2017 was a year in which long-standing regimes ended in three countries. In January, Gambia’s Jammeh stepped down after his defeat in the presidential election, ending 22 years in power. In September, Angola’s dos Santos announced he would not run in the election, and the presidency changed hands for the first time in 38 years. In November, Zimbabwe’s Mugabe resigned from the presidency following a coup. The 93-year-old world’s oldest head of state brought 37 years of rule to a close. The Zimbabwe case, in particular, was widely reported in Japan and is likely familiar to many. So, we compared the volume of reporting—by article count—on the 2017 resignations in Gambia, Angola, and Zimbabwe across Japan’s three major national dailies: Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi. The results were: Gambia 13 articles, Angola 1 article, Zimbabwe 77 articles. Despite the similar nature of the events—long-term regimes changing—there was a large disparity in coverage among the three countries. Incidentally, the number of articles about Zimbabwe the year before was just seven. This indicates that, although Zimbabwe is usually scarcely covered, its resignation in 2017 drew exceptional attention.

Three presidents at a press conference (2013). South Africa’s Zuma (left), who was forced to resign in February 2018; Angola’s dos Santos (center), who stepped down from the presidency in 2017; and the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Kabila (right), who remained in office even after his term expired. (Photo: GovernmentZA/Flickr [CC BY-ND 2.0])

Although three long-standing regimes ended in 2017, many countries around the world still have governments that have been in power for over 20 years. This article focuses on coverage of such long-running regimes and authoritarian states to analyze Japan’s international reporting.

What is an authoritarian regime?

First, let’s explain what we mean here by an authoritarian state. In authoritarian regimes—whether military rule, one-party rule, personalist rule, or monarchies—power is concentrated in the hands of a small number of people. In such states, citizens’ political participation may be restricted, there may be no separation of powers, and wealth may be distributed only to a privileged few with little provision of public goods. Even so, elections may be held in authoritarian states. However, because the methods and processes are unfair, they cannot be called democratic elections. For example, regimes may attach unreasonable pretexts to ban opposition candidates or their campaigns, inflate voter rolls or ballot counts to secure votes, control state media to favor the incumbent, or falsify the figures in election results, among other tactics. Some leaders also use seemingly democratic tools such as elections and referendums to expand their own power. In other words, some countries look democratic on the surface but are authoritarian in substance.

As a criterion for determining whether a state is authoritarian, we use the Democracy Index ranking published by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The index covers 167 countries worldwide. Each country receives scores in five categories and is classified into one of four groups, from highest to lowest score: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian regimes. In the analysis that follows, we focus on countries in the authoritarian category.

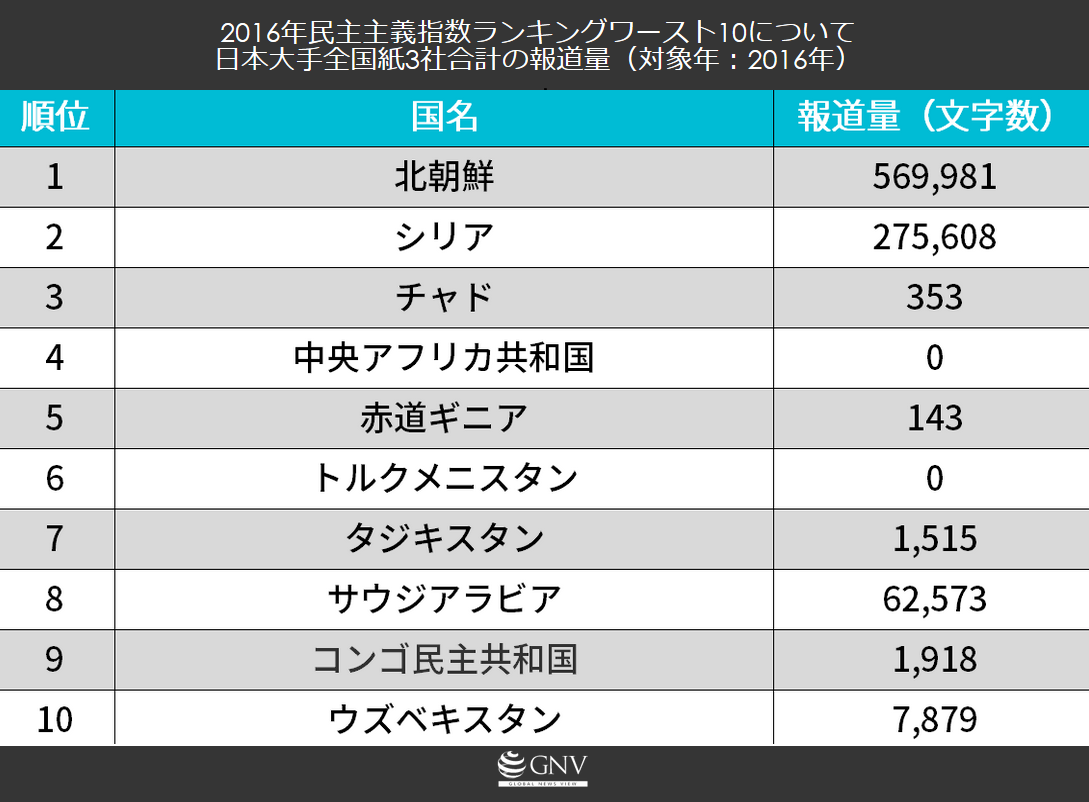

Coverage volume for the bottom 10 in the Democracy Index

Let’s first look at the volume of Japanese reporting on the 10 countries at the bottom of the Democracy Index rankings. We use the 2016 Democracy Index and data collected from the 2016 morning editions of Japan’s three major national dailies (Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi). Through this analysis, we aim to see how much Japanese media report on highly authoritarian countries and from what angles they cover them.

The table above lists countries from the lowest rankings upward and compares coverage by character count. As you can see, coverage of North Korea and Syria is overwhelmingly high. In fact, in international reporting overall in 2016, North Korea was the 4th most reported country and Syria the 7th. Much of the coverage of North Korea focused on missiles, nuclear issues, and abductees. Reporting on Syria largely concerned the Islamic State (IS) and the conflict. The next most-covered country was Saudi Arabia, with prominent stories about the severing of diplomatic relations with Iran and oil.

The other countries saw less than 10,000 characters of coverage over the year. So what exactly was reported about each? In Uzbekistan, most stories were about President Karimov being hospitalized in August 2016 and his death the following September. Karimov had been in office for 27 years until his death, during which the government committed widespread human rights violations. In December 2016, the first transfer of power took place.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, news reported that 17 people were killed in anti-government protests in September. The protests were held in response to President Joseph Kabila’s attempt to unjustly extend his term. The DRC also had the world’s highest number of internally displaced persons due to conflict in 2016, with about 920,000 people displaced.

Regarding Tajikistan, the abolition of presidential term limits was reported. In May, a referendum on constitutional amendments to make the president’s tenure indefinite was held and passed by a wide margin. President Rahmon marked his 24th year in office in 2018. The 2016 constitutional changes also lowered the minimum age to run for president from 35 to 30, said to be intended to allow Rahmon’s son to run in the next presidential election.

The remaining four countries were scarcely covered. As for Chad, there was an article reporting that former President Habré was sentenced to life imprisonment by a court in Senegal, where he had been living in exile, for crimes against humanity. In Equatorial Guinea, it was reported that the president won reelection for the fifth time, while the Central African Republic was not covered despite holding a presidential election. Notably, the Central African Republic—plagued by instability and ongoing armed conflict—elected a president through an election for the first time in a while, yet none of the papers mentioned it. Turkmenistan has been under the strongman rule of President Berdymukhamedov since 2007, but there was no coverage of Turkmenistan in 2016.

From this, even when we limit analysis to authoritarian states, we can see that only a subset of countries is frequently reported on, and that African countries are less likely to be covered. On the other hand, even in countries with little coverage, we found that the few stories that did appear sometimes touched on news related to their political systems. However, because this survey focuses on authoritarian countries, it does not tell us whether authoritarianism itself draws attention. Next, then, let’s focus on leaders—the faces of authoritarian states.

Coverage of the top 10 currently long-serving leaders

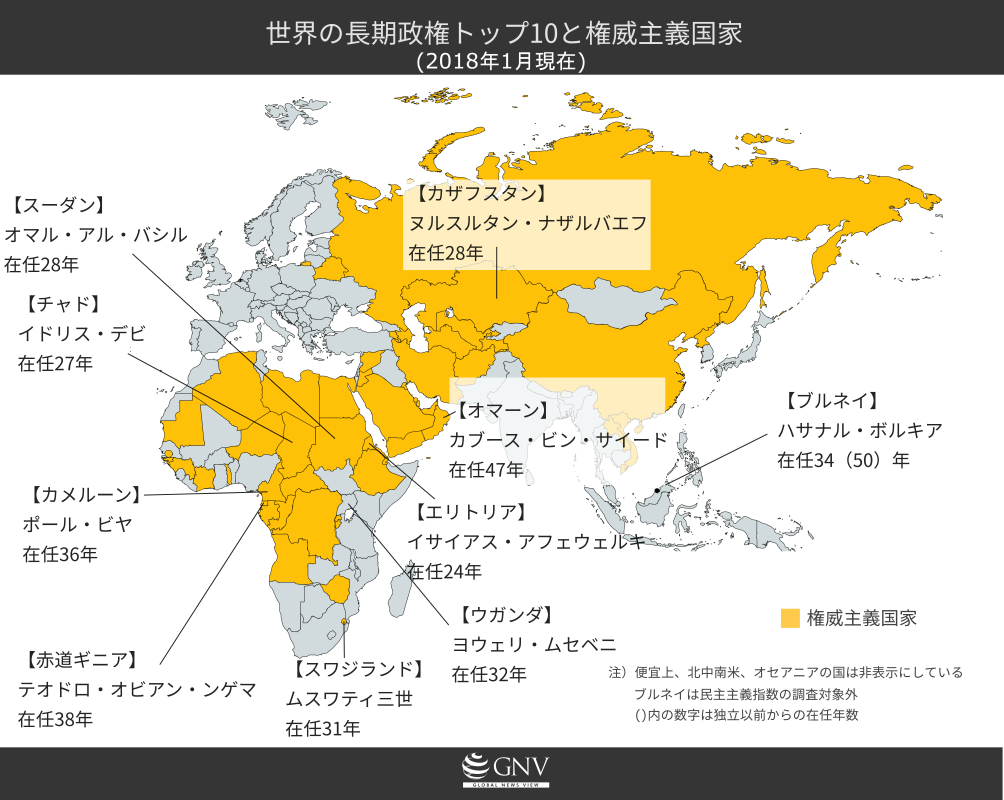

There are as many as 13 leaders in the world who have ruled their countries for over 20 years. (Note 1) The forms of rule include presidential systems and monarchies. The figure below shows the 10 longest-serving leaders. (Note 2)

The longest-serving is Oman’s Sultan Qaboos bin Said. He deposed his father, the reigning sultan, in a 1970 coup and assumed the throne. He also serves as prime minister and foreign minister, holding absolute power over Omani politics. While his rule is authoritarian, he has advanced modernization and infrastructure development and enjoys public support. During the Arab Spring, he swiftly responded to citizens’ demands and calmed protests.

Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah succeeded his father in 1967. At the time, Brunei was a British protectorate with autonomy over internal affairs; it achieved full independence in 1984. Although the system is a constitutional monarchy, parliament was suspended after independence. It was reconvened in 2004, but Bolkiah still controls national governance.

Kazakhstan’s President Nazarbayev has remained in power since independence from the Soviet Union. In 2010, parliament approved extending his term without an election, but the following year an election was held and he was reelected. He has argued that democratization is “a long-term goal, but it should not be rushed because it would undermine stability.”

For more on Africa’s long-serving regimes, see this article.

Next, let’s see how much these 10 countries were covered over the past 20 years. We examined the morning editions of the three major national dailies and measured the character counts of articles whose headlines contained the leader’s name or wording referring to the leader. The results are shown in the graph below.

At a glance, it’s clear that coverage of Sudan’s Bashir and Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev stands out among these 10 countries. Reporting on President Bashir most frequently concerned the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant against him for orchestrating mass killings during the Darfur conflict in the 2000s. For President Nazarbayev, reelection news was prominent. For the other countries as well, election-related coverage could be found. Nevertheless, over a 20-year period, more than half of the leaders drew less than 5,000 characters of coverage across the three papers, equating to fewer than 10 articles. In short, even a long tenure does not translate into increased coverage of the individual leader.

Does authoritarianism become a focus of coverage?

We have examined how authoritarian regimes are covered in Japanese media from two angles: countries and leaders. The analyses indicate a large disparity in coverage across different countries and leaders. However, there is likely little correlation between the degree of authoritarianism and volume of coverage. While North Korea and Syria were heavily reported, this was not so much because they are authoritarian as because they are seen as direct threats to Japan—nuclear and missile issues, conflict, and the like. As for long-standing regimes, the length of tenure does not correlate with coverage volume. Coverage is likely to increase when there is a major incident, especially one that attracts significant attention in the West, as in the case of Sudan’s Bashir, making it more likely to be covered in Japan.

By definition, long-term regimes do not change governments, so dramatic changes are rare. Conversely, the end of a long-standing regime is a major change and would be expected to boost coverage. As noted at the outset, Mugabe’s resignation in Zimbabwe last year was widely reported. However, the other two countries received little coverage. Reasons include the leader’s name recognition and relations with other countries. Mugabe had long antagonized the West and was recognized as a notorious leader. As a result, his resignation was given prominent coverage in the West, which in turn increased coverage in Japan. In other words, for long-entrenched authoritarian states to be reported on in Japan, sensational events that draw international attention are often required. But even in the absence of major incidents, is it acceptable to ignore countries where power and wealth are monopolized and human rights violations occur on a daily basis? We will continue to watch how authoritarian states are covered.

Sultan Qaboos speaking with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry / Muscat, 2013 (Photo: U.S. Department of State/flickr [U.S. Government Works])

[Footnotes]

Note 1: Years are counted from the establishment of the current system. If there is a gap between the first and second terms, only the second term is included.

Note 2: For monarchies, only countries in which the king holds executive power are included. In Iran, the Supreme Leader has the final decision-making authority on state affairs and serves as commander-in-chief, but because the president is the head of the executive branch who implements policy, the Supreme Leader is excluded here.

Writer: Miho Horinouchi

Graphic: Miho Horinouchi

0 Comments