In recent years, the number of refugees has continued to rise, and the world is facing the largest refugee crisis since WWII. The total stands at 63.5 million; of these, 20 million (2015 UNHCR) are refugees who have fled abroad, while the remainder are still displaced within their own countries. Refugees are overflowing especially in Middle Eastern countries and an urgent solution is needed, but the ripple effects have reached the distant Pacific as well, creating refugee issues there. On the small Pacific island nation of the Republic of Nauru and on Manus Island in the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, refugees who have fled their homelands aiming for Australia are being held in regional processing centers on the islands under the pretext of “awaiting refugee status determination,” and are treated as if they were prisoners. Their living conditions are extremely poor, and abuse and sexual violence by local residents and facility staff are rampant. This situation is being deliberately left unaddressed by the Australian government.

The Republic of Nauru (hereinafter “Nauru”) and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea (hereinafter “Papua New Guinea”) are relatively weak economically. This economic situation is tied to Australia’s offshore processing policy for refugees. In exchange for temporarily accepting refugees, the two countries receive large amounts of economic aid from Australia. In Nauru’s case, because the country is experiencing a severe economic collapse, it is no exaggeration to say that it depends on this aid. Specifically, 15% of Nauru’s national revenue in 2014–2015 came from Australian ODA. Separately, Australia bears all policy-related costs such as facility operating expenses and transfer costs for refugees in the two countries. Including other refugee deterrence policy costs, the amount is said to have reached USD 7.3 billion between 2013 and 2016.

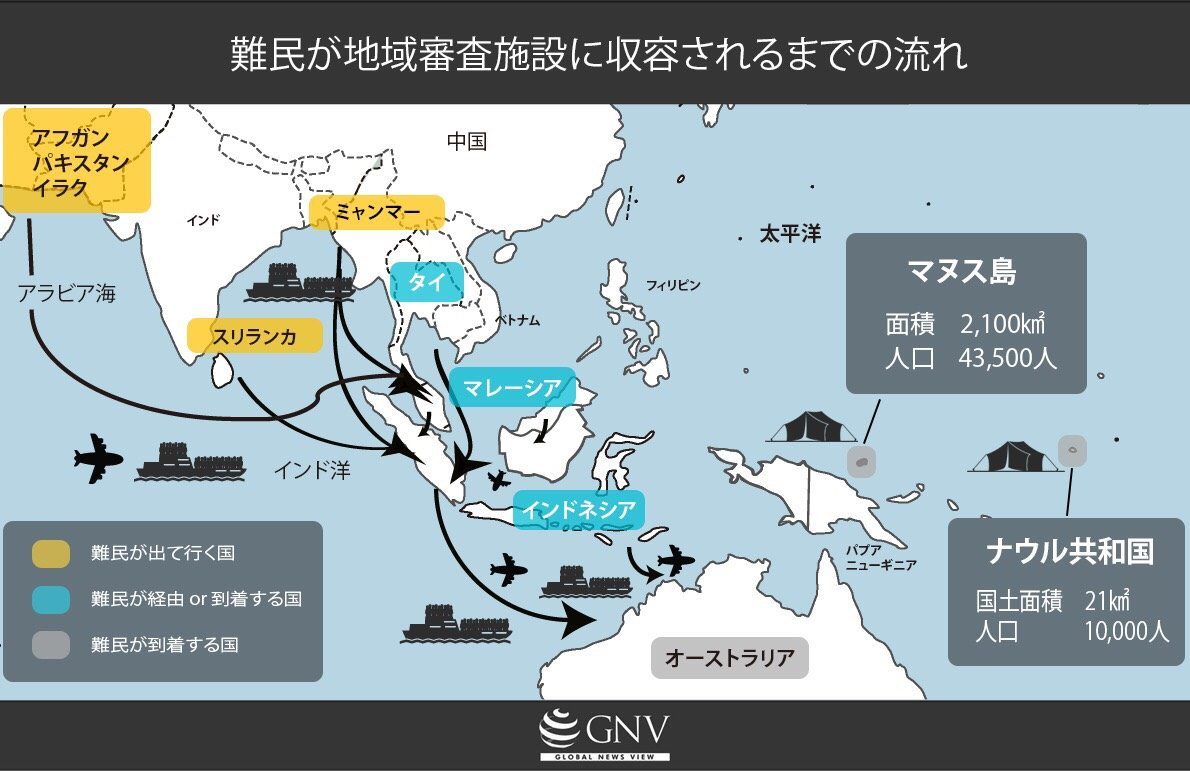

Currently, on Nauru and Manus Island, people who have fled from the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and elsewhere are living inside and outside the regional processing facilities. They attempt to enter Australia by sea via Indonesia and other routes. As a preventive measure, the Australian government has strengthened military presence on the northern coast and turns refugees back to Indonesia. For those who have once entered Australian territorial waters, as noted above, under the guise of refugee status determination they are returned to Nauru or Manus Island. This is based on the idea that until refugee recognition is completed, they are not necessarily refugees. However, there is a study showing that of those who arrived in 2011–2012, over 93% were not so-called “economic migrants” seeking a higher standard of living, but were in fact refugees. As of August 31, 2016, 410 people on Nauru and 823 on Manus Island were detained inside the centers, and their ability to go outside is severely restricted. In addition, on Nauru, 749 people who have been recognized as refugees live outside the facilities.

Flow until refugees are confined in regional processing facilities Created based on data from Human Rights Watch

For many years, entry to these islands was strictly controlled by the Australian government, and conditions on the islands rarely came to light. However, recently, undercover investigations by Amnesty International (NGO) and whistleblowing by former facility workers have revealed the reality.

The conditions faced by the refugees are extremely harsh. Investigations on Nauru found that they live in plastic tents; in heat exceeding 40°C, there is no adequate air conditioning. They can secure almost no privacy. Sanitation is poor, and infectious diseases such as skin conditions and malaria are rampant. On Manus Island, it has been reported that almost all of the approximately 40 children living inside the center have tuberculosis. Yet they can hardly receive medical care. Beyond shortages of medicines, even illnesses that are relatively easy to treat are sometimes deliberately delayed or refused treatment. As a result, a death occurred on Manus Island in August 2014: a 24-year-old man with a mild skin infection eventually developed sepsis and died.

Facility where refugees live (Nauru)

By DIAC images CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

There are also allegations that in the regional processing facilities, crimes are commonplace, including violence, abuse, sexual offenses, and looting by local residents and authorities. However, when local residents commit these acts against refugees, they are rarely held criminally accountable. Meanwhile, refugees themselves are sometimes arrested on fabricated evidence. On Manus Island in May 2014, a 23-year-old man lost his life after being assaulted by Papua New Guinean guards during a riot at the center. On Nauru, there were 20 recorded rapes of women in 2015 alone. Amid the rampant crime and dire living environments on the two islands, people struggle with uncertainty about the future. Yet they are not provided adequate mental health care, and incidents of self-harm and suicide attempts are unending. Although the governments of the countries involved are aware of these facts, they are leaving and condoning them. Behind this lies the government’s intention to prevent refugees from settling in Australia. The policies are carried out with the aim of making refugees who can no longer endure the current situation volunteer to return to their homelands, or to deter them from attempting to reach Australia in the first place.

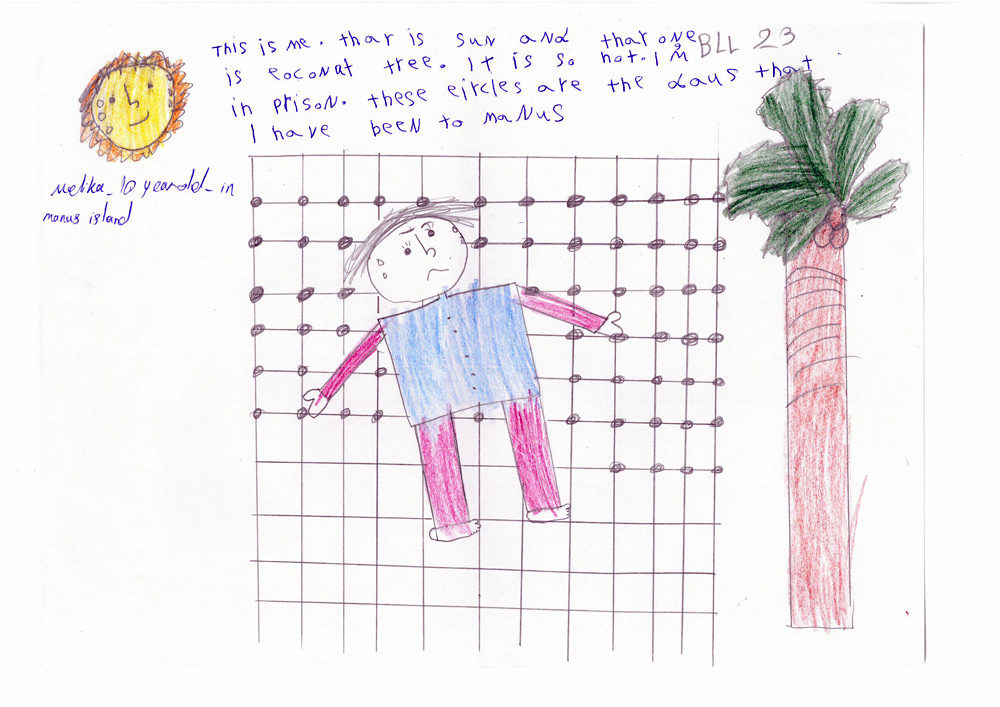

Drawing by a 10-year-old child living in the facility (Manus Island)

“It’s very hot. I’m in prison. These circles are the days since I came to Manus.” (excerpt from the text in the picture)

By Greens MPs /Flicker CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When refugees head to Australia by sea, they often rely on people smugglers and sail the open ocean with boats that are far over capacity. Boats sometimes sink or capsize, resulting in deaths; it is a journey that risks their lives. To curb the increase in arrivals and the resulting string of deaths at sea, Australia created an offshore processing policy known as the “Pacific Solution,” under which refugee status determination is conducted “carefully” in third countries near Australia. It was actually launched in 2001 but was abolished in 2007 by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. However, after the end of the Pacific Solution, the number of refugees arriving in Australia by sea increased again, and criticism was directed at both the smugglers and the Australian government. In response, in 2012 the government reinstated the policy. It is estimated that at least 1,991 people died during sea crossings between January 2000 and January 2017.

Refugees who arrived by boat from Sri Lanka By Mike Prince / Flicker CC BY 2.0

However, due to growing criticism at home and abroad following revelations of the shocking reality, and pressure from NGOs, this policy is now on the verge of being abolished. In Papua New Guinea, on April 26, 2016, the Supreme Court ruled that the refugee detention facility was illegal and ordered its closure. Yet neither Papua New Guinea nor Nauru, due to poverty, can afford to accept the refugees. Transfers to Cambodia, the Philippines, and Kyrgyzstan were considered and even attempted in some cases, but none succeeded. The alternative proposed by the Australian government was to transfer them to other developed countries. The United States reached an agreement to recognize 1,600 of 2,400 refugees since 2013 and resettle them. However, this was an agreement under the Obama administration, and President Trump, an anti-immigration hardliner, stated on Twitter that it was a “dumb deal” (as of 2017.2.2). It is necessary to watch future developments, including the possibility that the deal will be scrapped. Moreover, it is only a one-time agreement; the Australian government is considering a lifetime ban on visas for refugees who arrive by boat in the future. For refugees whose resettlement is denied and who then refuse to return to their home countries, Australia is negotiating a 20-year visa with Nauru. In short, while the facility on Manus Island is expected to be closed, the one on Nauru is likely to remain.

Demonstration calling for the closure of regional processing facilities (Melbourne) By Takver / Flicker CC BY-SA 2.0

While the existence of people smugglers is certainly a problem, refugees are often left with no choice but to rely on them. If those refugees are subjected to inhumane treatment even in places of refuge, the refugee crisis will never move toward resolution. But is this a problem limited to the Australian government? A study found that “the five richest countries in the world host less than 5% of all refugees.” The United States, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Germany together hold half of the world’s wealth. Meanwhile, the combined number of refugees hosted by Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Pakistan, and Palestine amounts to half of all refugees. In addition, 86% of refugees who have fled abroad are in developing countries. Many developed countries, including Australia, refuse to accept refugees on the grounds of economic burden. This stance is one reason for the current imbalance in refugee hosting. Are refugees really nothing but an economic burden? Amid this humanitarian crisis, it may be necessary for the entire world to address this issue together.

Writer: Mizuki Nakai

Graphics: Aki Horino

0 Comments