In November 2024, Somaliland, located in the Horn of Africa, held its fourth presidential election, with more than 1 million people voting. As a result, opposition leader Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (known as Irro) declared victory, and a democratic and peaceful transfer of power is expected.

Somaliland conducts multiparty elections under its constitution. It maintains governing institutions comparable to other states—including the legal system, military, police, and bureaucracy—and circulates its own currency. In 1991 it declared secession from Somalia and achieved de facto independence. However, no UN member state recognizes Somaliland as an independent country.

What drove Somaliland to secede from Somalia, and why has it not been recognized by other countries? This article explores these questions as well as the challenges Somaliland currently faces.

目次

Historical background

For more than 1,000 years, the coasts of present-day Somalia and Somaliland hosted multiple ports that linked Africa with the Arabian Peninsula and beyond. Many people in the region belong to the group known as Somalis, sharing a language (Somali), religion (Islam), and culture. During the medieval period, several Muslim sultanates were established, but no political entity emerged that ruled the entire area. Many Somalis in this era were nomadic pastoralists who moved in search of grazing.

The Ottoman Empire occupied parts of present-day Somaliland in the 16th century, but as it began to weaken, Egypt extended its influence over the Somali region. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, European interest in the region rose, and Britain, Italy, and France moved in, beginning to compete for control. In the area that now constitutes Somaliland, Britain declared and occupied a protectorate. Italy occupied the rest of Somalia and present-day Eritrea. France controlled what is now Djibouti (then French Somaliland). A series of agreements between these European powers and the uncolonized Ethiopian emperor delimited borders in the Horn of Africa.

Resistance to European occupation also emerged. Although clan (Note 1) identities were relatively strong in the region, this resistance fostered the rise of Somali nationalism, which pushed for the unification of Somali-inhabited areas. On June 26, 1960, the former British Somaliland gained independence, and five days later the former Italian colony (present-day Somalia) also became independent. The two immediately united as the Somali Republic. Somaliland remained an independent state for less than a week.

However, the union was unstable from the outset. The former Italian colony (the south), centered in Mogadishu, monopolized governance, leaving the former British colony (the north) in a politically and economically disadvantaged position. The situation worsened after General Mohamed Siad Barre seized power in a 1969 coup. Barre’s authoritarian government was repressive across the country, fueling resentment in the north and elsewhere.

Barre’s wars against Ethiopia (1977–1978) destabilized the region and led to intensified central-government repression of the north. In response, anti-government movements such as the Somali National Movement (SNM) emerged in the north in the 1980s. The Barre regime launched a brutal counteroffensive to crush the rebellion. An estimated 200,000 people were killed, and up to 90 percent of Hargeisa, the largest city in the north, was destroyed.

Independence again and state-building

Rebellions also broke out in the south, and armed opposition to the government intensified. Weakened, the Barre regime collapsed in January 1991. At the same time, Somalia’s central government itself fell apart, and warlord groups began to fight for control of Mogadishu. In response to the collapse of the southern government, the SNM called a ceasefire in the north and launched a peace process. The SNM immediately brought together community leaders from across the north, including those who had fought on the Barre side. A ceasefire was quickly reached, and in May 1991, the assembled leaders agreed to dissolve the union with the south and declare independence as the Republic of Somaliland, with Hargeisa as its capital. Unable to restore a central government and still battling over the capital, southern Somalia could not prevent the north’s secession, and Somaliland’s de facto independence became a reality.

After independence, Somaliland was initially governed based on clan power-sharing arrangements. Though lacking external support or recognition, leaders actively pursued peace and state-building throughout the 1990s. In 1993 a peace charter was adopted, and in 1993 and 1997 indirect elections—where only representatives of different groups voted—were held to choose a president. Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal won both and served until his death in 2002.

In 2001 a referendum approved the adoption of a constitution, establishing a multiparty democratic system in Somaliland. Political parties were formed, and in 2003 the first direct (one person, one vote) election under the constitution was held. Elections were subsequently held in 2010, 2017, and 2024, with each producing a new president.

Party leaders sign an agreement on holding the presidential election (2020). Irro (right) later won the 2024 election (Photo: Somaliland Presidency / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

A destabilizing Somaliland

Since its declaration of independence, Somaliland has remained largely stable, but in recent years tensions have risen with Somalia’s neighboring Puntland region to the east. Puntland is nominally part of Somalia but operates as an autonomous state with limited interference from the central government. Both Somaliland and Puntland claim the border-area regions of Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (also known as Buuhoodle) as their own. Somaliland’s claim is that these areas lie within the borders drawn for Somaliland under British rule. Puntland, by contrast, bases its claim on the shared clan identity of people living in the area.

Initially, the dispute between Somaliland and Puntland was political, but in 2007 it escalated into armed conflict. Somaliland forces entered the Sool regional capital of Las Anod and expelled Puntland forces. Dissatisfaction with Somaliland’s governance led to the rise of a third, locally emerged actor. Its name was taken from the initials of the three disputed regions—Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (SSC)—and it later became known as SSC-Khatumo (“khatumo” means a positive conclusion). In December 2022, conflict broke out between Somaliland and SSC-Khatumo; the latter expelled Somaliland’s forces from Las Anod and seized control of parts of eastern Somaliland.

Somaliland has also suffered political setbacks. The presidential election that was supposed to be held in 2022 was postponed twice and ultimately took place in 2024. Financial constraints played a role, but more importantly there were disputes over the timing of the election and over which parties could participate in Somaliland politics. SSC-Khatumo is thought to have exploited this political instability when it went on the offensive in 2022.

An SSC-Khatumo checkpoint in Las Anod (Photo: Danesrmithpl8 / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Relations with Somalia

Somalia still claims Somaliland as its territory, but Somalia itself is not sufficiently consolidated as a state to take substantive steps toward reunification. Although Somalia has succeeded over many years in introducing a federal governance system, in practice the state remains deeply fragmented. For example, in March 2024, the Puntland region announced it would withdraw from the country’s federal system until a referendum on constitutional amendments is held. However, for reasons including security, it is difficult for the public to vote in Somalia, and a nationwide referendum appears unlikely in the near future. Somalia also continues to face armed attacks by the insurgent group al-Shabaab across much of its territory. The combination of these factors explains why it still cannot effectively govern its territory.

In many respects, Somaliland functions more like a “state” than Somalia and has little incentive to reunify. Against this backdrop, talks between the two parties have been held multiple times in the past (2012–2020, 2023). However, none of these talks reached substantive discussions on reunification.

The conflict between the Somaliland government and SSC-Khatumo in eastern Somaliland produced an outcome favorable to Somalia. In February 2023, after pushing back Somaliland forces, SSC-Khatumo decided to break with the Puntland government and announced it would join the Somali federation. In October of the same year, the Somali government accepted and recognized the SSC-Khatumo administration. Thus, a large territory previously under Somaliland’s control returned—at least nominally—to Somalia’s control.

Relations with other countries

In recent years, Somaliland’s ties with other countries have also heightened tensions between Somalia and Somaliland. For example, in 2018 the United Arab Emirates (UAE) signed an agreement to build a military base in Somaliland and train Somaliland forces. The base was later cancelled. The UAE had planned to use the base as part of its military intervention in Yemen. That same year, the UAE, Ethiopia, and Somaliland signed an agreement to develop the Port of Berbera. It was agreed that the UAE company DP World would develop and manage the port. Somalia protested that Somaliland is part of Somalia and only the Somali central government can conclude agreements with other countries on Somali territory.

View of the Port of Berbera (Photo: Lakmi00 / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

In January 2024, Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding with Somaliland regarding access to the port. Under it, landlocked Ethiopia would be able to use a 20-kilometer stretch of coastline near Berbera for its naval forces for 50 years. In return, Ethiopia would formally recognize Somaliland. From Somalia’s perspective, this would mean the presence of an unauthorized foreign military base on Somali territory. Somalia has long relied to some extent on Ethiopian troops stationed in Somalia in its fight against al-Shabaab, but it has said that unless the MoU is withdrawn it will not allow the deployment to continue. In response, Egypt, which is at odds with Ethiopia, agreed to provide Somalia with troops and arms.

Somaliland’s relationship with Taiwan has also been strengthening in recent years. In 2020 they established diplomatic relations and opened representative offices in each other’s capitals. Ties have also been strengthened through aid, trade, and investment projects. A shared reality—both functioning de facto as democracies while remaining largely unrecognized by other countries—binds them together. In response, not only Somalia but also China, which claims Taiwan, has pushed back.

The recognition question

As noted above, Somaliland has gained de facto independence from Somalia and has functioned as a “sovereign state” for more than 30 years.

However, how much this “independence” means depends on Somalia and on other UN member states. The Somali government continues to claim sovereignty over Somaliland, and this position seems unlikely to change soon. Moreover, SSC-Khatumo’s seizure of parts of Somaliland and decision to return to Somali territory appears to have given the Somali government some hope. At the same time, Somalia still fails to function as a state in many respects, and hopes of reunification with Somaliland are slim.

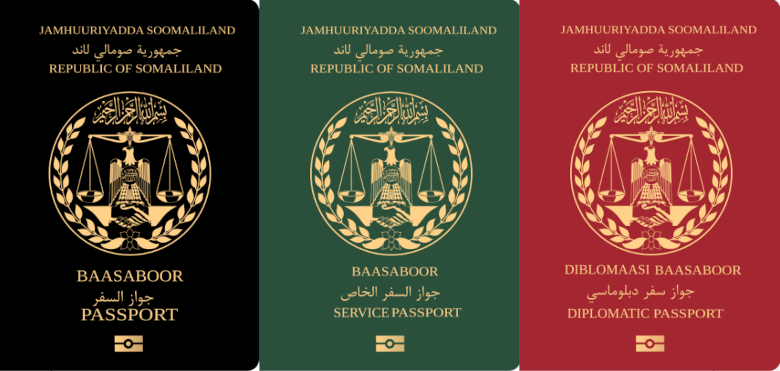

Passports issued by the Somaliland government (from left: ordinary, official/service, diplomatic) (Photo: Siirski / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

As for international recognition, for now only Taiwan—which itself is not internationally recognized as a state—recognizes Somaliland, but Ethiopia has agreed to do so. Some experts see a possibility that Kenya and the UAE may also recognize Somaliland. The African Union’s (AU) posture is a key element in debates over recognition. The AU has in the past taken steps to examine the possibility of Somaliland’s independence, but for now appears reluctant. There is a concern that allowing a border change anywhere on the continent would fuel calls for border changes elsewhere. It is also thought that some AU member states with their own secessionist movements oppose Somaliland’s independence for fear it would set a precedent.

Somaliland’s case for independence can be considered strong. First, Somaliland was once an independent country in 1960, albeit for only five days. It was recognized by 35 countries at the time. Furthermore, Somaliland’s boundaries would follow colonial-era borders, as is the case for the borders of most countries on the continent.

Interestingly, many Western countries maintain informal relations with Somaliland. They provide some assistance and have at times sent election observers when votes are held. Yet these countries also continue to treat Somalia and Somaliland as a single entity. Moreover, as long as Somaliland maintains ties with Taiwan, China will block UN membership.

The fact that Somaliland is not recognized by other countries as a state has many consequences. On the international stage, it cannot participate in deliberations and decision-making at regional and international organizations such as the AU and the United Nations. It is also ineligible for loans from international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Somaliland Police 25th Anniversary parade (2018) (Photo: VOA Somali / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Being treated as part of Somalia also causes other problems. The ongoing armed conflict and frequent terrorist incidents in Somalia hinder investment, aid, and tourism to the comparatively stable Somaliland. One reason is the travel advisories of many countries that do not distinguish Somaliland’s situation from Somalia’s. In addition, because the international ban on arms imports imposed on Somalia due to the armed conflict also applies to Somaliland under international law, Somaliland’s police and other services find it difficult to acquire weapons.

On the other hand, the fact that Somaliland has built a democratic state largely on its own under extremely difficult circumstances raises questions about the benefits of “aid” from other countries. By contrast, despite repeated foreign military interventions and large amounts of aid purportedly aimed at promoting stabilization, peace, and state-building, it is questionable how much Somalia has been able to achieve.

A step forward?

The road ahead for Somaliland will not be easy. It has lost part of its territory in fighting with SSC-Khatumo. And the agreement Somaliland concluded with Ethiopia in January 2024, in which it promised coastal access in exchange for recognition, has greatly heightened tensions with Somalia. Many experts, however, believe the likelihood of this tension escalating into armed conflict is low.

The successful presidential election in November 2024 also arguably presented other countries with the image of a stable, democratic “state.” While it is unlikely to lead to recognition immediately, it may be a step forward in that direction.

Note 1 On clans in Somalia: “While the majority of Somalia’s population identify as Somali and ethnic divisions are relatively few, what is distinctive is the presence of clans. Clans, defined by kinship ties, influence various decisions in daily life in Somalia.”

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Graphics: MIKI Yuna

0 Comments