World Heritage sites, regarded as the common heritage of humanity, are found across the globe. What do they represent to people around the world, and how are their significance and value communicated? For many people, information about World Heritage is often obtained as part of tourism, via guidebooks and websites. TV programs that introduce World Heritage are also broadcast weekly. They also appear frequently in the news through media such as newspapers. This article explores, from the perspective of routine news coverage, how information about World Heritage outside Japan is conveyed.

Preah Vihear Temple in Cambodia. (Photo: Chiara Abbate [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

World Heritage and its issues

World Heritage is defined by UNESCO as “irreplaceable treasures created by the formation of the Earth and human history, passed down from the past to the present.” World Heritage is divided into “cultural heritage” and “natural heritage,” with some sites recognized for both values as “mixed heritage.” Currently, 1,073 World Heritage sites are inscribed, the vast majority (832) being cultural heritage (206 natural heritage, 35 mixed heritage).

For inscription as World Heritage, each country that has joined the “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage” (commonly called the “World Heritage Convention”※1) recommends candidates, and the World Heritage Committee, composed of representatives from 21 countries, decides on the inscription. However, various problems with this process have been pointed out. For example, the regional distribution of inscriptions is skewed, with a concentration in Europe. There is also a trend in which the longer a country serves on the Committee, the more of its nominations are inscribed.

Meeting of the World Heritage Committee held in Germany (2015). (Photo: Matthias Ripp [CC BY 2.0])

Furthermore, beyond the selection and inscription process, questions have been raised about the very existence of World Heritage. For example, although World Heritage is considered a common asset of humanity, in practice it is often used to assert national prestige and pride, and as a result can stoke nationalism. The historical significance and ownership of heritage can also be contested between states or ethnic groups, and can even become one cause of armed conflict.

In addition, 54 World Heritage sites are considered to be in a critical condition because their value is threatened for various reasons. One such reason is armed conflict. Sometimes parties to a conflict intentionally try to destroy sites; in other cases, they suffer indirect damage through fighting. On the other hand, there is also damage from tourism. When a site is inscribed, a tourism rush can occur and, although inscription is meant to protect, conservation can become more difficult as a result. At the same time, without attention to World Heritage, it is difficult to secure funding and personnel for conservation—a dilemma that persists today.

Coverage of World Heritage (by country)

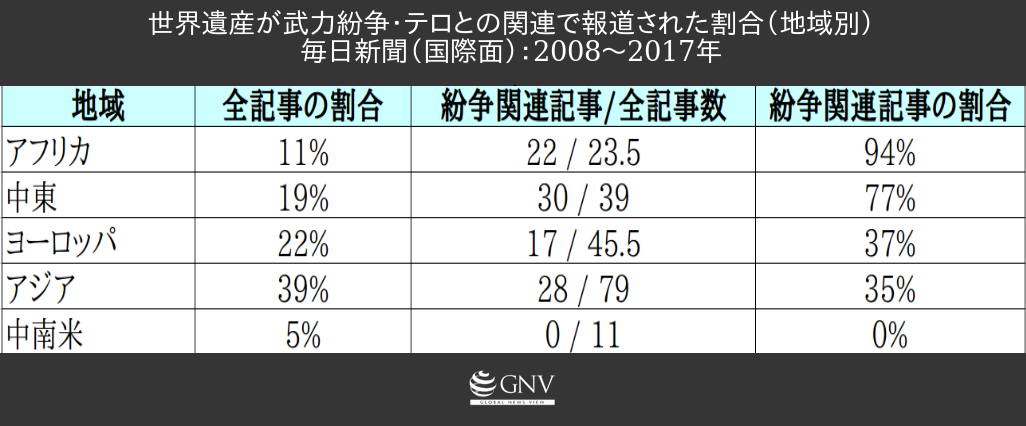

So how is World Heritage—an entity with complex issues—covered in the news? To examine trends in international reporting, we searched for articles containing the term “世界遺産” (“World Heritage”) on the international pages of the Mainichi Shimbun over the 10 years from 2008 to 2017. The majority (80%) of the 205 relevant articles were about Asia (58%, of which 19% concerned the Middle East) and Europe (22%). The remaining articles were 11% about Africa, 6% about the Americas (with 3% other/unspecified). This can be said to reflect, to some extent, the usual regional bias in the international reporting of Japanese newspapers.

The chart above shows the top 10 countries most reported on in connection with World Heritage during the same period. The most covered were World Heritage in Cambodia and Thailand, specifically reports about the Preah Vihear Temple located along their border. Built in the 9th century by the Khmer Empire, sovereignty over the temple and its territory is disputed by both countries, but according to an International Court of Justice ruling, the temple itself is on the Cambodian side. In 2008, its inscription as World Heritage triggered military clashes, and the two countries’ forces have skirmished several times since.

There was also extensive coverage of World Heritage in Syria. This was mainly about the ancient ruins of Palmyra, partially destroyed during occupation by IS (Islamic State), and the city of Aleppo, which suffered damage through the conflict between the Syrian government and opposition forces. In Iraq too, coverage centered on World Heritage threatened by conflict with IS. More than half (55%) of reports on World Heritage in Africa were about Mali. The city of Timbuktu, which flourished in the 16th century and includes historic mosques, shrines, and libraries, was featured, but the only coverage was about the partial destruction of heritage when rebels occupied the city in 2012.

A mosque in Timbuktu, Mali. (Photo: UN Photo/Marco Dormino [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

There was also significant coverage of Italy (1st) and Spain (3rd), countries with many inscribed properties. In Italy, reports covered heritage damaged by an earthquake in Bologna in the north and various issues surrounding the Colosseum. In Spain, World Heritage also drew attention in relation to the Catalan independence movement and terrorism. However, having many World Heritage sites does not necessarily translate into coverage. China ranks second in the number of World Heritage sites, but coverage in the Mainichi was almost nonexistent. By contrast, all reporting on Nepal’s World Heritage concerned damage from the 2015 earthquake.

Furthermore, despite being on the international pages, many articles covered World Heritage related to Japan. These were mainly reported in connection with historical and territorial issues with neighboring countries, but there were also reports on domestic World Heritage with no international aspect other than their inscription.

Armed conflict and World Heritage

As has become clear, when World Heritage appears in international reporting, it is often accompanied by armed conflict. Over 10 years on the international pages of the Mainichi Shimbun, about half (48%) of articles concerning World Heritage were connected to violent events such as armed conflict or terrorism. Of the five most-covered countries, four (Cambodia/Thailand, Syria, Mali, Iraq) were primarily the subject of coverage because of conflict. Incidentally, in the New York Times, looking at 10 years of coverage in the same way, reports on World Heritage involving armed conflict accounted for 38% of the total, lower than in the Mainichi.

However, as the chart above shows, there are major differences by region. For Asia, 35% of World Heritage coverage was in connection with armed conflict, but in Africa, conversely, only 6% of coverage was unrelated to conflict. In other words, absent armed conflict, Africa’s World Heritage is rarely a subject of coverage. Although the African continent has 138 World Heritage sites, more than half of the Mainichi’s 10 years of Africa-related articles concerned just one of them (Timbuktu in Mali, which was partly destroyed). For Côte d’Ivoire and Egypt as well, World Heritage was introduced in the context of terror attacks. Newspapers station few correspondents in Africa, and as only 2–3% of international coverage typically concerns Africa, it is hardly surprising that unless there is a major violent incident, it does not become a subject of reporting.

Moreover, the current situation in which World Heritage is covered by the media only in connection with armed conflict is accompanied by another problem. As with the ruins of Timbuktu and Palmyra, armed groups have targeted World Heritage itself and tried to destroy it intentionally. Going further back, in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, the giant Buddha statues destroyed by the Taliban in 2001 are a representative example. However, in armed conflict, not only the heritage but also the people living around it are targeted and harmed. When Palmyra and Bamiyan were seized by armed groups, many lives were lost not only in fighting but also through massacres; fear drove many to flee, and refugees poured out of each area. Yet media attention focused on the ruins rather than on people.

Demining at the ruins of Palmyra, Syria. (Photo: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation [CC BY 4.0])

For example, in February 2001, when Bamiyan was recaptured by the Taliban, there were two months during which the Mainichi Shimbun reported only on the plan and execution to destroy the Buddha statues, without any mention of human casualties. Around this destruction, the Taliban pointed out that although many people in Afghanistan were dying of hunger, the world cared only about the statues, citing this as one reason for the destruction. While it was an illogical attempt at justification, the world’s attention certainly was not directed at the people suffering in the conflict. In May 2015, before and during IS’s seizure of Palmyra in Syria, the Mainichi ran just one article with the headline “IS closes in on World Heritage: Palmyra at risk of destruction.” The focus on human casualties came only a week after the recapture. Voices from residents in Syria asked why ruins were valued more than human life, and journalists themselves have been called out by experts regarding Syria and Yemen.

Of course, protecting ruins during armed conflict is important. It is also possible to raise our voices and take action to prevent harm to both human lives and heritage, and many people are indeed doing so. However, judging from international reporting, such balance is hard to find.

News organizations favor dramatic action and unusual events. Destruction is more likely to be reported than preservation or conservation. Damage to heritage is rarer—and thus more newsworthy—than human suffering in armed conflict. These news values become evident. While it is important to focus on World Heritage placed in peril by armed conflict, it is equally important to focus on the human lives being lost. There is of course a reasonable side to not making World Heritage a subject of reporting when there is no movement or development. However, there are many events that should be covered outside the context of armed conflict. Even in peacetime, without media attention, fundraising necessary for protection and conservation can be difficult. And, as with international reporting in general, severe regional disparities persist in World Heritage reporting. It may be time to reconsider international reporting on World Heritage from multiple angles.

Bamiyan, Afghanistan (autumn). (Photo: Johannes Zielcke [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

※1 Adopted at the 1972 UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) General Conference.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

観光の対象として世界遺産に興味があり調べているうちに、この記事が目に止まりました。

『報道の注目は人間にではなく遺跡にあったのだ』指摘されて確かにその通りだと思いましたが、気もつきませんでした。

多くのヒトは何の疑問もなく報道内容だけを世の中の全体像として受け入れています。

取り上げる対象国に偏りがあるだけでなく、取り上げるシーンも読者受け?を狙い偏りがあることが指摘されており、共感するとともに受け止め側としても反省すべきことも多いと思いました。

今後、ますますこのサイトが盛り上がることを期待しています。