In 2018, the small island nation in the South Pacific quietly entered an important year. Four years after the 2014 election, the Republic of Fiji will hold its second general election since the return to civilian rule.

Among Pacific countries such as Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, and Tonga, Fiji stands out for its economic development. Its population is 900,000, and while one-third of its economy is supported by sugar exports, the next-largest sector, tourism, has been the engine of growth. Thanks to its warm year-round climate and crystal-clear seas, it is even called “ Home to happiness ” in the tourism sector, drawing people from around the world seeking a peaceful vacation. However, it was only a generation ago that Fiji experienced a “not so peaceful” history of four coups. The story goes back to the colonial era.

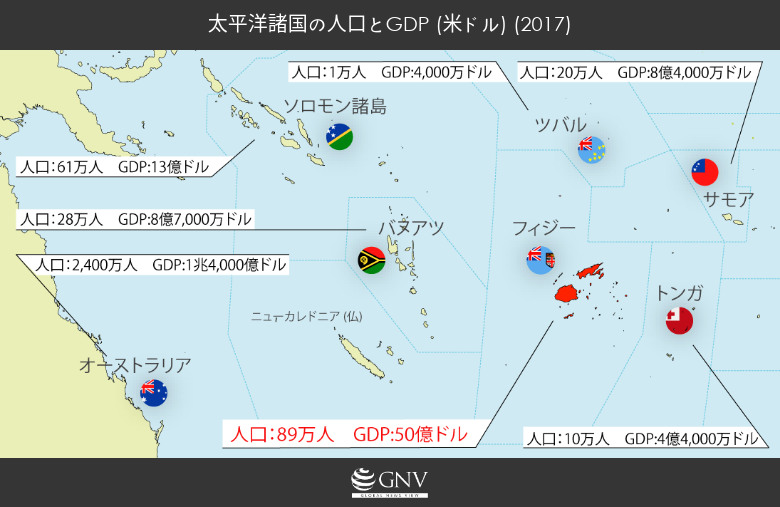

Created based on IMF data

Plantation workers brought from India

Today, Fiji is a multiethnic state composed of roughly 60% indigenous Fijians (iTaukei) and 40% Indo-Fijians (2007), along with many other ethnic groups. (*1) Indo-Fijians were brought from India during British rule to work on sugarcane plantations, and over 61,000 people moved between 1879 and 1916. At independence in 1970, they outnumbered the iTaukei population, and it was in fact Indo-Fijians who drove the economy. However, political control, backed by the former colonial power, was held by iTaukei leaders. The separation of politics and the economy—and the lack of dialogue between these two groups, which at the time were routinely set apart—fueled conflict and political instability in Fiji.

When the constitution was drafted at independence, Indo-Fijians sought political participation free from racial discrimination, but the inequality of the final document was obvious. Parliament was bicameral: while the lower house had seats allocated by ethnicity and decided by vote, in the upper house traditional iTaukei political leaders who governed villages appointed more than one-third of the seats. As for land ownership, over 80% of the national territory was designated inalienable communal land of the iTaukei, while Indo-Fijian land ownership was restricted.

People passing through the capital, Suva. A mix of many ethnicities. (2012) (Photo: kyle post/Flickr [ CC BY 2.0])

The beginning of the coups

In 1987, the first coup took place. The trigger was the April general election that year, in which the Alliance Party, which had maintained a majority, was replaced by a coalition of the National Federation Party, supported by Indo-Fijians, and the Fiji Labour Party. After election results that saw Indo-Fijian ministers occupy half of Parliament, Lt. Col. Sitiveni Rabuka of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces seized power in two coups, withdrew from the Commonwealth, and transitioned to a republic. The 1970 constitution was suspended, and a revised constitution with the paramount aim of protecting iTaukei traditions and interests was promulgated. Of the 70 lower house seats, iTaukei were allocated a majority of 37, and Indo-Fijians 27. The upper house also used racial allocations, but Indo-Fijians were excluded; based on the advice of village leaders, 24 of the 34 seats were appointed by the president. In addition, the office of prime minister was restricted to iTaukei. The government’s ethnic nationalism instilled a sense of crisis among Indo-Fijian residents and was enough to drive many abroad: over the nine years from 1987, 75,000 Indo-Fijians left the country.

However, the regime soon found it necessary to change course. Having abandoned democratic rule, Fiji faced criticism from the United Nations and neighboring countries, and the outflow of Indo-Fijians—many of whom held skill-based jobs—hollowed out the economy and society. Recognizing that ethnic nationalism also harmed the iTaukei, and reassured by the Indo-Fijian exodus that pushed the iTaukei population above 50%, the government sought to rebuild by promulgating a new constitution amid a mood of ethnic reconciliation.

The dream of rebuilding fades

What looked like a new step for Fiji as a nation crumbled all too quickly. In the 1999 general election, the year after the new constitution was promulgated, Labour Party leader Mahendra Chaudhry was elected as the first Indo-Fijian prime minister, rekindling fears among some iTaukei. In 2000, businessman George Speight led an armed group to occupy Parliament and took Chaudhry hostage for 56 days. Power passed to iTaukei leader Laisenia Qarase, and Fiji once again followed a path in which iTaukei-led coups countered democratic politics.

A restaurant burned in the riots that followed the coup (Suva, 2000) (Photo: Merbabu/Wikipedia Commons [ CC BY-SA 3.0])

There is also a theory that Speight’s true motive in leading the coup was that the Chaudhry government canceled contracts with two timber companies he represented. Whether Speight acted out of ethnic-nationalist sentiment or for economic reasons, the Qarase administration was clouded by a lack of transparency regarding the coup and business, with rumors that Qarase had pulled strings behind the scenes. Qarase became prime minister in the 2001 general election and was re-elected in June 2006, but in December that year he was ousted in a coup by military commander Bainimarama, who denounced the government’s lack of transparency. Having carried out this bloodless coup, Bainimarama was appointed prime minister in January the following year.

The Bainimarama era

The gaze from neighboring countries toward Fiji, which had abandoned democratic politics, was severe. Having ignored the democratization roadmap presented by the PIF (Pacific Islands Forum), Fiji was stripped of its PIF membership. Although it had rejoined the Commonwealth in 1997, it was also expelled for failing to comply with the UK’s required democratization process. As a result, relations with nearby Australia and New Zealand cooled, and Fiji pivoted toward strengthening ties with Russia, China, ASEAN, and Arab countries.

Prime Minister Bainimarama (right) shaking hands with Russian Prime Minister Medvedev (at the time) (Moscow, 2013) (Photo: The Russian Government )

Domestically, there was one-party rule with the military exerting control over the public. Media freedom was strictly limited, and the military monitored broadcasters. Some public intellectuals who criticized the regime were expelled from the country. In 2009, the courts ruled that the then-interim government was illegal and unconstitutional, ordering the president to appoint a new interim prime minister and interim government. In response, Bainimarama was again appointed prime minister by the president, for the next five years, and announced that general elections would be held by 2014.

In 2013, the year before the election, a new constitution, drafted by the government and completed after soliciting public input, was promulgated. By specifying protections for land owned by iTaukei and minority groups, it signaled consideration for them; at the same time, it incorporated both the Fijian and Hindi languages into the primary education curriculum, aiming to create a national identity that transcends ethnicity. Parliament was changed from a bicameral body to a unicameral chamber of 50 seats; ethnic distinctions were eliminated, and voters—both iTaukei and Indo-Fijian—could cast an equal vote.

And in 2014, the first general election in eight years was held, and Bainimarama was returned to power. It was Fiji’s restart as a democratic state through the country’s first election without racial distinctions.

Toward the second election after the return to civilian rule

Since the 2014 election, has Fiji truly become a democracy? There has been much criticism. Some argue that strict candidacy requirements shackled other parties and that the election was held knowing Bainimarama would win. Although government monitoring of the media officially ended in 2012, journalists still do not enjoy full freedom of expression, including criticism of the government, and intellectuals expelled before the election have still not been allowed to return home.

That said, although Fiji had only just restarted as a democracy, it is also true that since the election the country has increased its presence on the world stage. Relations with Australia and New Zealand have been restored, and it has rejoined the PIF. Fiji’s permanent representative Peter Thomson was elected president of the UN General Assembly; at the 2015 COP21 (UN climate conference), Fiji became the first country in the world to ratify the Paris Agreement, and two years later COP23 was hosted by Fiji. From the standpoint of a Pacific nation directly affected by climate change, Fiji has acted as a spokesperson leading the world toward progress on environmental issues.

Prime Minister Bainimarama speaking at COP23 (Bonn, 2017) (Photo: UNclimatechange /Flickr [ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0])

There has been no coup for the past 11 years. If this year’s general election proceeds peacefully, it will demonstrate that democracy in Fiji is at least taking root formally, but how will the public evaluate the past four years? In a public opinion survey conducted this February, Bainimarama’s FijiFirst Party polled at 32%, followed by the iTaukei Social Democratic Liberal Party at 22%, and the Indo-Fijian National Federation Party at 3%. However, at that time 34% of respondents were undecided about which party to vote for, and their choices will determine the outcome. The election schedule is expected to be announced soon. In the election campaign that will now kick into full gear, alongside ethnic issues, development challenges such as education and poverty reduction are likely to be key issues. Keep an eye on Fiji as it strives to overcome the difficulties of being a multiethnic nation.

A boat carrying tourists from Port Denarau to the outer islands (Photo: Miho Kono)

*1: Hereafter, indigenous Fijians are referred to as “iTaukei,” and Fijians of Indian descent as “Indo-Fijians.”

Writer: Miho Kono

Graphics: Miho Kono

また民族対立が再燃し、クーデターで憲法が変えられることで、人種差別が深刻化しませんように…

しかし、十数年前にクーデターで政権をとった人が未だに権力の座に居残っている・・と考えると、不安はちょっと残りますね。

フィジーが行っている環境問題への対策を知りたいです

人種の問題が起きると、混血の人の問題が出てくると思うのですが、フィジーとしてはそのような問題はあるのでしょうか?