On June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Egypt announced the severing of ties with Qatar, claiming that “Qatar supports terrorist groups and interferes in the internal affairs of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.” Regardless of whether the suspicions against Qatar are justified, as part of the rupture these four countries banned all Qatar Airways flights from overflying their airspace. Qatar is surrounded on its south and west by Gulf states, and as of September 21, 2017, the state-owned Qatar Airways has been forced to take detour routes, including over Iran.

“Do not fly overhead—”

Cases like Qatar’s are rare, but in fact, flight restrictions are quite common in the world of aviation. The reasons vary: some are for aviation safety, while others are for national security or military purposes. Let’s unpack the “realities of the sky” that play out on the great stage above us.

Who draws the “borderlines” in the sky

A wide variety of aircraft fly in the sky. [jill111/pixabay]

The Chicago Convention lays down various principles necessary for the safe operation of aircraft, including rules on aircraft nationality and items carried in flight. Based on this convention, the UN specialized agency, the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), handles practical matters such as international coordination and recommendations.

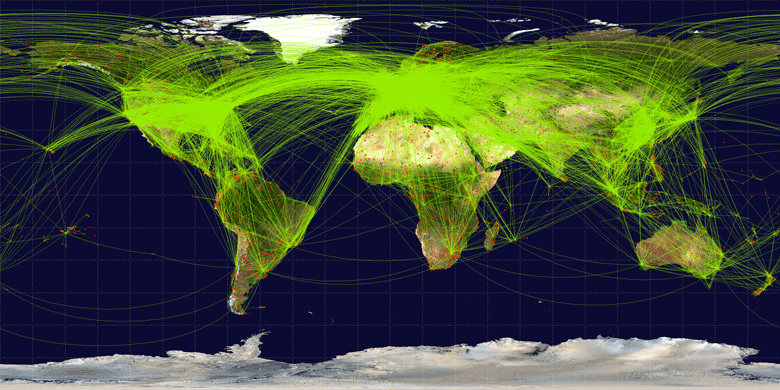

A world connected across borders by aircraft ( CC BY-SA 3.0 / World-airline-routemap-2009 by Jpatokal)

In addition, scheduled international air services cannot operate without the permission of the country whose airspace is overflown and the country of destination. Since each country has sovereignty over its territory, flying without permission constitutes an airspace violation (see note 1). These permissions are typically arranged through bilateral or multilateral “air services agreements,” on the basis of which airlines open routes.

The sky is “a place where you may not fly freely”

In aviation, the fundamental premise is that each country has sovereignty over the airspace above its own territory. Accordingly, the Chicago Convention allows countries to freely establish prohibited or restricted airspace for civil aircraft within their territory for military needs or public safety.

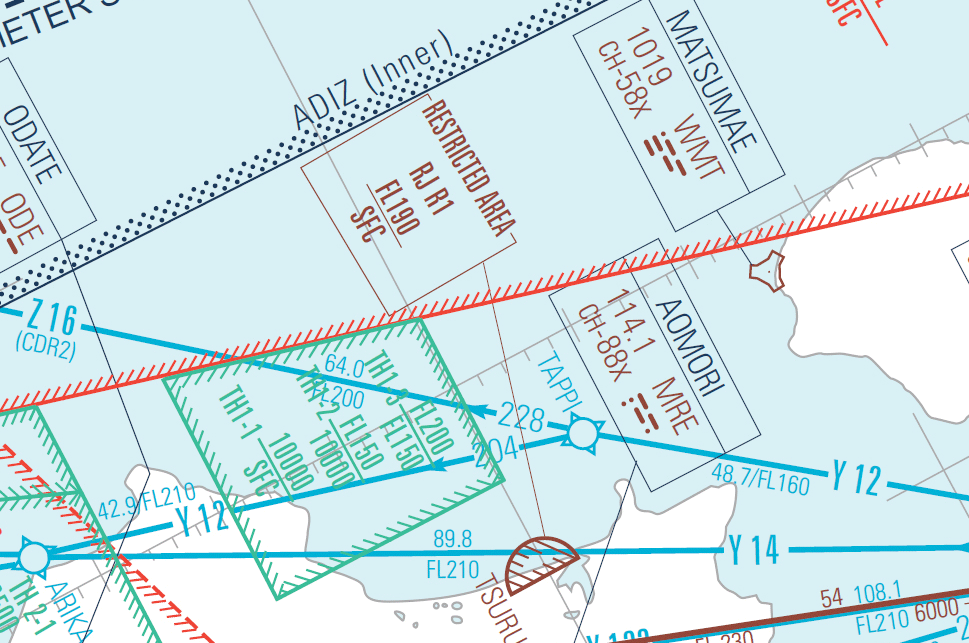

Example of restricted airspace (Japan/Aomori Prefecture) (created based on AIS Japan “ENROUTE CHART (ENRC 1)”).

Elsewhere, low-level flight is sometimes prohibited over nature reserves to prevent ecosystems from being harmed by noise or accidents, and because aircraft movements are dense around large airports, entry is prohibited without clearance from air traffic control. Furthermore, as when the Icelandic volcano erupted in 2010 and airports and airspace across Europe were closed by massive volcanic ash, flight restrictions may be imposed during disasters such as wildfires or volcanic eruptions to prevent secondary accidents and avoid hindering rescue and firefighting operations. In this way, “no-fly” areas are established for various reasons in various places.

“Places you may not fly freely” on the world map

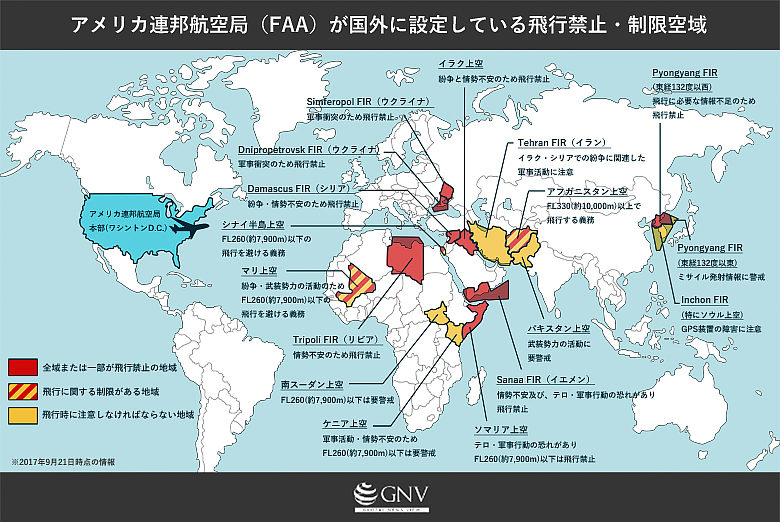

“Places you may not fly freely” are not only established domestically. In fact, a country can designate such areas over another country’s territory to restrict its own civil aircraft. Moreover, flights can be forcibly restricted within a country by external authority such as the UN Security Council. In some cases, civil aircraft are banned from entering certain regions for technical reasons as well.

Also, as occurred during the 2011 conflict in Libya, a no-fly zone may be imposed over a crisis-stricken country by the UN Security Council from outside, to halt conflict or a humanitarian crisis. Such “no-fly” zones backed by external force would violate international law and infringe sovereignty absent a Security Council resolution. For example, in the 1990s, the United States declared no-fly zones over parts of Iraq after the Gulf War and conducted airstrikes to enforce them.

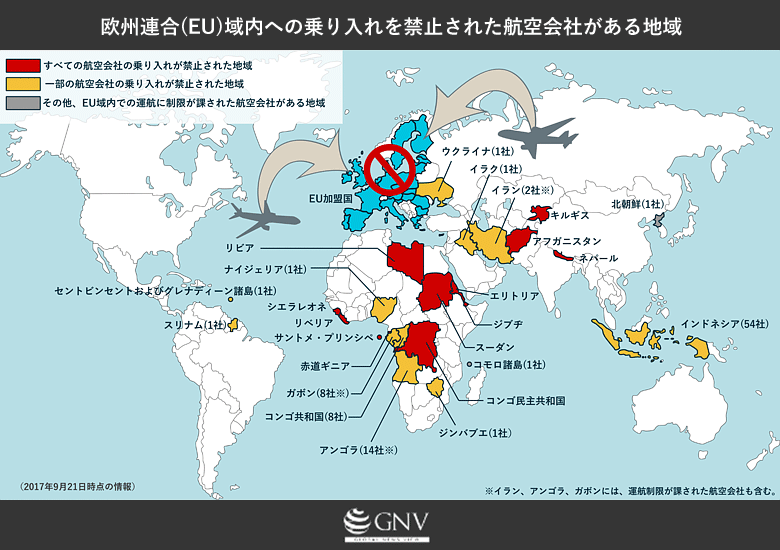

Created based on the European Commission list.

Therefore, when there are technical shortfalls in maintenance and inspection, or when regulatory oversight is immature, airlines may be prohibited from entering certain regions for safety reasons. For example, as shown in the figure, the European Union (EU) bans carriers with technical safety concerns from operating into EU airspace to safeguard its safety. Conversely, operations may still be possible for airlines on the list if they are leased and flown using aircraft and crews from non-banned carriers, but this also seems to symbolize the “North–South” relationship in the aviation world.

“Tolls” in the sky

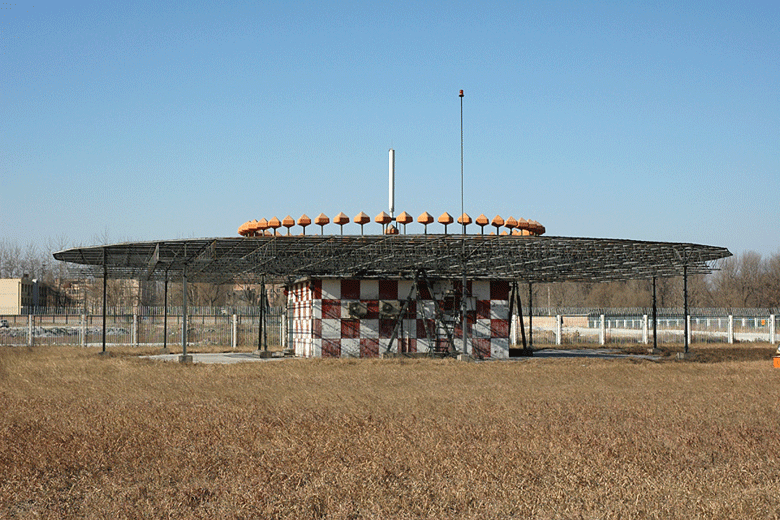

Aircraft need various kinds of support from the ground to fly. Controllers who manage traffic from the ground are indispensable for safe flight, and even in the GPS era, ground-based radio navigation facilities guide aircraft around the world. For air traffic control, countries share responsibilities for providing necessary flight information and search-and-rescue within regions called Flight Information Regions (FIRs) established by ICAO.

Example of a ground-based navigation aid: VOR / DME (CC BY-SA 2.0 / by Yaoleilei)

As for these “overflight fees,” for example, the United States, which controls vast FIRs over the Pacific, in 2017 charged $58.45 (about ¥6,400) for every 100 nautical miles (about 185 km) flown along airways. According to the industry group of the world’s airlines, the IATA (International Air Transport Association), airlines pay a total of more than $25 billion (about ¥2.7 trillion) annually to countries worldwide. Considering the safety of the skies, the costs of maintaining air traffic control and ground navigation facilities and their staffing cannot be taken lightly, but some point out that this revenue may be one reason governments are reluctant to close airspace even when conflicts make flying dangerous.

How are flight routes determined?

Airlines usually choose the most economical route with the least fuel consumption based on operational information such as “places you may not fly freely” and the day’s weather forecast. Of course, airlines cannot fly through prohibited airspace, and considering the possibility of an emergency descent or landing due to malfunctions, “places you may not fly freely” can pose risks even when nearby rather than directly overhead. However, the degree to which airspace-related risks are prioritized is ultimately up to each airline’s judgment.

For example, on July 17, 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight 17 from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down over Ukraine. The day after the crash, Ukrainian authorities closed the entire eastern sector to flight, but at the time of the shootdown, flight above FL320 (about 9,800 m) was considered safe, and, with a few exceptions, many airlines were flying routes across Ukrainian airspace. Whether the route your aircraft takes is safe is, in reality, entrusted to your airline’s business judgment.

From above, there are no borders in sight

[april_kim/pixabay]

Humanity invented the airplane and first flew in 1903. In just over a hundred years, we’ve literally come to fly all over the world. Carrying hundreds of lives and cargo, silver wings soar into the distant sky. Yet this romantic world of aviation mirrors the ground below, reflecting diplomatic conflicts, regional situations, and technological disparities. Unfortunately, aircraft crisscrossing the globe are not free to roam the skies like migratory birds.

[Footnotes]

※1: Non-scheduled flights not operated as transport services can basically overfly or make a technical landing without prior permission, as long as they comply with landing requirements of the state concerned.

※2: FL (flight level): A unit of flight altitude commonly used at high altitudes to avoid collisions during cruise by aircraft that measure altitude using atmospheric pressure. FL100 = approx. 10,000 ft (about 3,050 m).

Writer: Yosuke Tomino

Graphics: Yosuke Tomino

0 Comments