On June 12, 2014, the World Cup kicked off in Brazil. The once-every-four-years, world-class sporting festival swept the globe into a frenzy. In Japan, it was prominently reported day after day, and the country was swept up in World Cup fever—a recent memory. Judging from the match results and the social excitement surrounding them, many people likely believe that hosting the World Cup (hereafter, WC) brings positive effects to the host country.

Spectators in a frenzy at the Brazil World Cup Photo: Agência Brasil (CC BY 3.0 BR)

However, behind the lively, glamorous World Cup, Brazilian society was grappling with many social problems. What specific issues did it face? And how much did the Japanese media highlight and cover them? Let’s take a closer look.

Social issues behind the Brazil World Cup

In recent years, Brazil has achieved remarkable economic growth, rising to become the world’s sixth-largest economy. At the same time, however, household income among the poor has declined, the wealth gap has remained unbridged, and many Brazilians still live in poverty today.

Across Brazil, there are many slums known as “favelas.” In the run-up to the World Cup, under the banner of “social cleansing,” the Brazilian government forcibly evicted more than 15,000 families from favelas alone, pushing residents to the outskirts of cities. The government claimed these actions were necessary to modernize urban areas, followed due process, and that residents were not forcibly relocated. In reality, however, it was clear that the purpose of the evictions was to secure land for stadium construction and infrastructure development for the World Cup. Civil society groups testified that those forced to leave did not receive adequate compensation and were often given little to no prior notice (according to their accounts).

A view of a favela Photo: chensiyuan (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Beyond forced relocations, other issues that affected a larger portion of the population emerged, culminating in protests against the World Cup. Violent confrontations between police and demonstrators often escalated, with tear gas and rubber bullets used. Dissatisfaction with how tax money was being spent prompted demonstrators to protest against the government. Hosting the World Cup requires massive funding for stadium construction and infrastructure. Meanwhile, Brazil still had a large wealth gap, and its education and healthcare systems could hardly be called robust. In that context, the government’s attempt to prioritize a large portion of tax revenue for the World Cup rather than for education and healthcare triggered public backlash.

Many citizens were also dissatisfied with working conditions, staging strikes to demand improvements and often marching in protest alongside demonstrations over tax spending. Just before the World Cup, the harsh working conditions for laborers engaged in World Cup-related jobs, such as stadium construction, came to light. Poor migrants and others were forced to work under grueling conditions for extremely low wages, almost like slaves. Beyond these issues, corruption and public security were also major concerns.

“We are not against football” “Money for education” Photo: Agência Brasil (CC BY 3.0 BR)

Trends in Japanese media coverage

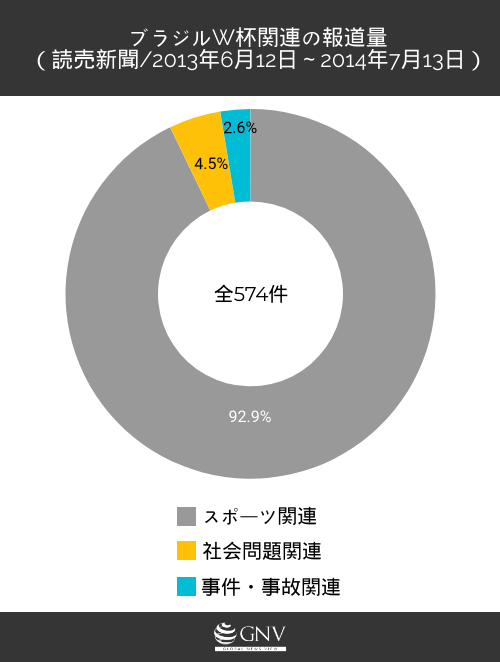

We have seen the many social problems Brazilian society faced in the shadow of the World Cup, but how much did the Japanese media cover these realities? Take a look at the following figure.

This is an analysis of the volume of coverage related to the Brazil World Cup in the Yomiuri Shimbun. From one year before the tournament until its conclusion, there were 574 articles related to the Brazil World Cup (Note 1). The vast majority reported match results and offered commentary. Articles about Japan’s national team were particularly prominent. By contrast, only 26 articles primarily focused on Brazil’s social issues, a mere 4.5% of the 574. Meanwhile, the number of articles primarily covering the Brazilian national team (31) exceeded those on social issues. There were also 15 articles (2.6%) about incidents and accidents such as riots by supporters.

What exactly did the 26 articles on social issues—the small minority—cover? The figure below shows a breakdown of those issues (Note 2).

As the figure shows, among the social issues covered, the most frequent topic was public opposition to how tax money was being spent. The second most common topic was working conditions. Moreover, 16 of the 26 articles focused on demonstrations that arose from these issues.

Social problems lurking in upcoming World Cups

The social problems that accompany hosting the World Cup are not limited to Brazil. The World Cup is set to be held in Russia in 2018 and in Qatar in 2022. In both of these upcoming host countries, related social issues have already begun to surface.

In Russia, it came to light that laborers working on World Cup construction sites were left unpaid, worked in dangerously cold conditions, and faced retaliation for raising concerns. There were also reports that 17 workers died during stadium construction, making it clear that exploitation and abuse of workers were rampant. Similarly in Qatar, dozens of Nepali migrant workers who came to build stadiums died within a matter of weeks, and thousands have been found to be enduring labor abuses. Reports include cases of being made to work 12 hours while hungry, being forced to work long hours in temperatures up to 50°C (122°F) without being provided drinking water, and withholding wages to prevent workers from fleeing—an utterly horrific working environment.

A stadium under construction in Qatar Photo: jbdodane (CC BY-NC 2.0)

There is also a strong possibility that bribes played a role in the decisions to award the tournaments to Russia and Qatar. Three FIFA executives appear to have accepted bribes prior to the final decisions on the 2018 and 2022 hosts.

Amid various bribery allegations, FIFA released a report summarizing the details, which laid bare an extremely questionable voting system. Russia and Qatar, however, continue to deny wrongdoing. If definitive evidence of bribery is found, there is a high possibility they will be stripped of hosting rights, but as of now there has been no decision to change hosts, and the bribery allegations remain shrouded in darkness.

Thus, far from being limited to Brazil, a variety of problems arise in host countries when the World Cup is held. While FIFA has at times taken countermeasures against these issues, it is hard to say they are fully effective; if anything, it can seem as though the organizers are being co-opted by host nations.

While the World Cup captivates and excites viewers, it is also an event that requires enormous funding and exerts a major impact on the host country’s society. The same is true of the Olympics: although host countries tend to tout the positive economic effects of hosting, in most cases the overall outcome is a net loss, according to reports. Brazil is no exception. Moreover, not all citizens benefit from the World Cup; we must not forget that there are social problems in the background and people who are suffering.

In a Japanese media environment where the major social issues behind such events are scarcely reported, it is essential that we not be confined to what is reported but instead view the world more objectively. How will the World Cup be covered in Japan going forward? We will continue to watch trends in the Japanese media.

A Brazilian boy kicking a ball in a favela Photo: Axel Warnstedt (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Note 1: Using “Yomiuri Shimbun Yomidashi Rekishikan,” we counted Tokyo morning edition articles whose headlines included either “W杯,” “ワールドカップ,” or “ブラジル.” World Cups in sports other than soccer, as well as beach soccer and futsal, were excluded from the count.

Note 2: For topics listed in the legend, if multiple topics were mentioned in a single article, each mention was counted.

Writer: Yutaro Yamazaki

Graphics: Yutaro Yamazaki

0 Comments