From the era of landlines to the advent of mobile phones and then smartphones, our means of communication have been changing rapidly over the past few decades. Especially since smartphones appeared, they have become not just tools for communication but palm-sized gateways to vast, multifaceted services. You might think the same kind of change is happening everywhere, but that’s not quite the case. Look at Africa: the way mobile has been used there has followed a distinctive path. For example, while electronic money is now spreading in advanced regions, in Africa that shift happened long ago. This article explores how mobile use in Africa has evolved in close step with people’s daily lives—and where it is headed.

People using mobile phones, Uganda (Ken Banks/Flickr) (CC BY 2.0)

No landlines: “mobile-only”

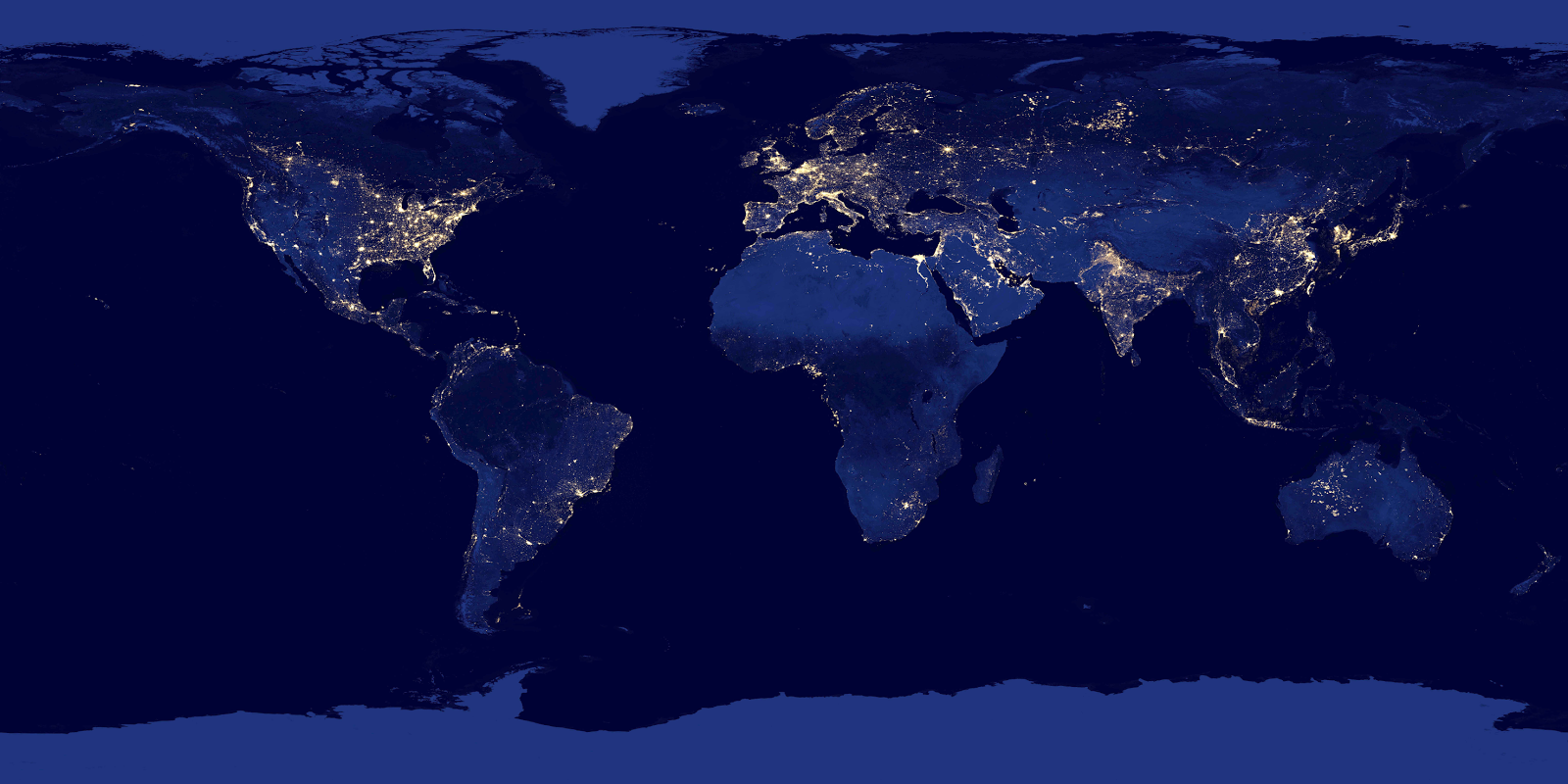

You may have seen a map like the one below: some places are bright at night, others not. In Africa’s vast lands—where many agricultural workers are dispersed and poverty is widespread—bringing electricity to every household is no easy task. In fact, in Sub-Saharan Africa only one in three people uses electricity in daily life, leaving 609 million people without access. In such circumstances, it was never realistic to expect household-wired landlines to spread.

Earth seen from space at night (PROIIP Photo Archive/flickr) (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Thus, starting around the year 2000, mobile phones leapfrogged fixed-line telephony. It’s far easier to erect a single antenna to cover a certain area than to lay a line to every home. And even if your house has no electricity, you can charge your phone at a relative’s or friend’s place that does, or at a neighborhood “charging shop.” Solar-powered charging has also been developed. Feature phones with simple functions spread rapidly, centered on SMS for exchanging messages via phone numbers. But it wasn’t just for texts. A wide variety of services built on SMS took root and transformed daily life. Here are some examples.

Beyond text messaging: services built on mobile phones

- Electronic money

Electronic money has been spreading worldwide in recent years. From 2006 to 2016, the number of mobile money services grew from 7 to 277 globally. Remarkably, half of those launched in Sub-Saharan Africa, and of the 170 million active users worldwide, 100 million are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

A major driver of mobile money in Africa was M-Pesa, a mobile money transfer service launched in Kenya in 2007. It spread explosively, and by 2016 accounts reached 90% of the adult population. This made it possible to move money as easily as sending a text—covering everything from paying utility bills and in-store purchases to remittances to distant relatives or business partners, all via M-Pesa. While other regions moved from cash to credit cards and then to electronic money, Africa—where fewer people had bank accounts—leapt straight to mobile money without going through credit cards. Today, about half of Kenya’s GDP flows through mobile money, with enormous economic impact. One study even found that 2% of Kenyan households moved out of poverty simply because they gained access to M-Pesa.

People using M-Pesa (Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion (IMTFI)/flickr) (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Agriculture

Agriculture remains a pillar of Africa’s economy, with total revenues exceeding US$100 billion. Mobile-powered services are providing multifaceted support to farmers. Many services now deliver necessary information in real time, such as Kenya’s M-Farm and Cameroon’s Agro-Hub, which send SMS alerts about weather and market crop prices and offer platforms for farmers to exchange information freely. There are also services that provide expert advice on crop and livestock health, such as Kenya’s i-cow, Ghana’s Cocoa Link, and Esoko, used in nine countries including Nigeria—each tailored to the dominant industries of the region.

Beyond delivering information to farmers spread across wide areas, mobile-based insurance systems have also emerged. Despite agriculture’s prominence, far fewer people in Africa carry agricultural insurance compared to other regions. In this context, Kenya’s Kilimo Salama launched a service that guarantees income when crops fail due to natural disasters by adding a small premium to the price of seeds at purchase. Communications are handled by SMS, and payments via M-Pesa. Because smallholder farmers can enroll, the insurance reduces the risks they face when attempting to expand, encourages investment, and helps break the vicious cycle of low income leading to low investment and back to low income.

Farmers using mobile phones, Kenya (CC BY-SA 2.0)

3. Healthcare

“Mobile health,” which leverages mobile devices to improve people’s health, is gaining attention worldwide, and Africa is no exception. Telemedicine is spreading in Ghana as well as in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Mali, connecting rural clinics to urban medical facilities via mobile phones or the internet so that people in areas with limited medical infrastructure can still access a baseline level of services. Kenya’s Maisha Meds supports management at small clinics and pharmacies in East Africa so they can provide appropriate treatments and prescriptions. Ghana’s mPedigree and similar services also allow users to verify whether drugs are genuine and not expired, reducing the risk that pharmacists or patients end up with counterfeit medicines.

Shifting to smartphones; regional gaps remain a challenge

The transformation driven by feature phones in African societies is too extensive to list, but the shift to smartphones is now steadily advancing, and internet-based services are growing across sectors. In agriculture, for example, Plantix offers more advanced support by diagnosing problems from a simple photo upload, while in healthcare the MedX eHealth Center provides an online platform for medical services.

In Africa, smartphone-based connections are expected to account for nearly 60% of all mobile connections by 2020—a 15-fold surge in just a decade—approaching the projected global average of 66% in 2020. However, as of 2017, mobile users still make up only half of Africa’s population. The growth rate of users is also slowing—from 11% in 2010–2015 to a projected 6% in 2015–2020. After taking off in more technologically advanced markets like Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa, more challenging regions risk being left behind.

Can communications in Africa continue to develop steadily? “Access to the internet is a basic human right,” argues Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who is rolling out the free internet service Free Basics to improve connectivity in Africa. However, criticism has mounted that, because access is centered on Facebook and selected sites, Facebook exercises opaque control over information. Governments have also moved to control the internet, and seeing social media as a driver of uprisings like the Arab Spring, some have even shut down mobile and internet providers before elections. Africa’s “mobile-only” communications grew in close connection with people’s lives, but as the shift to smartphones proceeds, how will a free internet environment—independent of governments and big corporations—be built? And when will everyone be able to share in its benefits?

Children playing with a smartphone (Oscar Carrascosa Martinez/Shutterstock.com)

Writer: Miho Kono

0 Comments