In recent years, chocolate has been drawing attention not only for its delicious taste but also for its health benefits, and the chocolate market—led by high-cacao varieties—has been expanding.

(Photo: cgdsro / Pixabay)

However, behind the happiness we consumers feel when we eat chocolate and the rising profits of manufacturers lie severe poverty, child labor, forced labor, unfair trade, and more, which are rampant on cocoa farms in West Africa and Latin America. As these issues have attracted attention and can no longer be ignored, major confectionery manufacturers have begun to promote claims such as “we are striving for responsible sourcing,” and in recent years products certified as fair trade have been gradually increasing. Heard on its own, this might suggest the problem is on its way to being solved. But in reality it is not; cocoa bean producers continue to face harsh conditions. If that fact is not reaching consumers, a major reason may be insufficient reporting on the issue. This article explores the problem.

The harsh reality for producers

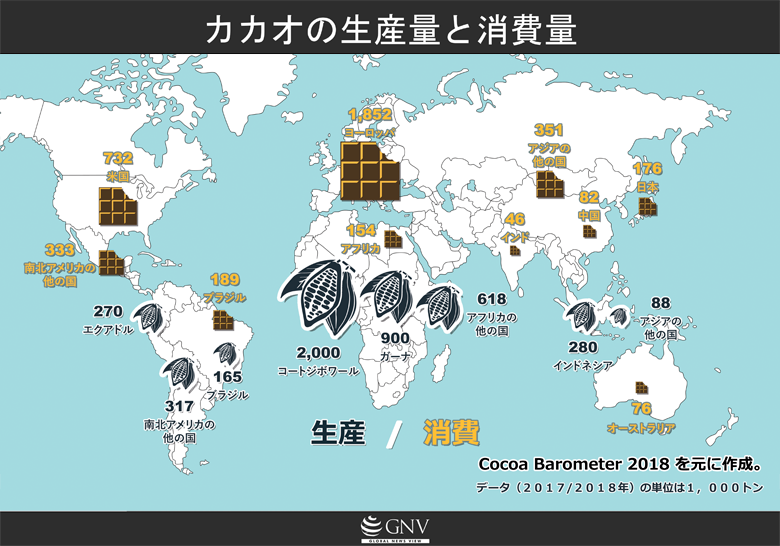

It is hard to say that the sense of happiness enjoyed by those savoring chocolate is shared by the producers of cocoa beans. The reality seen in the statistics is beyond imagination. While 60% of the world’s cocoa beans are produced in just two countries—Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana—a 2018 study conducted in Côte d’Ivoire, the largest producer, found that only 7% of producers in the country were earning a living income (Note 1), while 58% were living in extreme poverty (Note 2). The situation is not much different in neighboring Ghana.

Beyond poverty, child labor is also a serious concern. According to a 2015 study, as many as 2.12 million children were involved in cocoa production in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana alone, a 21% increase from five years earlier. It is also estimated that 96% of those children are exposed to hazards in the course of the work. Similarly, child labor on cocoa farms in Brazil has been highlighted as a major problem. The pervasiveness of child labor is closely linked to extreme poverty. Ninety percent of the world’s cocoa is produced on smallholder farms, and farms in poverty are forced to mobilize their own children as labor. Moreover, it is far from rare for children to be separated from their families due to poverty and other reasons and become caught up in human trafficking or forced labor cases.

Manufacturers and their “measures”

From 2016 to 2017, international prices for cocoa beans plunged, and the incomes of producers—already low—fell even further. Among the reasons were global oversupply due to bumper harvests in West Africa and speculative behavior by investors. In any case, as the cost of raw materials dropped, profits surged for chocolate manufacturers. Although market prices for cocoa beans are fluid depending on supply and demand, the power imbalance between manufacturers and producers heavily influences the setting of prices that are too low. Furthermore, when market prices rise, manufacturers raise retail prices, but when they fall, prices are slow to come down and profits increase—this is the basic mechanism. In other words, it is mainly cocoa producers—already in poverty—who bear the risk.

Sun-drying cocoa beans (Photo: International Institute of Tropical Agriculture / Flickr [ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

The top five manufacturers (Mars, Ferrero, Mondelez, Meiji, Nestlé) account for 60% of global chocolate sales. As the harsh realities in producing regions became known, manufacturers targeted by criticism announced “measures” one after another. For example, Mars announced that it would take into account producers’ incomes and the environment and ensure that 100% of its cocoa is free of child labor by 2025. Meiji, without setting specific targets, posts vague language on its website such as “We will strive to ensure appropriate working environments that respect human rights (including monitoring child labor and forced labor),” while also claiming to be “supporting cocoa farmers” and “contributing” to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, words have not been matched by action, and, as the statistics above show, the situation cannot be said to be improving. Manufacturers avoid systems such as fair trade certification that guarantee a minimum price for producers, or apply them only to a tiny portion of their products, and the share has stagnated. As a result, even when producers incur costs to produce cocoa beans worthy of fair trade certification, many cannot be sold as fair trade products and must be sold on cheaper markets. Moreover, even with fair trade certification, in many cases the system is not actually “fair.” The standards for fair trade certification are lax, and both the minimum price and the premium (incentive payment) are low; not a few producers remain in poverty despite producing fair trade certified cocoa beans. Even if fair trade certified cocoa beans—still not widespread among consumers—were to reach 100% of the market, that would be only a first step toward improving the status quo.

Producer removing cocoa beans, Colombia (Photo: USAID / Flickr [ CC BY-NC 2.0])

Reporting that fails to show chocolate’s reality

So how does Japan’s mass media view chocolate and cocoa? Is the harsh reality facing producers, as described above, being reported?

As a case study, we collected and analyzed 10 years’ worth (2009–2018) of articles (Note 3) on chocolate and cocoa in the Yomiuri Shimbun. The total number of articles was 363, averaging about three per month. However, when domestic reporting was excluded to focus on international coverage, only 22 articles (6%) remained—about two per year. Reporting on chocolate and cocoa appears to be viewed almost entirely from a domestic perspective.

What was the breakdown of those 22 articles on the world and chocolate? Nearly half—nine articles—were about chocolate shops, workshops, artisans, and products, including the “Umai!” series introducing chocolate in London and Geneva. The next most common, five articles, were about charity, but not related to production; they were introductions of campaigns that sold chocolate to raise funds for a hospital in Iraq and a school in India. Other appearances of chocolate were in articles on corporate acquisitions or on the Japan–EU Economic Partnership Agreement.

By contrast, cocoa-producing regions appeared in only two articles, both in the context of problems affecting supply to Japan—in other words, from the perspective of Japanese corporate gains and losses. One was about political problems in Côte d’Ivoire, and the other about a poor harvest in Ghana. Over the 10-year period, there was not a single report on conditions in producing regions or on poverty, child labor, forced labor, unfair trade, and related issues.

Workers gathering cocoa beans, Côte d’Ivoire (Photo: Nestlé / Flickr [ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

“Fair trade” as “support”?

Even outside international reporting, there were other stories linking the world with chocolate and cocoa. These were mainly treated as domestic reporting and dealt with charity and fair trade.

Searching, regardless of domestic or international, for the words “support” or “fair trade” within articles about chocolate and cocoa yielded 22 pieces over 10 years. Of these, 21 were not news articles but promotions of events or activities by NPOs and students. Looking at their content, 11 were about “charity chocolate” for refugees, hospitals, schools, and the like. The remaining 11 introduced “fair trade” chocolate, eight of which also used the word “support.” In some cases, even when explaining fair trade, the articles wrote as if fair trade itself were “support.” Titles for articles about fair trade chocolate prominently included phrases such as “Chocolate to support developing countries” (February 8, 2011) and “Supporting children in cacao-producing countries” (February 10, 2011).

However, fair trade is not “support” for “underprivileged children,” nor is it “social contribution” or “international contribution.” Fair trade refers to fair or equitable trade. It recognizes that developing countries and their producers have historically been in a weak position, forced to sell agricultural products and mineral resources at unfairly low prices, and advocates purchasing at fair prices. There is also an organization that sets criteria (Note 4) to determine whether trade is fair and issues fair trade certification for products that meet those conditions. Thus, fair trade is simply about stopping the exploitation of producers and purchasing products at fair prices—something that ought to be taken for granted—and it is not charity.

Moreover, the fair trade system still has many problems, and as noted earlier, even with fair trade certification, prices are not necessarily set at a fair level that allows people to live without hardship; in many cases, it is hardly “fair.” Nevertheless, in the limited reporting on fair trade chocolate, fair trade is presented as if it were “support” or “social contribution,” reinforcing readers’ misconceptions. At the same time, there is no coverage at all of the extreme poverty caused by unfair chocolate—which occupies an overwhelming share of the market—and the industry behind it, leaving readers’ and consumers’ perceptions far removed from reality.

Family heading to a cocoa farm, Solomon Islands (Photo: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade / Flickr [ CC BY 2.0])

The problems surrounding cocoa bean production remain significant. Neither the level of extreme poverty nor the number of children involved in child labor is decreasing; in some cases they are increasing. At the root is the excessively low price of cocoa beans, and the vast majority of producers earn incomes below the extreme poverty line. Fair trade can be one measure, but its share and penetration are far too small. Moreover, the current fair trade system falls far short of solving the problem. On top of that, Japan’s mass media—which should be responsible for conveying the situation—show little inclination to address the issue itself. Even the limited reporting views matters only from the perspectives of chocolate consumers and companies/organizations, creating an image that “support” for producers is advancing.

“Overcoming poverty is not a task of charity, it is an act of justice.” These are words left by former South African President Nelson Mandela (Note 5). Facing the grave issues surrounding chocolate is not a matter of “charity,” but of “justice.”

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Graphics: Kamil Hamidov

Note 1: A living income is estimated at US$7,318 per year in Côte d’Ivoire, which is by no means a high amount.

Note 2: Extreme poverty refers to living on an income of US$1.90 or less per day, as defined by the World Bank.

Note 3: We searched Yomiuri Shimbun headlines (morning/evening editions, national and Tokyo regional editions) that contained the words “chocolate,” “choco,” or “cacao,” and then calculated the totals after excluding items unrelated to chocolate or cocoa beans.

Note 4: Among the criteria set by Fairtrade International, the “Fairtrade Minimum Price” and the “Fairtrade Premium (incentive payment)”—used for development activities such as infrastructure in producing regions—are notable features.

Note 5: The philosopher St. Augustine, who lived 1,600 years ago, expressed a similar sentiment (“In the absence of justice, charitable acts are no substitute.”).

We also share on social media!

Follow us here ↓

非常に興味深いテーマで面白かったです。

フェアトレード商品にはコーヒーや紅茶、チョコレートなどが多く見られる印象なのですが、それはこれらの製品がその生産の背景にこのような問題を多く抱えているからという理由もあるのでしょうか

ありがとうございます。

チョコレートや紅茶・コーヒーの生産過程における搾取が特にひどいわけではなく、

どんなモノであろうと、問題は生産者の立場が弱く、メーカーや商社の立場が強いという不均衡から生まれているので、

同じような搾取と貧困の助長が見られると思います。

綿花やバナナも有名だが、たばこ、石材、砂、電化製品に入っている鉱物資源(Fairphoneの試みを参照)なども、いっぱいあります。

チョコレート・紅茶・コーヒーは豆・葉っぱなど、収穫された元の状態に近い商品がわかりやすいというところがひとつポイントでしょう。

今の時期、どこのデパートやお店でもチョコレートで溢れていますがこの中の何人が果たしてカカオ農家の現実を知っているのだろうかと最近考えます。価格が上がったのは決して労働する人の待遇が良くなったからではないのですね。透明性が必要な業界の1つといえますね。

そうですね。「フェアトレード」のラベルで価格があがったとしても、実際のところ、労働者の手にどれほど渡り、どれほど生活がよくなっているのか・・これがフェアトレードの大きな課題だというのが明らかです。「フェアトレード」より、「ちょっとましかもしれないトレード」のほうがふさわしいかもしれません。

透明性がまさに大きな第一歩になるでしょう。

「アンフェアトレード」が異常な状態であるはずなのに、フェアトレードが当然のことと認識されていないことは腹立たしいです。せめて、アンフェアなチョコレートを買うときに、これは労働搾取への一票だという認識が人々のあいだに広まればいいなと思います。

チョコレートが大好きなだけに、農家の助けになっているというような売り文句に踊らされていたことにショックです。私たち消費者が声をあげないと企業の姿勢は変わらないでしょうね。

「同国で不自由なく生活できる収入を得ている生産者はたった7%にとどまり、58%は極度の貧困状態にある」という事実に非常に驚きました。グローバル化が進む世の中だからこそ、私たちの身の回りにあるものは、世界のあらゆる問題にも繋がっている可能性があるということを忘れてはならないと思いました。

フェアトレードの認知度はずいぶん高くなったと感じますが、実態は中身の伴わない形だけのものだったということに、騙されたままチョコレートを食べている我々が情けないです。人件費を最低限まで削りコストや利益しか重視しない企業には未来がないと思っています。そうありますように。

「貧困の克服とは、慈善行為ではない。それは正義の行為だ」という言葉はとても心に響きました。店頭の商品を買うことが生産者を搾取していることにつながるという現状のシステムが痛ましいです。

興味深く拝見しました。

私はチョコレートが好きです。

ベーシックな板状のものだけでも、、

明治や森永、ロッテの板チョコレートは50gで120円程度

イオントップバリュの産地銘柄板チョコは85gで250円程度

ピープルツリーのフェアトレードチョコはフレーバーが入っていますが、50gで350円程度

ビートゥバーの専門店では50g1500円程度

海外から輸入されるデザインの素敵な板チョコも1000円〜2000円

と大きな幅があります。

「貧困の克服とは、慈善行為ではない。それは正義の行為だ」

おそらく生産の過程にかかわっているビジネスマンたちはだれもが搾取してやろう!

とはおもっていないでしょう。

日常的にチョコ食べる人もいれば、そうでない人もいますが、

一人一人が生産者も消費者も、たとえばこれらが一律に300円とか値上げになっても受け入れられる?と思えば

フェアトレードの現実を批判するのみでなく、改善できるのではないでしょうか?

日本は特にデフレの国、自国の農産者にあっても同様の問題がありますが、

消費者にとって良質で安価な食品が手に入ることはすばらしいことでもあります。

また全ての子供は売られたりするべきではないけれど、

親元で親の仕事を手伝い育つことは悪いことではないとおもいます。

労働にみあった生活できる収入を得ていけるような仕組みを考える力が

生産者の中からも生まれてほしいと願っています。

そうならなければ、将来消費者の口に入る食物もずっとすくなくなってしまうかもしれません。

コーヒーも単価が安いですが、立地の良いカフェでも販売者が一杯の飲み物のために得られる利益は

チョコレートよりずっと多いのかもしれませんね。

産地においてはいかがでしょう。

英国のみならず王侯貴族たちの負の遺産。

やつらを潤すために歴史上大半の人類が犠牲になる。そんな愚かな価値観が未だ続いているからやるせない。民主主義とは名ばかりで世界はほどよく貴族社会だ。嘆かわしいのはそれに気づかない民衆。飼い慣らされている。1日働いても1000円に満たないカカオ農家の人は東京で3000円の板チョコが売られてるのを知らない。狂った世界だ。世直しを誰が?少なくとも欧州や米国ではない。ロシアや中国かもしれないと思えてくる。

黙れよ共産主義野郎。