In February 2017, Jürgen Mossack and Ramón Fonseca, the principals of the Panamanian law firm “Mossack Fonseca,” in connection with Brazil’s corruption scandal on suspicion of money laundering were arrested. This law firm was one of the parties implicated in the documents made public worldwide in April 2016 by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), known as the “Panama Papers.” Immediately after the release, the papers became a global topic, and the resignation of Iceland’s prime minister and suspicions involving Russia’s President Putin were among the various developments seen around the world. However, a year on, progress has slowed, and the arrest of the firm’s two top figures is the first major news related to the Panama Papers in quite some time.

To explain the Panama Papers once again: they are an enormous cache—2.6 terabytes—of confidential documents created at the law firm Mossack Fonseca concerning financial transactions that used tax havens. Contrary to a common misunderstanding, a tax haven does not mean tax evasion; it refers to regions or countries where tax rates are extremely low or zero. In such jurisdictions, not only are taxes low, but the anonymity and secrecy of companies and individuals conducting transactions there are strictly protected by law. Many of the world’s tax havens are British overseas territories, and today, the top five tax havens are said to be Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Singapore.

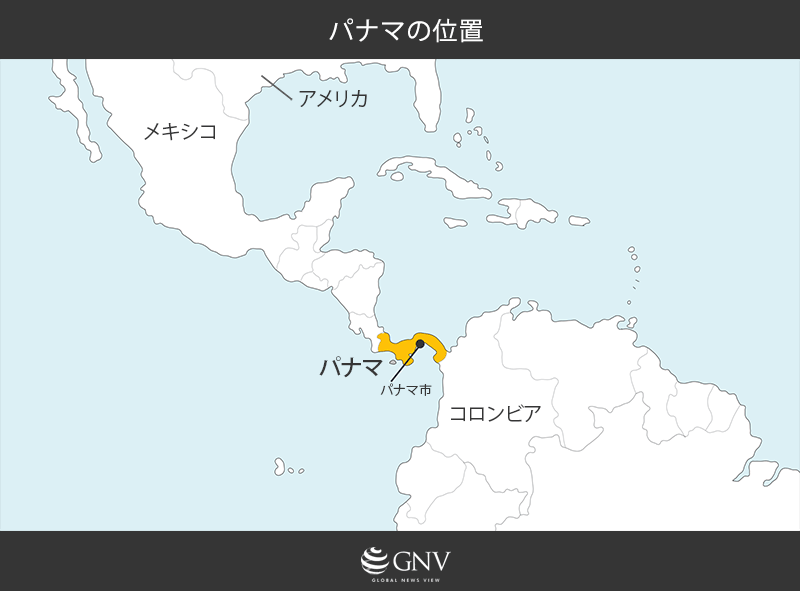

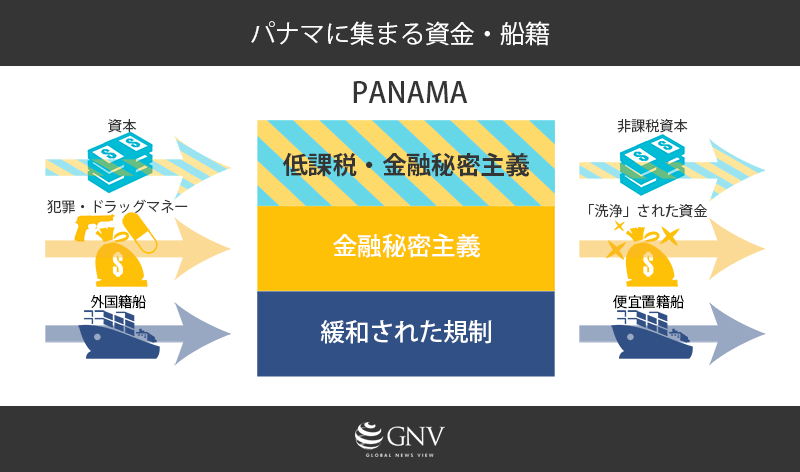

When the documents were released, the Panamanian government criticized it. Their claim was that the matter concerned the law firm Mossack Fonseca and its clients, not Panama or the Panamanian government. Indeed, involvement by companies and individuals from around the world for improper purposes was confirmed. However, Panama’s status as a tax haven is built on national policies—its tax system and financial secrecy regime—and the Panamanian government is in a position that encourages the use of tax havens. Moreover, Fonseca is also an adviser to Panama’s president and a close friend.

Night view of Panama City Photo: BORIS G/flickr [CC BY 2.0]

What, fundamentally, is the problem with tax havens? Tax avoidance using tax havens can be illegal in some cases and legal in others. Either way, when individuals and companies use tax havens, the states to which they belong lose tax revenues they would otherwise receive. An estimated 50% of global trade is routed through tax havens, and enormous sums are “saved” in taxes. This is a painful loss for any country, but in developing nations the situation is even more serious. Through trade misinvoicing, they lose tax revenues they should receive, are deprived of funds to develop, and the wealth gap with advanced countries widens. As weaker players in the global economy, it is difficult for them to take effective countermeasures.

Because financial regulations are extremely lax while secrecy rules are strict, Panama is also a major hub for money laundering. By routing funds through tax havens, the flow of money can be made opaque—and ultimately anonymized—making it impossible to trace the source. Even if the funds were obtained through criminal activity, once laundered they become untraceable. In Panama, this has been used by criminal organizations in countries such as Colombia and Mexico, with proceeds from illegal activities such as drug trafficking, fraud, and human trafficking converted into “clean money” that funds those organizations. Drug money, in particular, is a serious problem.

Nor do the problems caused by Panama’s lax regulatory standards and low taxes end there. Flags of convenience carry similar risks. In principle, a ship should be registered in the country where it is operated, but to avoid taxes and regulations, it is not uncommon to create shell companies in other countries solely to own the vessel, placing the ship’s registry in a country different from the owner’s home country. Panama has the most flags-of-convenience ships in the world, and together with Liberia and the Marshall Islands, which follow, 60% of the world’s ship registries are held by these three countries. To attract flags of convenience, these countries deliberately set looser labor and safety standards compared to others, and many vessels lack adequate working conditions and safety measures. Moreover, exploiting weak oversight, a range of criminal activities—such as transporting drugs and weapons and illegal fishing—are carried out using flags-of-convenience ships, which is also a serious problem.

Panama’s development into such a state stems from its path to independence. In 1903, Panama achieved independence from Colombia under strong U.S. influence. The new constitution included provisions recognizing U.S. sovereignty in the Panama Canal Zone, effectively placing the country in a protectorate-like position. Its role as a tax haven dates from 1919 in this era under U.S. protection. It is said to have begun when Standard Oil, a major U.S. oil company, registered ships in Panama to avoid U.S. taxes and regulations. Other companies followed suit, placing flags of convenience in Panama, and under continued U.S. influence, Panama built out its tax-haven system.

The 1989 invasion of Panama is also indispensable to this story. Manuel Noriega, commander of the Panamanian Defense Forces, became the country’s dictator in 1983 and had connections with drug cartels. The United States tolerated this, and during that time Noriega established Panama’s money-laundering business. In fact, he was on the CIA’s payroll as a useful figure supporting U.S. policies—including illegal activities—in Latin America. But after Noriega fell out with the United States, the invasion began and he was ousted under the pretext of drug trafficking. In 1999, the Panama Canal was returned by the United States, and Panama ceased to be a “protectorate,” but its ties with the U.S. remain deep. Analysis of the Panama Papers found that companies headquartered in the United States were not necessarily the most numerous among those using Mossack Fonseca, but it is also the case that, in terms of the number of companies with subsidiaries or affiliates in Panama, the largest share is American.

Despite the many serious problems Panama faces, the government shows little eagerness to pursue solutions. For example, after the Panama Papers were released, the Panamanian government set up a commission to investigate, but it ultimately failed to function properly. Seven members, including Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, served on the commission and prepared a report. However, despite once promising to publish the findings, the Panamanian government refused to make the report public. In response, Stiglitz and fellow member Mark Pieth resigned and produced and published their own report. Meanwhile, doing little toward a resolution, after the documents were released the Panamanian government began paying a public relations firm $50,000 per month, seeking to improve the country’s image—to dispel the negative perception created by the “Panama Papers.”

Panama has become a hub for many forms of crime and exploitation, yet the government takes a stance of maintaining the status quo. This is because the government and elites profit from the current system, and reform would be inconvenient for them. The issue is also deeply connected to the global financial system. The Panama Papers brought this problem to public attention, but it will require continued scrutiny.

Scattered banknotes (goldyg/shutterstock.com)

Writer: Mai Ishikawa

Graphics: Mai Ishikawa

0 Comments