populous country, with about 170 million people. About 91% of the population is Muslim, and most are Bengalis who speak Bengali, the official language.

Bangladesh’s economy is primarily driven by agriculture and the apparel/garment industry. Because much of the country lies in the vast Ganges Delta formed by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, it is rich in water resources and geographically well-suited to agriculture. In 2023, its rice production ranked third in the world, after China and India. On the other hand, these abundant water resources also frequently bring devastating floods. In August 2024, massive flooding affected 5.7 million people, leaving many isolated and unable to access relief, causing severe impacts.

Scenes of flooding in Bangladesh (Dhaka, 2020) (Photo: Sk Hasan Ali / Shutterstock.com)

Beyond agriculture, the clothing and garment industry also underpins Bangladesh’s economy. Garments account for 86.5% of total exports, cementing the country’s status as a key supplier to the global fashion industry. However, behind this lie unfair trade relations dating back to the colonial era and exploitative labor conditions—such as wages that are less than 1% of a garment’s sale price. This reflects the fashion industry’s structurally unfair model that exploits producers working in poor conditions.

While some argue that Bangladesh—once called “the poorest country in Asia”—is now experiencing economic growth and momentum, in reality poverty still casts a deep shadow over the country. Using the “ethical poverty line (※1)” as a benchmark, as many as 79% of the population live below this threshold.

These economic conditions and persistent poverty have triggered serious challenges, including high youth unemployment, extremely low wages, and a brain drain. According to World Bank statistics, the overall unemployment rate in 2023 was about 5.1%, but it exceeded 16% among youth. Although there are more than 2.6 million unemployed people in the country, roughly 83% of them are between 15 and 29 years old, highlighting the severity of youth unemployment. Against this backdrop, data shows that 1.3 million Bangladeshis left the country as labor migrants in 2023, indicating a pronounced outflow of the most educated generations. Such economic realities inevitably weigh heavily on students facing the job market ahead.

East Pakistan and the Language Movement

The red circle at the center of Bangladesh’s flag symbolizes the blood shed by those who fought through the many struggles leading up to independence. Among those who cannot be overlooked are students. Let us now look at the formation of Bangladesh and the history of its student movements.

Before the establishment of present-day Bangladesh, the Bengal region—encompassing what is now Bangladesh and India’s West Bengal—consisted of 16 small kingdoms that underwent repeated mergers and absorptions. In the mid-16th century, Bengal came under Mughal rule and flourished. British power expanded in the 18th century, and from 1765 the area—along with what is now India and Pakistan—became part of British India. When British rule ended in 1947, British India was partitioned into India, comprising mainly Hindu-majority areas, and Pakistan, comprising mainly Muslim-majority areas. However, Pakistan consisted of two noncontiguous parts separated by India: West Pakistan (now Pakistan) and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), together forming one country.

Immediately after independence as East and West Pakistan, the question of the national language came to the fore. As West Pakistan came to dominate the politics of the entire country, a 1947 nationwide education summit in Karachi (now the capital of Sindh province in Pakistan) decided that Urdu and English—languages primarily spoken in West Pakistan—would be Pakistan’s official languages. Since 56% of Pakistan’s population—mostly those in East Pakistan—spoke Bengali as their mother tongue, people protested this unfair imposition and demanded that Bengali be recognized as one of Pakistan’s national languages. In December 1947, students in East Pakistan held a gathering on the University of Dhaka campus and formed a National Language Action Committee called the “Rastrabhasha Sangram Parishad.” In 1948, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman founded the Chhatra League, establishing a student movement organization that symbolized the vanguard of the struggle for the freedom and independence of the Bengali people in history.

Led by Rahman, students in East Pakistan protested the exclusion of Bengali from the Constituent Assembly, the absence of Bengali script on Pakistani coins and stamps, and the use of only Urdu in the Navy recruitment test. In 1948, these protests took the form of a general strike and repeatedly demanded that Bengali be recognized as one of Pakistan’s official languages. During this general strike movement, students were injured in clashes with police but continued marching, and they joined picketing to halt employees and business operations in order to sustain and strengthen the strike.

As a result, while the central government in West Pakistan accepted some demands, it refused the core demand to recognize Bengali as a co-official language. The government enforced Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to restrict unlawful assemblies in Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, thereby banning all gatherings. Despite this, on February 21, 1952, thousands of students from various schools and colleges in Dhaka gathered on the University of Dhaka campus and defiantly held an assembly in violation of Section 144. As armed police waited outside the gates, students filed out in groups chanting the slogan “Rashtrabhasha Bangla Chai” (“We want Bengali as the national language”), clashing with police as they asserted their linguistic rights. During this Language Movement, which continued until 1956, several students lost their lives, and many others were injured and arrested. Thanks to this sustained movement, the region that is now Bangladesh—then East Pakistan—was able in 1956 to make Bengali a joint state language alongside Urdu, West Pakistan’s official language.

The rise of Bengali identity among the people of East Pakistan during the 1952 Language Movement laid an important foundation for the independence movement from Pakistan in 1971. In 1999, to honor the victims of the Language Movement of February 21, 1952 in Bangladesh, UNESCO designated “International Mother Language Day.”

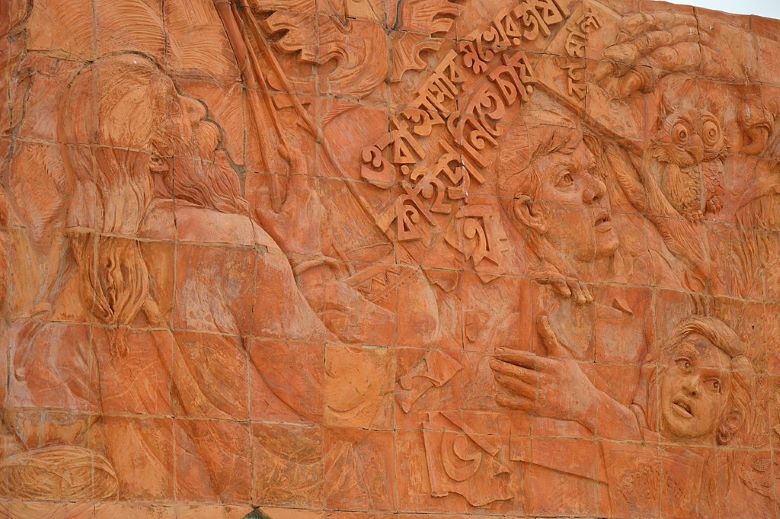

One of the exhibits at the Museum of Independence in Dhaka. The Bengali text reads, “They are trying to take our language from our mouths.” (Photo: Biswarup Ganguly / Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY-3.0])

East–West Pakistan tensions and the Liberation Struggle

One might have thought that the struggle between East and West Pakistan would subside after the Language Movement secured the right to make Bengali a state language. But through the 1960s, as West Pakistan gained advantage in industrial profits and access to education and employment, dissatisfaction among East Pakistan’s intellectuals and students grew. In 1962 in particular, large numbers of students joined protests against constitutional reforms introduced by General Ayub Khan that marginalized East Pakistanis, and many students were killed in clashes with police. As a result of these sustained protests, the Ayub government was forced to suspend and roll back reforms, and student movements began to wield influence beyond that of party-led protests.

Later, Rahman—the student movement leader—became head of the Awami League. In the 1970 national elections in Pakistan, the Awami League in East Pakistan won a landslide and should have taken power. Nevertheless, the West Pakistan-based government—President Yahya Khan and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP)—refused to hand over power to prevent control from shifting to an East Pakistani party. In response, calls for independence from Pakistan intensified in East Pakistan, and Rahman delivered a protest speech against West Pakistan.

As demands for independence in East Pakistan grew, the Pakistani military launched Operation Searchlight in Dhaka in 1971, and repression followed, including the killing of hundreds of students in Dhaka. Death toll estimates range from 300,000 to 3 million, and hundreds of thousands of women were subjected to rape.

India sheltered more than 10 million people who fled from East Pakistan to escape the repression. In the liberation struggle, the “Mukti Bahini”—armed forces composed largely of young volunteers and known as the “Freedom Fighters”—stood at the front lines against the Pakistani military. The Indian government also provided them with weapons and training, intervening in the war. This became a decisive support for victory, and by the end of 1971 East Pakistan won independence as Bangladesh.

A poster depicting fighters who fought for independence, displayed at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka. (Photo: Adam Jones / Flickr [CC BY 2.0] )

The role of the student movement in the 2024 toppling of the government

In 1975, amid the post-independence turmoil, Rahman was assassinated, and his daughter Sheikh Hasina took over leadership of the Awami League. She governed from 1996 to 2001 and then for another 15 years from 2009, but her rule increasingly turned authoritarian, marked by repression of dissident lawyers and journalists, imprisonment in secret facilities, crackdowns on opponents and critics, and corruption. The protests in Bangladesh in 2024 were fueled by long-simmering discontent with this authoritarian rule and grievances rooted in the country’s economic fragility and poverty during her 15-year tenure.

Among the grievances against the government, the most direct catalyst was the resentment toward the quota system that reserved government jobs for freedom fighters—veterans of the 1971 Liberation War—and their descendants. With economic and employment opportunities limited, this system appeared to youth—who faced particularly severe conditions—as a symbol of “inequality,” becoming a focal point of protest.

By a presidential order in 2018, the preferential quota that had existed since 1972 was deemed unconstitutional and abolished. However, in June 2024, the Supreme Court struck down that decision, reinstating a 30% quota for freedom fighters in civil service recruitment, thereby bringing the system back and reigniting protests. Students pushed back, and they mobilized through social media, initially launching peaceful demonstrations.

When the Hasina government refused to meet the students’ demands, the protests intensified. The situation changed dramatically after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina referred to the protesters as “Razakars” in a remark.

“Razakar” is a derogatory term for those who collaborated with the Pakistani army against freedom fighters during the 1971 war of independence. The word evokes war crimes, including the killing of many Bengalis and minorities and the rape of women. In Bangladesh it is synonymous with “traitor” or “anti-national.” Hasina’s comment prompted a powerful backlash among students. Underlying the criticism was also a grievance that, because the Awami League was founded by those who fought in the liberation war, maintaining the quota system unfairly benefited the party’s supporters. Hasina said, “If those who fought for independence cannot receive (quota) benefits, should Razakars receive them?” This statement ignited students’ anger. The self-mocking slogan “Who are you? Who am I? Razakar, Razakar!”—in essence, “Are we traitors?”—emerged, and students rallied around it.

A protest demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina (August 4, 2024, Dhaka) (Photo: MDSABBIR / Shutterstock.com)

In response to the growing backlash, the Hasina government shut down internet communications, imposed a curfew authorizing live fire upon violations, and intensified crackdowns by armed police. Between July 16 and September 9, 2024, 875 people were killed and more than 30,000 were injured. Reports also noted that students made up 52% of the deaths—the largest share recorded. At this point, the movement’s focus shifted from opposing only the quota system to challenging authoritarianism. Protesters narrowed their initial nine demands—which had included an official apology from Hasina and the release of arrested students—to a single demand: “the resignation of the Hasina government,” and the movement expanded nationwide.

The decisive turning point that led to Hasina’s flight was the massive march in Dhaka on August 5, 2024. A call to “gather at Shahbagh Square in Dhaka at 2 p.m.” spread, and faced with more than five million protesters assembled from across the country, the Hasina government was forced into a situation where it had to step down. In a country facing poverty, a movement that began as youth protests against inequality in employment opportunities ultimately toppled a long-entrenched regime.

How online tools transformed the shape of protest

One factor that enabled such strong cohesion in a student movement capable of bringing down a government was the amplification of protest through online tools.

Soon after the government began its crackdown, a 30-second video showing student Abu Sayeed—unarmed and a student leader of the protests—being shot by police spread on Facebook. It sent shockwaves across social media, unleashing a surge of outrage over the illegality of the state’s use of force, and participation in the protests rapidly swelled. Social media accounts such as The Bangladeshi Voice shared updates, as did the music of a rap artist that became an anthem of the movement.

Using a range of online tools, student leaders worked to raise awareness and encourage expressions of solidarity with events unfolding in Bangladesh. Anticipating network shutdowns, they also adopted applications that can function offline, such as Bridgefy, to organize and sustain protests—making digital technology a new tool for cohesion in the 2024 movement.

After Hasina resigned, students hoist the national flag at the Prime Minister’s Office (2024, Dhaka) (Photo: Sk Hasan Ali / Shutterstock.com)

Student politics made compulsory

The protests unfolded through the mobilization of students demanding a change of government. However, not all students participated; many students stood on the side of the ruling party. The Awami League’s student organization, the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), had an estimated 100,000 student members.

After the regime collapsed, people associated with the ruling Awami League became a new target during the protests. BCL students and hundreds of Awami League politicians and party workers were attacked and killed; many went into hiding or attempted to flee and were detained. With Hasina ousted and in flight, they had no protection and could not return to education. Some have warned that excluding the BCL—which counts an estimated 100,000 student members—would be dangerous.

Moreover, students who sided with the Awami League did so within a structural strategy orchestrated by the former regime. The following is based on an interview conducted by the author with a University of Dhaka student on December 24, 2024, offering a glimpse into the political structure inside universities.

Over nearly 15 years in power, the Awami League placed allies in university administrations and installed leaders of student political alliances in dormitories. At public universities, many students come from distant rural areas and are financially unstable, leaving dormitories as their only accommodation option. When newly enrolled students sought dorm placements, they were confronted with conditions: “If you want to live in the dorm, first join the Awami League’s student politics and do whatever you’re told.” In this way, all dorm residents were effectively forced to participate in student politics and programs. Whether ill or preparing for exams, students had no choice but to attend political programs and obey leaders if they wanted to secure a place to sleep.

The University of Dhaka library. A mural depicting Rahman has been graffitied with the name of Abu Sayeed, who was killed by police, and the word “Revolution.” (Photo: Yahya /Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY-SA-4.0] )

In dorms, as many as 20–25 students were sometimes assigned to rooms meant for eight. Attending daily programs, posting positive content about the Awami League online, and spying on students who might belong to opposition parties were the only ways to secure a more comfortable room. At times—especially when the Awami League felt threatened by opposition parties or the public—these students were forced to take up arms and fight mobs or rival parties.

That said, some students came to support the Awami League of their own accord and acted for personal gain. In other words, there were two kinds of students who cooperated with the Awami League: (1) those who had no choice due to their socioeconomic circumstances, and (2) those who sided with the Awami League voluntarily. The former were the majority. Others supported the Awami League to obtain recommendation letters for their future or to secure government-related jobs.

Through such structural political maneuvering within universities, the Awami League was able to keep opposition forces in check.

The “second liberation” and where Bangladesh is headed

Student movements in Bangladesh have always been central at key turning points in the nation’s history. The upheaval of 2024 was no exception: students shook the established order and achieved both a change of government and the dismantling of an unequal system. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to say that Hasina’s resignation solved all of Bangladesh’s challenges. Beyond discontent with the previous regime lies a structural poverty that shadows the country. The protests reflect global economic inequalities. Bangladesh’s textile and fashion industries rely on low-cost labor to export products to high-income countries. As a result, profits accrue to multinational corporations in wealthier countries while domestic poverty remains entrenched. Such unfair trade is not merely a national problem but a symbol of inequality generated by global economic structures. The 2024 political upheaval in Bangladesh underscores challenges that the world should recognize as a shared responsibility.

Women working in a ready-made garment factory (Dhaka, 2022) (Photo: Rehman Asad / Shutterstock.com)

Many Bangladeshis are calling the fall of the Hasina government a “second liberation,” a transformation following the country’s independence in 1971. The interim government led by Muhammad Yunus, which began functioning after Hasina’s resignation, includes student leaders as well as representatives of minorities and NGOs. It is arguably both a symbol that foreshadows a new Bangladesh as a “second liberation” and a first step toward the democratic change that students demanded. Even so, concerns remain over whether leaders with limited governing experience can address the country’s structural problems. Now that protests against the former regime have ended, how will the country overcome internal divisions and chart a path to the next government? The unity forged by youth—going beyond mere protest—may become the guidepost for Bangladesh to truly achieve a “second liberation.” The country’s turning point is, in many ways, just beginning.

※1 The World Bank’s extreme poverty line is living on $2.15 per day. However, this line does not fully capture real conditions of poverty. GNV therefore uses an ethical poverty line ($7.40 per day). The poverty rates available from World Bank data use thresholds of $7.0 and $7.5 per day. For calculations we used $7.5, the value closest to the $7.40 ethical poverty line. For more details, see GNV’s article “How should we read global poverty figures?”.

Writer: Chiori Murata

Graphics: Ayane Ishida

東西のパキスタンが、その後パキスタンとバングラデシュの二国に別れたことまでは、知っていたが、その後のそれぞれを知る機会はほとんどなかった。

このレポートでは、バングラデシュの学生運動の推移に焦点を絞っていて、丁寧な分析から、独立後の政治の難しさを掬いあげた点が優れていると感じた。

バングラデシュの歴史を、学生の行動と目線から行っている点に特に興味深さを感じました。単なる報告書ではなく、実際にインタビューを通して公教育の問題点を指摘している点が印象的でした。

バングラデシュの事前知識無しで読んでも面白い!

バングラデシュの学生運動の系譜が今回の政変にどう繋がったのか、わかりやすく読むことができました。学生リーダーが暫定政権に入り、彼らと相対する人々をどう包括し国づくりを進めていくのか、今後が気になります。

ベンガル語が公用語から外されたということで大きな運動がおこり、最終的に公用語に入れることに成功したという話が印象的でした。実利の面だけでなく、言語は人のアイデンティティにも関わる大きな問題なのだということを強く感じました。

学生運動が政権を変えるという、壮大な歴史的ストーリーを包括的に理解することができ、非常に面白かったです。また、学生運動のためにSNSツールが活用されるというのが、非常に驚きでした。日本におけるSNSの活用方法とは全く違ってて、面白いなと感じた。

ラジャカールが正義だと考えられるが、記事の後半では、アワミ連盟側につかざるを得なかった人がラジャカール側に殺害されたりと、どちらの勢力に対しても公平な見方ができる記事の構成ですごいと思いました。

政治においてどちらが悪かを決めつけることなく、両者の背景を理解することが大事だと気づきました。また、ファストファッションがバングラデシュの貧困の悪循環に起因していること、それを着る私達にも責任があるという点で、バングラデシュがより身近に感じるようになりました

この記事を読んでくださり、そしてコメントをしてくださりありがとうございます!

この記事を書いた村田千織です。

この記事では、今回の政変でアワミ連盟(政府)側に対抗する立場を取った学生と、一方でアワミ連盟側に傾倒していった学生の例を取り上げていますが、アワミ連盟に対抗した(今回の政変を主導した)学生たちはラジャカールではありません。本文の中で、学生たちのスローガン「あなたは誰?私は誰?ラジャカール、ラジャカール!」を取り上げましたが、それは学生たちがハシナ首相の発言を皮肉に捉えたものなのです。バングラデシュで非国民を意味する侮辱的な言葉で、独立に貢献しなかった人々を表す「ラジャカール」を使ってあえて自分たちを表現することで、いわば、「ハシナ首相は私たちを非国民とでも言いたいのか?」という怒りと共に対抗したのです。