In July 2020, GNV published an article titled “Education for All Children: What Should Education Reporting Look Like?” that examined global education issues such as educational disparities and the state of reporting on them. More than four years have passed since that publication, yet challenges surrounding education continue unabated. Among these challenges, this article focuses in particular on COVID-19, armed conflict, poverty, and gender to track the current state of education worldwide. It also looks at how these topics have been communicated to the public through the media.

In the 2020 article, we analyzed five years (2015–2019) of international reporting in the Mainichi Shimbun morning edition (※1). The number of articles about global education over those five years was limited to 172, and their content showed biases. Four years on, interest in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which also focus on education, has been growing in Japan, but has reporting on education around the world changed?

In this article, we therefore examined education-related pieces among international-page articles in the Asahi Shimbun morning edition over the most recent five years, from November 1, 2019 to October 31, 2024, and identified their content and the countries/regions covered (※2). By analyzing these articles, we also explore global education challenges and how they are reported.

Class under a tree: Malawi (Photo: Tamandani-Lungu / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

COVID-19 and education

First, let us look back at how COVID-19 affected education. In December 2019, the novel coronavirus was detected in China. The virus then spread worldwide; in January 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and in March of the same year stated it could be considered a pandemic.

As part of infection control measures, many countries restricted people’s movements, and many schools were closed. At the peak of school closures in April 2020, it is estimated that 1.6 billion students—about 94% of learners worldwide—were unable to attend school. Some countries were largely able to continue learning via online classes, but most of these were high-income countries; many low-income countries could not provide adequate internet access, resulting in many students losing learning opportunities altogether. As of December 2020, the share of school-age children able to connect to the internet at home averaged 87% in high-income countries, but only 6% in low-income countries (※3).

The loss of learning opportunities has been reflected in actual changes in students’ academic performance, with an increase in the proportion of children experiencing “learning poverty.” “Learning poverty” is a concept jointly developed by the World Bank and UNESCO, referring to a situation in which a child cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10. As a result of the pandemic, the share of children in learning poverty in low- and middle-income countries increased by roughly one-third from the pre-COVID-19 level of 57%, reaching 70% in 2022.

Children wearing masks and face shields as COVID-19 measures: El Salvador (2021) (Photo: USAID, El Salvador / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The impact was most severe in Latin America and the Caribbean, where the share of children in learning poverty increased from about 50% to about 80%. COVID-19 spread intensely there; although the region accounts for only 8% of the world’s population, it suffered roughly 30% of global COVID-19 deaths. As a result, it experienced the world’s longest school closures, losing an average of 174 days of in-person instruction—more than four times other regions—compared with the rest of the world. Insufficient internet access also hindered efforts to support learning.

The next most affected region was South Asia, where the share in learning poverty is estimated to have risen from about 60% to about 78%. In Sub-Saharan Africa, although the rate of increase was comparatively smaller, educational environments were vulnerable even before the pandemic; the learning poverty rate rose three points from about 86% in 2019 to a very high level of about 89% as of 2022. In South Africa, more than 2,000 schools were looted during lockdown, further straining the education system.

However, these impacts were by no means limited to low- and middle-income countries. In the United States, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), administered periodically by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), reported a significant decline in math and reading scores from 2019 to 2022 among students in 4th and 8th grades (roughly equivalent to Japan’s elementary 4th and junior high 2nd years).

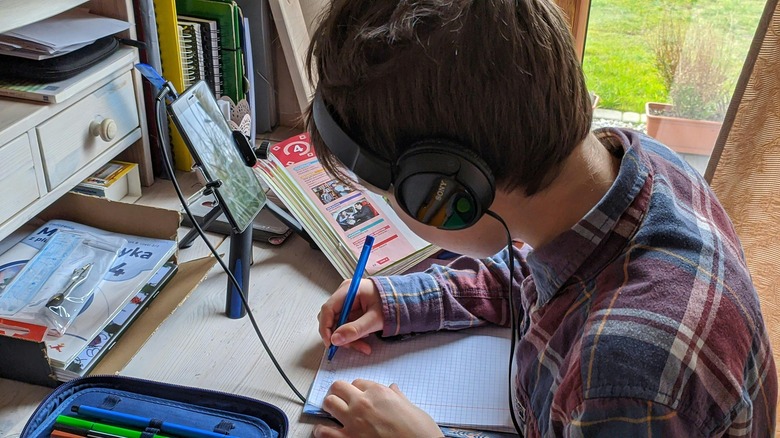

A child studying online during the pandemic (2020) (Photo: Adam Sondel/ Pexels [Legal Simplicity])

COVID-19 and education in the media

How were these education impacts of COVID-19 reported in Japan? In the Asahi Shimbun’s international coverage, there were only 13 articles over five years (November 1, 2019–October 31, 2024, morning edition) concerning COVID-19 and schools or education, and all but one were from 2020, the peak of the pandemic. The single article published after 2020 covered the decline in U.S. NAEP results noted above. Of the 12 articles in 2020, half (6) were about Asia, and one-third (4) about Europe; there was also one article on Africa, and one addressing global impacts. Despite the region’s having the longest school closures, there were no articles mentioning the pandemic’s impact in Latin America and the Caribbean.

All of these articles focused on national school-closure measures. Specifically, many reported that, as in-person classes became difficult to hold, countries primarily in Europe and in China and South Korea were shifting to online learning, and that COVID-19 testing was being strongly encouraged for exam takers. The sole article on Africa reported that Kenya, faced with prolonged school closures at all primary and secondary schools, decided to have all students repeat the year. Except for the U.S. piece noted above, none addressed declines in children’s academic performance. Nor were there articles on countries unable to conduct online classes due to inadequate internet infrastructure.

Armed conflict and education

In addition to sudden crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, the many ongoing armed conflicts continue to have profound impacts on education. Examples include the conflicts still unfolding in Sudan, Palestine, Burkina Faso, Yemen, and Ukraine.

According to UNHCR’s 2023 Refugee Education Report, the number of school-age refugees surged by nearly 50% from about 10 million in 2022 to about 15 million, and more than half—over 7 million children—were out of school. While the global average gross enrollment rate in primary education is 103% for boys and 101% for girls (※4), the gross primary enrollment rate for refugees is only 63% and 61%, respectively. Even when refugees access education in host countries, differences in curricula and language often pose barriers.

Children heading to class: Burkina Faso (2021) (Photo: European Union, Olympia de Maismont / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Burkina Faso in West Africa offers a stark example of conflict’s impact on education. Under government policies, the primary school enrollment rate (※5) had improved steadily since 1980, but it fell sharply due to the armed conflict that erupted in the late 2010s. Although Burkina Faso had been stable for decades, it was affected by regional destabilization, and armed groups began carrying out frequent terrorist attacks and assaults on civilians. A ranking named Burkina Faso the most terrorism-impacted country in 2023. Consequently, a quarter of schools in the country were forced to close that year, affecting 1 million students. The primary school enrollment rate fell to 74.4% that year.

In conflict-affected areas, education plays an even greater role than it does elsewhere. Beyond gaining basic, essential skills such as literacy and numeracy, children can develop social skills through school life. They can also learn nonviolent approaches to problem solving, potentially increasing opportunities for youth to contribute to peacebuilding. Schools can sometimes physically protect children, helping prevent violence, abuse, and recruitment by armed groups. They can also provide psychosocial care for conflict-related trauma.

Armed conflict and education in the media

As we have seen, conflicts are proliferating worldwide, and adequate education remains out of reach in many places. How has this been reported? Over five years (November 1, 2019–October 31, 2024, morning edition), the Asahi Shimbun ran just nine articles on conflict and education. Of these, seven were about the war in Ukraine, one about Sudan, and one about global impacts. More than half of the Ukraine-related articles introduced local individuals supporting children. The piece on Sudan similarly introduced a Japanese staff member of an international NGO volunteering at a local supplementary school. None focused on the actual circumstances facing children on the ground due to conflict. There were no articles on Burkina Faso as discussed here, nor on schools and education in Gaza where intense attacks continue. The strong regional bias makes it hard to say the coverage reflects global realities.

Children unable to attend school due to armed conflict: Gaza (2024) (Photo: UN Women, Suleiman Hajji / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Poverty and education

Thus far we have seen how education is obstructed by disease and conflict. However, the largest factor obstructing children’s education is poverty. Globally, children of primary school age in the poorest households are about four times as likely to be out of school as those in the richest households.

In low-income countries, there tend to be fewer schools to begin with and a shortage of teachers, and child labor also plays a role. The situation is particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is facing rapid population growth: it is estimated that an additional 15 million teachers will be needed by 2030 to provide adequate primary and secondary education. South Asia is also short by 7.8 million teachers. In short, a major challenge for low-income countries is insufficient resources allocated to education.

Poverty often persists across generations, and this intergenerational cycle is closely linked with access to education. When poverty makes it difficult to send children to school, they lose opportunities to acquire knowledge and skills, making it harder to escape poverty. Those children then also tend to have fewer chances for education, causing poverty to reproduce and become entrenched across generations. Education is one means to break this cycle.

Low-income countries are also especially vulnerable during crises such as disasters. For example, in South Asia, Pakistan has a fragile economic base including infrastructure; it also faces large income, regional, and gender disparities, and low social indicators in health and education metrics. In this already challenging context, Pakistan suffered historic flooding starting in June 2022. More than 33 million people were affected, one-third of the country was submerged, around 27,000 schools were damaged or destroyed, and over two million children were unable to attend school. Many of the hardest-hit districts were already underdeveloped, and even before the floods, one in three children were out of school. With electricity and internet connectivity severed in many areas, remote learning has also been difficult. This is a clear example of how, in unprecedented crises such as disasters, it is the poor who are most affected.

Remains of a school destroyed by flooding: Pakistan (2010) (Photo: DFID, Magnus Wolfe-Murray / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Poverty and education in the media

As noted above, despite the close link between solving poverty and education, the situation has not improved, and poverty continues to severely impede access to education. Yet in the Asahi Shimbun there was only one article over five years (November 1, 2019–October 31, 2024, morning edition) focusing on children unable to access education due to poverty. It did not detail the current situation or public initiatives aimed at solutions, but instead introduced a free, privately run cram school in India providing education opportunities to such children. While this article has discussed media gaps in coverage of education issues related to COVID-19 and conflict, interest in poverty and education appears to be even lower, despite its broad impact.

Gender and education

Gender disparities also exacerbate education problems. For example, domestic chores performed by children can affect schooling, and 90% of children engaged in domestic labor worldwide are girls aged 12–17. Poverty is also related: when families cannot afford to send all children to school, many prioritize boys’ education. In conflict zones, girls are 2.5 times more likely than boys to be out of school.

Furthermore, 12 million girls worldwide are forced into marriage before age 18 each year. The prevalence of child marriage varies by country, but 42% of women and girls who have experienced child marriage live in South Asia. In Africa, rapid population growth is expected to raise the number of girls experiencing child marriage to 180 million by 2050, according to estimates. Many are made to leave school upon marriage, reaching adulthood without sufficient educational opportunities.

A girl cooking for her family: India (Photo: India Water Portal / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

While such gender-related issues often arise at the household or community level, national policies can also restrict girls’ education. In Afghanistan, for example, since the Taliban seized power in 2021, girls have been barred from secondary education, and this measure remains in place.

Gender, education, and their coverage

How were these gender-and-education issues reported? Of the 104 education-related international articles in the Asahi Shimbun over five years (November 1, 2019–October 31, 2024, morning edition), only five concerned gender and education. Three addressed Taliban restrictions on girls’ education in Afghanistan; one reported that France banned the Islamic traditional garment “abaya” for female students in public schools; and one introduced a group in Argentina advocating the abolition of gendered language forms. There were no reports on domestic labor, child marriage, or gender gaps in education in South Asia or Africa.

The overall picture of education-related international reporting in the Asahi Shimbun

We have reviewed crisis-hit education settings worldwide along with the trends in the Asahi Shimbun’s international reporting on them. Here we analyze the overall picture of the paper’s education coverage. First, there were few articles on education to begin with. Over the five years from November 1, 2019 to October 31, 2024, the morning edition carried only 104 such pieces—roughly 20 per year, fewer than three per month.

There was also a strong geographic bias. Of the 104 articles, 24 concerned China, 16 the United States, and 8 South Korea; these three accounted for about half of the total. There were only five pieces on the African continent—which faces particularly acute education crises—over the five years. And even among those five, none addressed chronic issues: three were about student abductions at a school in Nigeria, one reported on COVID-19 school closures, and one profiled a Japanese volunteer working at a school in Sudan.

As these breakdowns show, coverage of countries geographically distant from Japan or low-income countries is limited, while articles about countries with closer geographic or political ties to Japan and high-income countries are more common. The high number of pieces on China stems partly from the frequent protests at Hong Kong universities in 2019 and the associated coverage, as well as from China being where COVID-19 was first detected.

There were also content biases. Of the 104 articles, those about “incidents” such as school shootings and attacks were most common (21), spanning China, the United States, the Czech Republic, Serbia, Nigeria, and others. Next were 13 pieces on “protests,” such as demonstrations at U.S. universities against Israeli attacks on Gaza and student resistance to the government in Hong Kong. Articles on “regulation” (e.g., textbooks) and on “COVID-19” each totaled 11, and these four categories accounted for more than half of all coverage. Most “regulation” pieces concerned China and Russia.

By contrast, only seven articles addressed the long-term, severe issue of “education quality.” A common trend in reporting is to focus on events with clear developments and direct relevance to public safety, such as incidents and protests. Consequently, deeply rooted but less visually apparent issues—such as declines in education quality and the existence of out-of-school children—receive less attention. As noted, there was only one article on “poverty,” accounting for less than 1% of the total. There were no articles about the chronic worldwide shortage of teachers.

In our earlier analysis of the Mainichi Shimbun’s international coverage four years ago, China was also the most covered country, followed by the U.S. and South Korea, together accounting for more than half of the total. In terms of content, “incidents” were most common, followed by “protests,” while articles on chronic education issues were very few. Although the newspaper differs, there has been no major change in reporting trends by country or topic.

Conclusion

Despite education being under threat and quality declining in many parts of the world, international reporting on these issues in Japan remains scarce, and such topics rarely attract major attention. The United Nations’ SDGs Goal 4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” Although the SDG deadline is 2030, as this article has shown, educational disparities continue to widen globally, and children deprived of learning opportunities remain numerous. With only about five years left, it is difficult to say that a path toward achieving Goal 4 is visible, let alone achievable.

In recent years, interest in the SDGs has been growing in Japan. However, attention varies greatly by goal. While climate action receives frequent coverage, the status and efforts related to SDG 4 on education attract little focus. Moreover, even SDG-related reporting tends to center on initiatives by the Japanese government and companies, with little focus on the underlying issues. Perhaps the limited interest shown by the country’s political and economic elites in global education problems plays a role.

The SDGs are founded on the principle of “leaving no one behind.” When coverage is sparse or biased, it becomes difficult to recognize the current state of and challenges in global education. Without that recognition, measures to ensure “no one is left behind” will not come into view—and cannot be realized. It is time to reexamine the significance of reporting on education and to call for international coverage that reflects global realities.

※1 Aggregated only the international page of the Mainichi Shimbun morning edition published in Tokyo between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2019 via the Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Mainichi Shimbun Maisaku.” Of the articles whose headlines or body texts included “education,” “student,” “school,” or “high school,” those without body text display or clearly unrelated to education based on their headline and content were excluded.

※2 Aggregated only the international page of the Asahi Shimbun morning edition published in Tokyo between November 1, 2019 and October 31, 2024 via the Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search.” Of the articles whose headlines or body texts included “education,” “student,” “school,” or “high school,” those without body text display or clearly unrelated to education based on their headline and content were excluded.

※3 Refers to countries classified as low income by the World Bank classification.

※4 Gross enrollment can exceed 100% due to the presence of overage learners, such as students who repeat grades or return after years out of school.

※5 In the 1980s, Burkina Faso prioritized improving literacy and school enrollment nationwide. Public education was made free for ages 3–16, and the primary school enrollment rate rose from 44% in 2000 to 89.5% in 2019.

Writer: Tsugumi SUZUKI

Graphics: Virgil Hawkins

教育の問題について、紛争や貧困、ジェンダーなど様々な要因があるにも関わらずそれが報道されていないという問題を知ることができました。不十分、不公平な教育は格差を再生産するという構造的な問題があるため、貧困の連鎖を断つためにも問題そのものにフォーカスが当てられるべきだと思いました。

教育についての報道がなぜ少ないのか、包括的に理解することができ、非常に興味深かったです。特に、コロナ禍の前後で、低所得国における教育現場の現状がそれほど改善されていないのが驚きでした。それに加えて、報道も少なく、なかなか目を向けることができていないんだなと実感しました。

教育というと比較的身近な話題だから、報道されやすいのかと思っていたが、教育の質のような、教育の根幹に関するものよりも、銃撃事件など、学校と関連する事件や抗議活動が注目されていることが意外だった。私は特にジェンダーに興味があり、児童婚や家庭内労働によって女子が教育を受けられなことが衝撃的だった。

また、低所得国で教育を十分に受けられない子どもたちがいるという事実そのものに意外性がないからこそ、認知度が高まらないと思う。また、ジェンダー、自然災害、紛争、コロナ、貧困などが取り上げられたが、児童労働なども教育の機会を奪う原因であり、私達が気づかないところで誰かの教育の機会を奪っている意識を持たせることが大事だと思う。

コロナ後の教育の現状、その報道に関して、入念に調べられていて非常に勉強になりました。教育という取り上げられにくい、関心を集めにくいテーマをわかりやすくまとめられていて、少しでも多くの人に教育に関心を持ってもらうきっかけになったのではないかなと思います!同時に、これだけ深刻な問題である教育にどうすれば人々が関心を持つのか考えさせられるきっかけになりました。